For the past half decade, Dee Dwyer has documented the ongoing protests occurring in her city, Washington DC, feeling it her duty to tell the story from the perspective of the Black community.

For the past half decade, Dee Dwyer has documented the ongoing protests occurring in her city, Washington DC, feeling it her duty to tell the story from the perspective of the Black community.

A year of job cuts and financial turmoil in the creative industries has unmasked fundamental issues of inequality, rooted within the system long before the pandemic. We ask, what can they do better?

Futures, a platform dedicated to emerging photographers, returns to Unseen this year with another crop…

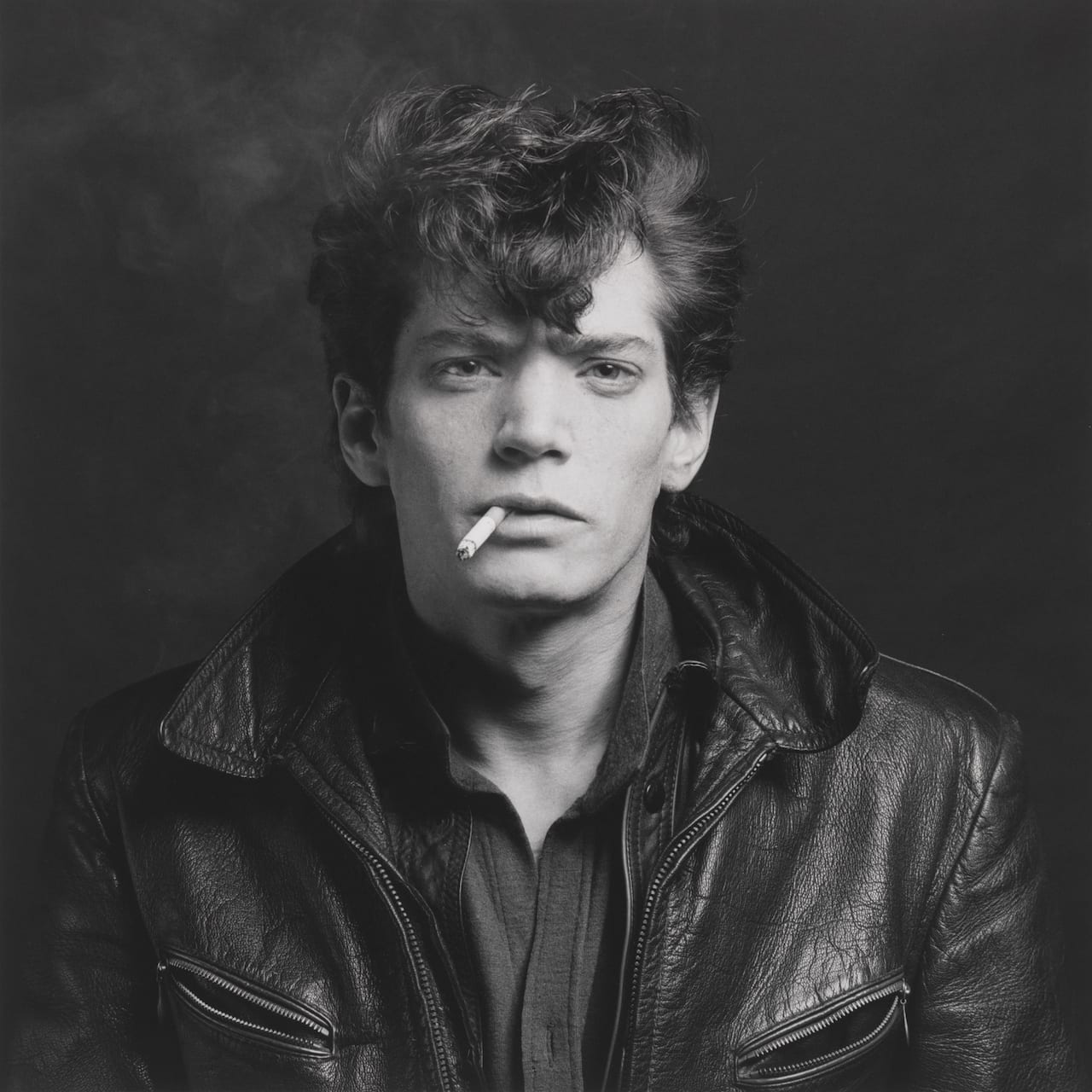

In the winter of 1988, at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, an exhibition opened, triggering outrage. The Perfect Moment, a display of 125 photographs by New Yorker Robert Mapplethorpe, was the most comprehensive show of his work to date – and the most provocative – featuring images he had taken over the previous 25 years, including those of his divisive X Portfolio.

