This complex process is brought to life in her ongoing project, the roots of which coincided with her discovery of photography during her fine art degree at the European School of Visual Arts: “I could meet people and discover things that I wouldn’t have if I didn’t have a camera,” she recalls.

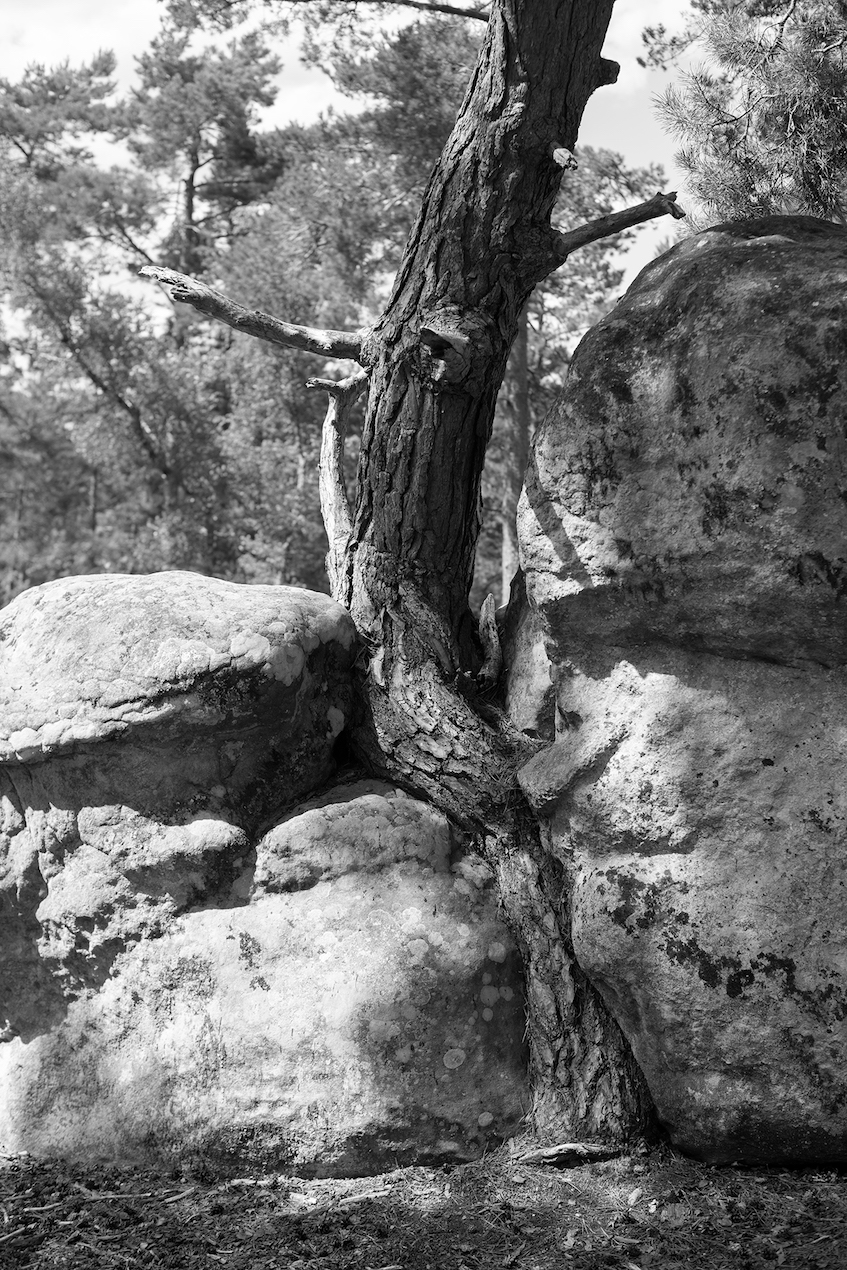

Her relationship to the medium intensified during a six-month research programme in China in 2017. Azzopardi was initially hesitant about travelling so far because of her depersonalisation disorder, but in the suburbs of Shanghai she experienced a strange sense of homecoming. “What struck me in China were the huge changes in the cities and countryside. Everything was construction or destruction. There was no limit between urban and rural,” she says. “I felt that the identity of the landscape reflected the lack of consistency in my body. I recognised myself in it, and I felt comfortable there.”

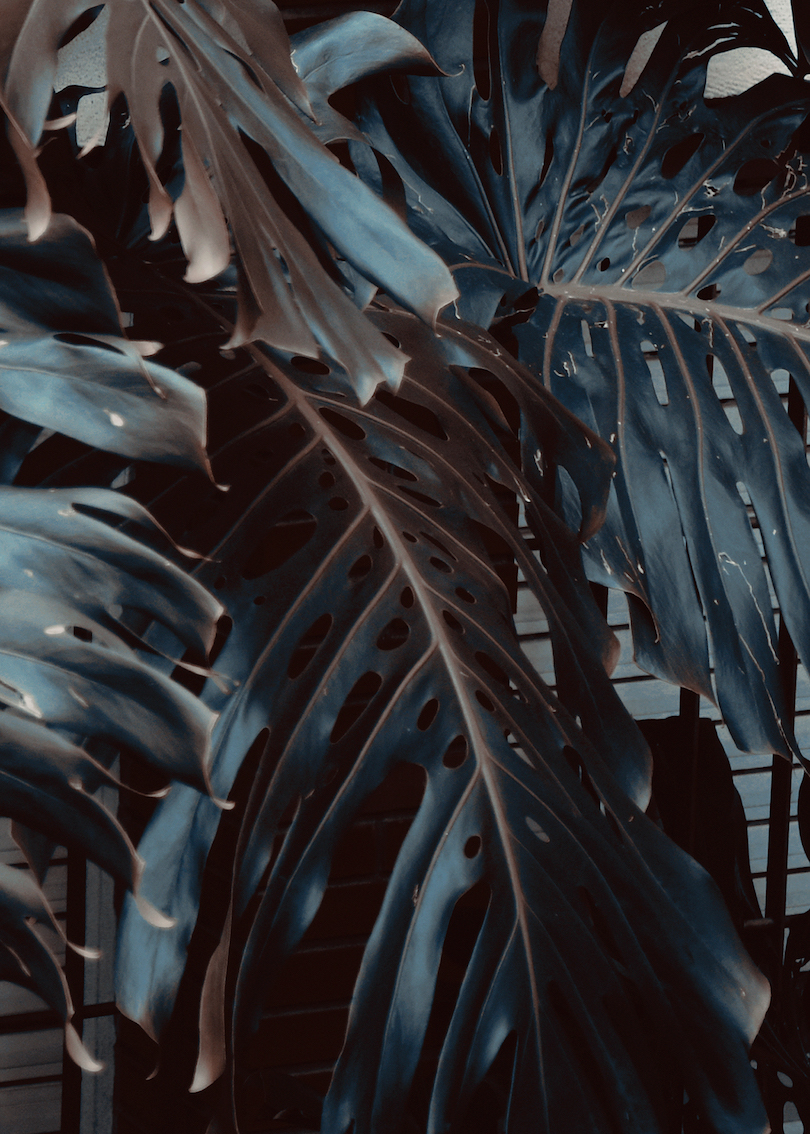

In an attempt to represent this “spectral” experience, Azzopardi began to hunt for ghosts: a dog in an abandoned building, a dust sheet blowing in the wind, a glint of street light on an old mirror. “The important thing was the sensation of coming face-to-face and recognising each other, of echoing the spectrality of the other,” she says of her subjects.