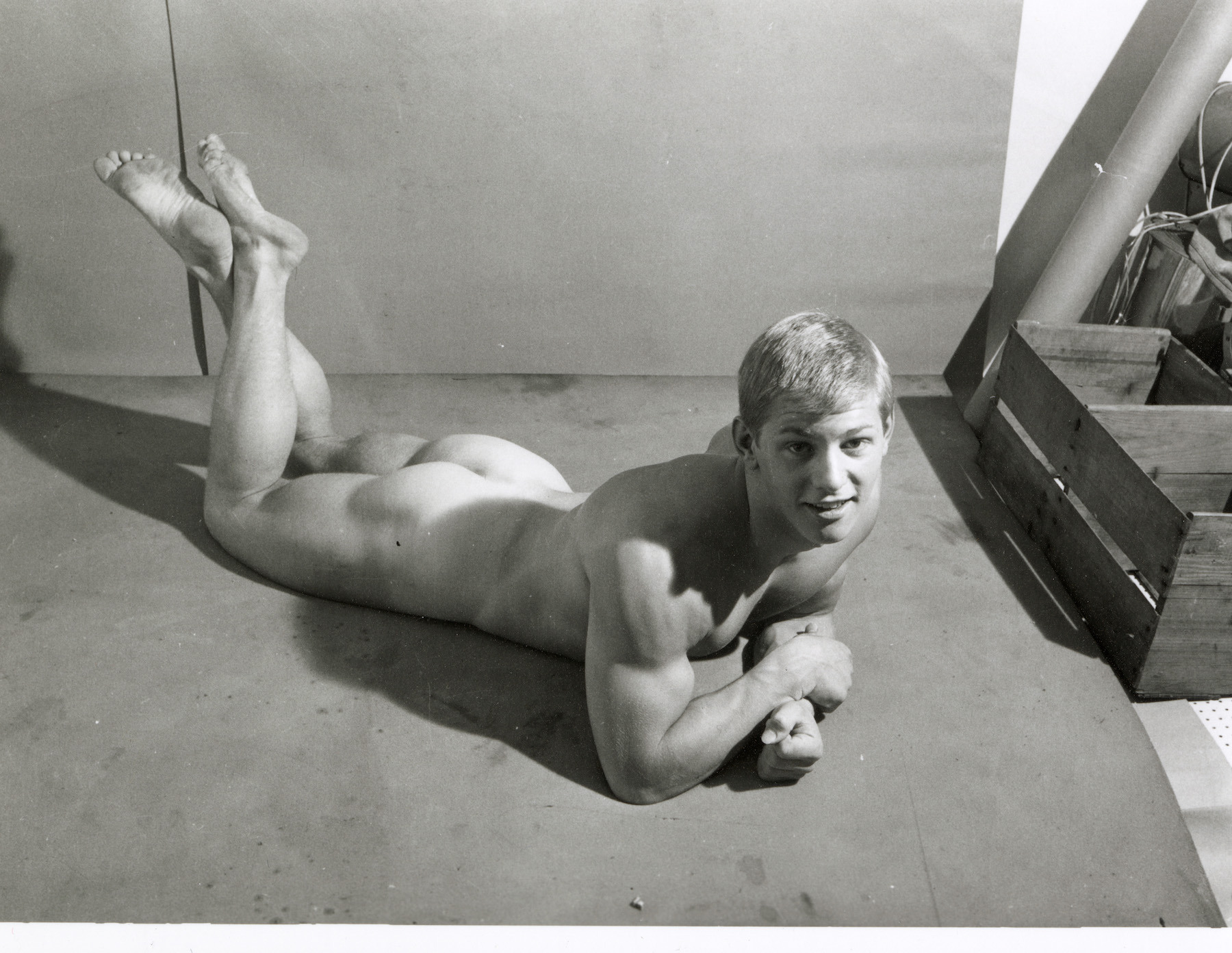

John S Barrington, John Hamill, circa 1966. Courtesy Rupert Smith Collection

A new exhibition at The Photographers’ Gallery traces the origins of gay physique photography in the capital, from Chelsea Barracks to Highgate Pond

Before there was Grindr, the hookup app used predominantly by gay and bisexual men, there was cruising – the search for an encounter that could lead to sex in public spaces. One might have briefly locked eyes with a man on the street and found the glance reciprocated, but mostly, one had to know where to go in order to find what he was looking for.

