This article is printed in the latest issue of British Journal of Photography magazine, Activism & Protest, delivered direct to you with an 1854 Subscription.

In her new monograph, she coaxes new narratives by juxtaposing family pictures, collage, photojournalism and portraits of celebrities, and shapes a constellation of images that celebrate the community’s beauty and multiplicity

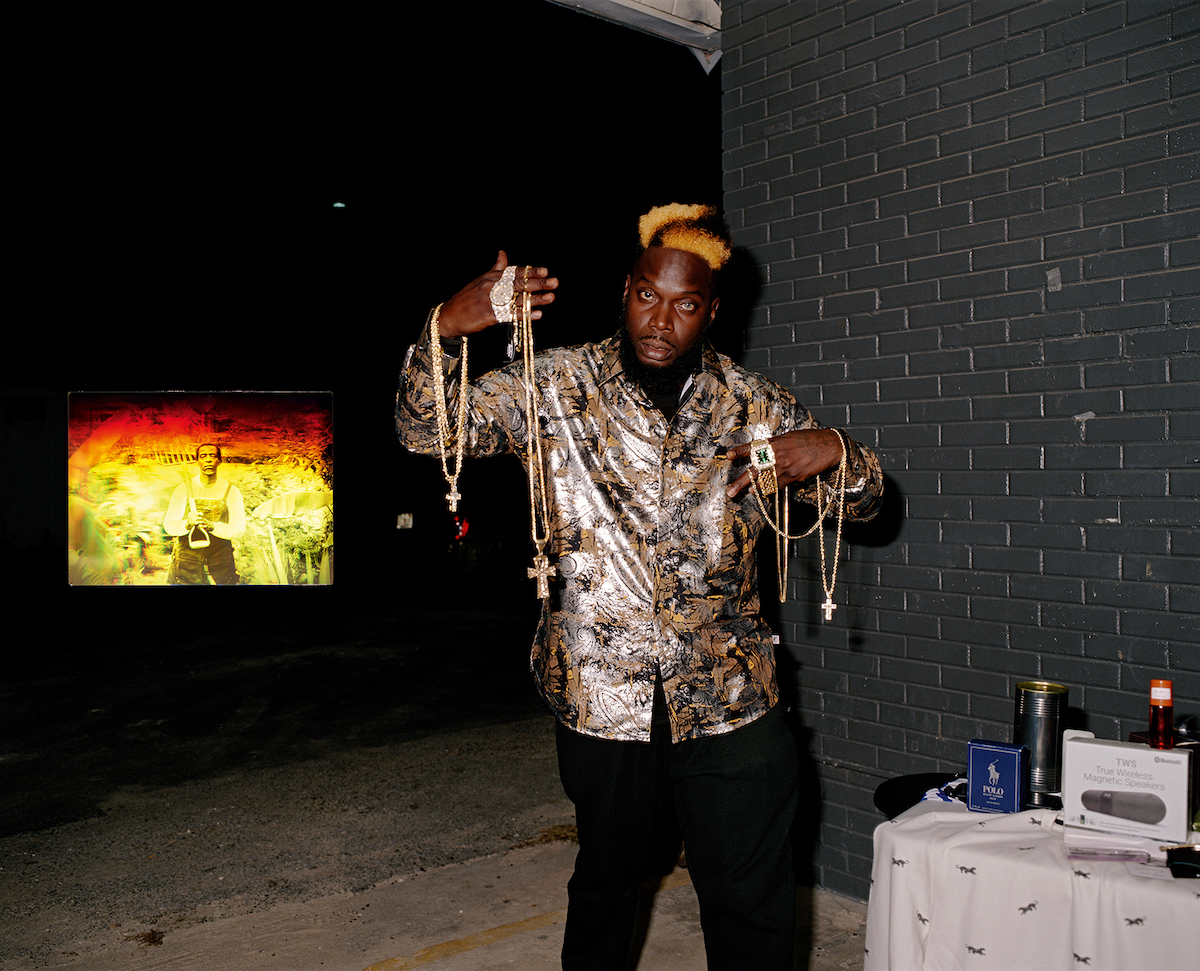

Viewing a photograph made by Deana Lawson absorbs you. Her images function not as reflections of reality but as entry points to different portals of consciousness. She rewards those who look intently. Lawson’s collective body of work ignites a poetic celebration of Black life while exploring notions of mythology, religion, sexuality and dreams. She sheds the reductive ways that popular culture depicts Black people, specifically women, and instead marvels at their beauty and multiplicity. Cross the threshold of the frame and you enter another realm – an invitation to access unseen truths – shifting between past and present, individual and community, and the everyday and sacred.

The New York artist has been aware of the transformational power of image-making since she was nine years old, when she and her sister Dana assisted a photoshoot of their mother. Together they fetched outfits, moved furniture and rearranged props so their mother could make images for a pin-up calendar – a gift for their father. In a lecture for the Art Institute of Chicago, Lawson describes “stomping off to her room mid-shoot”, unsure at the time if she was jealous because she wanted to model or be the photographer.

Still, she knew intrinsically that she coveted a deeper engagement with the process. In many ways, these images were a prophecy. They encapsulate many of the themes at the heart of her work today – family relationships, corporality, love, and the expansive narratives of fantasy and desire created through picture-making.

Lawson never intended to be an artist. She studied international business until an encounter with Diane Arbus’ work captivated her by demonstrating photography’s potential to access a psychological space. Before she started making her own images, Lawson spent hours poring over her father’s family albums, charmed by their intimacy, ceremony and ritual. She began collecting vernacular photography of African American life, scouring flea markets and garage sales for unwanted images that contained a magnetic portrayal of the everyday.

