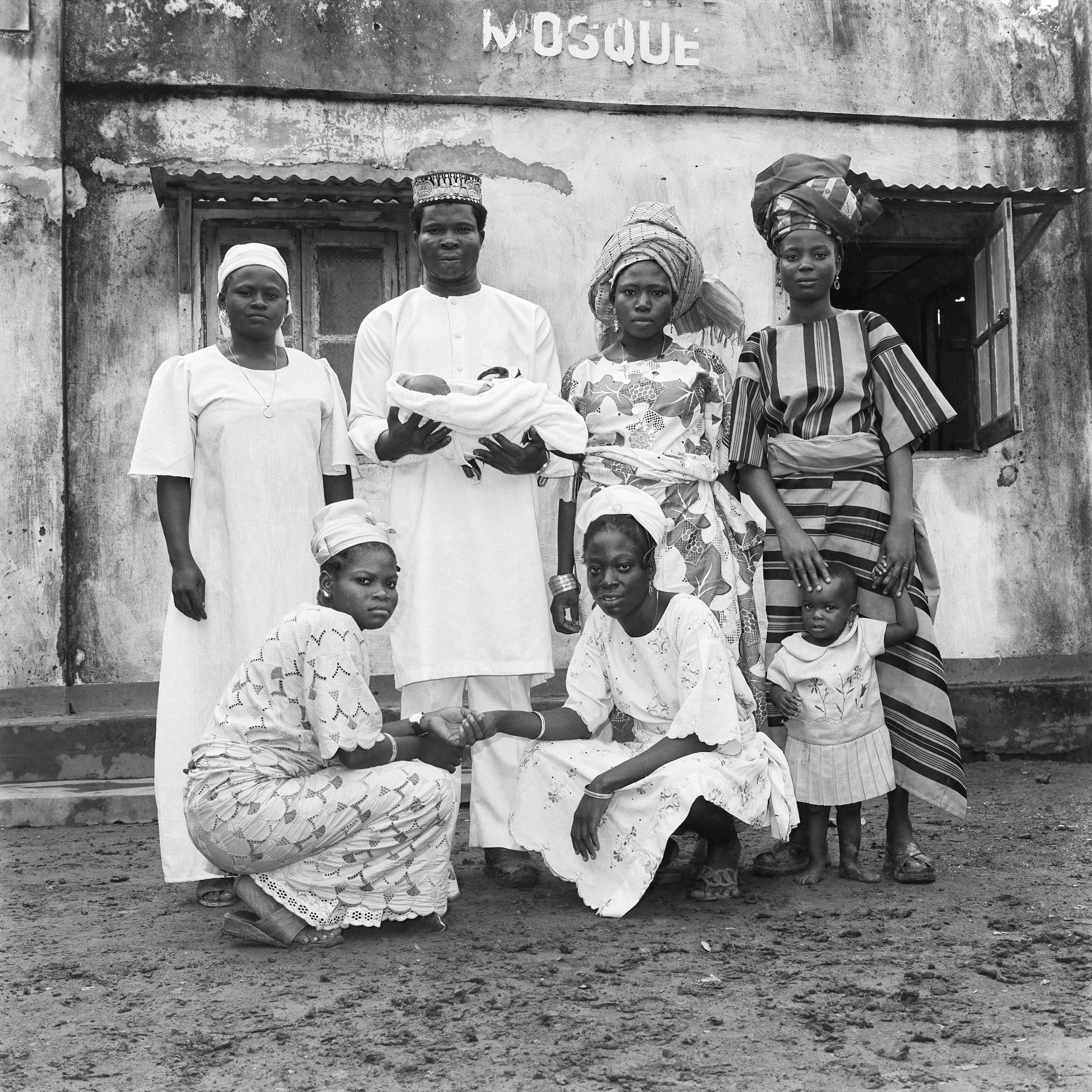

© Abi Morocco Studios, courtesy of Autograph Gallery

The Spirit of Lagos showcases the vibrant portraits captured by Abi Morocco Photos, highlighting a cultural transformation during Nigeria’s post-oil boom era, Emma Russell finds

There’s a portrait of husband-and-wife duo, John and Funmilayo Abe, taken at Abi Morocco Photos — the studio they owned on Aina Street in Lagos — that captures the energy of the city in the 1970s. They’re stylishly dressed: John in a collared shirt tucked into his chequered trousers; Funmilayo wearing a pretty white polka dot mini dress, holding their medium format camera. The patterned curtains frame an otherwise spontaneous image in a style of portraiture popularised throughout West Africa. “[The studio] was a space for performing and dreaming,” says Karl Ohiri, who founded the Lagos Studio Archive to preserve images like this, with his partner Riikka Kassinen.

