Working in industrial spaces for 10 years, and fascinated by the contemporary experience of images, Felicity Hammond makes installations combining imagery and sculpture

Working in industrial spaces for 10 years, and fascinated by the contemporary experience of images, Felicity Hammond makes installations combining imagery and sculpture

The new show at Nxt Museum in Amsterdam tackles the current age of machine learning and the role of artificial intelligence in image-making

The artist’s latest show An Ominous Presence explores the tension between desire, identity, and the act of image-making

The photographer grew up gaming in Abu Dhabi and has drawn on her experiences of virtual worlds and multiple cultures to create her surreal images

Europe’s most popular professional photo sharing software eases the collaboration between artist and brand

Another Online Pervert juxtaposes images from the photographer’s archive with text conversations generated by an AI chatbot, challenging our instincts and perceptions with its eerie reflection of human nature

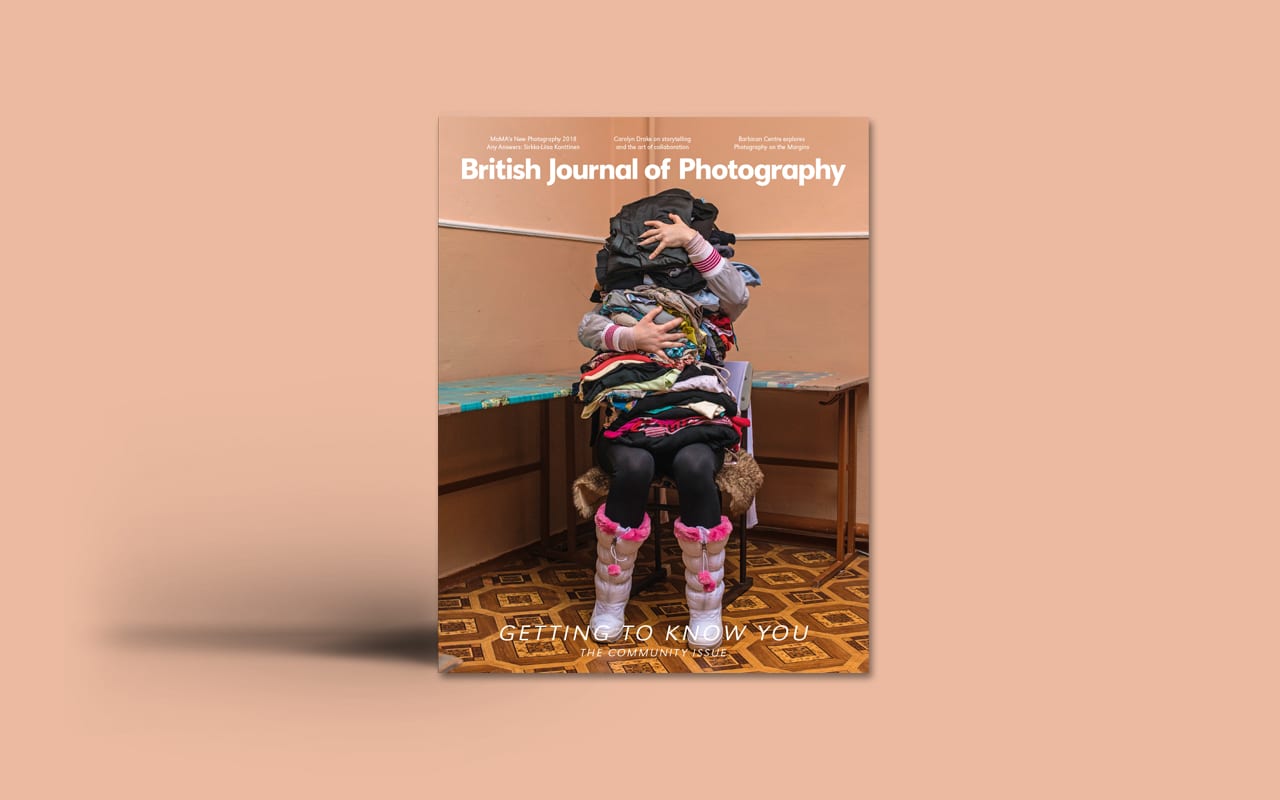

Through a sensitive understanding of what it might offer artists, a new exhibition at Amsterdam’s Huis Marseille makes a case for Instagram’s significance

“What do I know about it? All I know is what’s on the internet.” So said Donald Trump in an interview in March 2016, after he was confronted about the legitimacy of a video he had tweeted, along with the claim that the protester it depicted was a member of ISIS. The video has since been proved as a hoax, neatly demonstrating the difficultly of navigating between truth and fiction in today’s digital landscape. In a world where even a layperson can manipulate images on their phone, and spread them to thousands of fake followers with one click, how can we begin to know what is #real?

