The photographers discuss the close relationship between an energetic and free practice with political agency and belonging

We are only just beginning to grapple with the camera’s fraught history as an oppressive weapon and how a legacy of misrepresentation has impacted human rights, politics, identity formation and the visual construction of race, gender, sexuality and so on. ‘Representation justice’, a term coined by Harvard Professor Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, describes photography’s vital role in expanding the notion of who counts in society. It speaks to the ways in which the camera can be an ally – calling communities into being and embracing the transformative potential of photography to create a new vision of humanity.

The inextricable relationship between art and belonging is being affirmed by a new generation of image-makers who employ joy as a tool of resistance. Their approach is imbued with political agency – some more overtly than others – while focusing on the catalytic energy of joy and freedom. For them, storytelling is used to imagine new worlds. They understand the body as a site upon which to inscribe meaning, activating a new set of values that honours their unique vision with grace, pleasure and an infectious sense of feeling alive. These expansive visual encounters allow new modes of seeing and feeling to emerge.

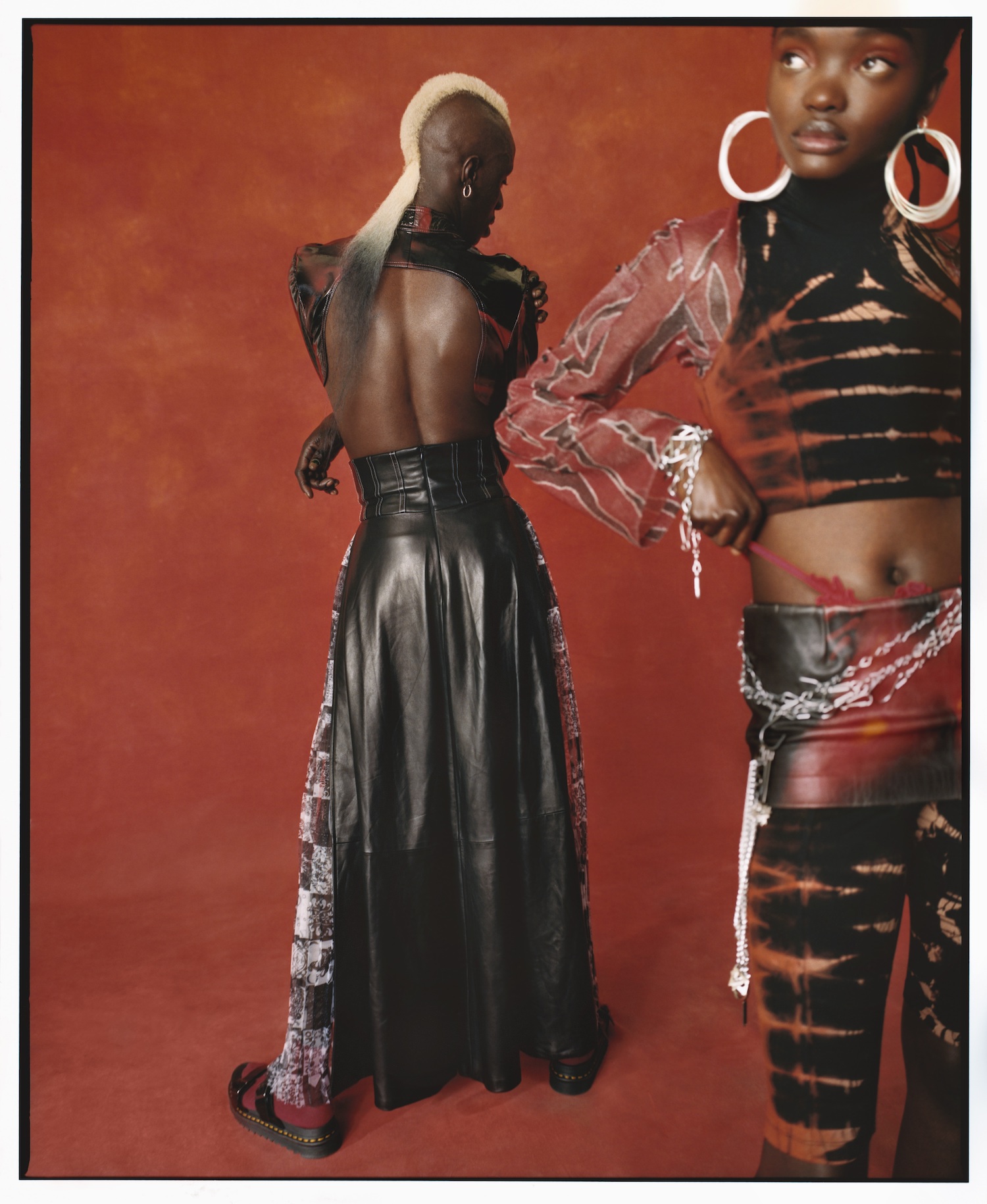

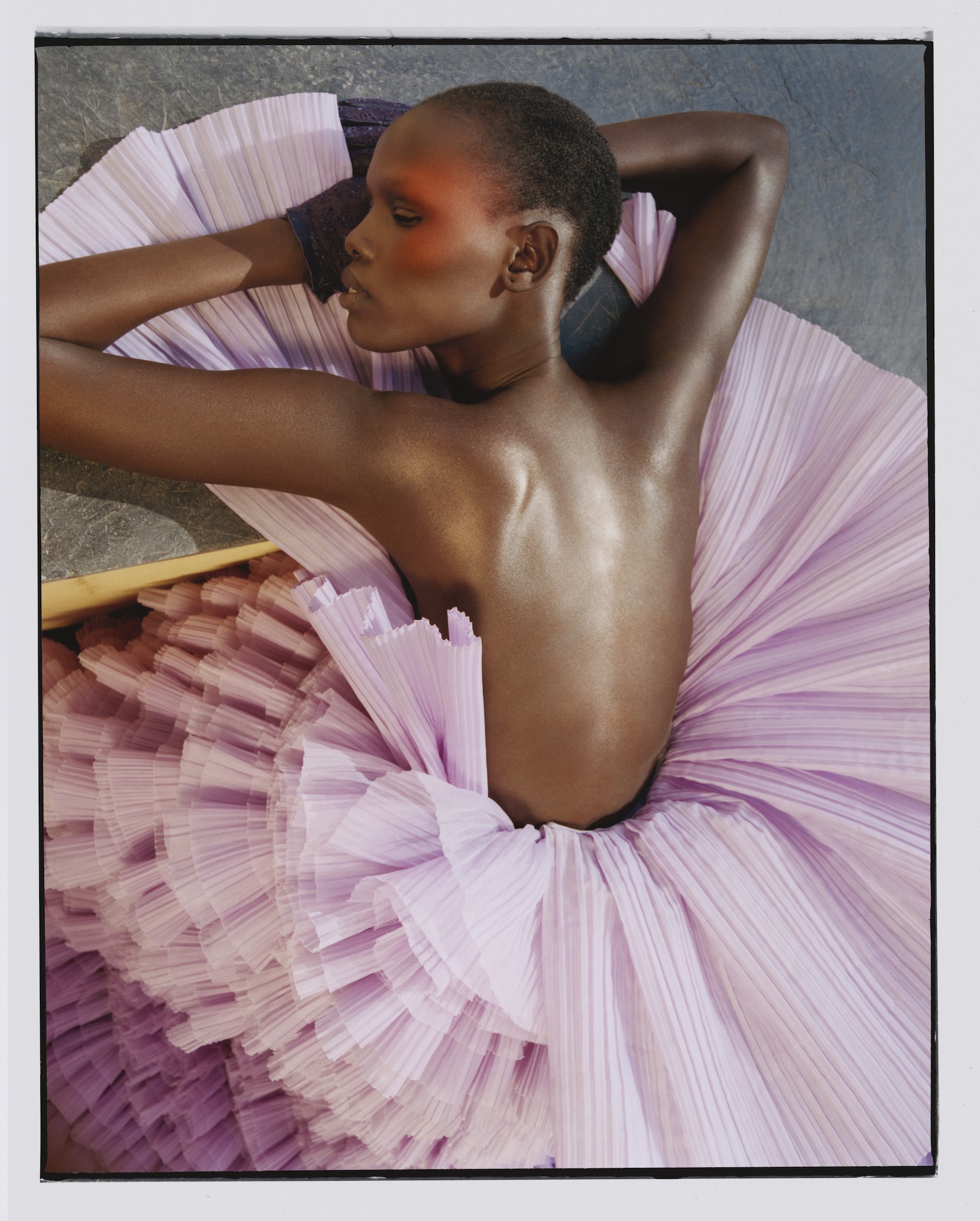

Nadine Ijewere

“Radical hope is our best weapon,” says writer Junot Díaz. In these fraught times, he explains that “radical hope is not so much something you have, but something you practise.” This sentiment reverberates through Nadine Ijewere’s photographs. The London-born photographer has spent the last decade creating images that highlight underrepresented notions of beauty. Her exuberant practice is a mediation on power and belonging, while also holding space for women of colour to articulate what beauty and freedom mean to them.

“No person should ever feel like they are invalid because they are not seen,” says Ijewere. “As a teenager, when I looked through my mother’s fashion magazines, I felt like I needed to be something different because what I was, wasn’t being shown. I never started taking photos with the primary intention to make a political statement. I just loved taking photos.” She adds: “As the work went on, the importance became more apparent. I realised I wanted to give young people the references I didn’t have when I was growing up.”

What is radical about Ijewere’s approach to fashion is how she relentlessly evokes happiness and warmth. Her images are intimate yet universal, and unlike so many fashion photographs, they welcome you into the fantasy with open arms. Her new book is a case in point. Our Own Selves, published by Prestel, traces the evolution of her work, featuring fashion editorials, commercial endeavours and personal work. At its core, it embodies the resplendent majesty of Black beauty. Each frame is dynamic, alive and full of grace. Through careful consideration of light, colour and composition, she builds worlds that reference personal influences from her Nigerian-Jamaican heritage while simultaneously reimagining the concept of beauty as something multifaceted and individual. Her photographs do not just break free from fashion’s tired tropes, they render them obsolete.

Ijewere does not describe her work as political. For her, it’s simply visioning the beauty and style that has always surrounded her. Despite the endless accolades of firsts – most notably, she was the first woman of colour to shoot the cover of any Vogue in the magazine’s 125-year global history – Ijewere is more focused on a world where diversity is not disruptive but rather the norm. To be the last first.

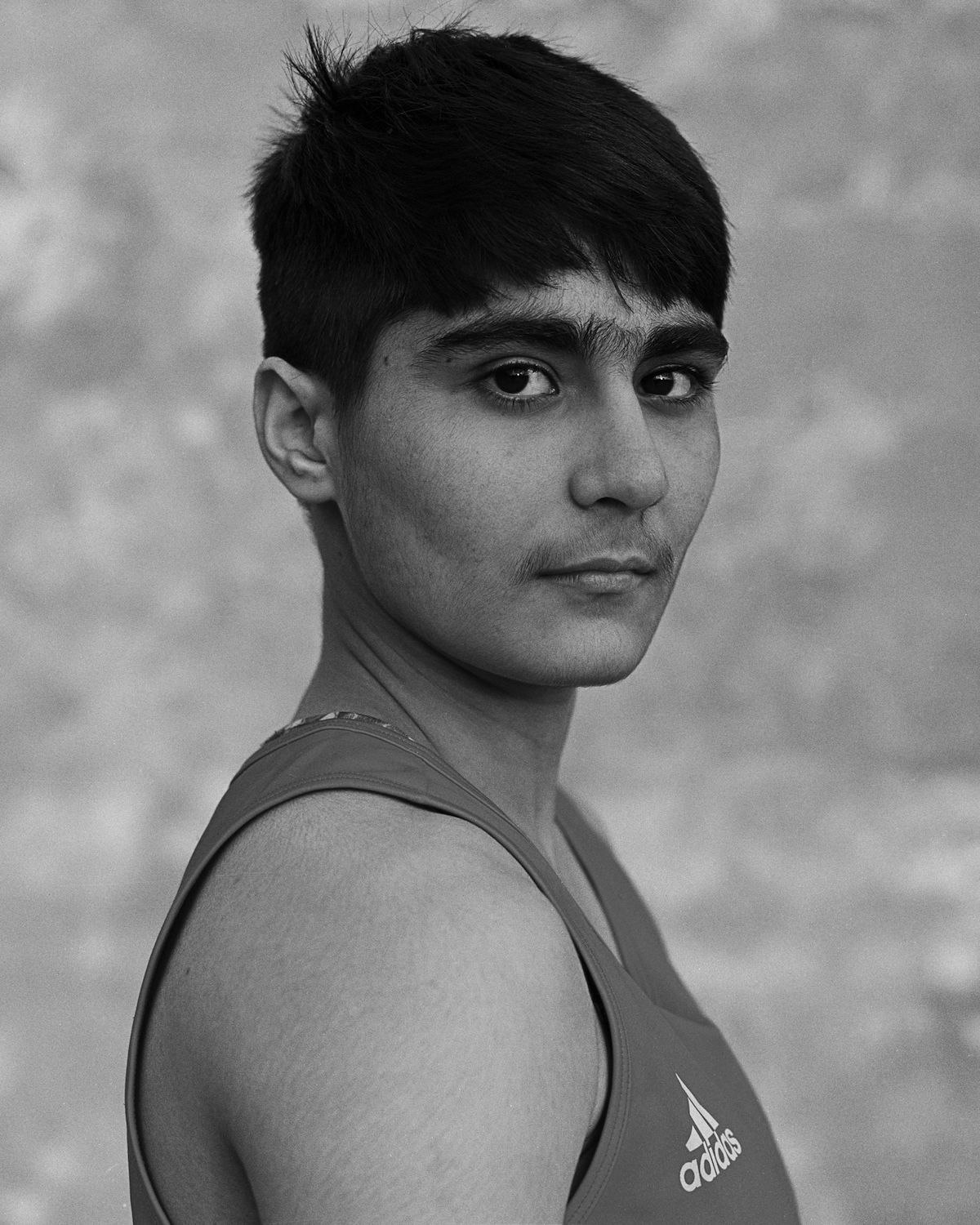

Prarthna Singh

The girls in Prarthna Singh’s Champion know hardship. Born in Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, the north-central Indian states which have some of the highest rates of female infanticide and child marriage in the world, safety and freedom is not a birthright. The project tells the story of a group of girls who, at the age of 14, defy their families’ expectations and begin long-term training at government-run sports camps. They are determined to win medals and change their destiny.

“From day one in India, your family is everything,” says Singh. “What society says about you is so important. There is a line in Hindi – ‘Log kya kahenge?’ – which means, ‘what will people say?’ As a young woman living in a deeply patriarchal society, you hear the phrase constantly. The line applies differently to men. Whatever men do – including sexual and domestic violence – there is always a way to justify it. Here in India, there is a continuous war against women.”

Champion – shot over the last six years – gives visibility to the physical and psychological landscape of Indian girlhood. Together, the wrestlers, boxers and judo players have formed a sisterhood, solidarity born from exchanging experiences, loss and the revolutionary act of pursuing their dreams. “These girls are fighting society, their families and notions of femininity that are instilled upon them since the day they were born. For them, even entering the ring – it’s a radical act.”

Singh’s portraits are serene. Her collaborators exude pride, returning the viewer’s gaze, full of self-assertion and beauty. The project charts their emotional trajectory converging ideas of gender and femininity with nation-building. The self-reflective images hold space for the rigour and determination of their daily labour while offering a transformative vision of hope and possibility for future generations. “Since 2015, when I first went to the camps, I’ve witnessed such powerful growth,” Singh explains. “When I first met them, they were insecure, shouldering a lot of pressure and desperate to prove themselves. As wider Indian society starts to recognise female athletes, the younger girls have more agency – finding different ways to build their identity free from shame and fear.”

Dorian Ulises López Macías

The threshold of public and private space can be fraught for queer people. Many of us have to leave parts of ourselves behind, remaining vigilant to the reality that it may not be safe. Through his vibrant practice, Mexican photographer Dorian Ulises López Macías explores notions of queer visibility set against his country’s sprawling cities. “I am part of this community,” says López Macías. “I am raising my voice for my people. It is essential to fight so that we all understand the importance and beauty of our existence.” There is profound poetry in his politics. The camera, for López Macías, is a portal; a tool that allows for freedom and acceptance while documenting a state of becoming.

The social conditions for LGBTQIA+ people vary across Mexico. Human rights are protected in large cities and states with progressive government officials, and there are legal ramifications for acts of anti-LGBTQIA+ violence. However, in states with conservative officials, hate crimes occur with impunity. The country’s values are also steeped in Catholicism and binary notions of gender. The traditionally macho culture creates a hostile environment for queer life. Despite this everyday reality, López Macías has seen significant changes in his lifetime. “With respect to my generation, I notice an enormous advance in terms of personal acceptance,” he says. “I perceive much freer humans, without so much prejudice. I can feel the transformation, and this generates and models pride for the next generation.”

López Macías’ work is rooted in curiosity. His collaborative practice – every project begins from a connection made on the street – is the lifeblood of his work. He disentangles the fraught psychic environment that impacts queer life, imagining his sitters in a state of ultimate joy and pleasure. In doing so, he introduces new modes of visual language that occupy the intersection of Mexican and queer life. “I realise the importance of what I’m documenting and its urgency,” he says. “I have always believed in the healing power of photography and the light that comes from it.” For López Macías, being seen is vital – a way to vision yourself into history.

Kwabena Sekyi Appiah-Nti

“I want to contribute to the self-image of Black boys,” says Kwabena Appiah-Nti, aka Sekyi. “If you are constantly seeing negative things about yourself, it influences you consciously and subconsciously. Through my imagery, I hope to invite Black youth to see themselves differently while encouraging them to document their own experiences and culture.” The Ghanaian-Belgian photographer, born and raised in the Netherlands, is building a practice rooted in consciousness-raising. His work expands the visuality of Black boyhood, dismantling harmful stereotypes and replacing them with images that embody beauty and freedom. “Photography allows me to make the ideal image,” Sekyi shares. “I’m interested in its possibility to take real people, places and feelings and ground them in a dream-like world.”

In 2018, Sekyi was on holiday in Itacaré, a small surf town in Bahia, Brazil. He photographed a boy on the beach with his hair painted gold. He did not think anything of it until he was back home editing. The image was an unexpected turning point in Sekyi’s practice. It illuminated his fascination with boyhood, a phase in life that is inherently unfixed and ripe with possibility. This awakening manifested as Golden Boy, an ongoing body of work that stretches across Brazil, Ghana, Suriname and France, among other countries. The warm and captivating images draw from his own experiences and that of his collaborators. He photographs Black boys in leisure and play: riding motorbikes, swimming in waterfalls and playing football on the beach. He finds his sitters on Instagram or wandering around the cities he visits. Taking time to get to know them enables him to present an authentic expression of their lives.

For Sekyi, the work unites the personal and political. He holds space to relive defining memories of his boyhood while challenging the historical and contemporary gaps in representation thinking about who is pictured? Who is doing the picturing? And whose stories are being told? Through the devices of imagination and storytelling, he conjures narratives of joy, camaraderie and fantasy. Golden Boy proposes a community – a vision of utopia – where the entire spectrum of Black boyhood is celebrated.