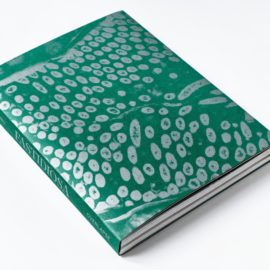

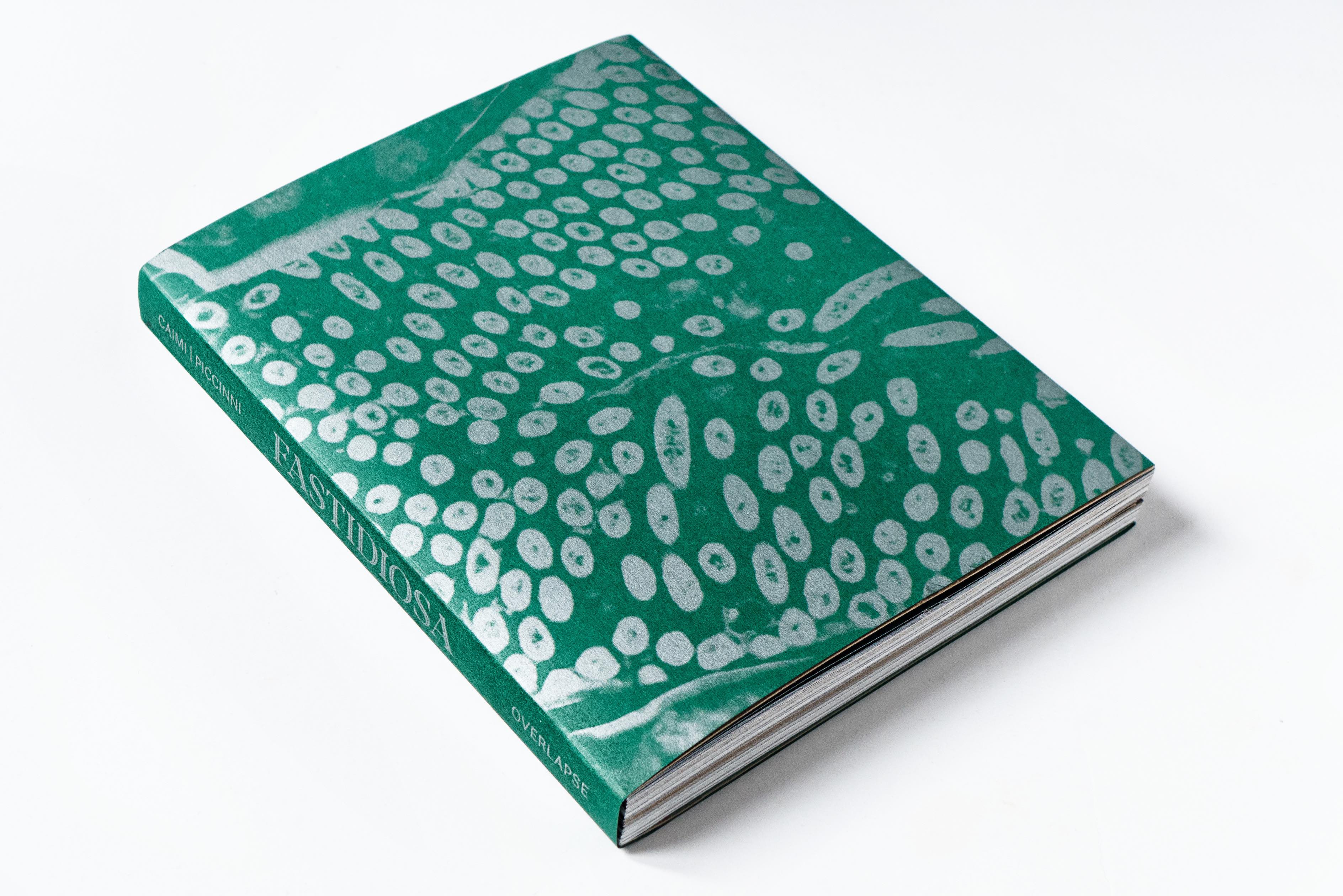

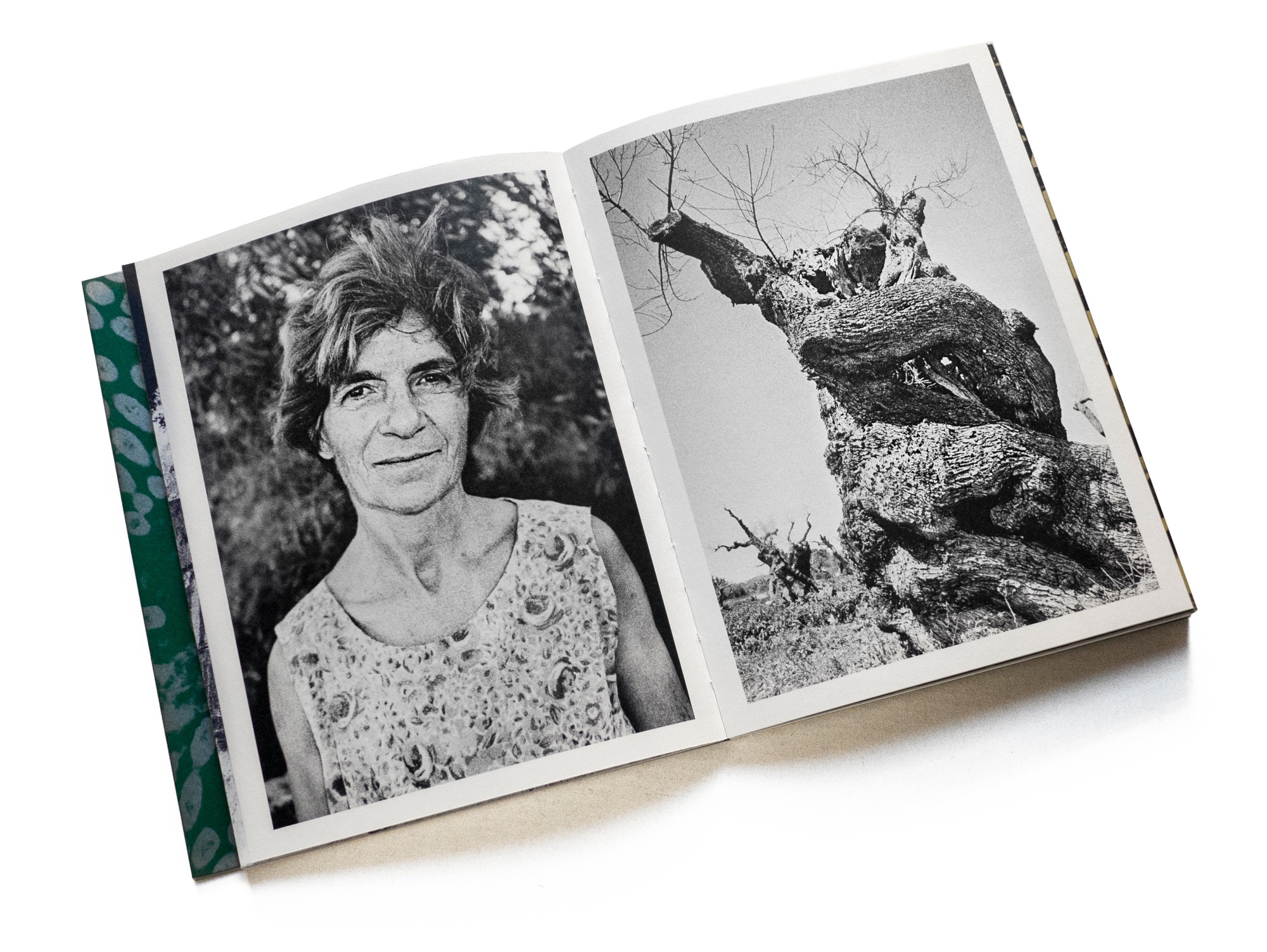

The threat of an aggressive disease ravaging the olive trees in Italy is documented in Caimi | Piccinni’s new book

The threat of an aggressive disease ravaging the olive trees in Italy is documented in Caimi | Piccinni’s new book

