Brett Rogers, Director of The Photographer’s Gallery

The Photographers’ Gallery is celebrating its 50th anniversary looking back at the shows that shaped it. Here, in the final part of the series, director Brett Rogers talks us through the highlights of the 2000s and the 2010s

2000s

“By the time I joined The Photographers’ Gallery as director in December 2005 – a period which coincided with two great shows at the gallery: Isa Genzken: Der Spiegel 1989-1991 (2005) and Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel: Evidence Revisited (2005) – I was able to build on my previous experience of co-curating Reality Check: Recent Developments in British Photography and Video (2002) with Kate Bush,” says Brett Rogers, who remains the director today. “It gave me a unique insight into how the gallery operated and some of the constraints it faced.

“As a ‘punter’ I had long appreciated the diversity and breadth of the gallery’s programme and was always surprised to go and see something I was particularly drawn to, only to discover that the other shows were just as, or even more, interesting,” she says. “To this day, this is something I love to hear. When our visitors tell me: ‘I came in to see ‘so and so’ as I knew and loved their work, but actually the other show was even more of a revelation to me’.”

“As it explored London’s vibrant and bohemian scene in the mid 1960s, I saw this as an opportunity to open the programme up to broader cultural audiences – those interested in film, fashion, popular culture and archives, and to grow our own core photography audience.”

To celebrate The Photographers’ Gallery’s 50th anniversary this year, Rogers and her team have been sifting through the archives to select 50 Exhibitions for 50 Years – a collection of the most significant moments representing both the history of the gallery and the history of the medium too. Here, she ruminates on the 2000s, and shares some of her most notable memories from the period.

