All images © Kalpesh Lathigra.

Turning his polaroid studio express camera on a wide range of subjects, Lathigra interrogates universal themes that underpin photography and society

Stashed in a drawer or tucked into the back of one’s wallet is the most ubiquitous portrait of all – the passport photograph. In the UK, a small-sized photo is required for a driving licence, a passport, age identification to buy alcohol, to open a bank account or to go to school. While its primary function is to confirm one’s identity according to a tight set of binary categories, the most pertinent questions surrounding the image are not about the individual in the photograph but the very portrait itself. What is the relationship between identification photography and the right to freedom? How do these portraits cultivate concepts of nation, belonging and access? How do they define who we are and how we live?

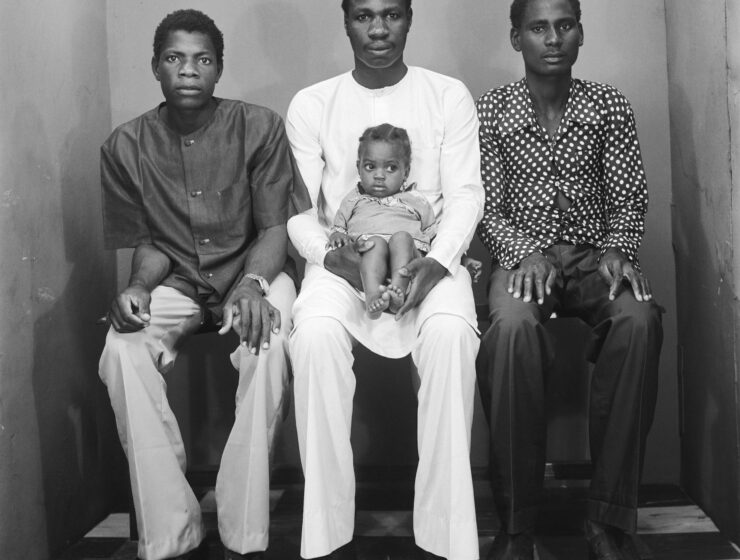

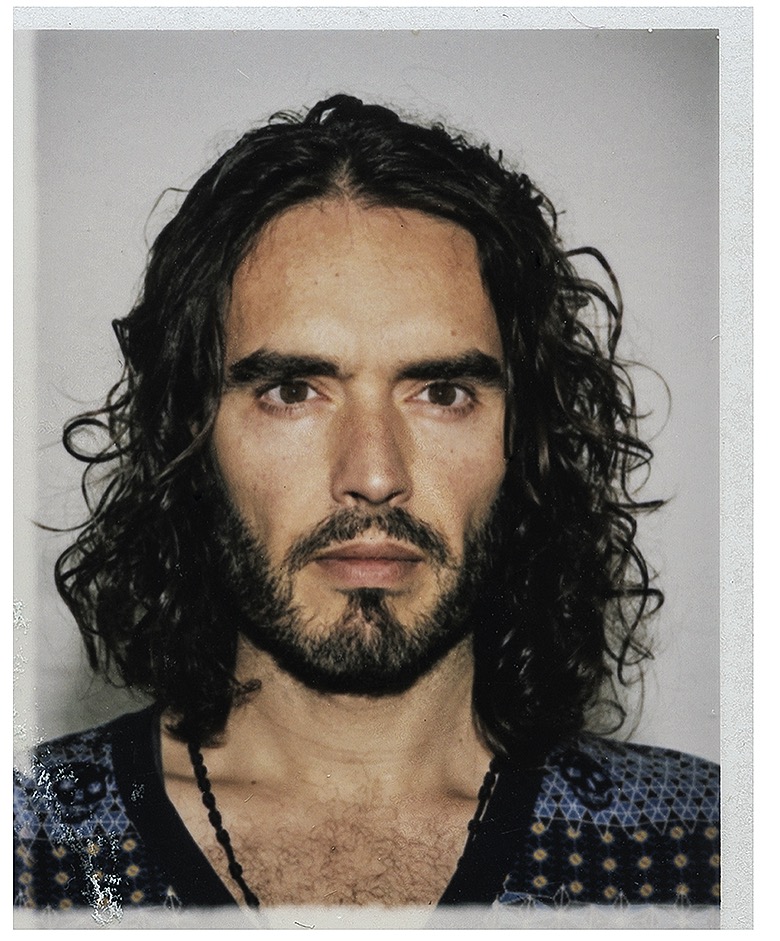

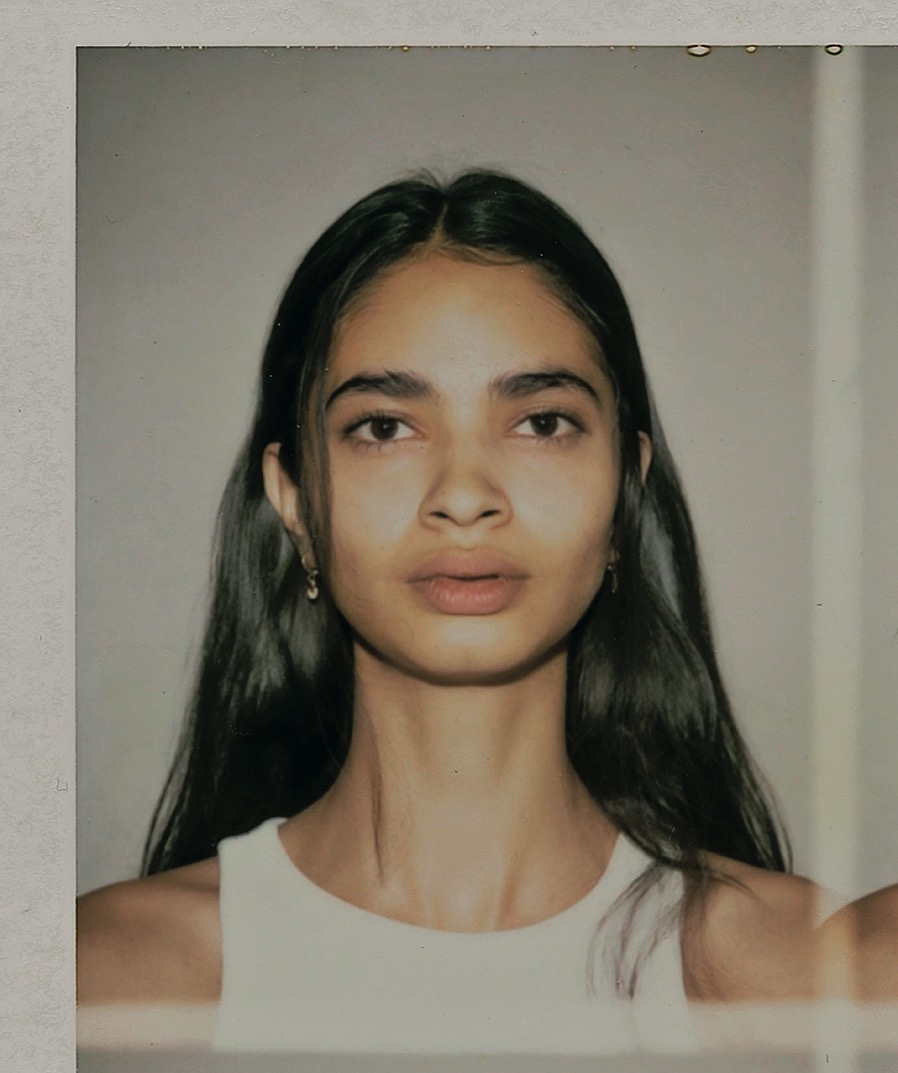

Kalpesh Lathigra has been meditating on these questions for the last decade in a body of work called A Democratic Portrait – an interrogation of ”the one photograph that we all have“. The