In a city like London, sprawling and ever-transmuting, these spaces of potential have changed over time. Undercover policing in public toilets used for cottaging might have forced regulars elsewhere, while the opening of a new bathhouse could draw men to fresh locations. A new exhibition at The Photographers’ Gallery offers a generous index of these changes and the subcultures they engendered. A Hard Man is Good to Find! maps gay male physique photography and nudes onto the city, creating a visual topography of gay London from the 1930s to the 1990s.

The earliest works in the exhibition depict Highgate Men’s Pond, the communal swimming lake within the larger cruising ground of Hampstead Heath. Twenty-one-year-old artist Keith Vaughan wandered down to the ponds in 1933 with his Leica and photographed swimmers and sunbathers in various states of undress – reclined or tanning in jockstraps. Processing the images in a makeshift darkroom at his mother’s house nearby, Vaughan then assembled the photographs into an album, collaged in the contemporary modernist style and shown in A Hard Man for the first time. “These works were intensely private,” explains curator Alistair O’Neill, a fashion professor at London’s Central Saint Martins. “After Vaughan died [these photographs] were passed onto his closest friends and kept at the back of wardrobes. They’ve only recently come to light.”

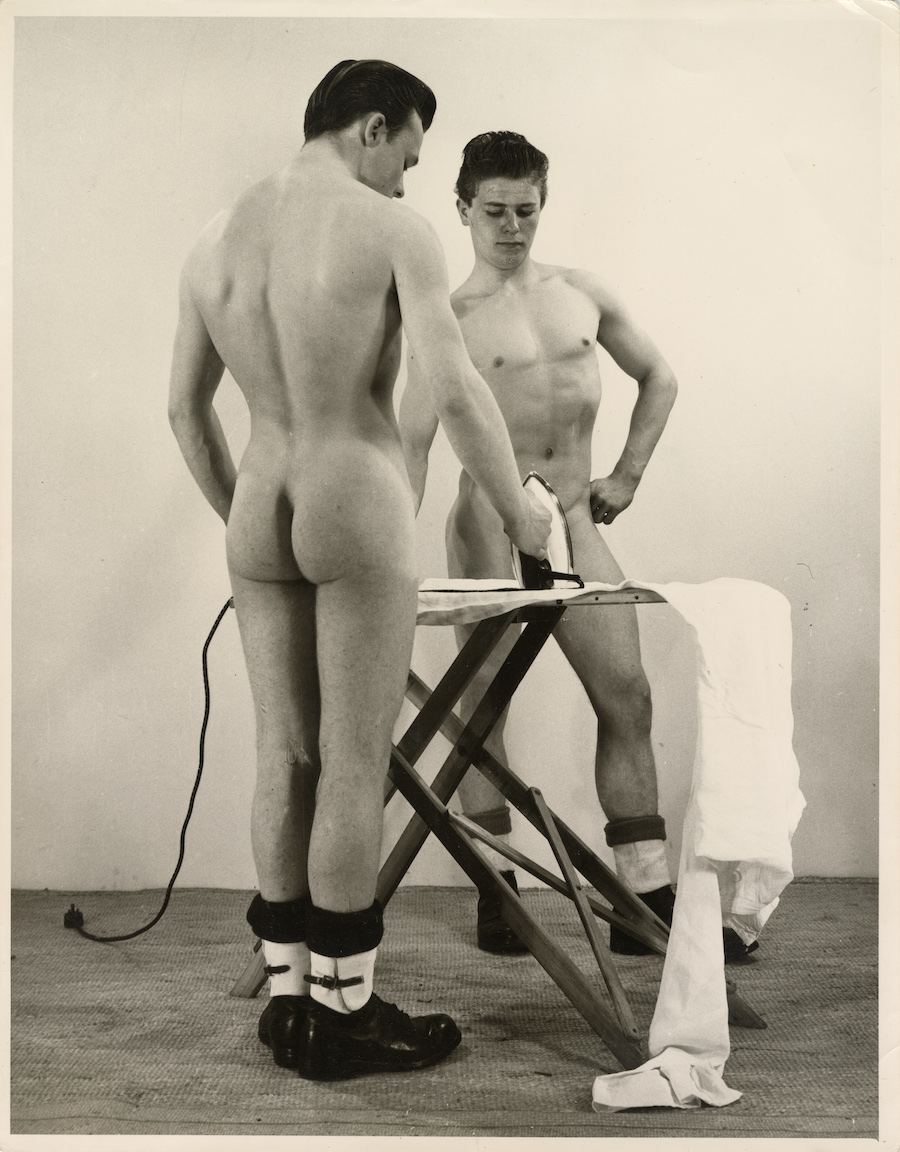

Alongside Vaughan’s shots from Highgate is Between the Barracks, a section of the exhibition focusing on images taken in and around the area between the Wellington and Chelsea Barracks, featuring Montague Glover’s photos of young horse guards in Pimlico. The guards often moonlighted as rent boys who would accompany Glover back to his flat to be photographed – half-nude, half in uniform.

