All images from Akram Zaatari: Objects of Study: Hashem el Madani/Studio Practices, 2004–2007 and Footnotes, 2018. Photographs by Hashem el Madani, Saida, 1950s–70s © Akram Zaatari. Courtesy of the AIF/Beirut.

Opened by Hashem El Madani in 1953 in Saida, the studio documented many sides of the Lebanese community, a legacy that Akram Zaatari is on a mission to preserve

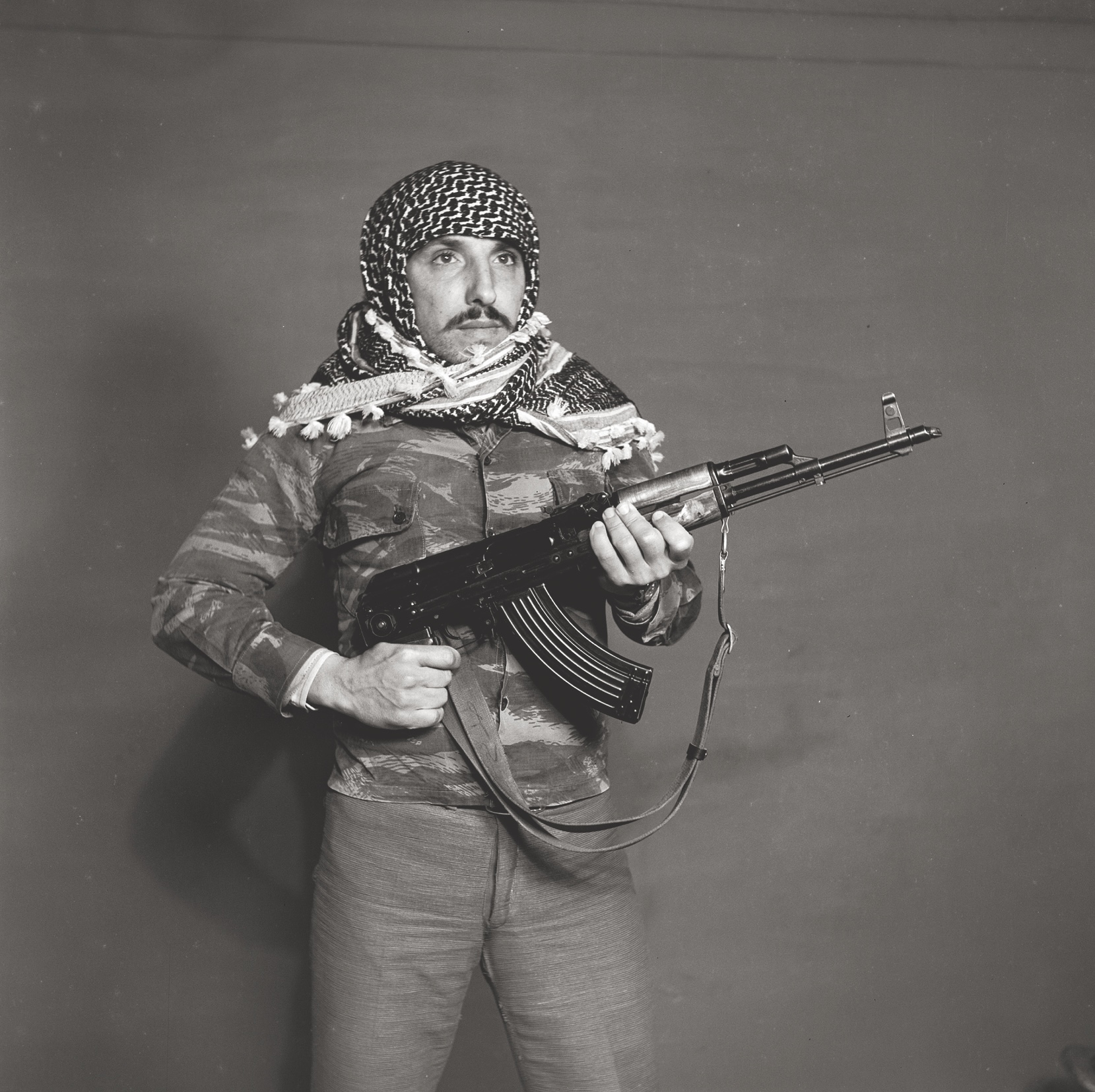

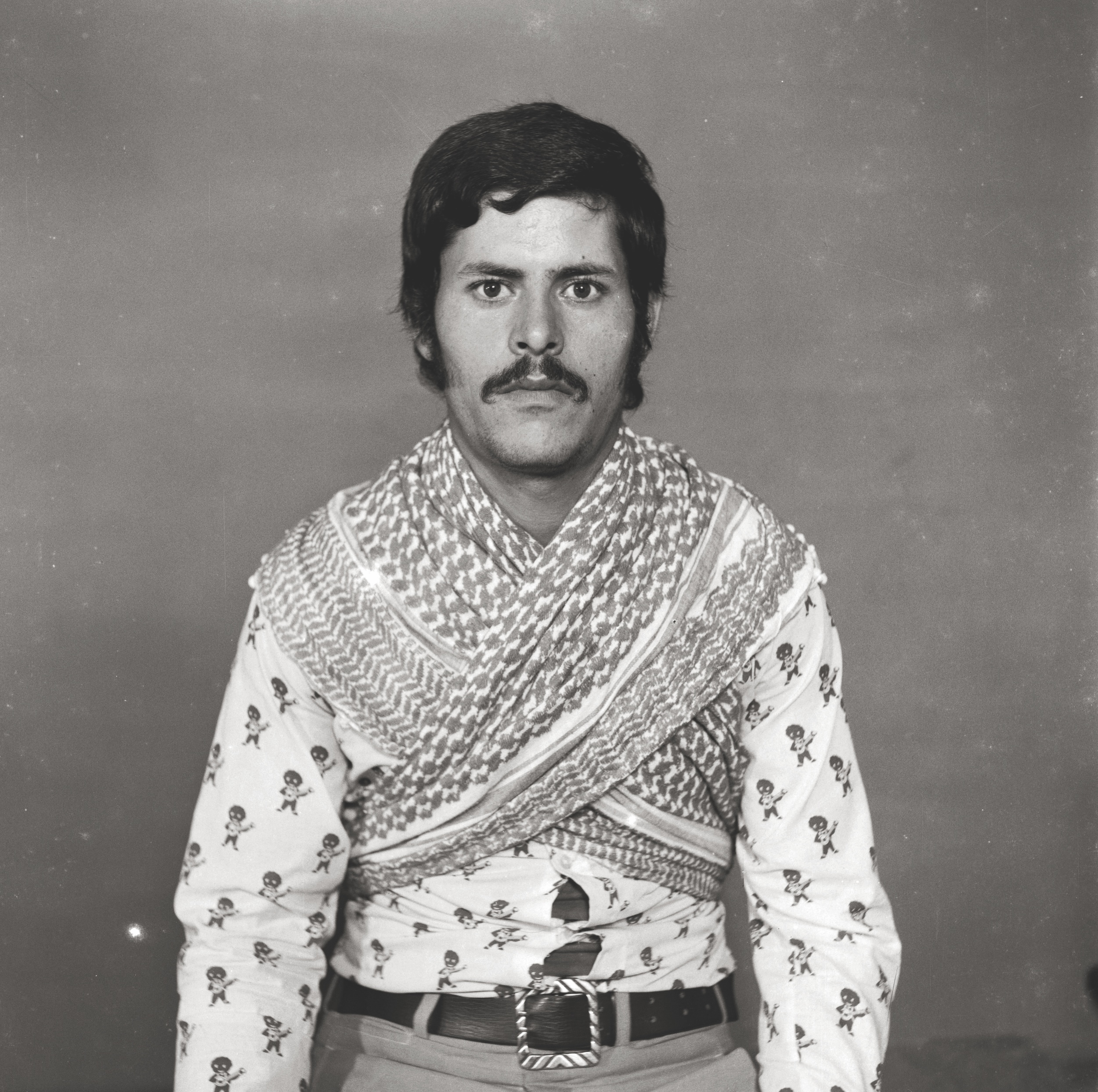

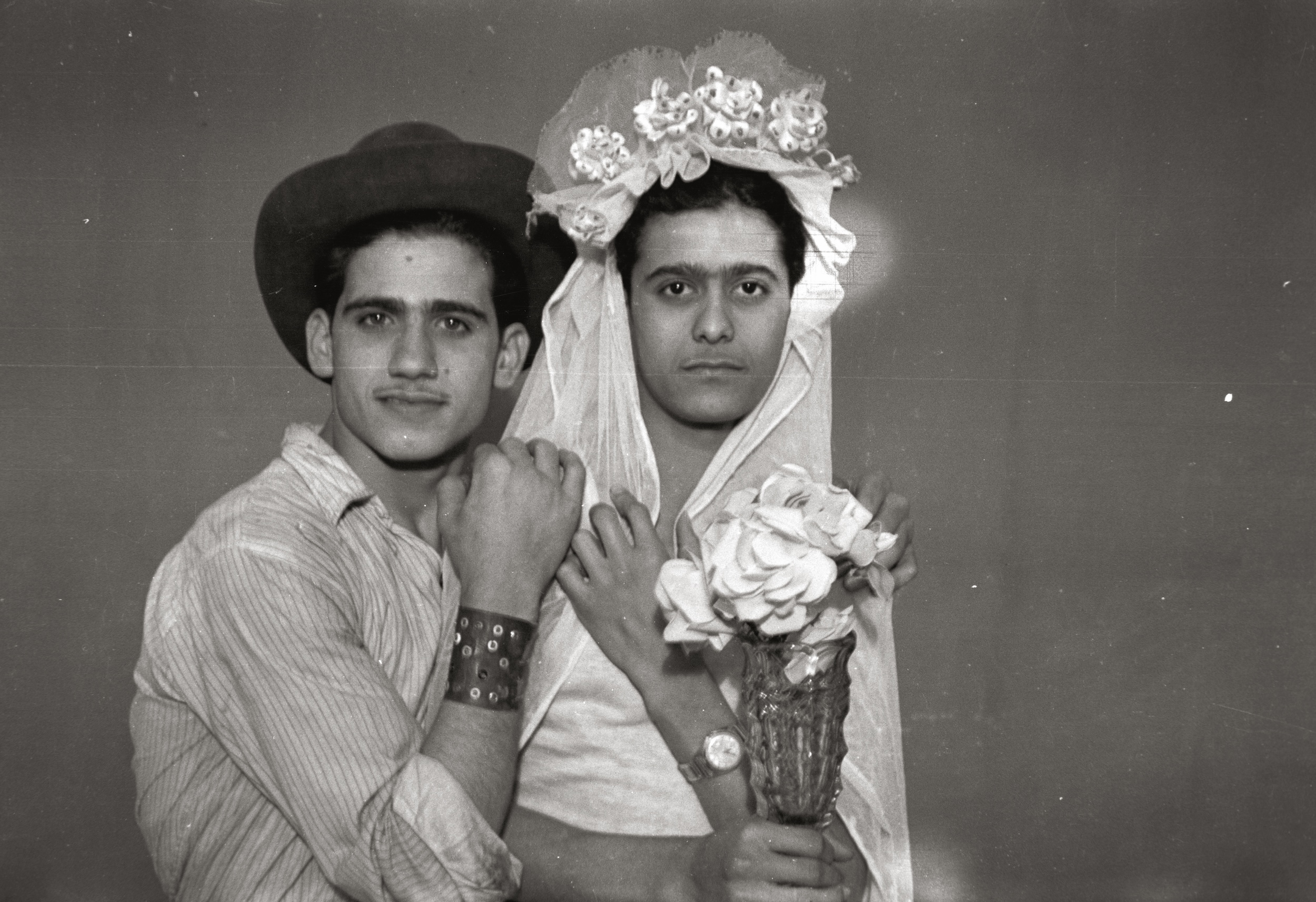

Lebanon, 1950s. Two young men imitate a newly-wed couple. A young woman wears sunglasses and holds her bike, moving towards the camera. A resistance fighter poses with his gun, gazing up and out of the frame. On the Arab side of social media, images from and references to Studio Shehrazade have filled timelines and platform pages for years. Never intended to encompass a wider imagination of Arab visual culture, these images have nevertheless become central to the conversation around photography in the SWANA region.

Born in 1928, Hashem El Madani began photographing his hometown Saida’s inhabitants in 1949, from his parents’ house in the old city. His services were advertised in the grocery shop nearby. Later, when Madani had raised enough money to open his first studio in 1953, he moved to the first floor of a commercial building, named Shehrazade. Subjects were liberated from being under the watchful eye of Madani’s parents, free to pose as they chose, but they were mostly inspired by what they watched in the cinema; Egyptian and foreign films, love stories, dramas, suspense and comedies. Studio Shehrazade peaked in popularity in the 1960s and 70s, when Madani took up to 100 portraits a day and, according to his own estimates, he photographed 90 per cent of Saida’s population.

Akram Zaatari is a Lebanese artist also from Saida (the city takes its name from the Arabic word for ‘fishing’, owing to its historic fishing industry) who co-founded the Arab Image Foundation (AIF) in 1997 with Fouad El Koury and Samer Mohdad. Since 2017 he is no longer associated with the foundation but he continues to publish and work on the outcome of his research (1997–2002) preserved at the AIF. The book Studio Practices accompanied Zaatari’s first exhibition of Madani’s work at The Photographers’ Gallery in London in 2004. It was co-published by The Photographers’ Gallery, Mind the Gap and the AIF, revealing and exploring Madani’s work on a large scale for the first time, taking the images from the sidelines of history to a major body of work.

“These photos would be seen as a solution that tricked the forbidden to illustrate the kiss, enabling its figuration by staying in line with social norms”

Zaatari met Madani in 1999 through a mutual friend when Zaatari was working on an exhibition and book for the AIF, The Vehicle: Picturing Moments of Transition in a Modernising Society, which retraces signs of modernity in photographs. Upon entering Madani’s studio, Zaatari realised the older photographer had amassed around half a million images, taken from 1949, through the opening of Studio Shehrazade in 1953 and up to the early 80s, using various formats and cameras. “I could see how he was learning and advancing and could see his mistakes in the early days,” Zaatari tells me. He made audio and video interviews with Madani extensively between 2000 and 2008; the entire fieldwork extended from 1999 until the last scene Zaatari filmed in Madani’s studio in December 2013, while making the film about the photographer, Twenty-Eight Nights and a Poem.

Although the scenes in Madani’s images are confined to the studio, they sometimes echo the environment outside, with now widely popularised images of Syrian and Palestinian resistance fighters in traditional dress wielding guns. In some images, men imitate scenes of violence with fake knives, fake guns, and expressions of what look like stage-fright. The 1970s and 80s were a period of upheaval not dissimilar to today’s Lebanon – while writing this article, I am unable to speak with Zaatari due to the Israeli invasion, and we must conduct the interview through email.

During the Lebanese Civil War from 1975 to 1990, Israel invaded the country in 1978 and again in 1982, and Saida saw much of the fighting, owing to its seafront location and proximity to both Israel and the Lebanese capital, Beirut. Even so, Madani’s images have a pervading sense of playfulness. In them, one finds both a nation witnessing violence, and a people with an ineffable sense of humour. In one setup, two maids sit shoulder-to-shoulder with large glamorous sunglasses, as if celebrities caught in public by the press.

Since Zaatari’s artistic intervention in the work, Studio Shehrazade has become an institution. Madani’s images have been celebrated throughout the Arab world and its diaspora. The emphasis here is on the diaspora – the second generation, removed from their ancestral homelands, who have relied on the archives to engender a sense of belonging, collective history and identity. Studio Shehrazade has acted as the entrypoint for young Arabs around the world to connect to a vision of themselves as seen by their own, as opposed to outsiders’ often inaccurate representations.

In 1999, Zaatari worked with Madani as a documentary artist collecting details about the practice. He secured the conservation of Madani’s negatives through the Arab Image Foundation and transported a large percentage of them to be conserved at the AIF in Beirut. The AIF also managed the circulation of the projects made by Zaatari and paid Madani royalties twice a year. “Around the year 2000, I decided to have an archeological approach to research this collection, and gradually I announced the studio as a site of an ongoing excavation that aimed to study a photographer’s practice, but also his ties to people in his city and work on reanimating his dying economy,” Zaatari explains.

The task required bridging the gap in technology, which meant digitising images so Zaatari could work with them. “It’s where the Arab Image Foundation played a significant role by accepting to host the Madani collection, and gradually scanning my selections from negatives, which amounted to almost 30 per cent,” says the artist. The Prince Claus Fund (Netherlands) helped enormously in this.

Five years later, when Zaatari had a gallery, he and the AIF decided to put editions of the work on sale, signing a three- way agreement with Madani for Zaatari’s Objects of Study/ The Archive of Studio Shehrazade project. In 2016, a year before Madani died, Zaatari agreed with him and the AIF to acquire his copyrights, and today remains the copyright holder.