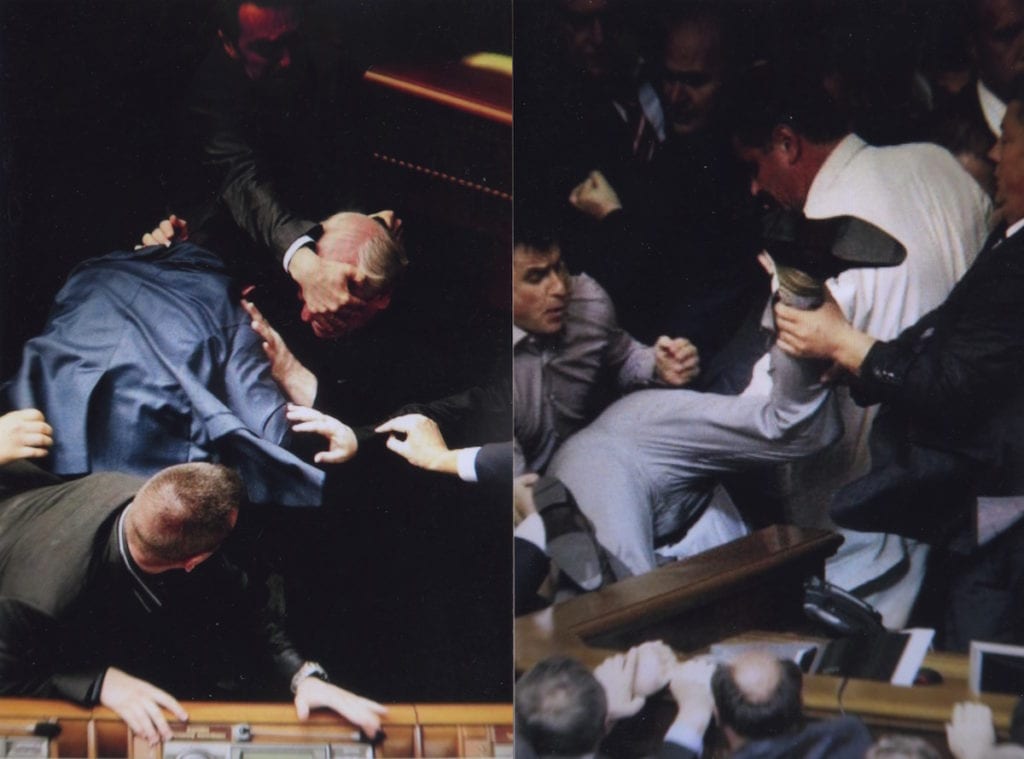

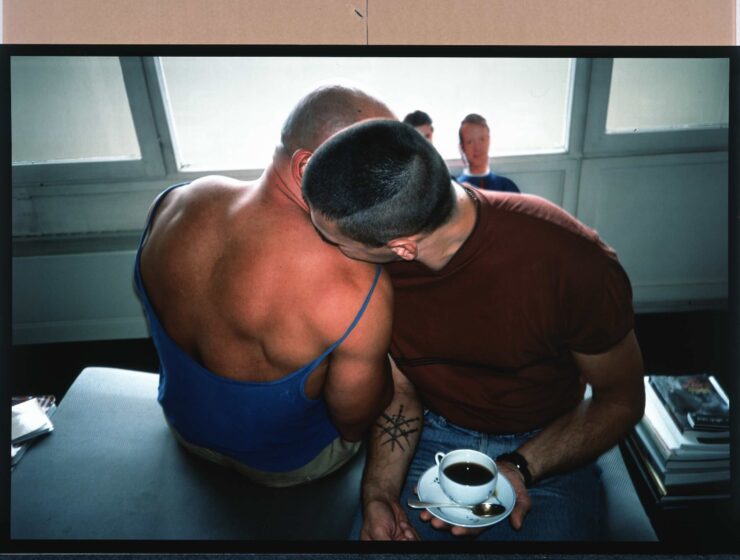

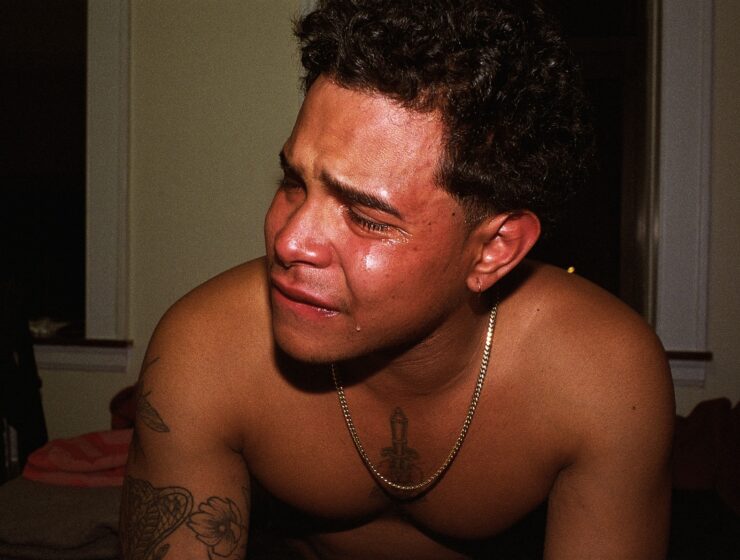

One of the ways that Rogers traced notable developments in photography during this period is the annual Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize. “I think the DBPFP shortlisted photographers each year of this decade truly reflect the way in which the medium was moving,” she explains, “from Boris Mikhailov’s ‘collaborative portraits’ in Ukraine (2001) and Juergen Teller’s bold installation merging fashion and personal imagery (2002). A little later in the decade the more direct political engagement with history (and the archive) was reflected in Walid Raad’s (The Atlas Group, 2007) work, as well as Robert Adams’ (2006) more classical documentary approach to addressing issues of ecological damage and the legacy of [American] history.”

The first season for which Rogers was ‘artistically’ responsible was in summer 2006. Under her direction, the gallery presented an archival show of prints selected from the London Fire Brigade Archive (2006). Alongside this, Antonioni’s Blow-Up – London 1966: A photographer, a woman, a mystery (2006) was shown too – an exhibition curated by Philippe Garner and David Allan Mellor that took its cue from one of the most iconic 60s movies. “As it explored London’s vibrant and bohemian scene in the mid 1960s, I saw this as an opportunity to open the programme up to broader cultural audiences – those interested in film, fashion, popular culture and archives, and to grow our own core photography audience,” says Rogers. “The Fire Brigade show exceeded all expectations, appealing to a very diverse audience, including the contemporary art community.”

Alongside its wide-ranging exploration of genres and subcultures, the programme of the 2000s also paid attention to communities across the world, and through shows including Stories from Russia: The David King Collection (2005) and Once more with feeling: Recent Photography from Colombia (2008), it brought an expansive constellation of stories and lived existences into focus.

2010s

From landmark shows to boundary-breaking moments in photography’s history, The Photographers’ Gallery has been a witness and a catalyst to many significant advancements of the medium across the years. There are just five shows selected from this final of five decades – compared to 15 from the 1980s – making it the most succinct collection of them all. The shows included are Double Take: Drawing and Photography (2016), which continued the gallery’s interdisciplinary thread; Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s: Works from the Verbund Collection (2017); All I Know Is What’s On The Internet (2018-2019); and two solo shows, The Family and the Land: Sally Mann (2010), and Edward Burtynsky: Oil (2012).