series contains over 50 passport photographs of cultural figures, politicians, refugees and individuals from marginalised communities, as well as the London-based artist’s friends, family and peers. For Lathigra, the project is about presenting an egalitarian vision of humanity, while confronting ideas around visual literacy and how images are used to assert value and hierarchy. And yet, the project continues to unravel into a broader study of portraiture, power and the changing dynamics of photography itself.

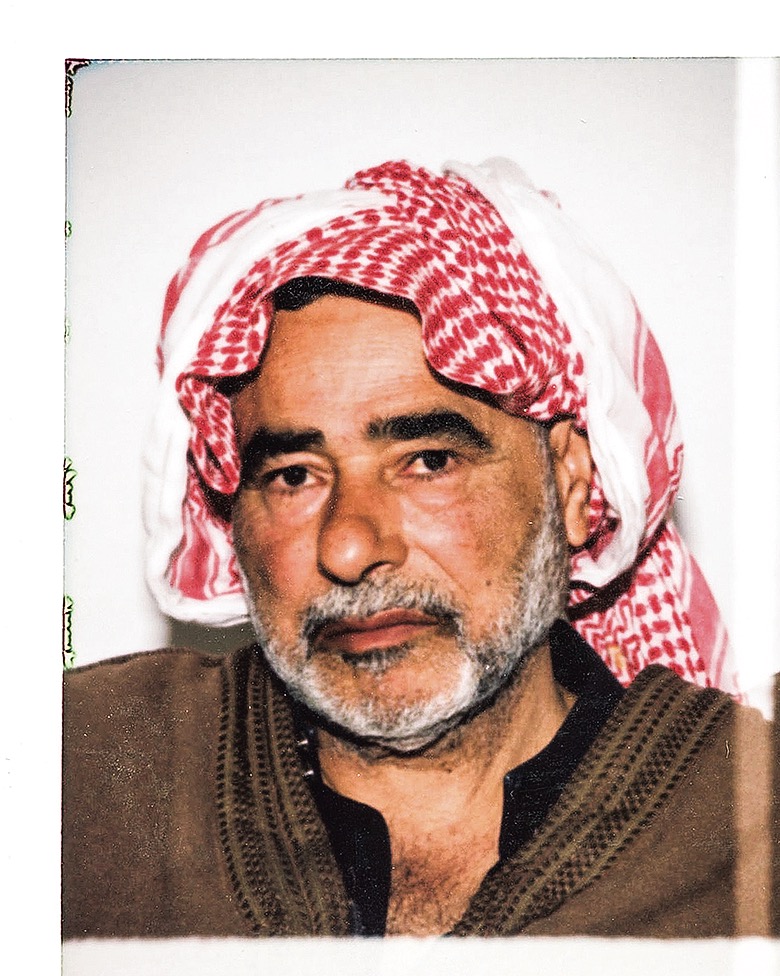

An assignment in 2013 from the United Nations to document the Za’atari, a refugee camp in Jordan taking care of Syrians, was the experience that sparked the beginning of A Democratic Portrait. “I’d always been working with NGOs,” says Lathigra, who was a photojournalist at the time. ”Back then, I was beginning to question how I take pictures, what images of refugees mean, and how they are used and read. Documenting hard news was my job, but I had no control over the usage, and it was an issue for me that images could be used as propaganda. As photographers, our subjectivity is critical and realising this eventually pulled me away from photojournalism.“