Interestingly, Zaatari insists that the studio remained local and that, at least during his active years, Madani did not circulate his images widely. “We are talking about a local photo studio, the photos of which were mostly printed on inexpensive 6×10cm paper that mainly stayed with their people. Madani was known in Saida… but not elsewhere,” he points out. That does not at all reduce his significance today, Zaatari stresses. Madani trusted Zaatari with his work “entirely”.

“His business had reached a dead end when I met him in 1999,” says Zaatari. “He would go to his studio and sit all day without any customer knocking at his door… The question for me remains, how to wrap up a practice that spanned 69 years. This is my mission.”

The legacy of Studio Shehrazade therefore comes mostly posthumously, through Zaatari’s ‘archaeological’ and documentary intervention. It also owes something to its accidental queer liberatory visual language. It is hard to find queer imagery from the SWANA region, even more so from the 20th century, so Madani’s images of same-sex kisses have been reappropriated. Yet they have never been what they appear. “Neither kissing between individuals of the same sex, nor the circulation of its photographic documentation later, would be interpreted as an affirmation or celebration of homosexuality in Saida during the 1950s,” affirms Zaatari. “These photos would be seen as a solution that tricked the forbidden to illustrate the kiss, enabling its figuration by staying in line with social norms.”

In other words, it is hard even by today’s standards to visually depict physical intimacy in the Arab world; ironically, queerly coded visuals are a loophole for the depiction of romance. “Kissing would alternatively be performed between friends of the same sex,” says Zaatari. “Men would kiss men, and women would kiss women.”

Lebanon was also at the height of Arab ‘cool’ during the 20th century, despite its period of war. The country was at the forefront of the SWANA world’s interaction with globalised visual media during this time and – with its generally more ‘liberal’ approach to nightlife, music and style – was arguably the first to introduce European fashion and living aesthetics to the Middle East. “I had to make a comparative assessment to understand exactly the changes that photography brought to society, promoting fashion and a mode of living that leaked easily from one culture to another thanks to photographs and films, and the changes society brought to pictures,” Zaatari says of his own motivation to work with Madani.

“So, part of my interest was in documentation. In general, the life of a photo studio is very similar everywhere in the early-to-mid 20th century,” he adds. “The smell of a photo studio is the same everywhere as well, due to the chemicals used in it. And I loved that smell!”

As an artist and documentarian, Zaatari is fascinated by the ways in which these studios differ also, especially around their size and location, since some places attracted far more work than others, such as Jerusalem or Cairo, “both so heavily visited and fantasised about,” Zaatari tells me. A studio’s clientele, whether local or transient, is key. “My main interest in Madani’s profile was that he dedicated himself to a local working-class clientele, and he built his network closely with his subjects so he became, in a way, their magician,” he says.

In one image, we see a woman with her face scratched out. She was Mrs Baqari, whose jealous husband admonished the photographer for taking pictures of his wife without his knowledge. Mr Baqari insisted the photographer scratch the negatives, so that they became useless in the future. Tragically Mrs Baqari later burned herself to death, after which her husband asked for these damaged images to be printed for him to keep.

Working with the archive is not straightforward. “The question of authorship remains the most essential to me while working on someone else’s images, taken sometimes before I was born,” Zaatari says. “It was essential for me and for the AIF to understand that we are complicating captioning, for example, not because we like complexity, but because authorship is not simple – especially in photography, where the person who clicks the button is the author.”

Zaatari stresses that his work on Madani is not a collaboration with the photographer, but rather an artist’s documentary project that addresses the practice of a local photographer. “It’s like making a film about an artist,” he explains. “This is an artwork about a photographer and his images. So, we had to live with two names, mine and his, two dates, the taking of the photo and the making of the project.”

Currently, Zaatari is working on developing a large cabinet that would represent the life of Studio Shehrazade, including cameras, flashes, photos, postcards, AV material representing scenes from the studio, parts of his interviews, films, and so on. The Madani project runs parallel to Zaatari’s other work; both he and the AIF were heavily impacted by Lebanon’s economic collapse in 2019, and they are still slowly recovering.

Zaatari is currently researching material made by Madani’s brother Hussein, who was a few years older but worked for him as an itinerant photographer in the 1950s and early 70s. “Hussein was a marginal character, who worked only to cover his debts,” says Zaatari, adding that the older brother was sadly run over and killed in Beirut in 1973. He left a substantial number of 35mm film negatives of youngsters, leaving movie theatres after watching Bruce Lee films and practising martial arts. “I plan to work with this material as well soon.”