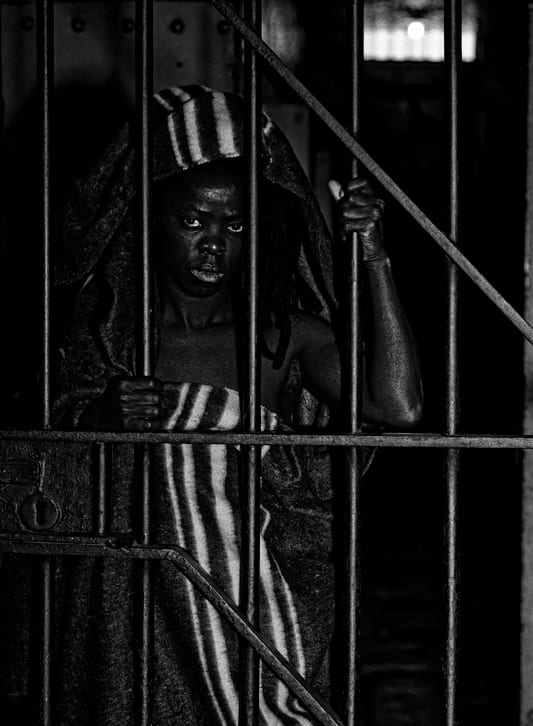

Bayephi III Constitution Hill, Johannesburg, 2017. © Zanele Muholi, courtesy of the artist and Autograph, London.

Senior Curator and Head of Curatorial & Collections at Autograph, London, looks back on the year just past: its effect on her outlook, what got her through, and what she will leave behind

Renée Mussai is responsible for some of the most compelling exhibitions in recent years. In the two decades that she has worked at Autograph, London, as Senior Curator and Head of Curatorial and Collections, Mussai has organised global exhibitions, while also commissioning a diverse roster of contemporary artists, and developing artistic programmes for the charity. Recent exhibitions include immersive gallery installations with Zanele Muholi, Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness (2017–present); Lina Iris Viktor, Some Are Born To Endless Night – Dark Matter (2019–20), and the critically acclaimed archive research programme The Missing Chapter – Black Chronicles (2014–2018). Mussai has also published and lectured internationally, on visual culture and curatorial activism. Her writing features in numerous artist monographs, scholarly journals and anthologies.

She is a regular guest curator and a former non-resident fellow at the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard University, Cambridge, US, and a Research Associate at the Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre, University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Along with being an Associate Lecturer at University of the Arts London, she is currently a PhD candidate in History of Art at University College London, where she is completing a doctoral thesis on 19th century “raced” portrait photography and contemporary curatorial care.

Below, Mussai shares her reflections on and experiences of 2020.

I spent a majority of my working days, and nights, at home in London: in our living room/office/study/library, or outside on the balcony, with my laptop, books, and a sea of endless, and very colourful, post-it notes. Our balcony has been such a blessing, especially during the first lockdown: a small floating haven, filled with light, air, and sun.

Occasionally I would venture to the gallery, Autograph, in Shoreditch, east London. We have been closed since March, and will not re-open again until next spring. It’s been lovely to see colleagues in person a couple of times, albeit briefly, and artworks in situ. It was the strangest sensation to be in a building, which is ordinarily so full of energy and people, now deserted.

2020 has gifted me a new passion for walking. I’ve been walking everywhere, for hours at times, and enjoying the time for reflection and discovery that these solitary excursions offer. There is so much to explore, especially in our local neighbourhoods Stoke Newington, Hackney and around Highbury & Islington. Abney Park, for example, is an incredible gargantuan maze of a cemetery and woodland park with graves dating from the late 1700s. I had no idea, and only recently learnt that Joanna Vassa, the daughter of the abolitionist and anti-slavery advocate Olaudah Equiano, was buried there in 1857.

We spent one day at the beach, visiting the wonderful artist Aida Silvestri and her family in Folkestone. That was very special and a real treat. I swam for ages, early morning, with hardly anyone in the water. It was already autumn, so a little fresh, but utterly rejuvenating. I miss being near the sea…

Miles Davis’ A Kind of Blue and Lift to the Scaffold were the perfect soundtrack/soundscape to the early months of 2020. I played both albums over and over. So timeless, so beguiling, enveloping, and quietly reassuring in their melancholy warmth, like a continuous sonic embrace. The latter was recorded over a couple of nights from dusk till dawn, wholly improvised, in Paris, in 1957; precisely 100 years after Joanna Vassa was buried in Abney Park cemetery. And, coincidently, also, the birth year of someone I love dearly and have missed terribly this year.

