All images © Daniel Mebarek

Setting up a mobile studio in a Bolivian market, the photographer offered locals free portraits – Sergio Valenzuela-Escobedo speaks with him about collaboration, performance and the societal role of the itinerant photographer

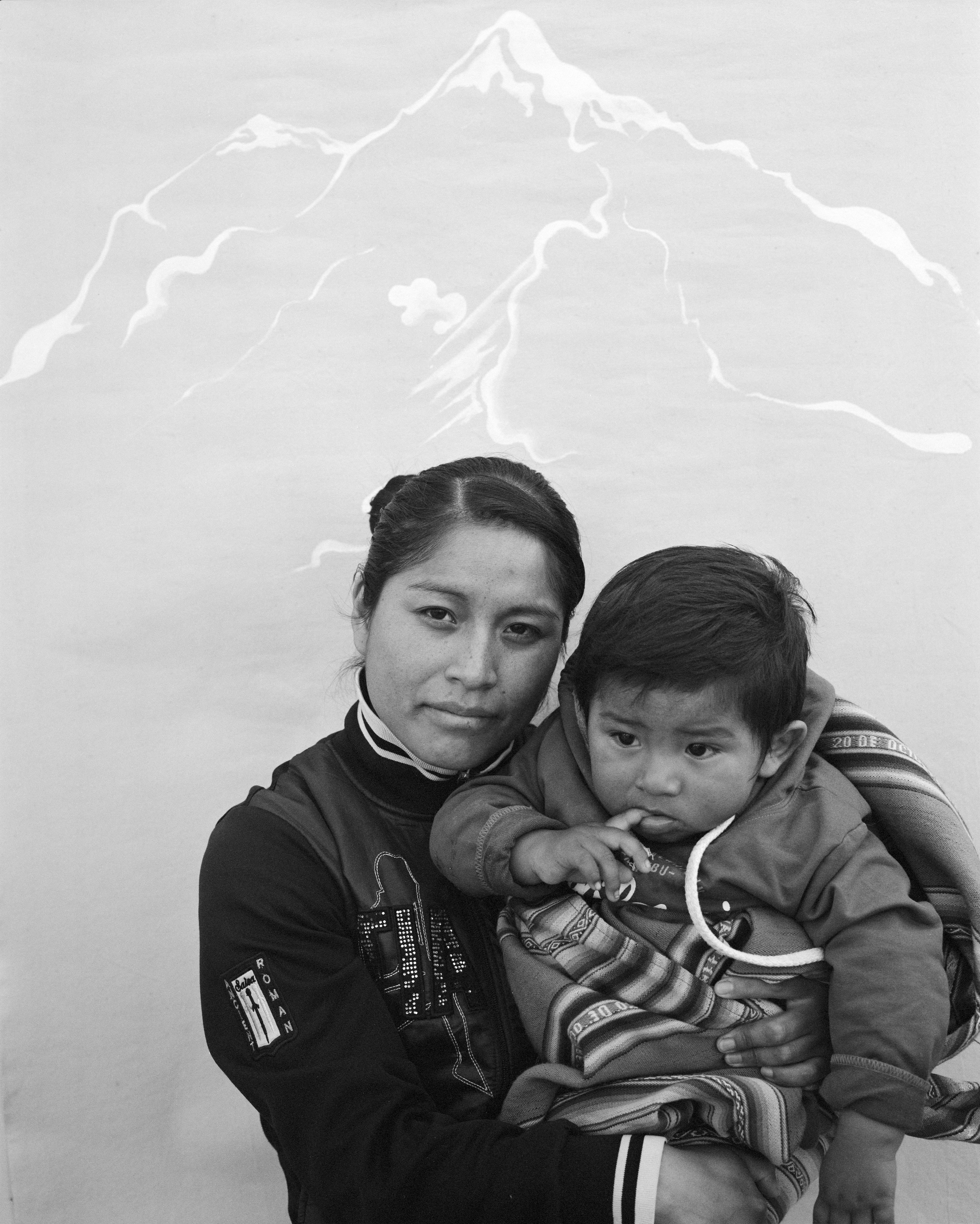

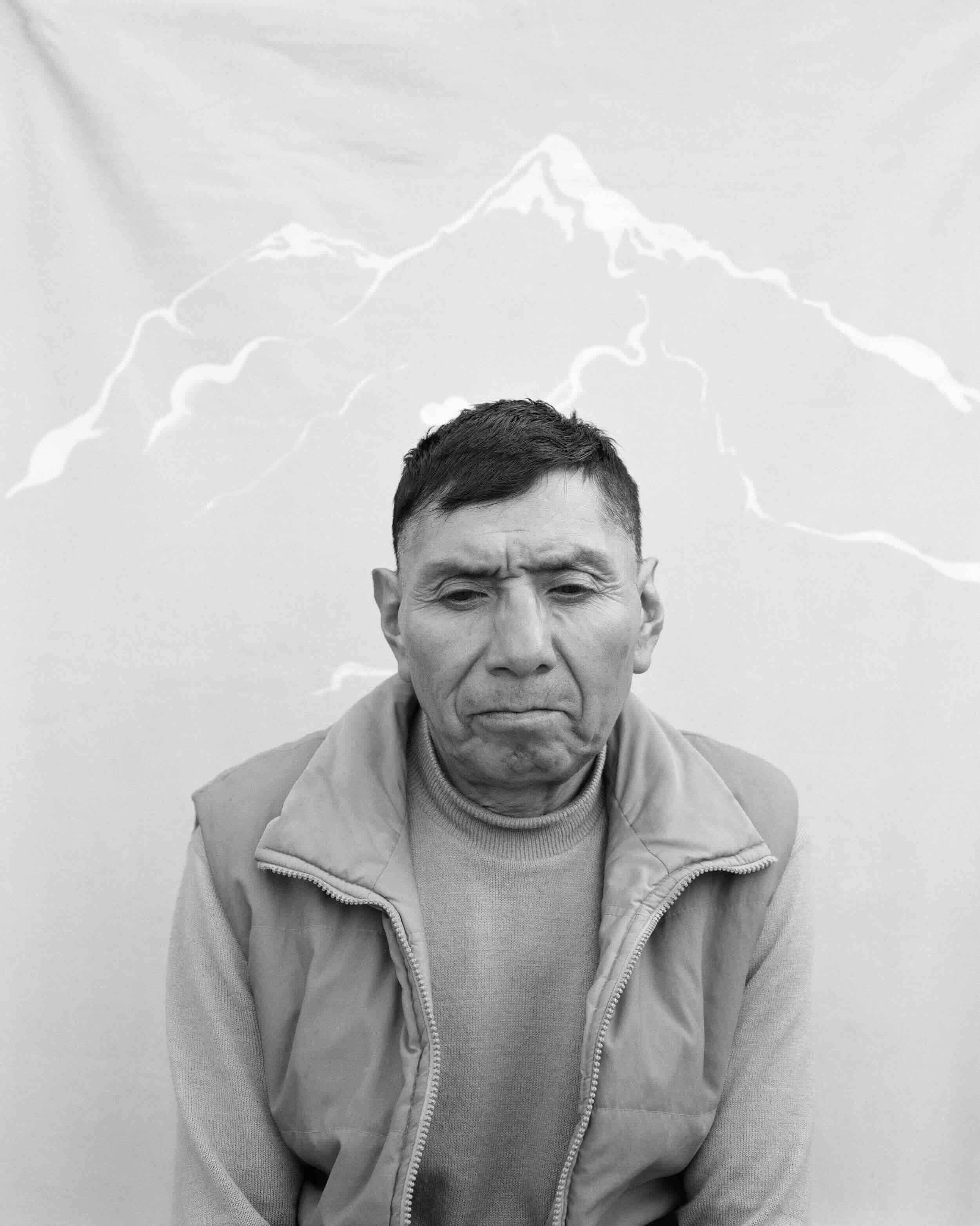

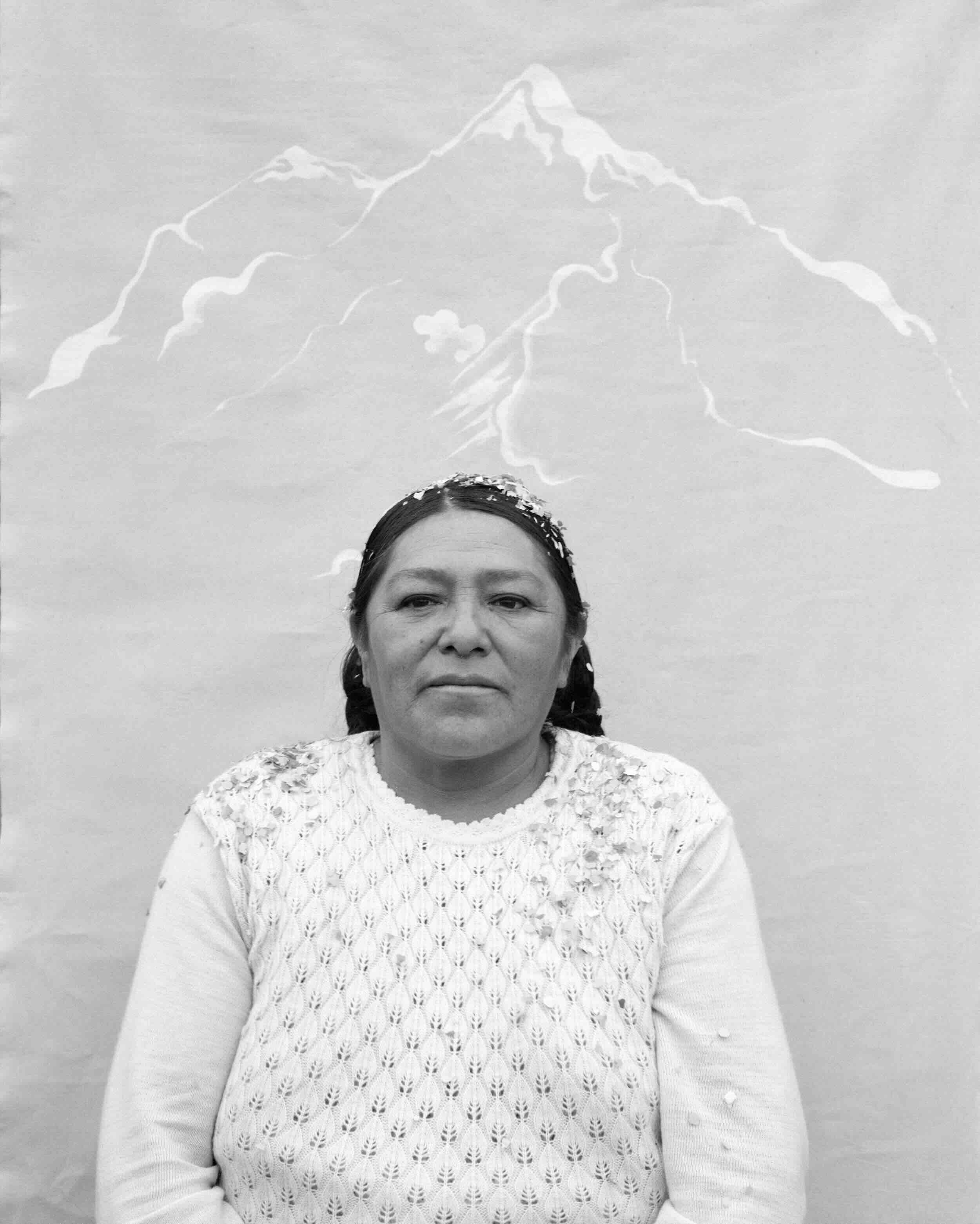

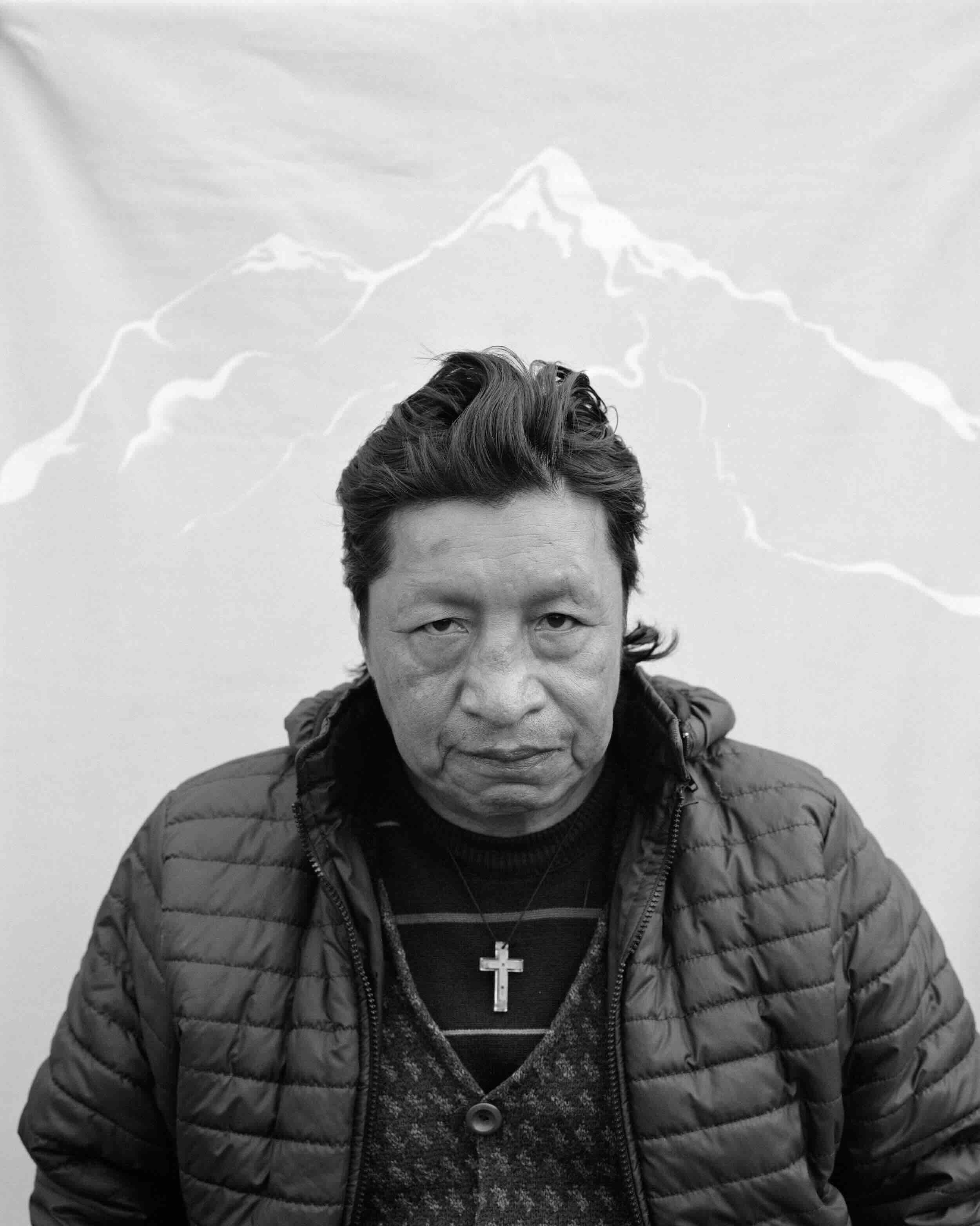

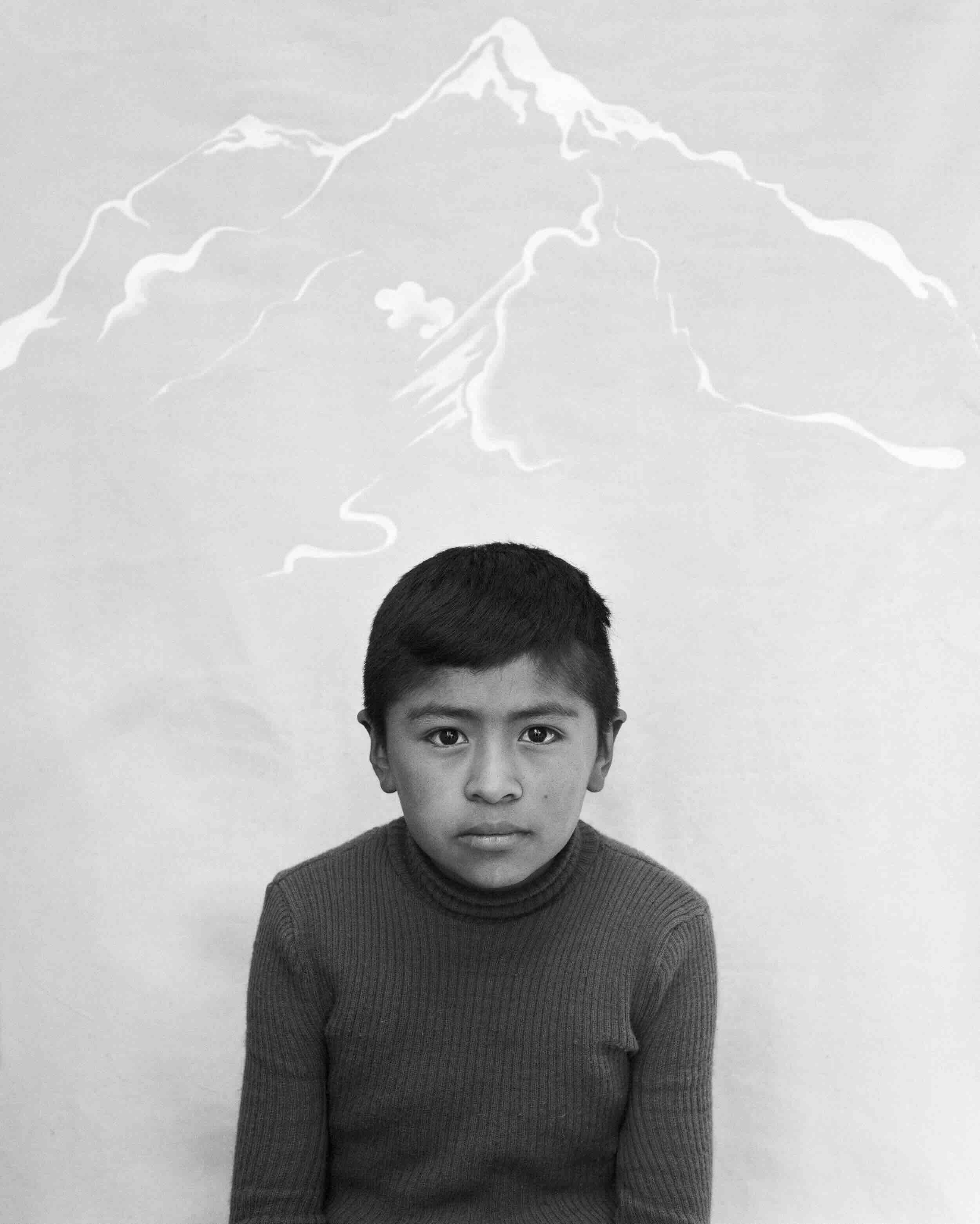

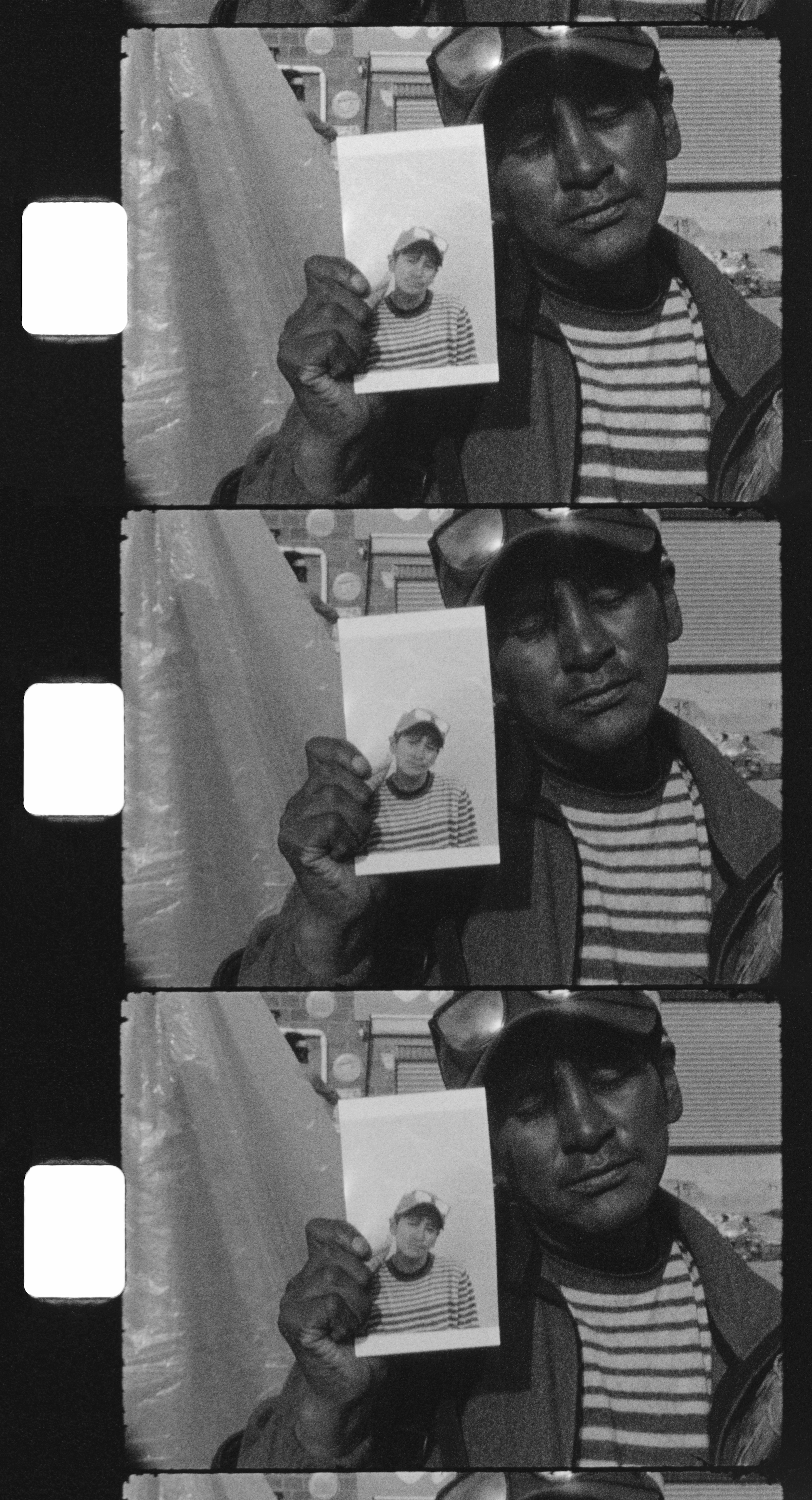

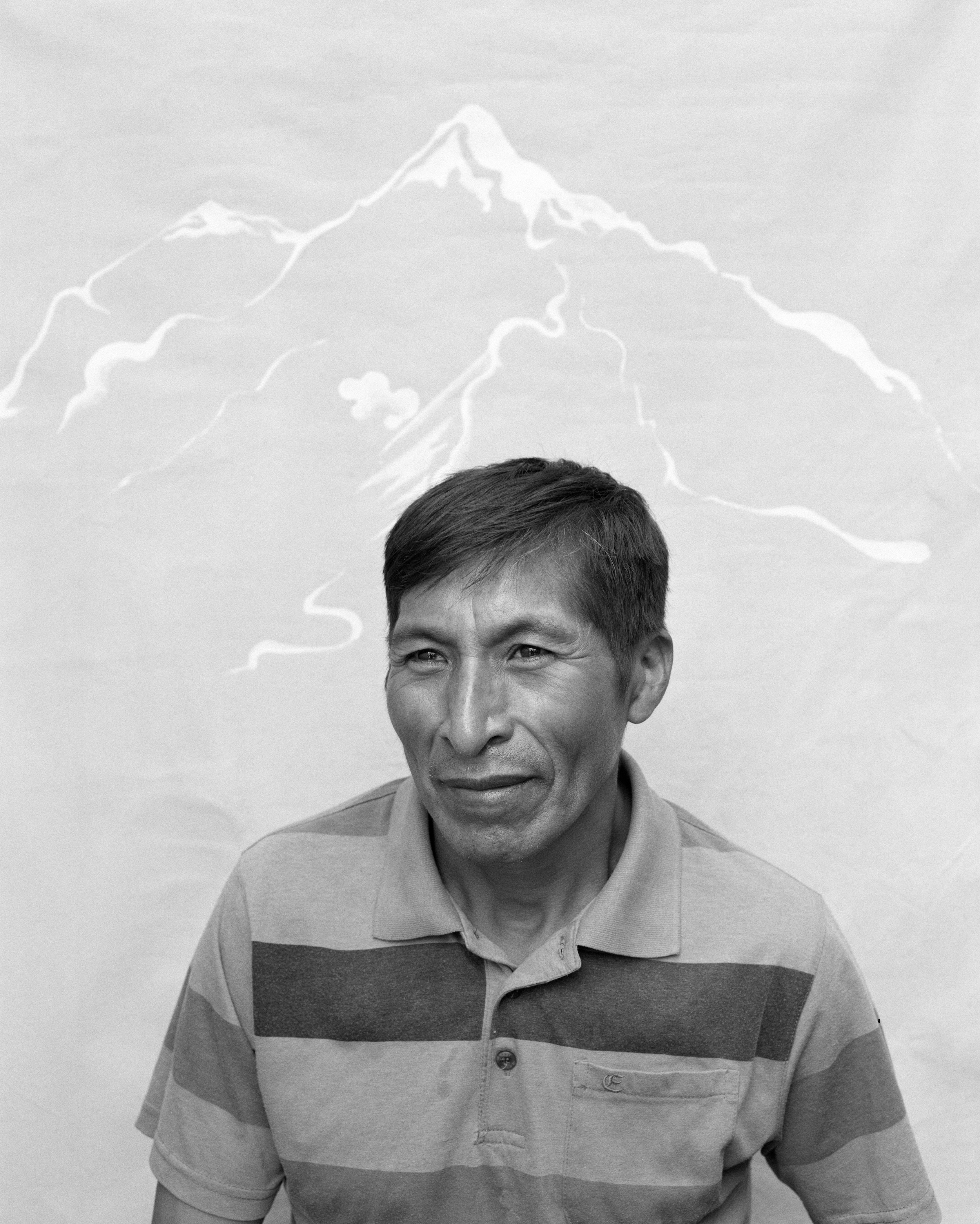

In 2022, Daniel Mebarek started his project Fotos Gratis, setting up a mobile studio to take portraits in the Feria 16 de Julio, El Alto, Bolivia, one of the largest street markets in South America. The studio includes a sign, stool, backdrop, tripod, cameras, megaphone and portable printer, and Mebarek, who was born in Bolivia but is now based in Paris, gives the portraits to the sitters for free. This project transforms him into a contemporary itinerant photographer, offering a unique perspective on the historical question of indigeneity. Mebarek is also documenting the project’s progress with a Super 8 camera, providing a poetic reflection of the complex dynamics of the photographic act.

Mebarek’s work is shaped by the gaze of both the photographer and the subject, and invites us to reflect on our self-perception in the act of being observed. As we begin to converse, I have two main questions in mind: how to represent alterity without burying it within the frameworks we carry, and how to address the symmetrical nature of the situation, am I myself the other of the other?