Explaining her choices, Rogers says, “We chose Sally Mann because I wanted to address the issue of why her work had never been shown in the UK. There had been controversy surrounding her early family work, but I had also recently seen compelling new work she had produced using the wet collodion process. Portraits of her then-teenage children who had appeared in the early images (as youngsters) but were now completely transformed (once again) through Sally’s innovative approach to the photographic medium.” Rogers was also impressed by a new series Mann was developing, relating to the shadow of American colonial history, set in the American South where Mann lived. “I imagined that a show which combined The Family and the Land would provide the right context in which to reappraise her early work, and demonstrate the continuity of her interest in portraiture while introducing the newer landscape series to a British audience for the first time.”

Another critically important show from this decade was All I Know Is What’s On The Internet, which demonstrated the problem of understanding how photography has been transformed in the age of social media. “Over the past decade, visual knowledge and ‘authenticity’ have become inextricably linked to an attention economy, subject to the largely invisible actions of bots, crowd-sourced workers, western tech companies and ‘intelligent‘ machines,” says Rogers. “This exhibition [presenting the work of 11 artists/collectives] sought to map, visualise and question the cultural dynamics of 21st century image culture. As part of the gallery’s pioneering Digital Programme, and as the first photography gallery to appoint a curator of digital programming, in 2011, it was a radical exploration of photography within a networked culture.”

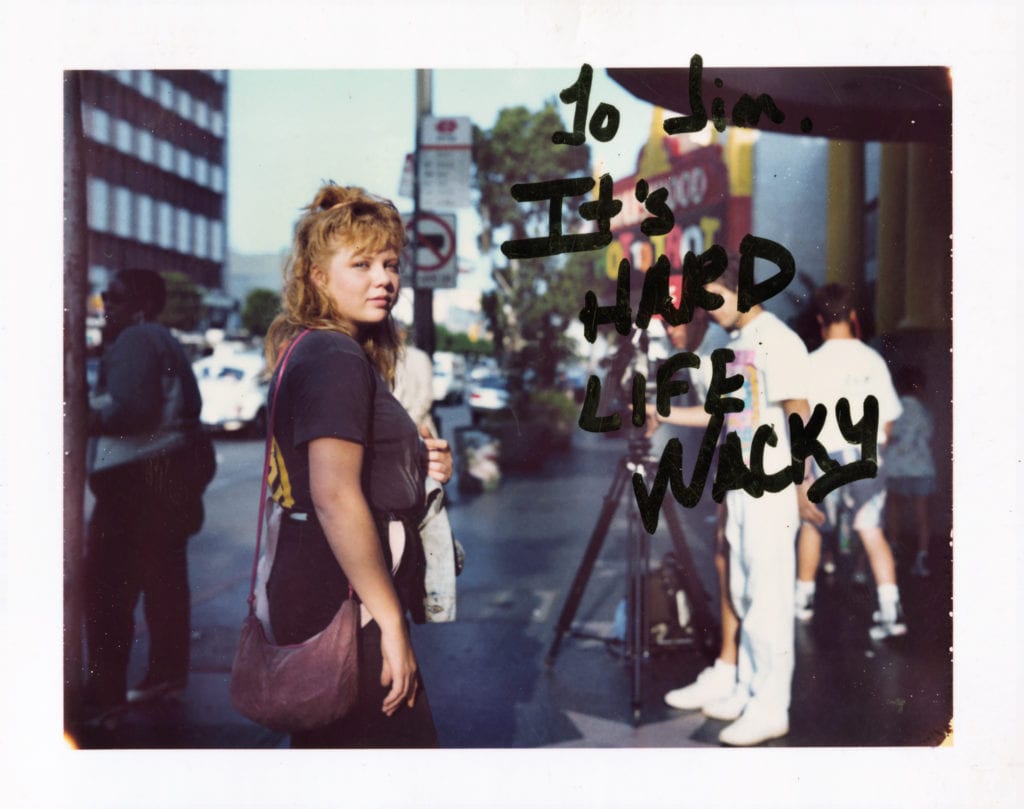

Rogers’ final thoughts about this decade land once again on the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, which is hosted at the gallery once a year and represents some of the most exciting engagements with the medium by artists across the world. Chinese conceptual artist, Cao Fei, was this year’s winner. From the expanded documentary work of Jim Goldberg towards the beginning of the 2010s, to Susan Meiselas at the end of it, there was a “distinct narrative trajectory”, Rogers says. Looking back through the winners helps to trace how issues of agency and power came to the fore.

thephotographersgallery.org.uk/

To find out more about the previous decades, head to Brett Rogers musing about the 70s, 80s and 90s.

You can also read our exclusive interview in the new Activism & Protest issue of BJP with curator David Brittain, who is responsible for the Light Years exhibition. The show runs until February 2022