Self Portrait with Pocket Square © Sarah Maple

This article is printed in the latest issue of British Journal of Photography: Performance. Sign up for an 1854 subscription to receive it at your door.

Hoping to reignite appreciation for a ‘neglected’ UK photo scene, James Hyman will open the Centre for British Photography at the end of this month. How will the new institution serve the community?

On 26 January, the Centre for British Photography will open on Jermyn Street, just off Piccadilly Circus in central London. Boasting three floors of exhibition space, a library, a print sales room and a shop, the centre will be free to the public and host talks and events as well as shows. Spread over 745 square metres, it is a significant entry in the UK photography scene. But the new centre comes with a twist. Though public facing, it is a private initiative; the brainchild of James Hyman and funded so far via the Hyman Foundation, the charity he set up with his wife, Claire, in 2020.

Hyman believes photography from the UK is underappreciated, especially within the UK, and says he has built the Centre to change that. He will support and fund it for two years in the hope that others join him, and that it eventually becomes self-sustaining. The aim is that ultimately it will be independent enough for him to step away.

“We’ve got two phases and two kinds of strategies,” Hyman explains. “What we’re trying to say is, ‘People in photography in this country have been saying for years that we’re neglecting what’s happening here. We’re celebrating or platforming things abroad and that’s terrific, but sometimes it feels like it’s at the expense of what we have here’.

“Phase one is like a proof of concept – [making sure] that [the Centre] is what people want and will support, and can help shape,” he continues. “The second aspect is the funding. We set up a Foundation – this is all being supported by the Foundation – and until we get other people on board… the onus is on me. I can’t fund it forever… Whether that’s Arts Council England or other foundations or individuals… we need a kind of coalition of partners who will share this belief and vision for it to all come together.”

Hyman, who holds a PhD from the Courtauld Institute of Art, is a gallerist and collector. Before the Foundation, he started the Hyman Collection with Claire in 1996, which today includes over 3000 artworks from all over the world. For the last 15 years, however, it has focused on British photography, as the Hymans endeavour to acquire whole series, multiple series, and even entire exhibitions of work.

The Hyman Collection includes historical names such as Bill Brandt and Bert Hardy and well-established documentary photographers such as Tony Ray-Jones, Anna Fox, and Martin Parr. It also features newer and more experimental image-makers including Juno Calypso, Bindi Vora, and Paloma Tendero, as well as artists working with images, such as Jane and Louise Wilson, and Gillian Wearing.

In 2015, the Hymans set up a website – britishphotography.org – which catalogued the Collection and gave it a public face; this resource made it more accessible for institutions, says Hyman, many of whom have borrowed works over the years. More recently, the Collection has staged three exhibitions in public galleries. These include Modern Nature: British Photographs from the Hyman Collection at the Hepworth Wakefield in 2018– 2019; Jo Spence: From Fairy Tales to Phototherapy. Photographs from the Hyman Collection at the Arnolfini, Bristol, in 2020–2021; and A Picture of Health: Women Photographers from the Hyman Collection from May 2020 to July 2021, also at the Arnolfini.

Later, the Hyman Foundation was set up to “promote and support photography in Britain in all its diversity”, and award grants and commissions with a particular emphasis on women and young artists. It also funds research and scholarships, and provides mentorship for artists of all ages on how best to handle their careers and archives. Its advisers include Renée Mussai, the former senior curator at Autograph and recently appointed artistic director and chief curator at The Walther Collection in New York, and Michael G Wilson, a film producer, photography collector and founder of the Wilson Centre for Photography.

Exhibitions in focus

Tracy Marshall-Grant, the arts director, curator and producer, is another adviser, and also joined the Centre for British Photography as deputy director following her departure from the Royal Photographic Society at the end of 2022.

“I’m in the mix to try and start putting together the traditional public gallery funding mechanisms and to guide,” she says. “The outcomes and the platforms that we produce from the Centre are what my experience for the last decade – working in the public gallery world – shows that you need. Also, just that general sense of coordinating the gallery space from a public mindset.”

Marshall-Grant advised on the Centre’s inaugural exhibitions, which aim to showcase contemporary photographers and some of the work in the Foundation and Collection.

