Dee Dwyer on the importance of true historical representation

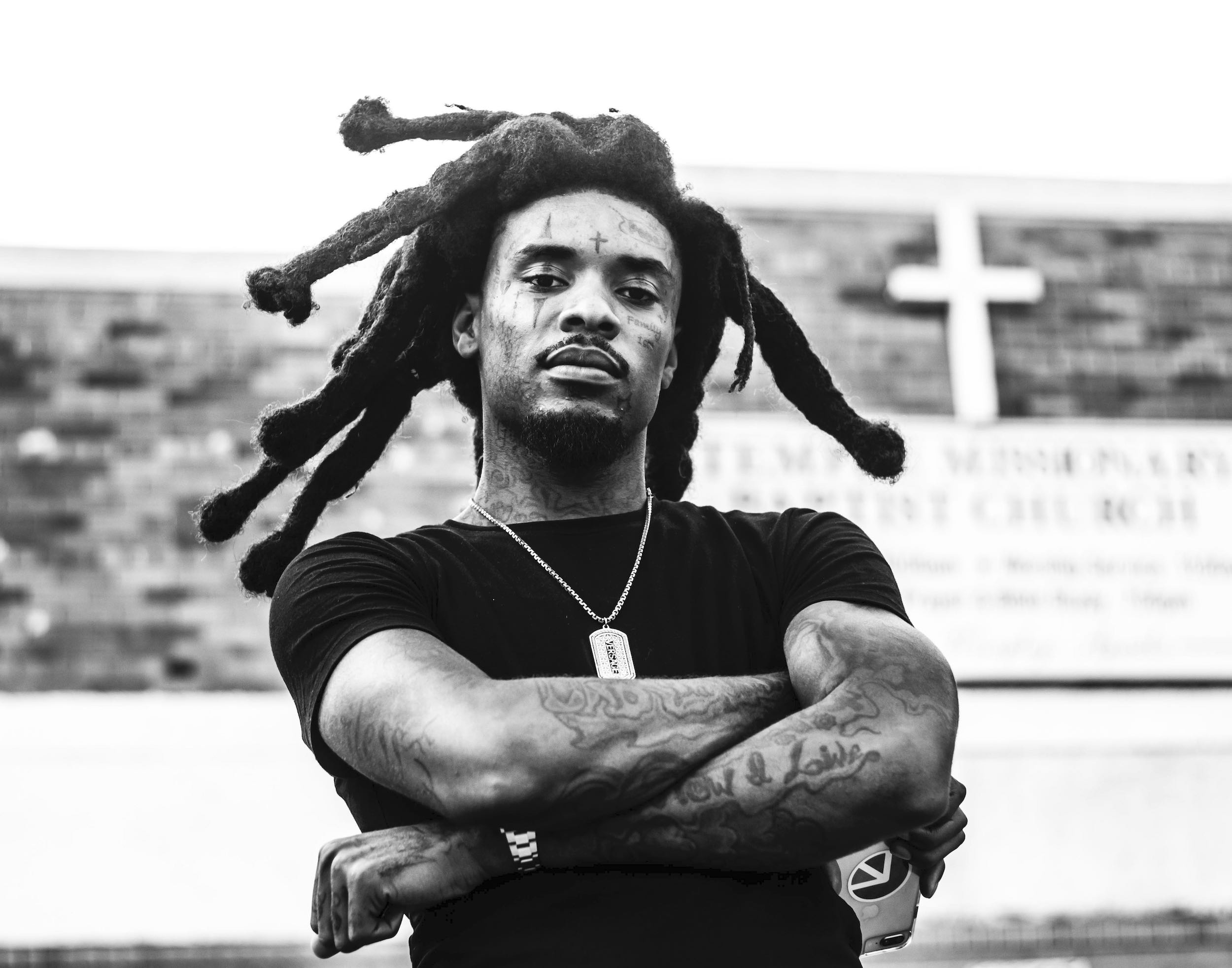

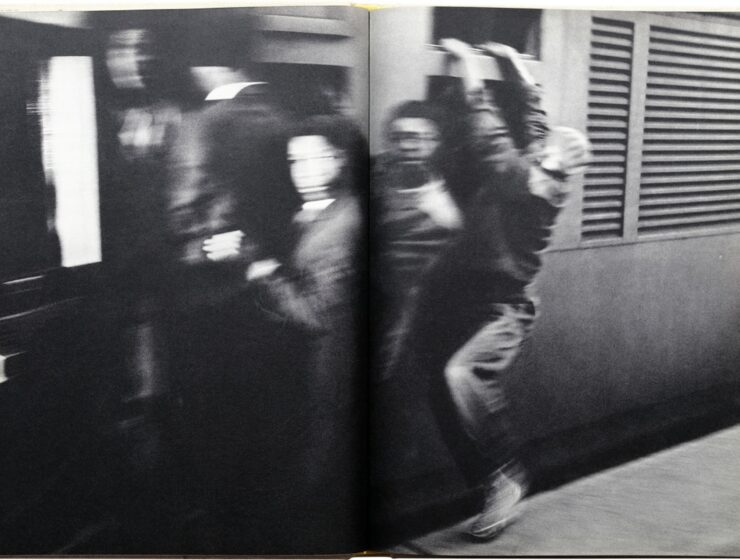

D.C. Protest June 7, 2020 at Black Lives Matter Plaza after the death of Geroge Floyd and many others who'd lost their life and or were unfairly treated by the government system. This man was telling protestors to stand up after he realized that lying on the ground for a demonstration did not show dignity. He states this is how the government wants us t be. Lying down we will stand up and rise. © Dee Dwyer.

Source: