Past performance

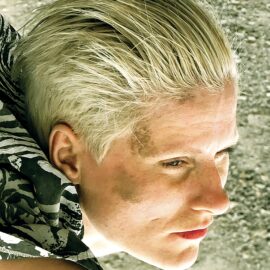

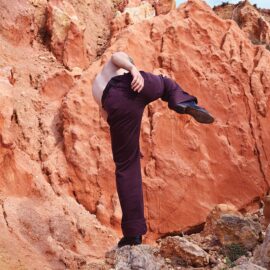

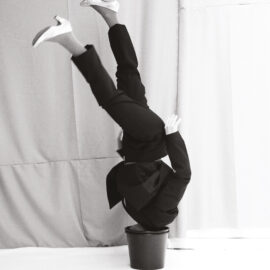

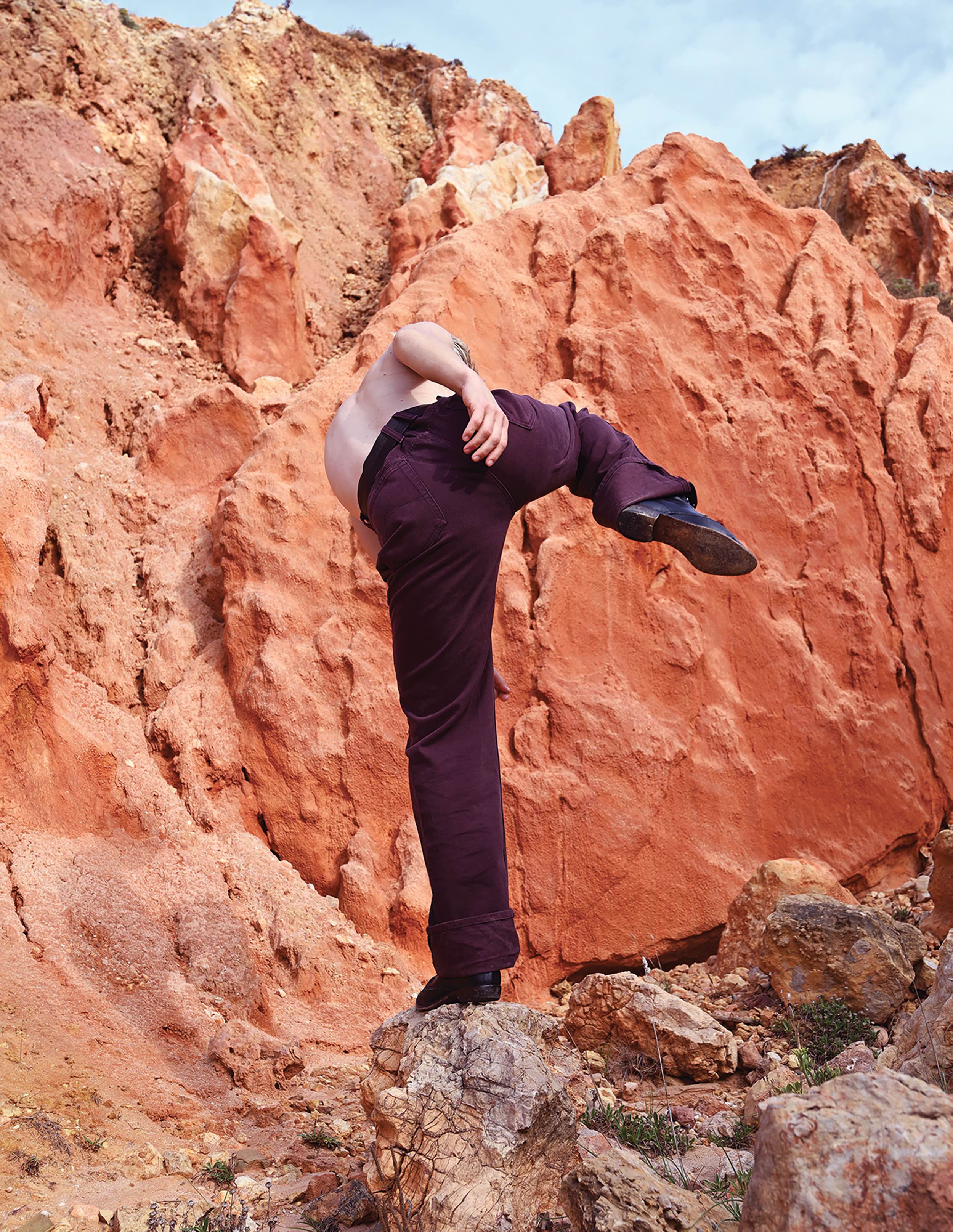

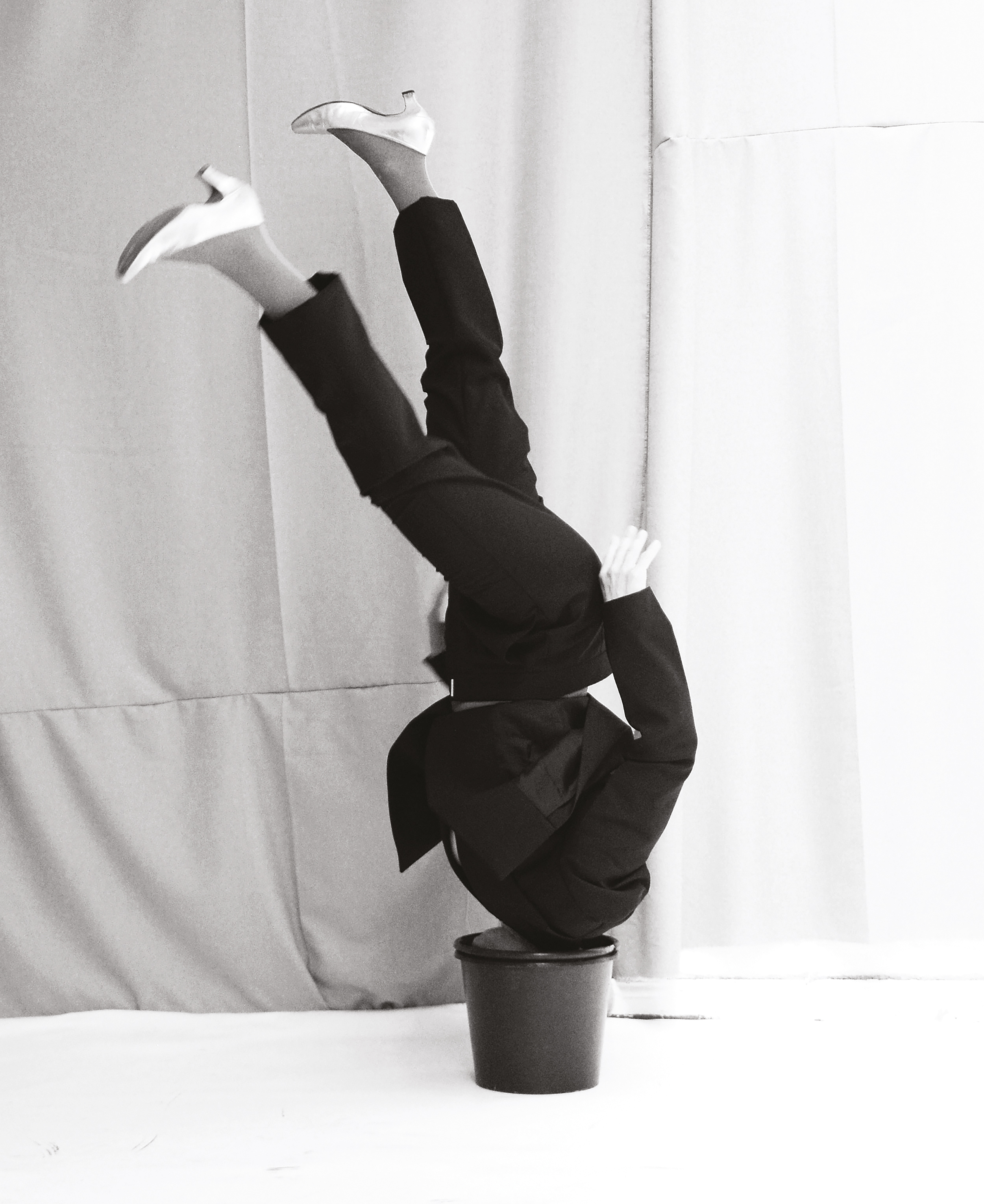

The foundations of Wenzel’s body-first artistic practice, which has moved in new directions in recent years, are coloured by two past lives – as a trained acrobat and as a professional skateboarder, both before the age of 20. “As a kid I was always super physical, and everything circled around movement,” she recalls. “My parents, of course, recognised that early on; I think I was about three when I told them I wanted to be an acrobat. I did a lot of handstands and flick flacks and so on… I often had my legs next to my head. I was very snake-human-like.”

Wenzel’s unusual strength and flexibility were noticed soon enough. A colleague of her mother recommended circus school as an outlet for her boundless energy. There she honed her skills on high-wires and precarious balance boards, as well as in contortion, under the tutelage of a professional Russian acrobat. This period also brought about an introduction to performing, for a live audience before any camera’s lens. While the influence of this time is evidenced in her work today, a shift occurred when Wenzel’s family relocated to Munich. Aged 13 and working under a new coach, she questioned the reality of a professional acrobatic future: “I thought: this looks tough, is this really something I’m aiming for?”

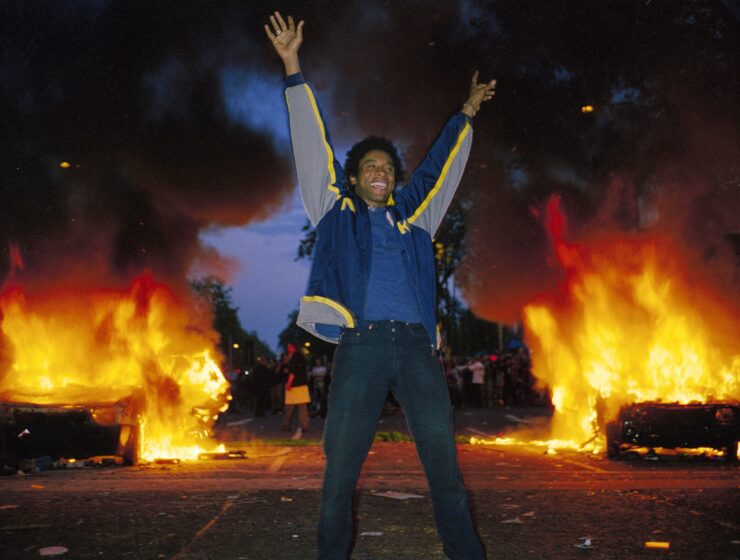

Nerve and tenacity would come in handy for the career in skateboarding that followed. Wenzel quickly rose to the highest levels of the sport, kickflipping and tricking her way forward until battle scars began to take their toll. At 20, a competition-induced knee injury resulted in a series of operations, which in turn brought on a newfound vulnerability. “I lost that childish view on the world that nothing could ever happen to me. It was gone… and I decided I wasn’t going back because you need to have a very particular kind of fearless mindset. I didn’t want to run after something I’d already gained.”

Amid the uncertainty of surgery and recovery, Wenzel cobbled together an application for a design programme at the Bielefeld University of Applied Sciences. Studying her portfolio, admissions officers instead steered her towards photography, noticing the quality of the images she had submitted. “I thought, why not? Sounds easy,” she laughs. “I figured I could do anything while everything else was on hold.” Wenzel’s interest in the body inspired early photographic experiments with portraiture and nudes – but she soon became unsettled by the power dynamics between maker and subject, opting to turn the lens on herself for the first time. She rarely looked back, and a move to Amsterdam’s Gerrit Rietveld Academie lent further clarity to her creative choices.