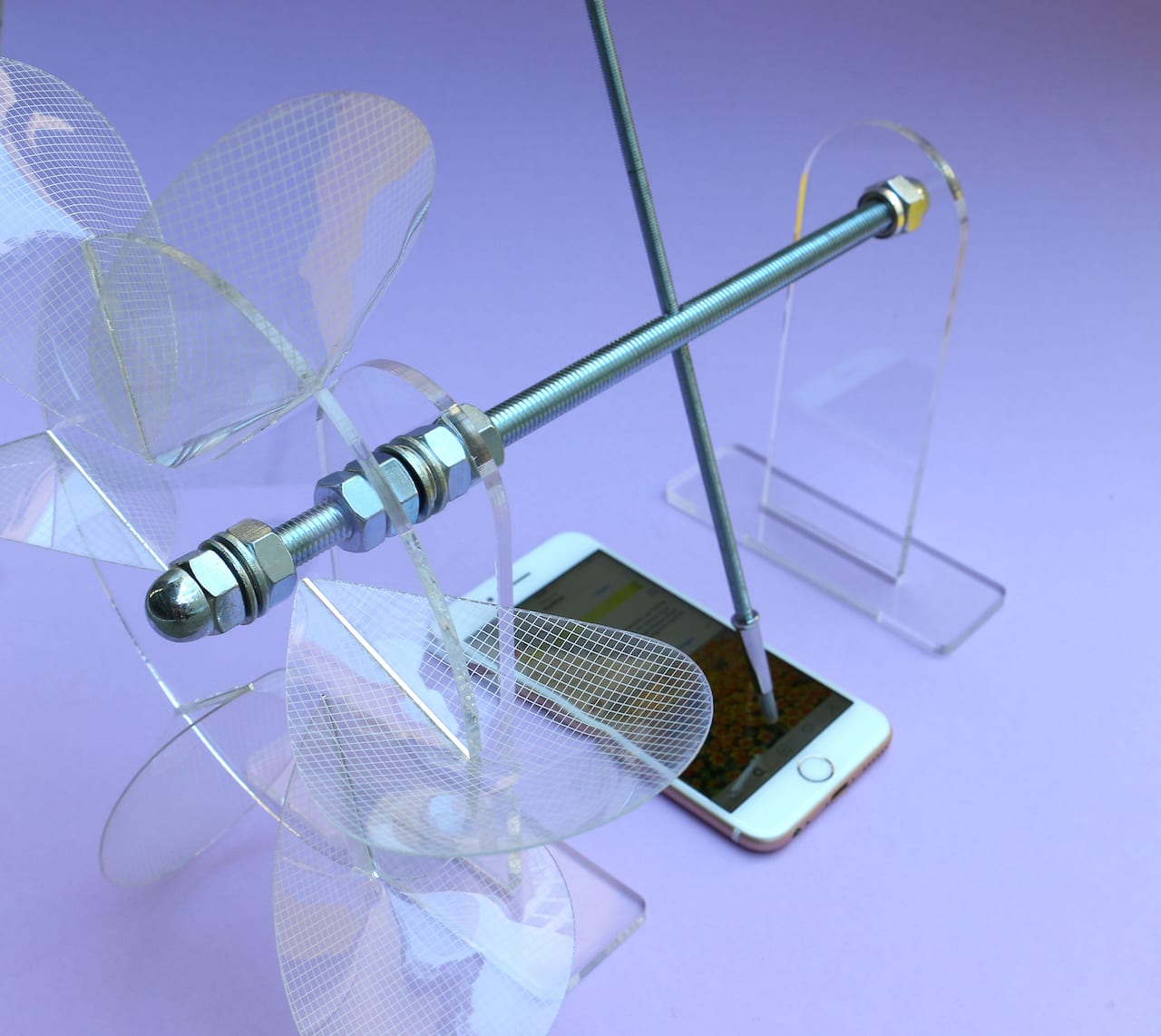

It’s the kind of question that All I know is what’s on the Internet will pose, a new exhibition opening at The Photographers’ Gallery, London including work by 11 artists and collectives. It includes “social media machines” made by Australian designers Stephanie Kneissl & Maximilian Lackner, built to maximise activity and likes; and wall-mounted installations by Eva and Franco Mattes that reveal the lesser-known, surprisingly personal, world of online content moderators. Curated to draw attention to the neglected corners of digital image production, the show helps visualise the vast infrastructure of online platforms, and the enormous amount of human labour needed to keep it churning.

