All images © Jet Swan

Slowly but surely becoming a star, the photographer took an unusual route into photography and maintains an idiosyncratic approach to commissions

Jet Swan is really Jet Swan’s name, though she did have an extra surname she jettisoned; like her work it suggests how rich and strange life can be, actual life without recourse to fiction, or with only a little editing. Born in 1990 in Yorkshire, Swan published a book, Material, in 2021 with Loose Joints, and has shot several high-profile campaigns; beyond that there is little information about her. Swan is a big watcher, which is perhaps why she has stayed in the background, even when she has gone in front of the camera. In fact she has shot hundreds of self-portraits which are somehow not known as such, and which seem almost eerily detached. Her gaze is intensely personal yet somehow also coolly sociological, suggesting discussions around the ‘female gaze’, voyeurism, and the role of the photographer.

Her vision is so idiosyncratic it is not surprising she has become successful, in fact, though she made her way via an unconventional path. Creative from a young age but not academic, she left school at 16 to study tailoring and pattern cutting, which was “very, very technical”. Aged 18 she moved to London, working in fashion then finding her way back to education and a BA at Central Saint Martins. Swan had been taking photographs since her teens but initially only to document other projects; somewhere along the way she got interested in images as images, and started following impulses still evident in her work. Her final project at Saint Martins was a study of legs on a Saturday night. “I went to West Street, Sheffield, which is a real going-out street, with loads of amazing girls with really short skirts and incredible legs,” she says. “Legs in tights or just shined up, men going after them, really messy, really fantastic.”

“What I prefer is the more human side, the less performative side. I’m rarely influenced by fashion photographers”

She also travelled to Russia around this time, setting up an impromptu studio and shooting only women; on graduating she did not immediately pursue photography though – or at least not as a career. “A lot of my peers started being photographers but I just kind of disappeared,” she says. Actually she was still working, without showing anyone, shooting outside her many freelance jobs. By 2019, she was living in Ramsgate, a coastal town two hours from London, and intensively making images. “My main thinking was, ‘I just need to earn enough money to be able to keep on making this work’,” she says. “I could have done that forever, just kept working quietly – I was just really into the work, and felt like it was feeding me. It was very internal, like a conjuring, which is a strange word to use but I had a real push to have that feeling of satisfaction.”