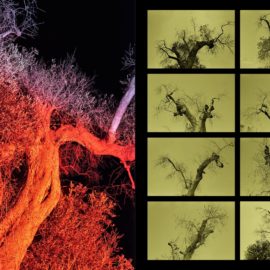

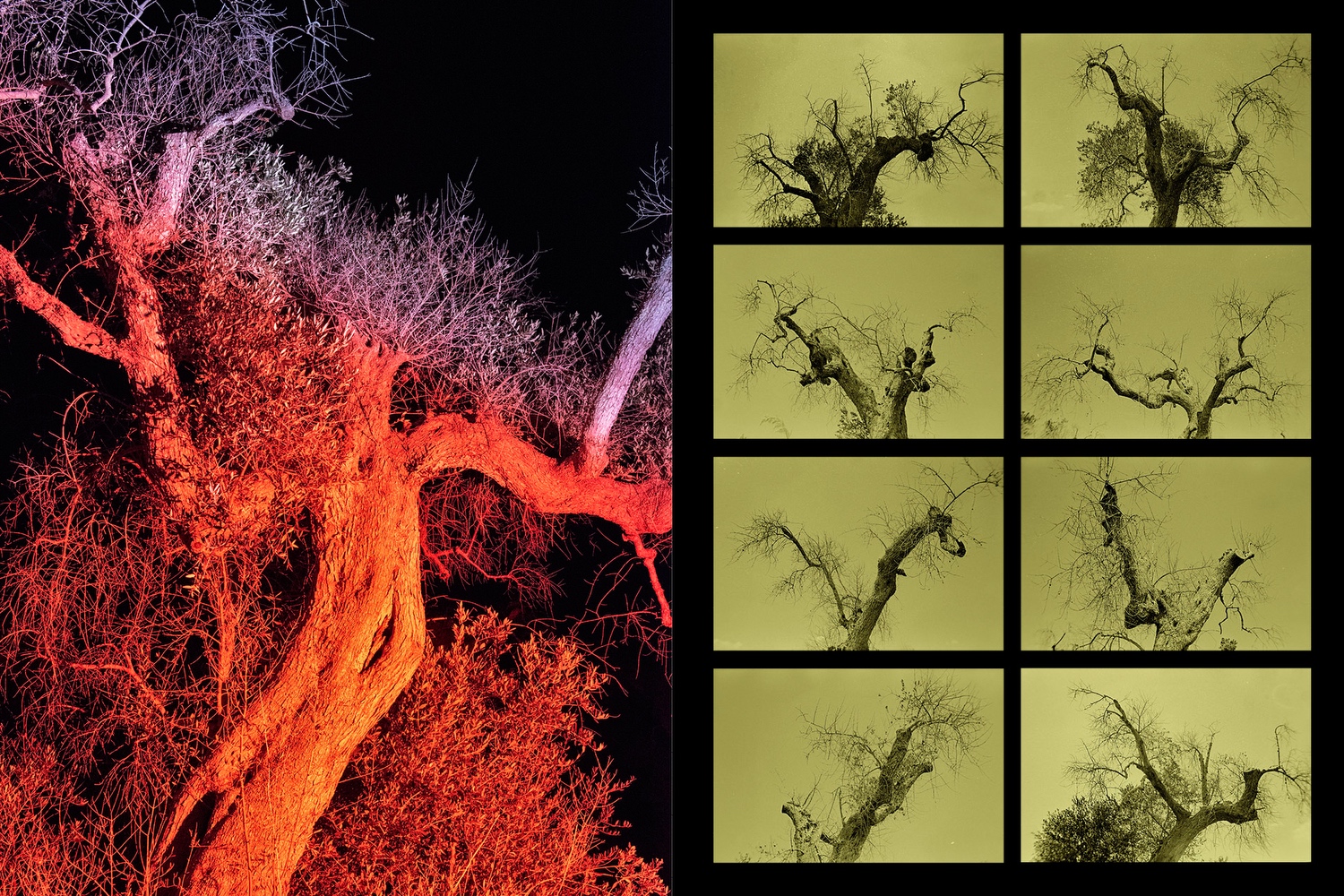

A nighttime inspection of abandoned fields in Spongano. Farmers are waiting for government funds for a strategy of replanting new and resistant olive trees or for a change of destination of the field, which so far has not been allowed.

Source:The threat of an aggressive disease ravaging the olive trees in Italy is documented in Caimi | Piccinni’s new book