The opening exhibitions include four In Focus displays, for example, all of which have had Hyman backing. Wish You Were Here by Heather Agyepong was recently commissioned by the Hyman Collection; Spitting by Andrew Bruce and Anna Fox is a response to the Spitting Image puppets the Collection commissioned in 2015; Natasha Caruana’s Fairytale for Sale was recently acquired by the Collection; and Jo Spence: Fairy Tales and Photography is an archive project the Centre collaborated on with the Jo Spence Memorial Library Archive at Birkbeck, University of London.

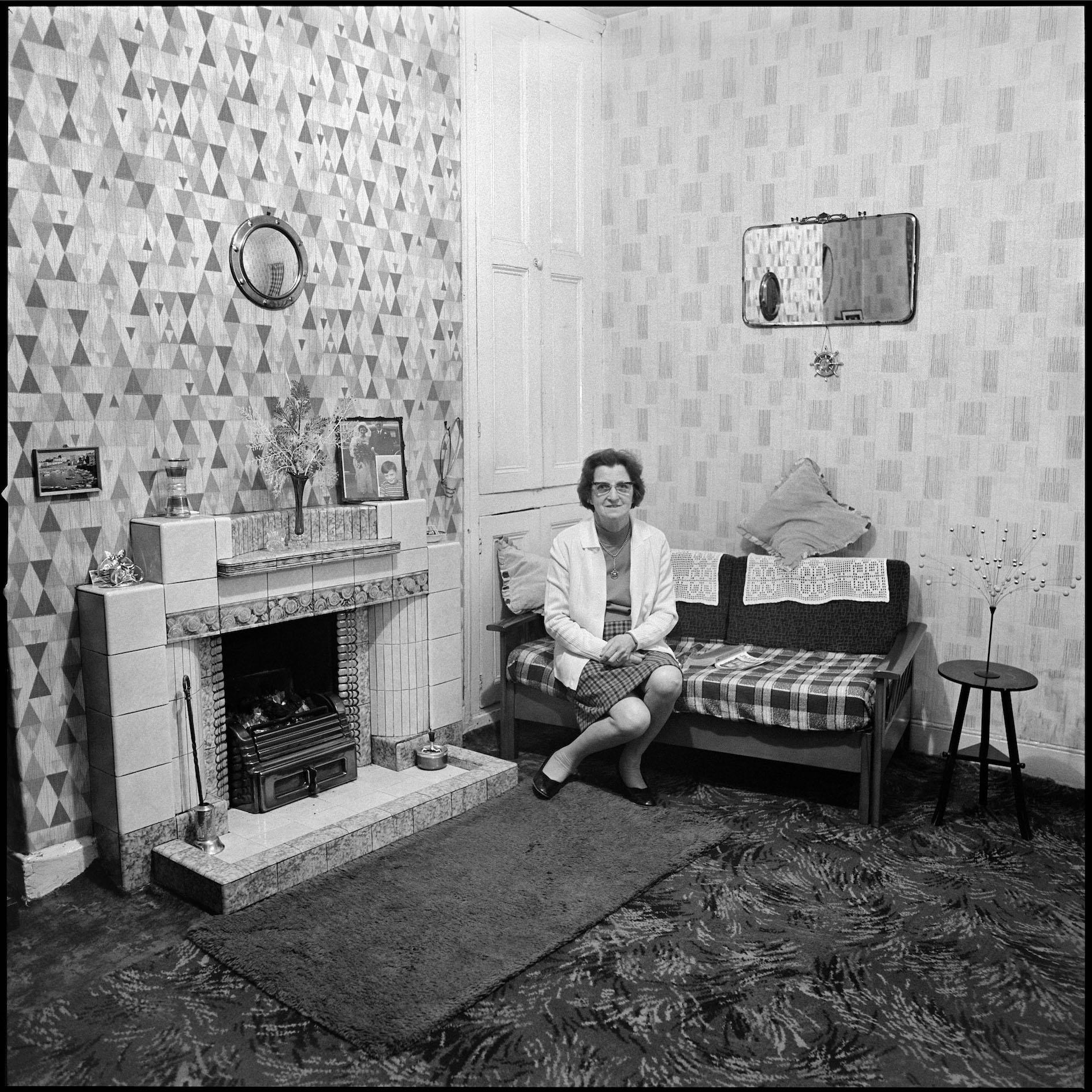

In the basement you will find The English at Home, an exhibition of over 150 prints drawn from the Collection, which includes a range of images from Bill Brandt to Richard Billingham.