It’s one of the many photographs from Abi Morocco’s expansive archive, spanning from the 1970s to 2006, that chronicled the street-style capital in staged solo shots, family portraits, and images from traditional events. In the ‘70s, Lagos was thriving — Nigeria was celebrating a decade of independence from British colonialism, the end of the war, and an oil boom that had triggered its soaring population. “There was just a general optimism in the country,” says Ohiri. “John and Funmilayo really loved that time because things were cheap and fresh. Buildings were coming up, the roads were clear, it was the beginning of this city, this cosmopolitan city coming into being.” Works from their first year in operation are now on show in a new exhibition at Autograph gallery, Spirit of Lagos.

“I was interested in how John and Funmilayo were going into these domestic houses and crazy interior designs and crashing patterns and how they took that same formula onto the street”

Studio portraits offered a way for city-dwellers to show their newfound wealth and aspirations to family and friends. In one portrait, a woman wears a new outfit that’s clearly been newly unboxed with creases down the front where it’s been folded. Others read detective books from abroad or look seriously at the camera in their favourite sunglasses. “Everybody would receive these images almost like postcards,” says Ohiri, whose mother had her own portrait taken at Lucky Star Studio in Lagos before she emigrated to the UK. Across West Africa, the portraits took on a distinct quality: the black and white portraits of clients dressed in their finest were taken against chequerboard floors and floral patterned curtains. “They look the same but that’s really nice to see because it’s a constant reminder that it’s all part of the human condition,” says Ohiri, “they’re all chasing the same dreams and aspirations and same things.”

Young people would pose with their new phones and radios or their scooters and guitars — adopting the trends of an era. It was a time of music and creativity with British and American rock bands finding popularity in Nigeria, as well as local Afrobeat legend Fela Kuti, King Sunny Adé and Victor Uwaifo. At home, teenage boys were photographed in their bedrooms with images of naked girls cut out of magazines on their walls. “With film there’s this relationship between the photographer and the sitter, which is really about just the moment that we’re having. There’s more styling and there’s more time to compose the shot.”

“You see this idea of kinship and community and how these different people that were there were known to John and Funmilayo, and you see the warmth in the way they capture the essence of who they were,” says senior curator Bindi Vora. “I think there can be some misconceptions about African studio photography being of a very particular volition but what we are seeing here is the fashion, the culture was everywhere: it was at their homes, in the street, in the studio. It was how they were.”

John and Funmilayo Abe were a power house couple, raising their eight children with the help of their many studio assistants. John would go out to funerals, weddings, naming ceremonies, and freedom parties (a right of passage ceremony); while Funmilayo would hold down the fort. She’s one of the few female practitioners to have been credited so prolifically in such a male-dominated field. “We’ve always had this idea about reinserting some of these histories that have been obfuscated or left out of the canon when it’s not about discovering them, it’s about saying they’ve existed and these are the missing chapters,” says Vora.

“I was interested in how John and Funmilayo were going into these domestic houses and crazy interior designs and crashing patterns and how they took that same formula onto the street. It was telling a bigger story about what it was like to run a commercial studio at that time and how you were constantly having to adapt and constantly change,” Vora adds. But the images were never supposed to be seen in the context of a gallery space, so the framing of the photographs reveals more to the viewer than what would have been presented to the customers: the different floor types, props, lamps and backgrounds. “I think that’s one of the interesting things in many ways is how we readdress these images.”

Ohiri and Kassinen are on a mission to preserve as many photography archives, like Abi Morocco’s, before it’s too late. With the heat worsening and the summer’s humidity threatening the negatives; Lagosians getting pushed further from the city’s centre; and studio owners dying (shortly after they finished their project and research, John passed away) — the portraiture that defined an era is at risk of being destroyed. “I didn’t want this cultural heritage to be lost,” says Ohiri. “There were only a handful of photographers that were there.”