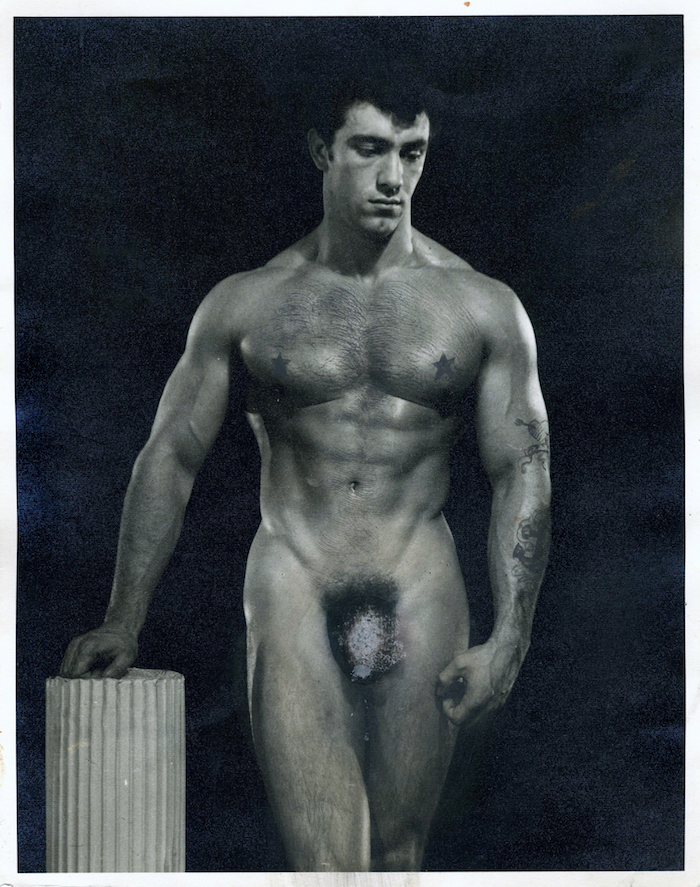

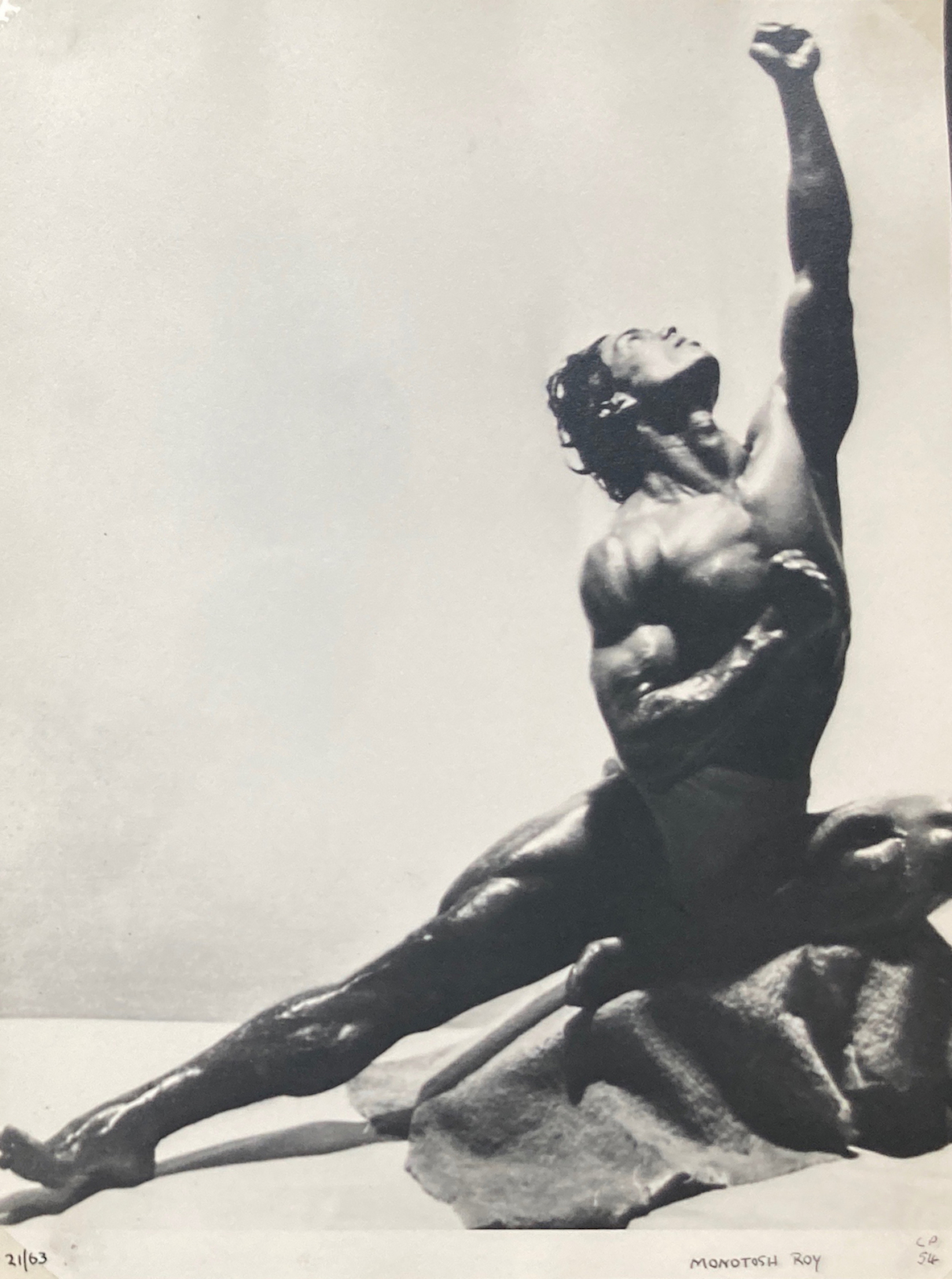

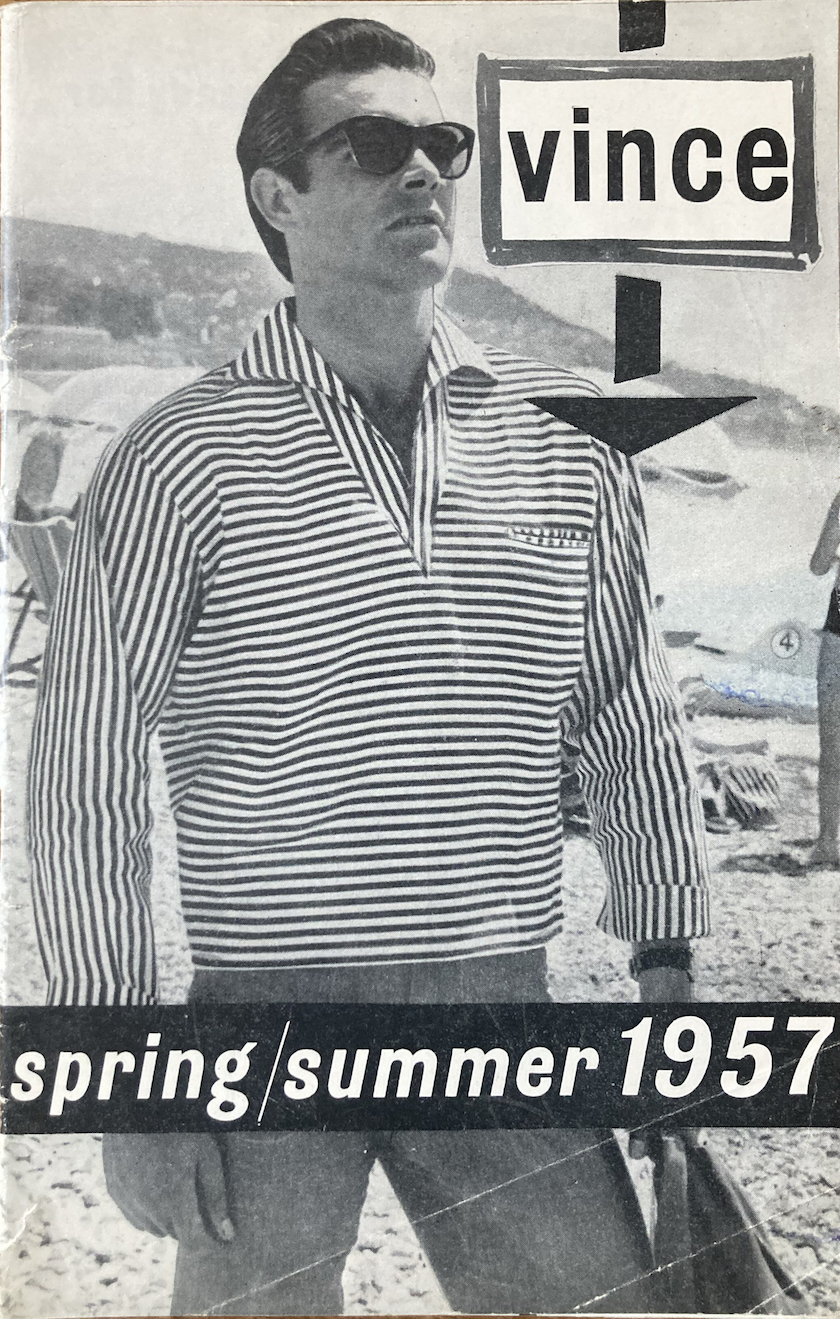

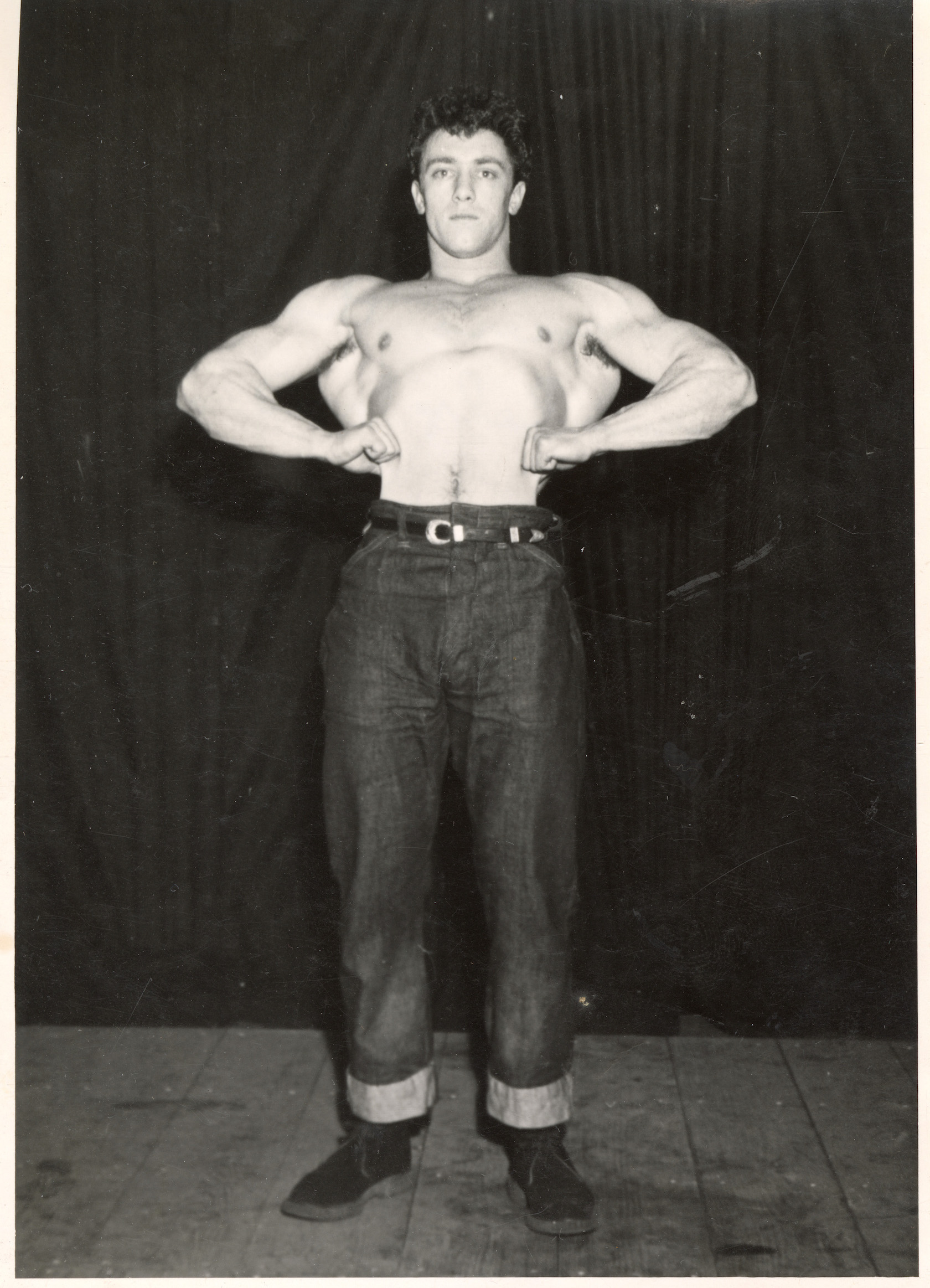

Also included in A Hard Man are photographs shot in Marylebone a decade later, specifically Manchester Street, where Bill Green aka “Vince” set up Vince Studio for physique photography. Here in private, sculpted (and usually young and white) men were photographed in tight underwear that Vince would later sell at his Soho boutique, Vince Man’s Shop. “A little oil on the skin helps by giving a slight sparkle and increases the contrast between the shadows and the highlights of the muscles,” Vince wrote in an article for amateur photographers. Elsewhere on Manchester Street was photographer Patrick Procktor’s studio. In a portrait by Cecil Beaton, Procktor admires two nude life models in 1967.