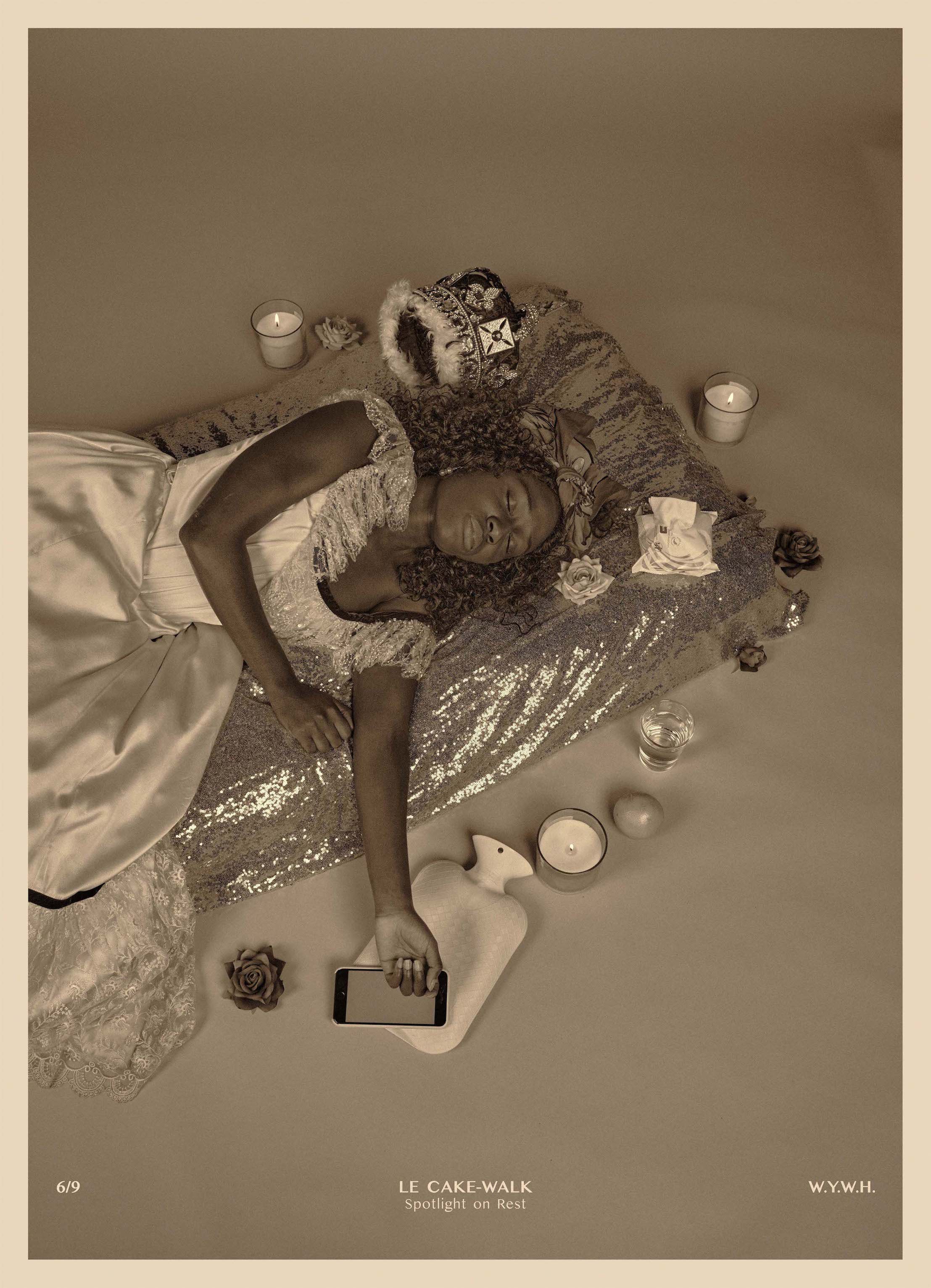

On the ground floor is an exhibition of work by 12 women photographers, titled Headstrong: Women and Empowerment. Hyman is keen to point out that only two of those 12 currently have work in the Hyman Collection; he also highlights the fact that this exhibition is co-curated with the campaign group Fast Forward: Women in Photography – an organisation working to improve the representation and visibility of women in photography – and is in the Centre’s main space.

“That’s making a big statement, that the first show is done by Fast Forward,” he says. “I think that will surprise people when they come in. It’s not just about our Collection, we have taken ourselves out of it and given them that platform.”