“Having lived abroad for many years, the mountain has come to symbolise my own nostalgic longing for the place where I grew up. This personal connection was also a reason why I chose this image as the backdrop”

SVE: The title of your project prompts me to reflect on the significance of the term ‘free’. Free for whom? What meaning are you attributing to this term? Are people surprised by the ‘Fotos Gratis’ sign?

DM: The title of the project plays on the meaning of the word ‘free’. While it’s true that participants leave with a ‘free’ photograph, I am also able to capture their portrait and, thus, get something in return. This give-and-take dynamic mirrors the concept of ‘ayni’, a principle deeply embedded in Andean culture, including in places such as El Alto. Ayni emphasises the importance of reciprocity in everyday life. Without romanticising the project’s process, my intention is to distance myself from an extractivist approach to image-making, and attempt to create another space around the photographic act.

The sign ‘Fotos Gratis’ also plays an important role in catching people’s attention. The style of this sign is commonly seen throughout the city, in public transport, stores, restaurants and among street merchants, including those at the Feria 16 de Julio. Most passers-by who encounter the sign find it amusing, though many approach with scepticism. Until the photograph emerges from the printer, there is a sense that everything could be just a fabrication. The proof is the photograph.

SVE: It’s compelling to shift perspective and explore the role of the ‘participants’ in the photographic act, namely the photographer who observes the subject, who in turn observes the photographer, while others watch them both. This approach helps us understand the complex relationships intertwined in the making of a photograph. How long have you overseen the studio, and what are some of the most memorable experiences you have had there? Who are the individuals depicted in the photographs?

DM: I have set up the photography studio on four occasions over the course of two trips to Bolivia, and I plan to continue the project. The goal is to create an open space for any passer-by who wants to have their photograph taken. As the sessions have progressed, I have noticed some patterns: many small children, brought by parents eager to capture a new memory; several middle-aged men who find amusement in being seen and participating in the project; and rarely any women on their own.

There have also been moments that have deeply touched and amazed me, such as when a mechanic, holding a political science book, invited me to his repair shop to discuss politics, or when a drunken participant thanked me for his photograph by later bringing me small pears. One particularly memorable moment was witnessing a man kiss his photograph and hold it to his chest as he walked away.

These stories are not exterior to the project but rather constitute a central element of it. I have always viewed this project as a performance, with both the participants and myself spontaneously playing roles. I am interested in this sense in how an artistic gesture in the public space can become an anecdote, a rumour and, in some cases, an urban myth. The work of Francis Alÿs, particularly his performance When Faith Moves Mountains [2002], has been an important inspiration for this aspect of the project. It is also the reason I consider the video documentation of it so important. The art lies in the process. The photographs themselves become almost just an excuse for certain interactions to take place.

SVE: Bolivia, shaped by mining since colonial times, now sees El Alto as the centre of Indigenous political struggle and cultural empowerment. The Aymara’s blending of traditional and modern elements challenges simplistic views of Indigenous identity, and the western extractivist way of life. Conscious of these complex realities within the continent, the critic Gerardo Mosquera has reflected that Latin American art has ceased to be ‘of’ and has instead become art ‘from’ Latin America. How does this reflection inspire your work?

DM: Mosquera’s reflection raises an important question on how artists position themselves in Latin America. He argues that we have become so insistent on showcasing our own identity that we fall into the trap of self-exoticisation. I try to bear this in mind as I work in Bolivia, a territory which continues today to be represented through clichés and stereotypes.

Two Bolivian thinkers, René Zavaleta Mercado and Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, have influenced my perspective on this matter. Their concepts of ‘sociedad abigarrada’ [Zavaleta] and ‘ch’ixi’ [Cusiquanqui] provide valuable insight on how identity in contemporary Bolivian society is shaped by the coexistence of multiple cultural differences. For instance, the person sitting before me might identify as Aymara and embrace local cosmologies, while simultaneously being fully engaged with globalised popular culture.

SVE: In your project, a backdrop featuring a painted representation of the Illimani by artist Kate Araoz is prominently displayed. The Illimani, a significant Andean peak visible from the city, has both geographical prominence and strong symbolic meaning. In Aymara culture, Mallku, or the Lord of Great Altitude, represents the summit and hierarchical authority. This deity, central to rituals such as the sacrifices of the Capacocha, is associated with sacred mountains which are seen as vital sources of life-giving water. The depiction of Illimani in the photography backdrop thus reflects both spiritual significance and the cultural landscape of El Alto. How do you perceive the influence of the Mallku in your own images?

DM: Bolivian poet Jaime Sáenz once wrote that the mountain is not something that is seen but rather “the mountain is a presence”, an energy that is felt in everyday life. When I decided to have the Illimani as the image for the backdrop, I was indeed thinking of its importance in local beliefs. I also thought about how the representation of the Illimani can be found everywhere there, from advertisements to paintings and television. It’s an iconic figure that I felt people would immediately relate to, and that could perhaps even contribute to creating a sense of pride and dignity as they sat under it for their photographic portraits.