I’ve been reading and re-reading everything that the late Octavia E. Butler ever wrote, which has been a lifeline throughout 2020; all her novels, short stories and interviews. I keep finding myself happily immersed in her speculative fictional universe(s) … From her Xenogenesis trilogy, about alien and human races creating new wondrous life forms through sensual haptic rituals, and her final book Fledgling, about a young genetically modified Black vampire awakening in the dark with dementia, to her prophetic Parables. I am deeply grateful for her voice and vision: such an incredible insight into humanity and the poetics of difference. And I can’t help thinking about what she would make of this current time we are living through…?

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay’s Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism and Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women and Queer Radicals have reminded me what critical and imaginative scholarship can, and should, be. Both are virtuoso, nourishing, thought-provoking, and generous offerings. I’m holding on tightly to the notion of continuously undoing, unlearning, unravelling, and imagining otherwise, always.

I have watched hardly any series, or films, at home this year. Given everything else in our lives evolving around screens, I have felt little desire to indulge the digital realms further. I did, however, enjoy Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill Vol. 1 & 2 at our local cinema, the Screen on the Green on Upper Street, Islington, between lockdowns, which is still such a great movie! It felt like a much-needed moment of pure escapism. And Uma Thurman is simply divine in it.

I do miss going to the movies regularly. It is one of my favourite places to unwind and process/feel emotions… The last film I saw at Dalston’s Rio Cinema with a close friend just before the first national lockdown was Toni Morrison: The Pieces I am, which is a beautiful, intimate portrayal of an amazing human being. I left feeling so inspired, and even more in awe of her. And remember us desperately looking for hand sanitiser everywhere in Dalston afterwards, in the pouring rain.

“I’ve enjoyed a renewed appreciation of solitude this year, and a more astute understanding of the fragility of our bodies and minds”

I’ve seen very few exhibitions this year. But I am so glad I got to visit Zanele Muholi at Tate Modern, the gallery’s first major retrospective dedicated to a queer, Black, African non-binary artist. And also Autograph’s Sunil Gupta: From Here to Eternity at The Photographers’ Gallery, which I saw on the opening day in September. I only wish these shows were not happening during a global pandemic. They are two hugely important artists committed to a life of visual activism and cultural politics: bold, brave, necessary, whose work means so much especially to queer communities of colour, and beyond, and should be seen and celebrated, without restrictions. The timing here feels especially cruel.

A photograph I have returned to often this year is Bayephi III [below], from Zanele Muholi’s ingenious series of self-portraits, Somnyama Ngonyama – Hail the Dark Lioness. One hundred images from the series were published in the award-winning and acclaimed monograph by Aperture in 2018. The portrait also features in the recent Tate catalogue accompanying the current exhibition. Both of which I had the pleasure to contribute to.

The image was commissioned for Muholi’s solo exhibition at Autograph in 2017, to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the 1956 March on Pretoria when tens of thousands of women from different cultural backgrounds came together to protest against discriminating pass laws restricting free movement during South Africa’s apartheid era. Taken at a former prison site on Constitution Hill in Johannesburg, it perfectly encapsulates this sense of confinement and isolation … It is a visual meditation on loss: the loss of lives, of our freedoms, of our right to be with loved ones. The demarcation of different chromatic ‘zones of being’ within the image, the cracks on the wall, the lone figure enveloped by a blanket, their head held high … all very symbolic of 2020, in this year of contagion, turmoil, and protest against injustices and inequalities so deeply ingrained in our systems, histories and societies globally: Covid, Brexit, Black Lives Matter … But, I also see a sense of hope, and resilience, imbued in this fabulous portrait: a futurity, if you will. It gives me strength.

My favourite word in 2020, which I will continue to embrace in 2021 is: otherwise. It is so full of promise, imagination, and possibility.

I’ve enjoyed a renewed appreciation of solitude this year, and a more astute understanding of the fragility of our bodies and minds, (plus a passionate love for CBD chocolate).

I will take forward the burning desire for, and a commitment to, ‘shaping change’. The courage to embrace change the courage to practise refusal – to say “no” – and the courage to practise happiness, pleasure, kindness, and gratitude… to relocate and reignite what the Japanese refer to as ikigai: the place inside us where desires, passions, missions, ambitions, visions, etc. align.

I hope to leave behind a continual sense of anxiety and urgency, the tendency to keep saying ‘yes’, and bad habits such as under-sleeping and over-working. To live more fluidly attuned to the principles of wabi-sabi: embracing transience and imperfection.

To let go of the belief that time and our capacity is endless and elastic. I want to nurture a new relationship with time: to spend time more wisely on things that matter, and with people who matter. To keep nurturing friendships carefully. 2020 has taught me to appreciate family and loved ones more than ever. It has made me acutely aware of the privilege of spending time with those we love, and respect, and the pain of perpetual separation.

Most importantly, a sense of care – for one another, for the environment, for the planet, for the self. To move around less, work less, be still more often, rest more, breathe more… To be less digital, more cerebral; fewer screens, more nature.