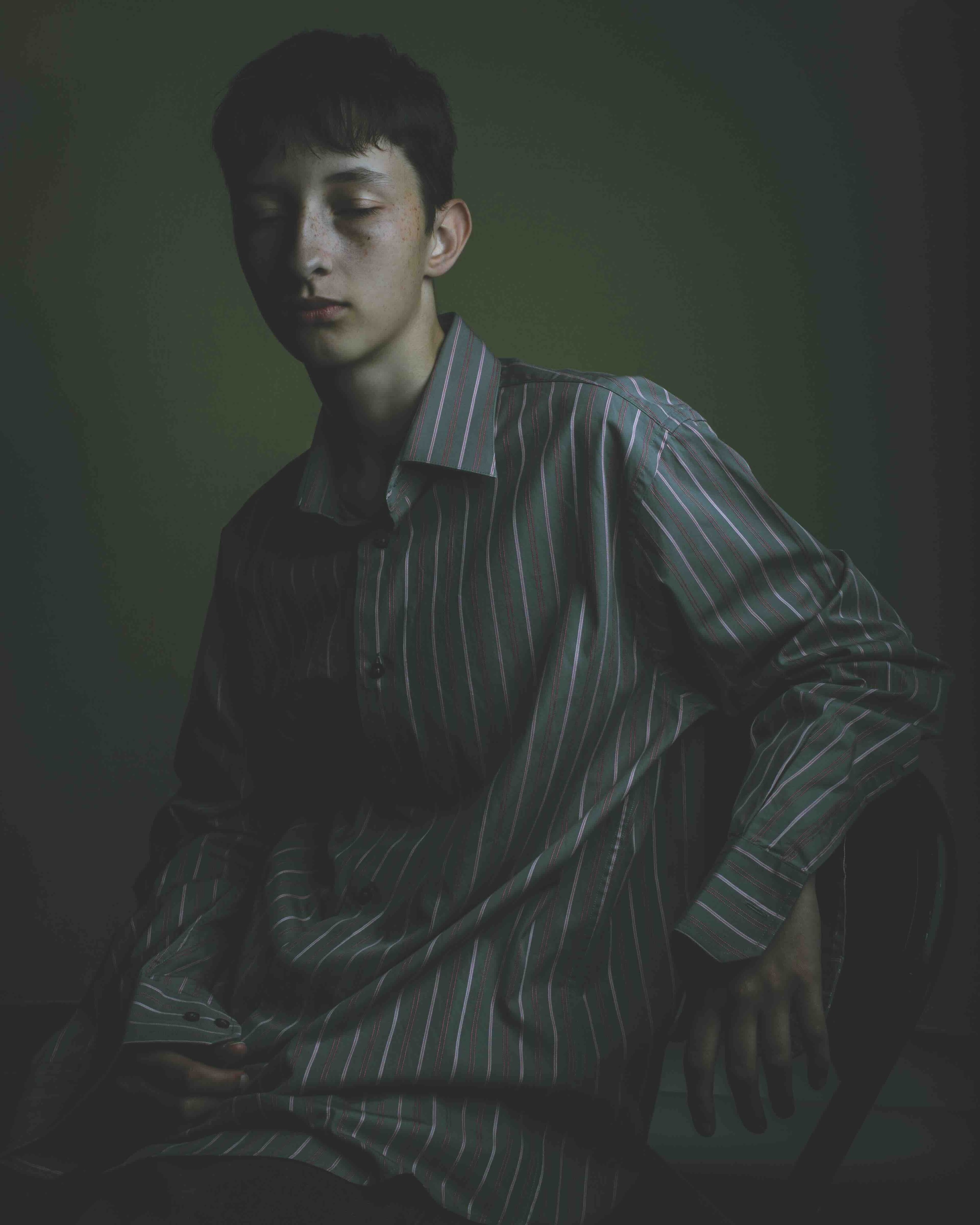

Swan was drawn to making portraits, and in particular to photographing people “over and over again” – siblings Toni, Nikita and Odin, who she met in a bowling alley, and Brody, who lived on her street. Hiring a boat club 10 minutes from her house, she would shoot them, and then their families, comfortable in a space that cost £10 to hire and that everyone knew was neutral territory. It was low-pressure, crafty, fun, there was “no ego about it”, she says; her subjects were there out of curiosity and for their own enjoyment, though she gave them the images. “That made it too, because I didn’t want to be cajoling someone into something they didn’t want to do,” she says. “It was experimental, working out ideas.”

Initially Swan used a borrowed camera and loaned 1960s studio lights; she eventually bought her own lighting kit, “a really rubbish home studio set” and, though she originally learnt to shoot on film, a simple digital camera. “It wasn’t about having technical knowledge or expensive kit,” she says. “It was about being able to make images quickly and cheaply, without any barriers.” Deciding to push further, she found an empty shop in Scarborough, on the North Yorkshire coast, that she could use as a makeshift studio. “I wanted to find a space that was more public and busier, that would allow me to do the same thing I had been doing [in Ramsgate] but in a much more intensive way,” she says. “It was quite a clinical place, 1990s depressed architecture; I found it a safe place to base myself, where people came by and used the loo or bought a birthday card. It was very calm and accessible, but busy and full of life. I was trying to create a moment where it’s like seeing someone in the street, but there’s this very formal environment around them. I wanted people to not have the chance to move or change themselves, but be in a studio setting.”

These portraits were successful and helped bring Swan wider attention; it is an approach she has returned to since, setting up temporary studios in shopping centres, train stations and London’s financial district. Working this way allows her to see public faces and hone in deeper, cutting out the visual noise of the street to focus on the individual. She is interested in how people’s bodies both conceal and expose their feelings and personalities, in the socially constructed gestures that allow us to conform, and the quirks that (sometimes involuntarily) mark us out. Swan’s gaze is comprehensive yet somehow not judgemental; something in her omniscience is warm.

“I want to see people,” she says. “The way someone is with their body is definitely something I pick up on, and then other things come out – all the good, hidden stuff. There’s a formality I really enjoy [in a portrait session] and there’s an attention that’s there from them. But I don’t want to ask them to come back next week. Then they’ll sort out their hair and face, they’ll get rid of all the things that they think are not OK, but which I find so beautiful.”

It is something she has managed to maintain in her commercial work, which also took off in 2021 when she was signed by London agency Mini Title. Commissioned for a Givenchy ad campaign, she maintained small ‘imperfections’ on the models’ legs, for example, which to her are not imperfect at all. “Someone said to me once, ‘Do her a favour, take the spot away [with retouching]’,” Swan says. “The concept of that I find quite hard to get my head around. Those signs of life are the centre of everything my work pivots around.”