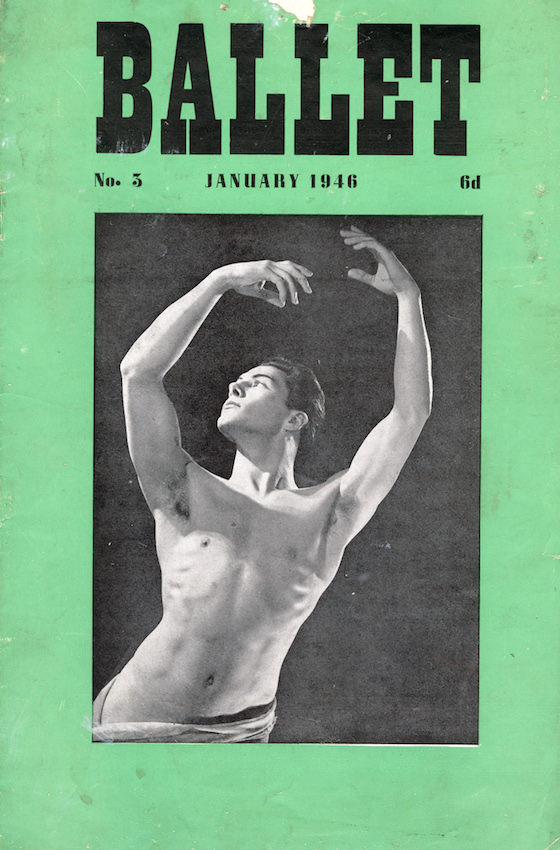

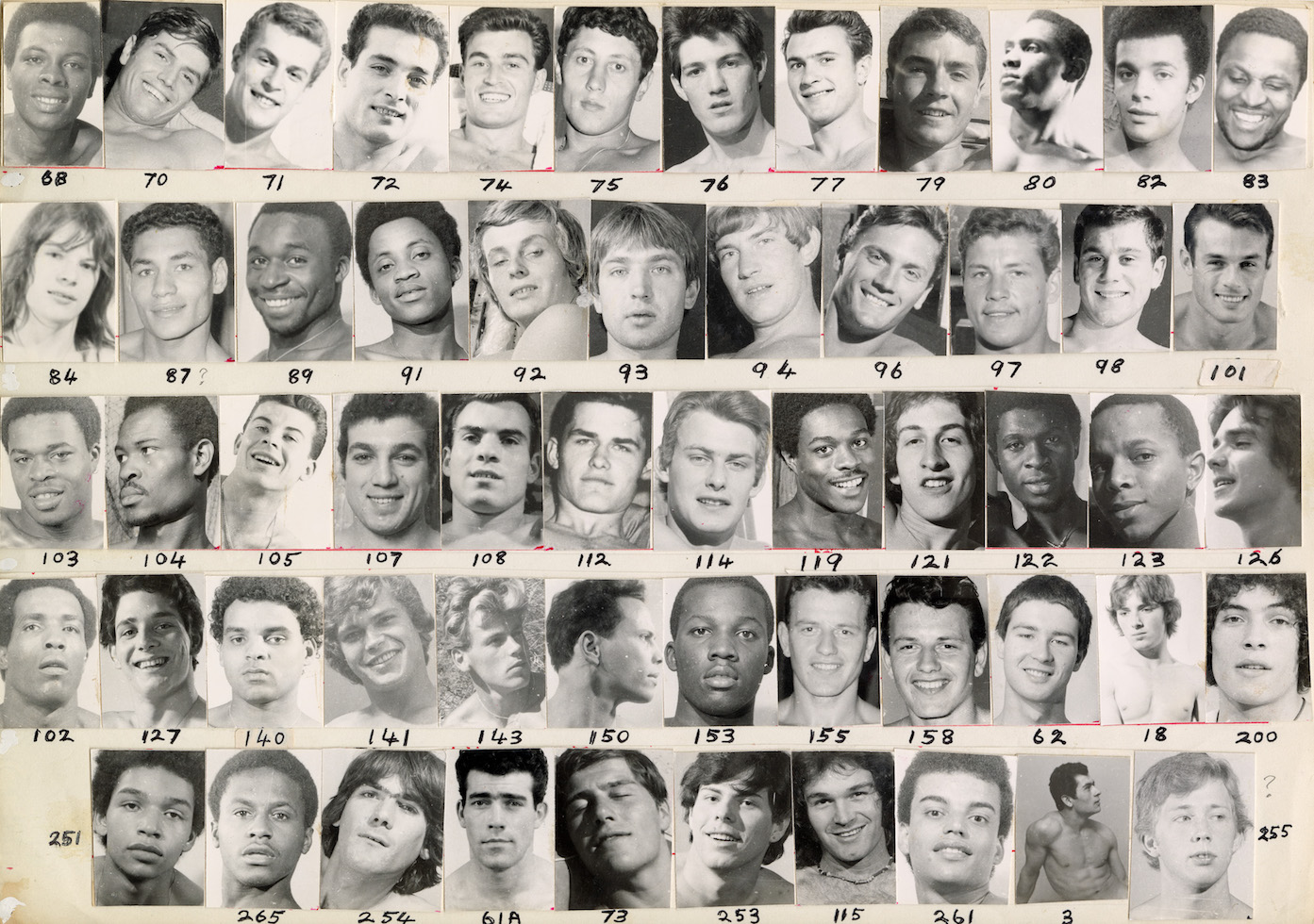

A Hard Man explores the slippery space between ‘official’ physique photography and more amateur or pornographic nudes. The former present men as both glamourised and objectified, almost as we expect to see women’s bodies photographed, and would sometimes segue into the latter. For example, in physique magazines like Man’s World (sold in newsagents), readers could find an advertisement with a catalogue sheet and an address to send off for larger prints. When these would arrive, the model pictured would have a posing patch inked on that could be scratched away to reveal the anatomy beneath.

While the tradition of physique photography – shooting nude or nearly nude men, usually bodybuilders – is not necessarily queer (although, that’s probably up for debate) O’Neill points out how the genre allowed gay and bisexual men to circumvent laws in the first half of the 20th-century, a time when homosexuality was outlawed and possessing homosexual imagery was a criminal offence under the Obscene Publications Act of 1959. “Representations of the male nude came under incredible scrutiny,” he explains. “Ways for men to look at other males in states of undress were limited, partly to sites of physical exercise and sports.”

“Most people were unaware that an unassuming door led to The Backstreet, a dark, leather and rubber fetish space. You entered another world to the hostility in the daily press”