At the same time, the Illimani is an inseparable part of the landscape of my childhood. Having lived abroad for many years, the mountain has come to symbolise my own nostalgic longing for the place where I grew up. This personal connection was also a reason why I chose this image as the backdrop.

SVE: When I see the landscape backdrops I’m reminded of the early 20th century, when anthropologists used early mobile cameras to photograph the Americas. Initially focused on urban settings and European-style societies, these photographs eventually included Indigenous peoples, with ‘neutral’ backdrops serving an ethnological purpose well into the 1950s. In your project, however, the backdrop doesn’t remain neutral. Instead we observe the folds and creases in the fabric and the clamps on each edge, drawing attention to the artificiality of the set-up. Given this, how do you view your role in the project when photographing individuals?

DM: While developing the project, I was interested in exploring the profession and societal role of the photographer. An important reference in this exploration has been the book Los Ambulantes [1984] by Ann Parker and Avon Neal, which documents itinerant photographers in Guatemala from an anthropological perspective. The photographs in the book beautifully capture various aspects of the itinerant photographer’s life along with the rituals and gestures sitters perform around the photographic moment, such as combing their hair, straightening their clothes, or sitting upright. My project’s video component highlights some of these gestures.

In Bolivia, photographers are often seen on the streets wearing cargo vests and carrying portable printers around their necks, covering events such as festivities, weddings and graduations. Photography is perceived primarily as a service, and this is exactly how I feel during the project – as a professional providing a service. I never feel more like a ‘photographer’ than during those times when I set up my photography stall for the project.

SVE: Itinerant photography, seen in the works of Ann Parker, Avon Neal, or Antonio Quintana in Yumbel, relied on landscape backdrops. They also displayed photos around their wooden camera to attract first-time clients. This not only shaped image production but also offered insight into the discourse of photographic exhibitions. Have you considered this in your project?

DM: I find this observation very interesting. In fact, the first time I set up the photography studio I decided to pin a sample photograph on the sign so people could see what the portraits would look like. This ties back to what I mentioned earlier on the importance of this photographic ‘proof’ for those unsure about participating.

Looking ahead, I also envision exhibiting prints of the portraits within the market itself. The goal is to return the images to the space where they were originally created, by setting up an exhibition stall on the street. I can also imagine including a sign that reads ‘Exposición de arte abierta’ [‘Open art exhibition’]. In this sense, I am interested in raising questions about the value of art exhibitions and their intended audience. I feel this would bring the project full circle.

SVE: It seems to me that this photographic ‘proof’ implies also a sort of social contract, whereby the photograph produced is of shared property. How do you see this question of ownership in your project?

DM: This question ties closely to the earlier discussion on the exchange aspect of the project. Each shoot produces two photographs: one taken with an analogue camera for the project, and another with a digital camera for the sitter. This leads to an intriguing scenario where neither I nor the sitters necessarily know where these images might end up. I often find myself thinking about the ‘lives’ of the photographs kept by the sitters – whether they are displayed on a wall, stuck on a fridge, framed on an altar, or perhaps forgotten in a drawer or box. Similarly, some sitters likely wonder the same thing about the photographs I keep.

This is also why I am interested in setting up an exhibition stall in the market and creating a meeting point or convergence between the ‘artistic’ photos I keep and the context in which they were produced.

SVE: When looking at your project, I am reminded of work by photographers such as Anthony Luvera and Federico Estol, who challenge the notion of the solitary genius by exploring the potential of photography as a collective and community-based practice. Recent publications such as Photography For Whom? [2019] and Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography [2023] have also highlighted this topic. How have these approaches influenced your work to date or future projects?

DM: The project has prompted me to reflect increasingly on the value of collaboration and participation in photography. I am particularly interested in how such strategies can broaden the discourse around ‘documentary photography’. This often involves, as you mention, artists becoming less preoccupied with their status as the sole authors of a project.

Recently I have also been questioning more deeply the role and place of the artist in society. I am curious about how an art project or action can foster meaningful social interactions among a group during the process, turning the artist into a ‘facilitator’ or in some cases an ‘educator’. Artist Pablo Helguera refers to these practices as “socially engaged art”. A notable example that I often revisit is Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ performance Touch Sanitation [1979–80], where she shook hands with 8500 sanitation workers of the New York Sanitation Department, saying, “Thank you for keeping New York City alive”. The art was in all the interactions taking place, in the conversations and the sharing of different stories. This is one direction I would like to move towards, dedicating part of my practice to projects where the artistic value lies in the process itself rather than in the finished product.