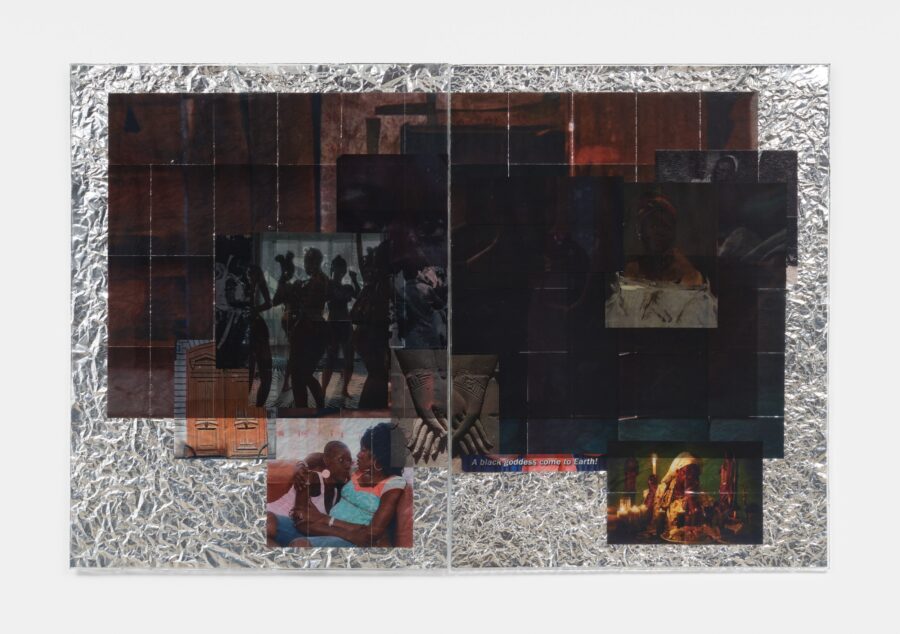

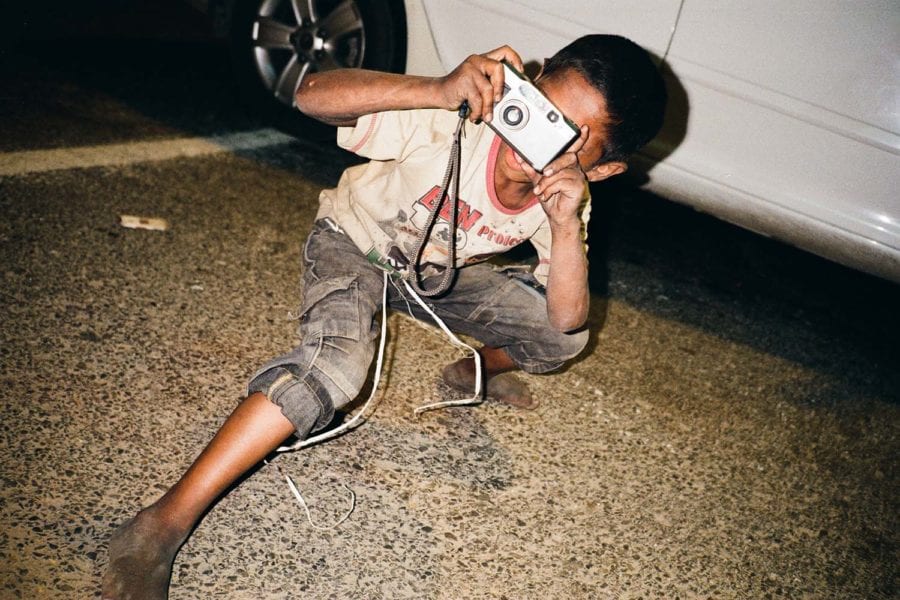

Last month BJP focused in on group work; this month we’re looking at a different kind of collaboration – projects in which photographers engage in a two-way dialogue with their subjects. One of the best – and the best-known – examples is Jim Goldberg, who works with subjects such as teenage runaways and migrants to tell wide-sweeping stories of marginalisation and economic disparity. Using an eclectic mix of photographs, archive materials and video, and both marking up himself and invites his subjects to write on, he creates complex montages guided by his sense of “intimacy, trust and intuition”. Incorporating the perspectives of the communities and subcultures he represents, his work is informed by his own background in a blue-collar family in New Haven.