Lawson describes the pictures as capturing “Black innocence” – everyday photos of Black people enjoying life, riding bikes, embracing their babies and hanging out. “Images free from the baggage of history and the violence done to our bodies and community,” she once described. Together the photographs inform the spirit of her work and summon more expansive notions of family that trace lineages across time and geography.

“I feel like every subject that I meet is wearing a crown. I want to capture within them something that represents the majesty of Black life, a nuanced Black life, one that is by far more complex, deep, beautiful, celebratory, tragic, weird, strange.”

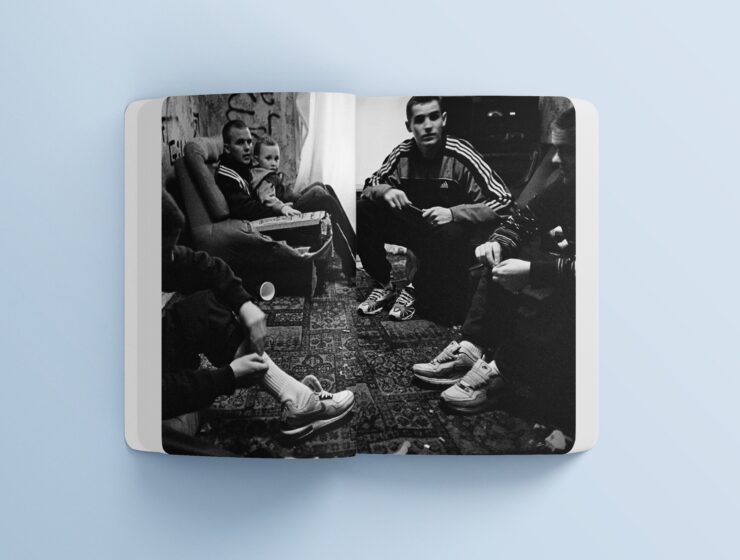

The obsession with vernacular photography and curiosity about the lives of strangers is a central theme in Lawson’s new self-titled monograph, published by Mack this November. The book spans the last 15 years, charting her inimitable practice while sharing images from Lawson’s family archive, and the found material that significantly influenced her work. It will be accompanied by three exhibitions, starting with a show at the ICA in Boston, running from November.

The book is punctuated by collage; varied assemblages that began as reference boards in the photographer’s studio. Over time, they became critical works themselves. Non-sequential and non-chronological, they are an ever-evolving and unresolved entity. The images trade in the world of love, joy and creativity, entangling us in Lawson’s pursuit for an ulterior consciousness. Through the careful sequencing of her photographs, the book subverts monolithic narratives about Black culture, bringing forth a new canon in which Black life is shaped by the community, for the community.

While vernacular photography is a profound influence for Lawson, each image she makes is with intention. Every frame is an act of theatre, rooted in the everyday while reaching for something more. Lawson doesn’t have a set methodology; sometimes she comes with a preconceived idea that is sketched out and used as a blueprint to cast the right character. Other times, the image is born out of a captivation with her subject. Lawson describes her casting process as “time stopping”, often drawn to strangers on the street who remind her of someone she has known in her life. She scouts people on the train, at yard sales and while walking around her neighbourhood in Bed-Stuy. “I feel like every subject that I meet is wearing a crown,” she says. “I want to capture within them something that represents the majesty of Black life, a nuanced Black life, one that is by far more complex, deep, beautiful, celebratory, tragic, weird, strange.”

When Lawson takes a portrait, she understands the exchange as a gateway to something beyond the photograph. The work is not about the lives of Nikki, Shawntel or Roxy – just some of the women she has photographed – but rather about imbuing their bodies and personas with symbolic energy that speaks to a broader set of ideas. This conceptual approach is further extenuated by her staging. Lawson is a master of pose, mood, light and setting. She harnesses the energy of domestic spaces, often those belonging to her collaborators, rich with layers of history and identity. She carefully inserts herself into them, in subtle yet revelatory ways. Activated by lighting, the domestic collides with the studio and the location transitions into something new.

The power of sexuality is magnetic in Lawson’s work. Her protagonists are imbued with a strength that is often manifested as sexual liberation. A riposte to the limiting ways that romance and the Black female body are pictured in pop culture. She insists on breaking that innocence, celebrating beauty and joy at all stages of life. One of her most iconic photographs, Baby Sleep, pictures a young family, the mother nude entangled with her partner, surrounded by a trail of baby toys while the baby sleeps peacefully in a rocker. The direct gaze of the mother, eyes glinting back at us, is a form of radical resistance. The image represents both power and vulnerability, confronting patriarchal ideas about motherhood and sexuality.

Interrogating the tension between the erotic and maternal body is a recurring theme for Lawson, conveyed from art history and popular media, denying mothers the right to be sexual beings. Her interest in the tension between sexuality and the sacred is informed by Audre Lorde’s essay Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power that speaks to the erotic, not as sexual arousal but as a force that can shift our lives in fundamental ways. “When I speak of the erotic,” writes Lorde, “I speak of it as an assertion of the lifeforce of women; of that creative energy empowered, the knowledge and use of which we are now reclaiming in our language, our history, our dancing, our loving, our work, our lives.”

For Lawson, image-making is about being in communion. Not just with her collaborators but with Black diasporic identities and their collective histories. Lawson’s artistic intentions are not political, yet her work undeniably is. She grapples with equity, representation and the indelible trauma of racism embedded in the collective psyche. Intent on imagining new worlds, she creates rich and compelling modes of seeing, all the while affirming that the everyday is personal and political.