Hyman says that this approach will continue, and he is keen for the Centre to set up partnerships such as working with external curators or setting up education programmes in collaboration with academic institutions. He also plans to give the platform to young, upcoming curators. “These are people in their twenties, and this would be an opportunity to get younger voices, to be more diverse and inclusive,” he says. “It’s not just us dictating a programme.

“We empower somebody else to curate and we provide them with the backup. We’re getting a different voice” – James Hyman

“We have the privilege of starting something new,” he continues. “If you’ve inherited an organisation [with its own] structures, bureaucracies and ways of doing things, you’re tied to the curatorial team. You’ve got the idea that you’re doing everything in-house. Starting from scratch… we don’t need a whole curatorial team here. We empower somebody else to curate and we provide them with the backup. We’re getting a different voice. And if they’re curating, they’ve got the Collection which they can use if they want to. But if they don’t want to, and they want to bring attention to people who are not in the Collection, that’s even better.”

Hyman hesitated to employ an in-house curator at the Centre for British Photography, not only because he is keen to work with external curators but, he says, if the need arises he can oversee shows himself. While Hyman certainly has experience in photography and in curating photography exhibitions, this makes him self-appointed curator and director of the Centre for British Photography, and that is a powerful position.

However, in this he is not alone. The Martin Parr Foundation – set up in 2014, and opening its space in Bristol in 2017 – also opens up a private collection, provides space for exhibitions by other photographers, and offers commissions. It also does not have a full-time curator.

“We run our programme by the trustees, we just sit down together as a group and talk about what’s coming up,” Martin Parr tells me. Unlike publicly funded institutions, he adds, “we don’t have to spend a lot of time filling out Arts Council England forms”.

“There isn’t a huge market for British photography. If, through doing something like this, that market was to grow, that’s fantastic for everybody. Hopefully, that benefits all the photographers” – James Hyman

The art of giving back

Further to this, the Peter Marlow Foundation is set to open in 2024. A space of just over 250 square metres in Dungeness, Kent, it will house the photographer’s archive, plus work from other image-makers and a library of books by Magnum Photos members. It will also offer exhibitions, residencies, workshops and talks to schools, the public and professionals. The Foundation was set up in 2020 after the Magnum photographer’s death four years earlier and has charitable status; its trustees include Marlow’s partner, Fiona Naylor.

Parr concedes such institutions are new to the UK, but believes they are the logical solution to deal with a large archive. Part of his motivation for founding the MPF was “to house my own substantial archive”, he says, which includes his work and his collection of prints and artefacts by other artists.

He did not want his daughter “to be lumbered with working out what to do with it” after his death. Parr has given away collections in the past – he part-gifted, part-sold his collection of over 12,000 photobooks to Tate in 2017, for example. But that was not an option for this archive, he says, because publicly funded institutions would not accept it in its entirety.

For its part, the Hyman Collection has made donations in the past, giving 125 photographs to the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, USA, in 2018, and 100 photographs to the Bodleian Library in Oxford in 2019. Hyman says he has since become “a bit concerned” about donating to institutions, arguing – without naming anyone specific – that they can overlook donated work.

He worries that photography can be neglected in organisations that collect other media, for example, and that British photography can be bypassed by those working with international artists. He also thinks institutions can undervalue work they did not have to buy. “Things get lost,” he says. “They’re not a priority.”

However, Hyman is keen for the Centre for British Photography to work with other institutions, not try to replace them, and there is plenty of room for all. He wants to give photography made in the UK a boost, he says. And while conceding this may translate to a market uplift, he insists that it will not benefit him personally. “At the moment, I’m losing a phenomenal amount of money,” he laughs. “I don’t need to be doing this.

I didn’t need to get up at 4.30 in the morning and work seven days a week, stretching myself physically, emotionally and financially. I don’t need it, I really don’t. I’m doing it because I believe in it, and because I think there is an audience for it, and because I want to put something back.

“There isn’t, as we all know, a huge market for British photography,” he continues. “If, through doing something like this, that market was to grow, that’s fantastic for everybody. Hopefully, that benefits all the photographers. It benefits the institutions, there will be more exhibitions, more books on photography, photographers might actually be able to earn a livelihood through their practice, rather than teaching or [doing] advertising or anything else. Everyone else benefits, because we’re not actually looking to sell the Collection. In some ways that makes it more difficult for us – if we keep collecting, everything’s just going up in price.”

The Centre for British Photography opens to the public on 26 January