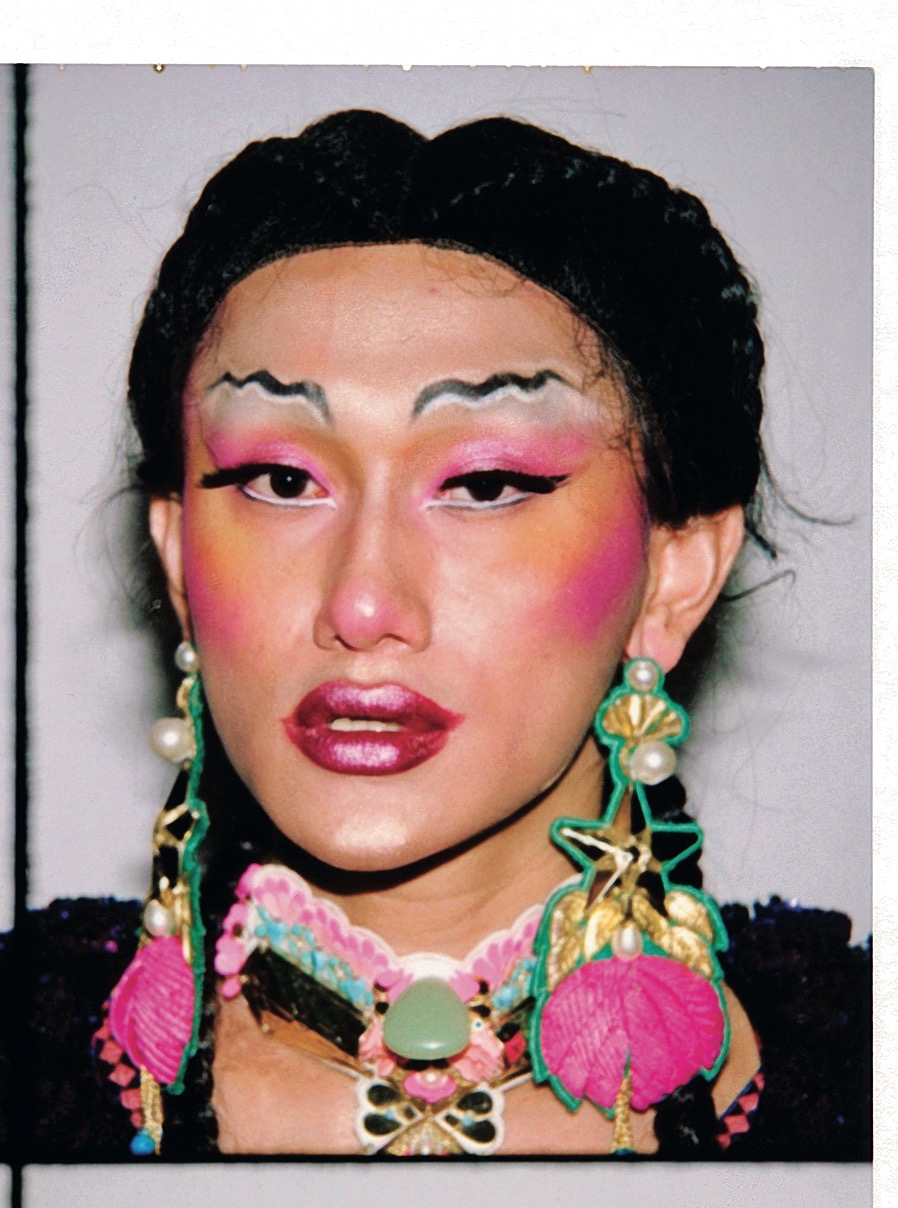

“In a typical portrait set-up, it’s a theatrical moment of being photographed. When you pull out this weird contraption [Polaroid Studio Express] they understand it’s a passport camera. They know to stay still and look directly into the lens. Most people don’t smile. They take on a very different visual nuance in the way they perform.”

Lathigra returned to Za’atari multiple times taking a Polaroid Studio Express – a simple four-lens camera used to take UK passport photos. He began making portraits of refugees in an attempt to expose the privilege and inequalities deeply ingrained in photo IDs – highlighting how human rights and freedom of movement are intrinsically tied to race and country of origin. While Lathigra’s primary line of inquiry was rooted in the politics of the state, the project marked the beginning of a transition in his practice from classic photojournalism to contemporary documentary. As his intentions shifted, new approaches emerged. In A Democratic Portrait, the camera becomes an access point, while the photograph unlocks the sociopolitical implications of our relationship to the medium as individuals and society.