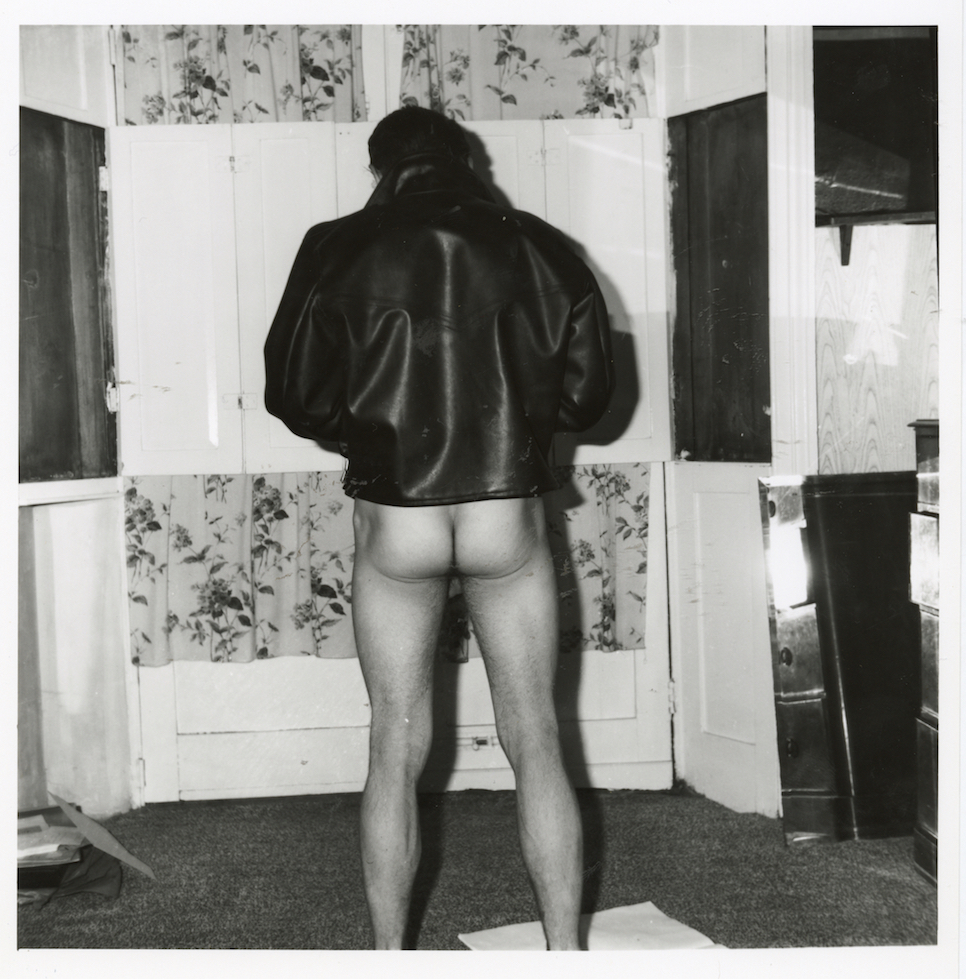

Compared with the show’s photographs from later decades – specifically, images created after the UK’s Partial Decriminalisation of Homosexuality in 1967 – the physique photographs can appear almost modest. An unearthed series of intimate pictures presumed to be taken around Notting Hill in the late-1950s to early-1960s represents a shift from more covert to overt photography practices, showing two men nude, lying intertwined. The negatives were bought on Portobello Road market by British ceramicist and writer Emmanual Cooper and later developed for his collection. They serve as a visual representation of an uninhibited decade of liberation, between Britain’s first Pride in 1972, and the onset of the AIDS crisis in Britain in 1981.

Moving into the 1980s, images taken of young men around Brixton include the fetishistic collages of former co-director of Brixton Art Gallery, Guy Burch, as well as the erotic studio photography created by Ajamu X, mostly of other Black British men. This era represents O’Neill’s departure from traditional physique photography to look at its legacy on gay British fine art photography, right up until the transition from analogue to digital.

A Hard Man demonstrates how the formal aspects of photography can be harnessed to heighten the eroticism of an image. Burch’s collages draw attention to the face, then the crotch, he says, to conjure the cruising look: eye contact held a moment too long, then a glance downwards. Others use light and dark to fragment the male body, isolating certain parts of it. When the men are wearing clothing, the camera hones in on gay male signifiers like key chains, hankies, stonewashed tight jeans, check shirts and tan boots. “That look was one the physiques photographers moulded,” Burch says. “Clothing as a secret language of availability and provocation.”

Burch, who has lent works to the show, is prompted by its trajectory to reflect on his own experiences in 1980s and 90s London, a time when the city’s sexual loci were more concealed. Back then, “it very much felt that our lives and spaces were under attack,” he says. “Most people were unaware that an unassuming door [by Mile End station] led to The Backstreet, a dark, leather and rubber fetish space. You entered another world to the hostility in the daily press.” In this context, the purpose of A Hard Man is to open up “the hidden map of London, the one others don’t notice,” Burch explains.

“The exhibition celebrates men for continuing to make this imagery for themselves and the community,” O’Neill reflects. Cruising, as well as photography, “was not without risks,” Burch adds. “There is a challenge or dare aspect of it… that is why I’m drawn to gay physique images in general. We know the photographer fancied the model; some respond [to that feeling], others do not. This odd amalgam of the directness of porn with the demands of censorship has an edginess – is he or isn’t he… will he, won’t he?” Burch hopes that by visiting A Hard Man, visitors can experience that unique thrill themselves.

A Hard Man is Good to Find! is at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, until 11 June