This sensibility does not preclude post-production. For Swan, retouching is about directing attention, creating an interesting image rather than ‘perfecting’ a body, making blocks of colour to emphasise shapes or shadows, or creating an overall palette or feel. She is into early colour photography, Paul Outerbridge or Erwin Blumenfeld, though she adds that she discovered them later, and has always had her own sense of colour. Guy Bourdin seems an obvious touchpoint for some images but she is not enthused; the subjects in his work are models being fantasy-posed by a man, she says, and are presented in such a polished way. “What I prefer is the more human side, the less performative side,” she explains. “I’m rarely influenced by fashion photographers – Sally Mann, August Sander, Helmar Lerski, Alex Prager, Rineke Dijkstra, Gérard Schlosser, Roni Horn, William Mortensen are big influences.”

For Swan the apparently awkward is actively interesting, pointing towards the subject’s life, and what they do off- camera. When she shoots people in-studio in public places, she arranges it so they have some privacy, and therefore feel less self-conscious; she sometimes asks them to pose, but only because she is trying to help them relax. “Sometimes they’re so scared, you have to kind of let them into their body,” she says. For fashion photography and commissions she may have to exert more influence, but still prefers making suggestions to giving orders, and often just asks people to pause their own gestures. Even so, she says shooting commissions is very different to her personal work – the sitter has been chosen, and is often a model, there is a large team in the studio, a desired outcome, and very little time. But increasingly commissioners are coming to her because she includes that sense of the person, or even a slight sense of rawness, and these quirks are making it into the final images. “That’s always a win,” she says.

Swan’s outlook means she is as interested in hands, or legs – or any other part of the body – as she is in faces; for her, portraits do not have to show faces, and in fact she sometimes crops them out. “It’s just splitting up the body and letting those other parts speak,” she says. “There’s a level that’s enjoying taking away the ingredients of the face and having the poetry of the body and how that hand is, letting something else speak other than the eyes or the lips or the face.”

This is especially evident in Swan’s self-portraits, which she started making in 2020; they allow her to do “body work”, she says, without having to push someone else’s boundaries. And push someone’s boundaries they might, because they are often obliquely sexual, showing armpit stubble, or a nylon-clad crotch, or stretch marks. The idea of the ‘female gaze’ is often bandied around as if women see intrinsically differently – and although the idea is that women adopt a ‘male gaze’ in patriarchies – but perhaps there is something intrinsically female about Swan’s self-portraits, about the clash between her intimate knowledge of inhabiting a female body in 21st century Britain, and her in-depth understanding of photography. “I’ve never really said these photographs are self-portraits because I don’t even feel they are,” she explains. “It’s just a way of being able to use a female body without limits. To almost be the photographer and not be the subject.

“There is a grotesque element which feels slightly animal, which purposefully undermines the immediate perception it’s this shiny, sexy image. I’m reluctant to gender it too much, but I did feel like I was speaking to women, and that they would understand why. Seeing that armpit, or that stretch of skin, for women it feels like home rather than something that’s terribly out of the ordinary or difficult to look at.”

It is an insight that suggests something punky, and Swan loves the idea that her sitters – some of whom are now A-listers, contemporary icons of femininity – will see this work. But it also suggests another strand in her practice, which circles around looking at looking. Swan is well aware of the power of photography, and particularly portrait photography. She likes to shoot in-studio because her subjects know they are being photographed and can form a relationship with her, no matter how brief. She is uncomfortable with the idea of sneaking a photograph, with “snapping away when they’re not quite primed for it”.

Her images are also sometimes obliquely critical, often including a stereotype that queries this kind of photograph, why it is so prevalent, and what that says about our culture. It will be interesting to see how much irony she can maintain in her commercial work, but so far the balance is struck. “For years I thought I would just work by myself for the love of it – which was success to me,” she says. “But to realise that others are going to share in that intensity was really liberating.”

She is also continuing to push, recently making more work outside, exploring how landscape can exist in her practice, and shooting a series of shorts titled PLAYS. All three shorts focus on small moments, and particularly on body language; one shows a mother and child, physically close in the way that parents and young kids often are. The girl plays with her mother’s hair, puts her fingers in a hole in the woman’s tights; it is staged but they are a genuine mother and daughter, and that shows. Opposite this pair a couple passionately kiss, demonstrating another kind of physical intimacy – their embrace was also carefully staged, based on a 1950s, old Hollywood tryst, but so unrealistic and abstracted it becomes sexless and almost absurd. Swan wanted the kiss to be as a little girl might see it, she says, how she remembers (un)comprehending adult intimacy as a child.

Swan also continues to photograph herself, and Brody, the boy – or now young man – from her street in Ramsgate. These days he is studying in London, and Swan says their sessions are different but still compelling. “I have known him for a long time, and he is special to me,” she says. “He had a trust in someone who was quite random, and I just find his face incredible, and the way that he is so grounded and unbothered by things. I could take his picture forever.”