Around this time, Lathigra pivoted into portraiture. When he worked on editorial assignments, he was intent on making more of the commissions and began taking the passport camera with him. At the end of every shoot, he reserved a little time to make a photo of willing sitters. ”Photojournalism was changing,” he says. “Magazines no longer had the budget to send photographers away for months at a time to make an in-depth photo essay. Pivoting to portraiture was about survival.” He adds: “I wanted to offer my clients something different, but I also realised taking a great portrait of someone was not enough for me. I became an artist because I wanted to impact [social] change in one way or another. As a photojournalist, I had this rose-tinted view of changing the world – but it didn’t happen like that. These ideas about the portrait and its role in society matter. For me, if the audience is asking questions, then I’m doing my job.“

The first celebrity Lathigra made a passport photo of was Joan Collins [top]. She agreed as long as she could have time to prepare. With her smoky eyes, red lips, bare décolletage and soft black curls falling around her face, the image bears an uncanny resemblance to Andy Warhol’s 1985 Polaroid portrait of Collins. “She took control,” says Lathigra about the picture. “She knew exactly what she was doing.” Sittings with former PM Tony Blair, and music stars Mark Ronson and Lykke Li quickly followed, and soon magazines began requesting a passport photo as part of their commissions.

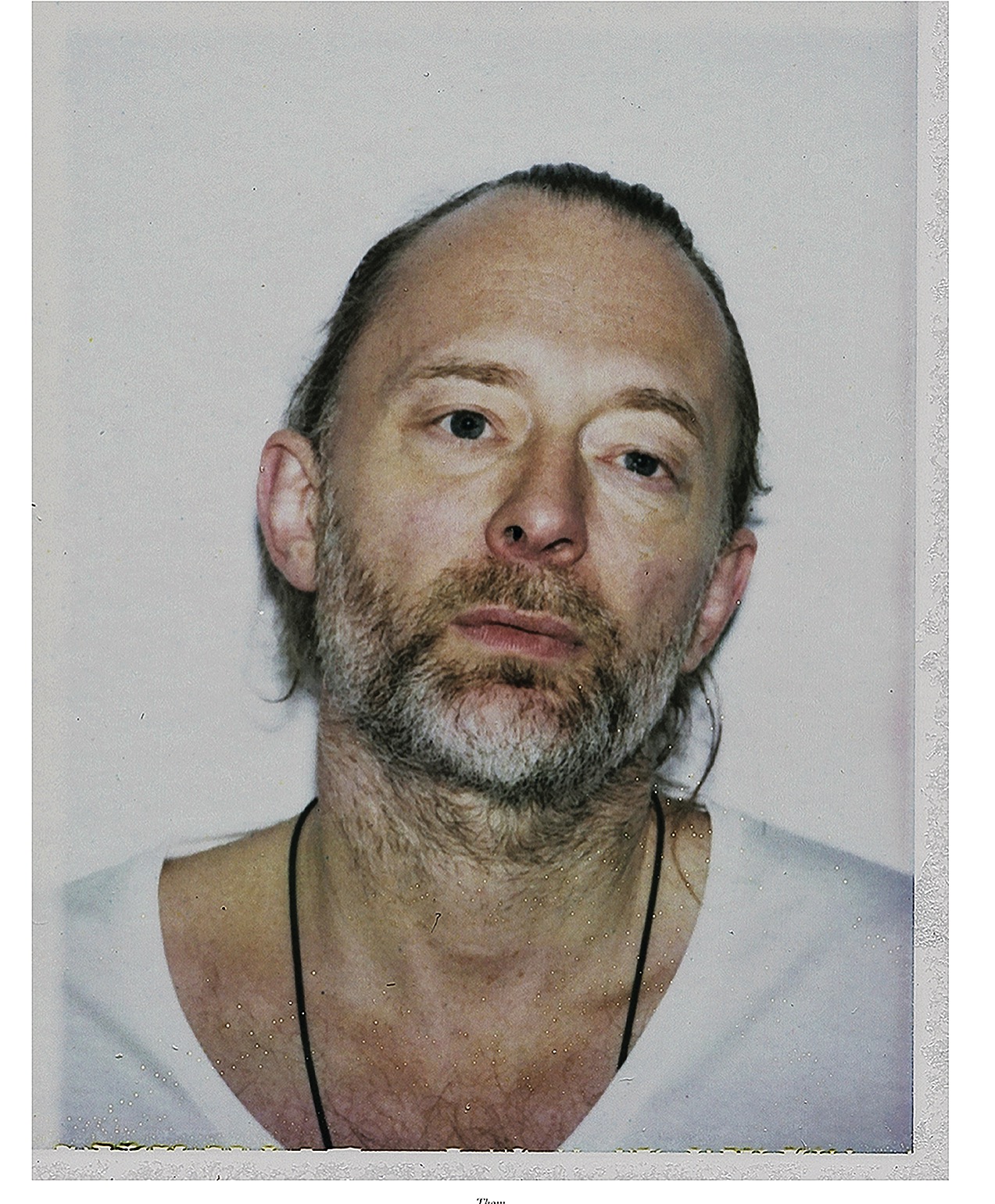

After the experience with Collins, Lathigra paid close attention to how individuals would code-switch depending on which type of image he was making. “In a typical portrait set-up, it’s a theatrical moment of being photographed,” he explains. “Even if I try to break that down with rapport, it’s very difficult. If you’re a person of prominence, you’re trained to act a certain way in front of the camera. When you pull out this weird contraption [Polaroid Studio Express] they understand it’s a passport camera. They know to stay still and look directly into the lens. Most people don’t smile. They take on a very different visual nuance in the way they perform. [Radiohead’s] Thom Yorke was the only person beyond Collins who challenged this dynamic – [in one pose] his hand came up, covered his eye, and created an entirely different image.”