The retrospective came at a difficult time in Mapplethorpe’s life: he was 42, and losing his fight with Aids – the disease that would take his life the following March. Perhaps, for him, this was his final chance to show this expansive oeuvre to the public – most of it shot in his Manhattan loft. But his pristine black-and-white photographs of BDSM scenes, and the sexy, sinewy strangers he met at the Mineshaft sex club, shocked conservative audiences. On a political level, the culture wars in the US were raging.

Behind a shop vitrine, a human skull, wearing a helmet adorned with a swastika, grins. Next to it, an animal – apparently taxidermic – stands rigid on the floor. The silhouette of a pair of legs belonging to a passer-by on the street reflects in the glass. Above this desultory display, a banner stuck to the top of the window reads, “Mexico… ¡quiero conocerte!”. In this single photograph, taken in 1975 in Chiapas, Graciela Iturbide projects her vision of Mexico: a country of political, religious, social, cultural and economic pluralities and tensions. A place where contrasts present themselves at every turn – sometimes harmonious, sometimes tense.

It is this multilayered image of Mexico that Iturbide has slowly peeled back and revealed through her photography over the last five decades. She has travelled extensively across her own country, between urban and rural landscapes, living with different communities, and moving from the physical to the transcendental, the ancient to the contemporary, witnessing and experiencing the juxtapositions intertwined in Mexican culture.

The paradox of otherness is at the core of Maria Sturm’s You don’t look Native to me. Her subjects belong to the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, the largest tribe in the region with around 55,000 members, with their name taken from the Lumber River of Robeson County. Starting in 2011, Romania-born, Germany-raised Sturm spent time in Pembroke, the economic, cultural and political centre of the tribe, photographing their daily lives. It opened up questions about visibility, identity and stereotype in the US, where Native Americans are romanticised yet often dismissed. Many tribes remain officially unrecognised, though the sense of identity within the communities is very strong.

On her first visit, Sturm was struck by two aspects. “One was that almost everyone I talked to introduced themselves with their names and their tribe. The other was the omnipresence of Native American symbolism: on street signs, pictures on walls, on cars, on shirts and as tattoos.” She attended powwows (where leaders pray to Jesus, another surprise to Sturm) and spent time with locals.

“In the EU today, we take women’s rights for granted,” says Marina Paulenka, director of Organ Vida, a three-week international photography event held annually in Zagreb. Founded in 2008, the festival has always been driven by political context, and this year, for its 10th edition, its all-female team have chosen to emphasise female-identifying perspectives from around the globe.

“In a time of post-capitalist global turmoil, technological advancements, with the strengthening of rightwing extremism, the growing influence of religion that limits women’s rights again, and the semblance of democracy in the 21st century, we are facing a situation in which women must fight anew for the rights that had been won long ago,” Paulenka insists.

“The new interest in street photography over the last decade and a half is perhaps the single biggest global movement photography has seen in its 170-year history,” says Nick Turpin, creative director of Street London, the third annual edition of the festival dedicated to street photography, taking place at D&AD’s new east London space from 17 to 19 August.

The three-day event, hosted by Hoxton Mini Press, includes guest speakers, shoots, panel talks and, of course, a street party on the Saturday night. There is also an opportunity for photographers to pitch for a 10-minute slot on stage, the Spotlight sessions, where 12 successful applicants will present their projects to an audience for constructive feedback. The theme for discussion this year revolves around how street photography is being redefined by photographers who have emerged from other backgrounds, including photojournalism, art photography and portraiture and how this has influenced them today. There is also a conscious view to look to contemporary expressions of genre.

Between 1960 and 1997, the idyllic Italian island of Sardinia witnessed a series of kidnappings at the hands of the anonima sequestri sarda – a group of vigilantes meting out justice according to a traditional, local code of honour known as the codice barbaricino. Over 37 years, 162 people were kidnapped for ransom, with some of them killed. The kidnapping of seven-year-old Farouk Kassam in 1992 is particularly vivid for Sardinian-born-and-raised Valeria Cherchi, who was the same age at the time. The case instilled in her a profound fear. “I clearly remember the news, during his fifth month of imprisonment, that the upper part of his ear was found by a priest on a mountainous road in Barbagia, central Sardinia,” she recalls.