“When I brought the passport camera into the editorial context, I was questioning social media, how the audience reads celebrity photographs and the democracy of picturemaking in an era where everyone can take a good one. The power balance had shifted, and I wanted to talk about that. It was no longer just about how we control our image – in terms of how we look and want to be seen in the world – it was also about how these images of celebrities and influencers had become financial assets.”

In Listening to Images, the scholar Tina Campt writes, “Even in the most constrained formats of photography – like the mugshot, the ethnographic image, the passport photograph – there is some enactment of a persona”. The sentiment is alive in Lathigra’s images, from the tilt of the head and a sly smirk to a held jaw and piercing eye contact – these subtle gestures of world-renowned faces make these images captivating and relatable.

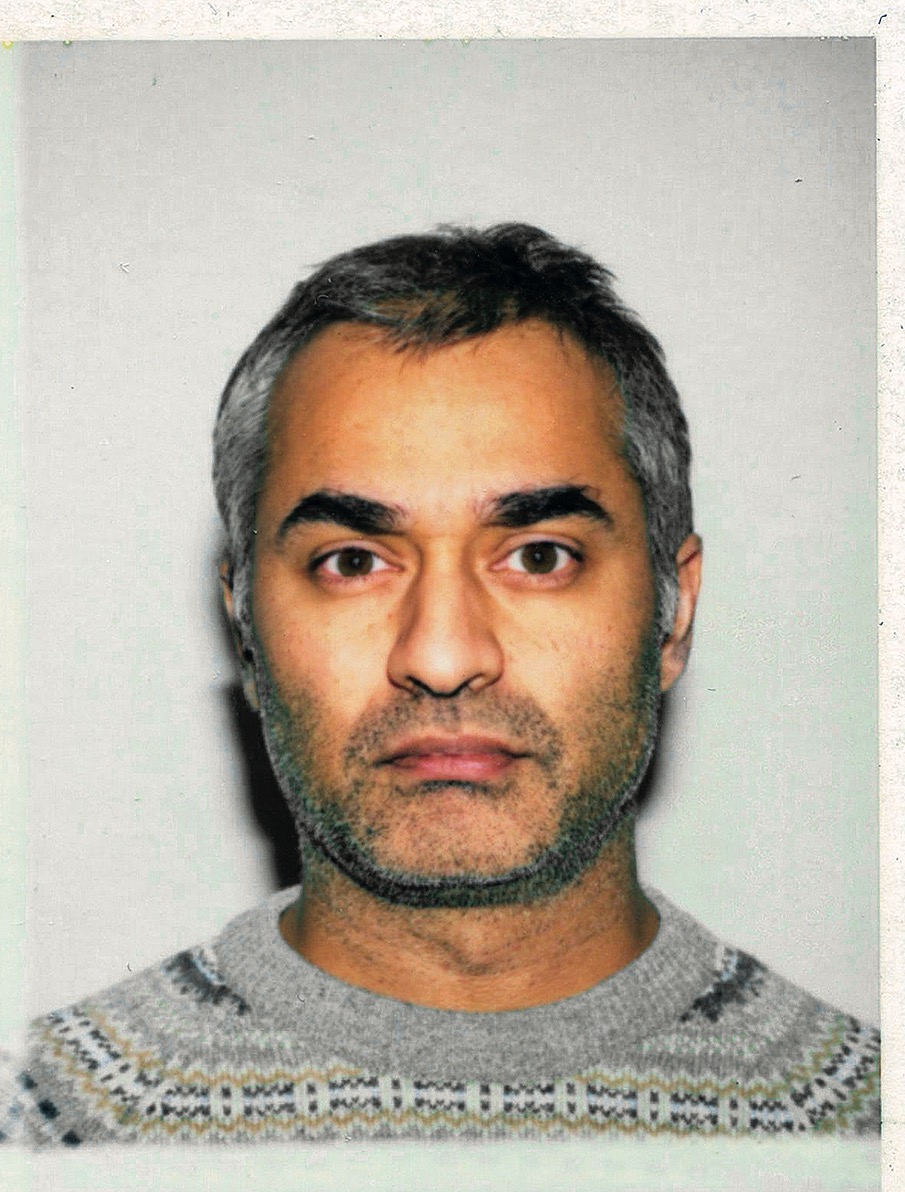

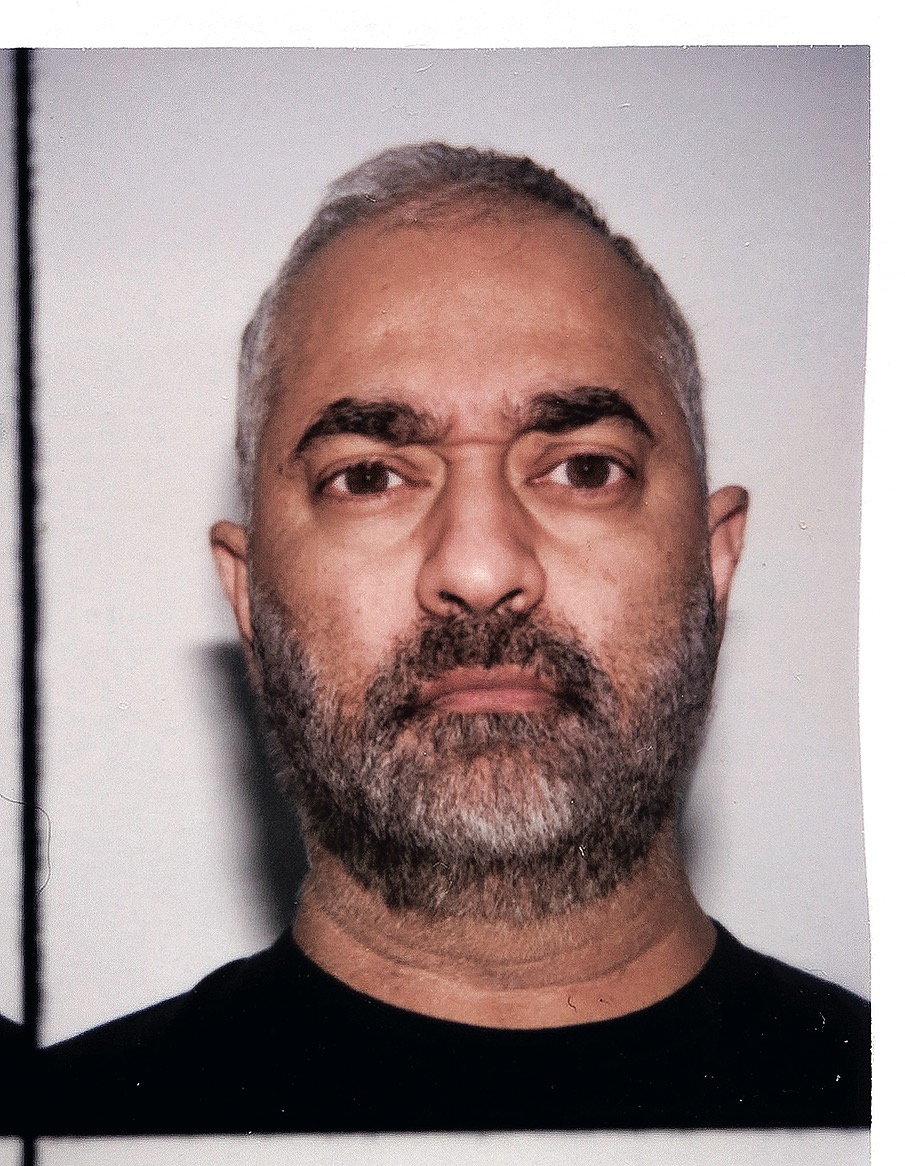

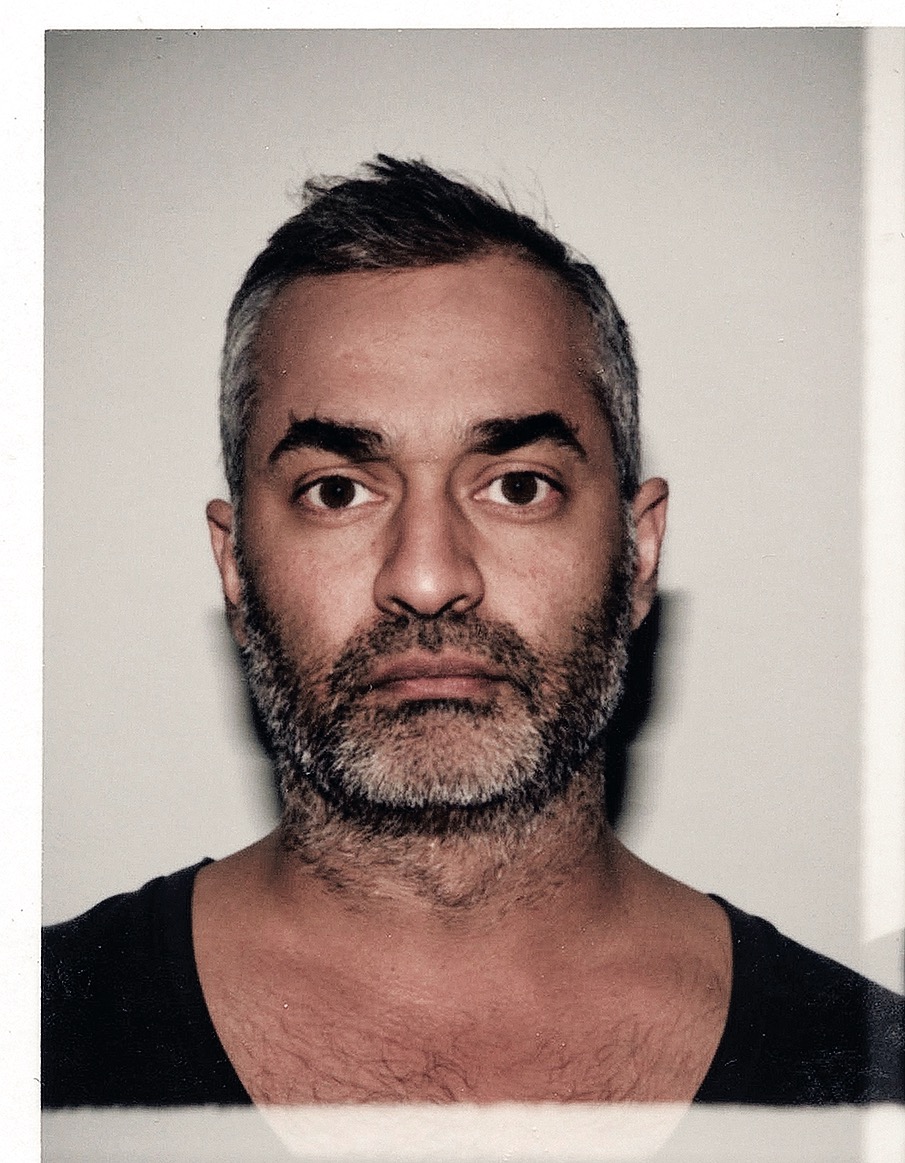

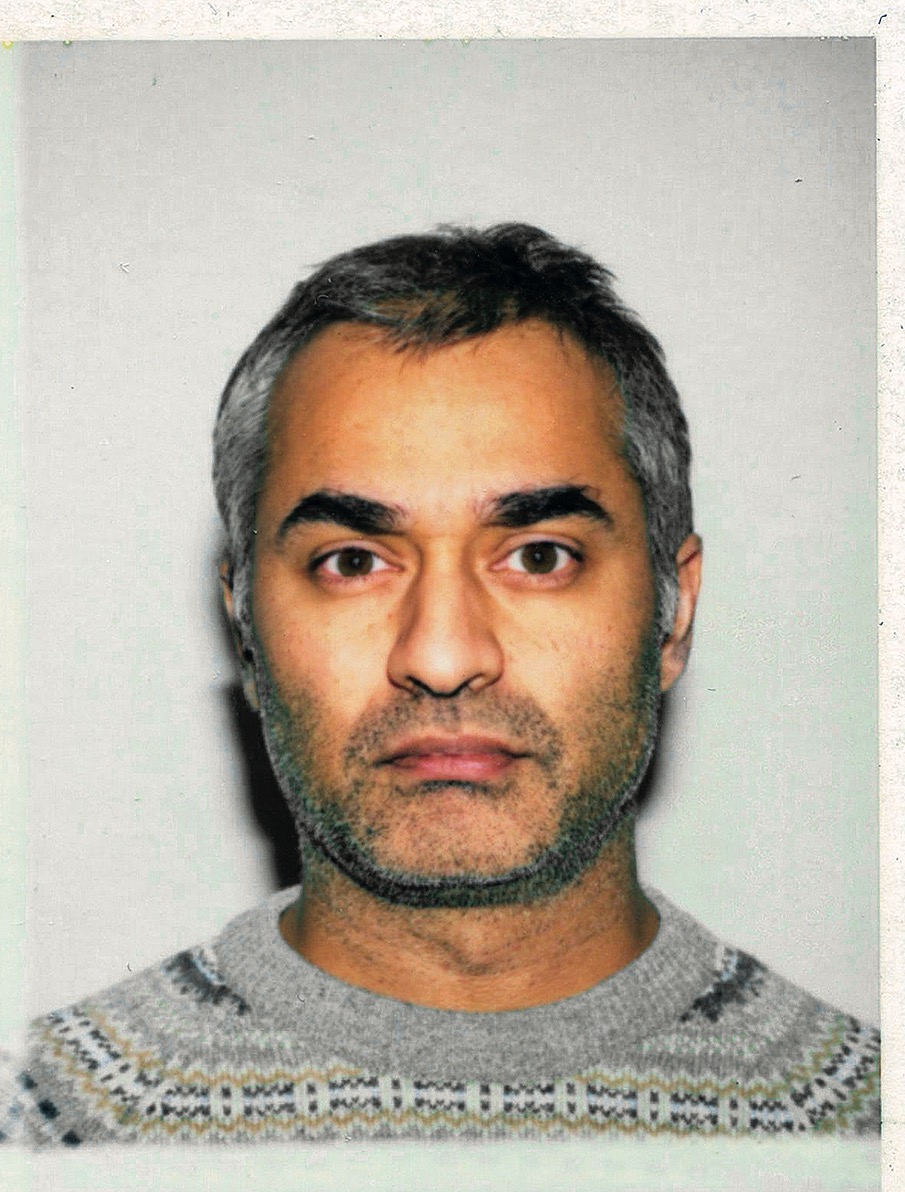

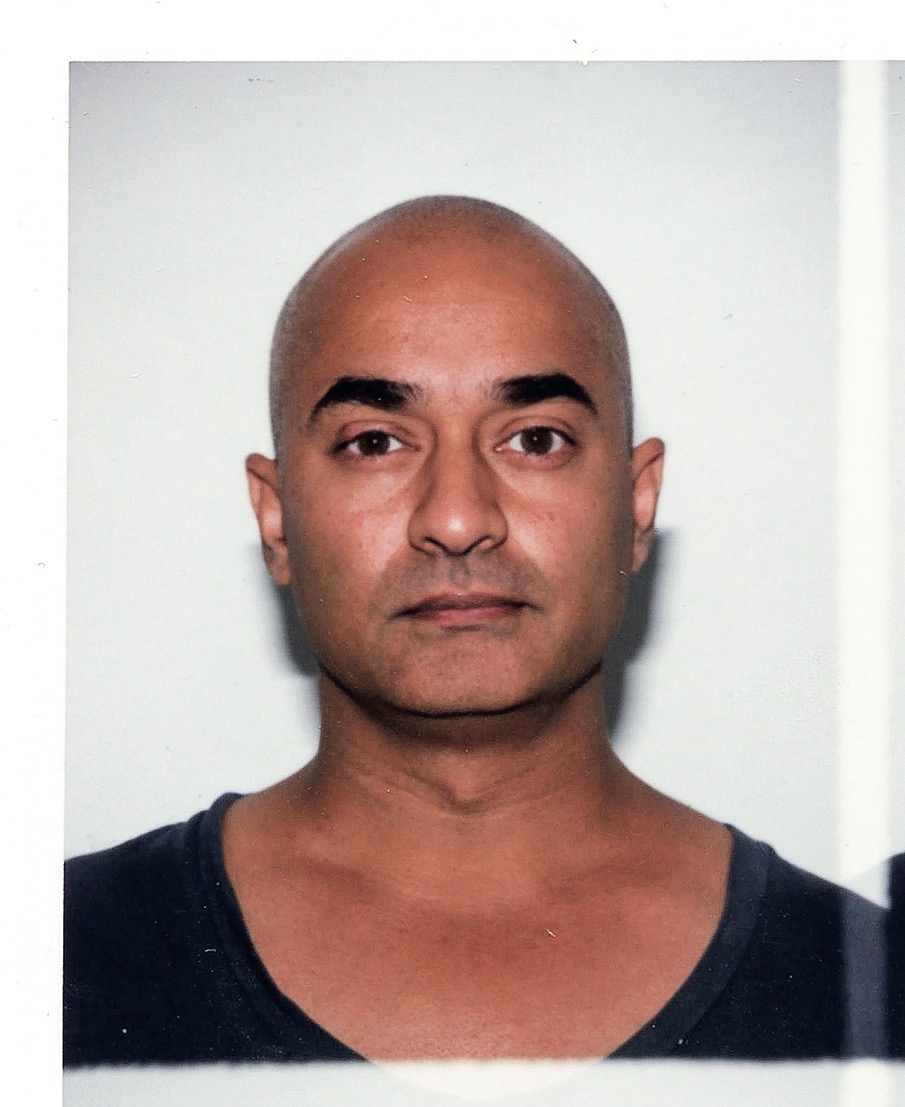

Lathigra felt it was important to include himself in the series too. His self-portraits [below] are a poignant rumination on the intersection of masculinity and ageing that often remains hidden in contemporary culture. A direct investigation of how we hold space, what we reveal and what we hold back. “It’s important for me to be in the project if I’m asking all these different people to be open to the process,” he says. “But the self-portraits are difficult [to make] and hard to look at sometimes. It’s a boundary I didn’t think I would cross because of my vanity and ego. I have real difficulty accepting that I’m getting older, and it’s something I don’t think men talk about. Making these images has been about confronting myself.”

Intentional nuance, multiplicity and contradiction make up the conceptual force of A Democratic Portrait. Lathigra allows ideas to overlap and entangle, building narrative threads that speak to the lineage of portraiture and its contemporary evolution. The project occupies space between Warhol’s Polaroids and Luc Delahaye’s Portraits/1 while also being in dialogue with work such as Taryn Simon’s A Living Man Declared Dead and Steve McQueen’s Year 3, which centre on ideas of civic and national identity while interrogating notions of the individual and the collective, status and value.

For Lathigra, it was also vital to address how the rise of social media and the creator economy is reconfiguring portraiture in unexpected ways. “When I brought the passport camera into the editorial context, I was questioning social media, how the audience reads celebrity photographs and the democracy of picturemaking in an era where everyone can take a good one,” says Lathigra. “The power balance had shifted, and I wanted to talk about that. It was no longer just about how we control our image – in terms of how we look and want to be seen in the world – it was also about how these images of celebrities and influencers had become financial assets. What does this mean for the medium in five or 10 years?”

He continues: “If you think about the history of portraiture – the pictures of celebrities from the past, whether it’s Eve Arnold’s photos of Marilyn Monroe or Dennis Stock’s of James Dean – there is authorship in their work. Instagram has changed that, and now celebrities have provenance.” Today, it is more likely that the agent selects the photographer for a shoot, taking the decision away from the photo director on set. Often the photographer is also asked to release the image’s copyright. “This is uncomfortable for me,” says Lathigra. “I wanted to challenge this new realm of control by taking it away. In making this very direct, uniform image, the promise of the project was about equality – everyone being photographed the same way.”

A Democratic Portrait is an assemblage of faces that unravels various ideas from identity, celebrity culture, and influence to freedom of movement, access, race and refuge. As a series, the project goes full circle. It subverts the terms of ID photography – to control, track and categorise people – and instead uses it to present a collective picture of humanity.

“On some level, who we are as human beings, and as a society, give prevalence or ascribe value – therein lies the democracy of passport photography,” says Lathigra. “This project stems from my romantic notion that we are all a society. I’m still interested in the same ideas and stories [10 years later] because they matter. The threads that bind my work have always been to provoke the viewer to think about where they stand. It’s a different world from when I started, and I think the full evolution is yet to come.”