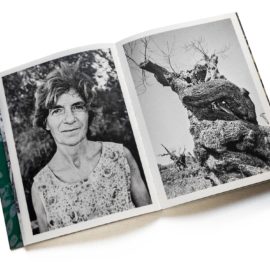

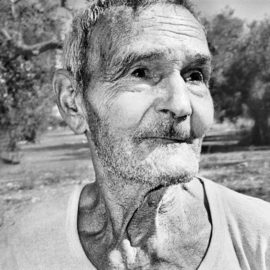

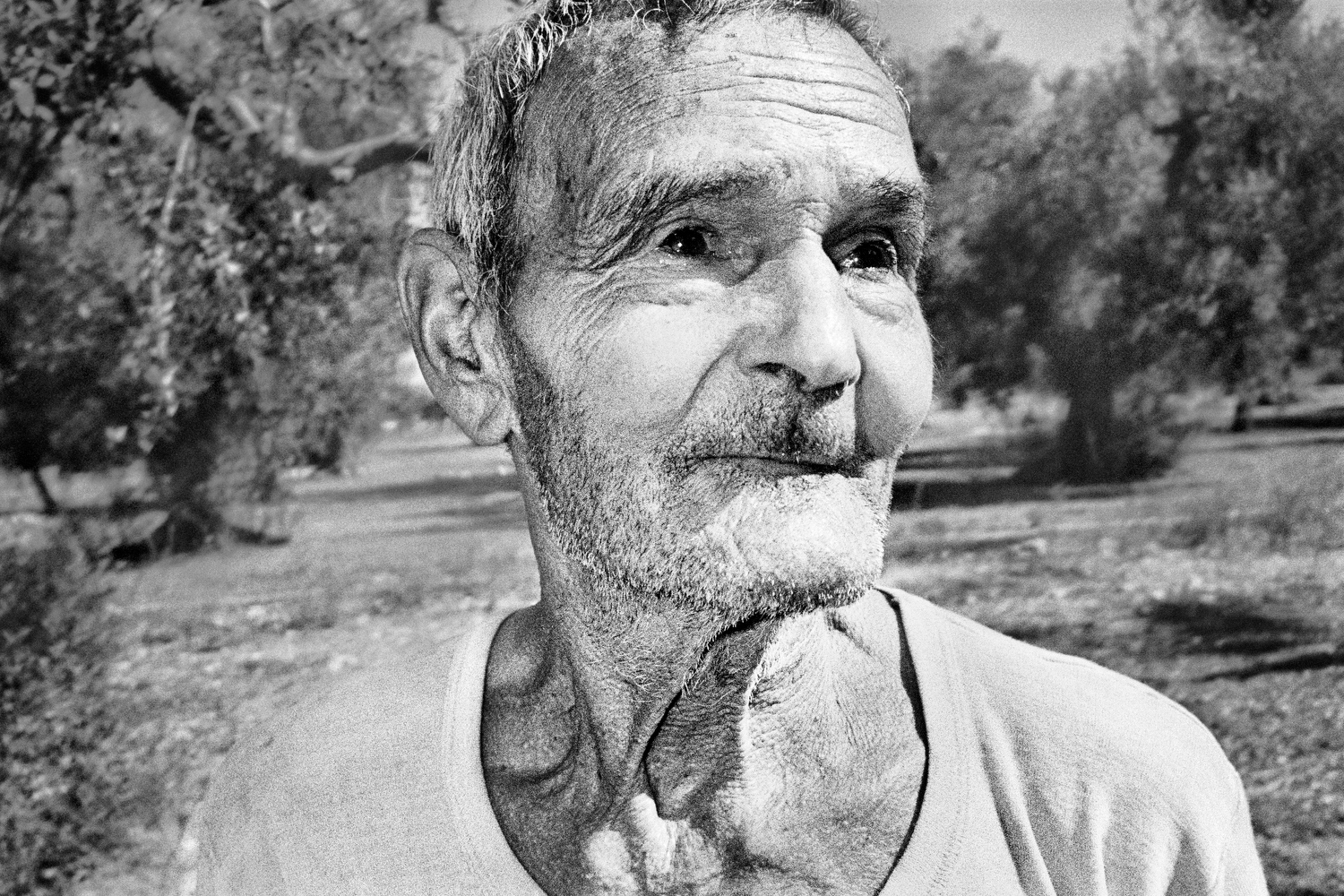

Rocco, 80, a farmer from Acquarica in Salento has his olive groves attacked by the xylella disease. He is desperate, as he lives only on the income from olive oil and his small pension of 500€. He said he wishes to die before all his trees do. 6 001

Source:The threat of an aggressive disease ravaging the olive trees in Italy is documented in Caimi | Piccinni’s new book

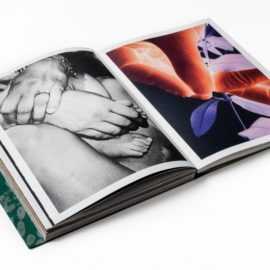

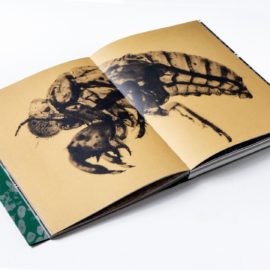

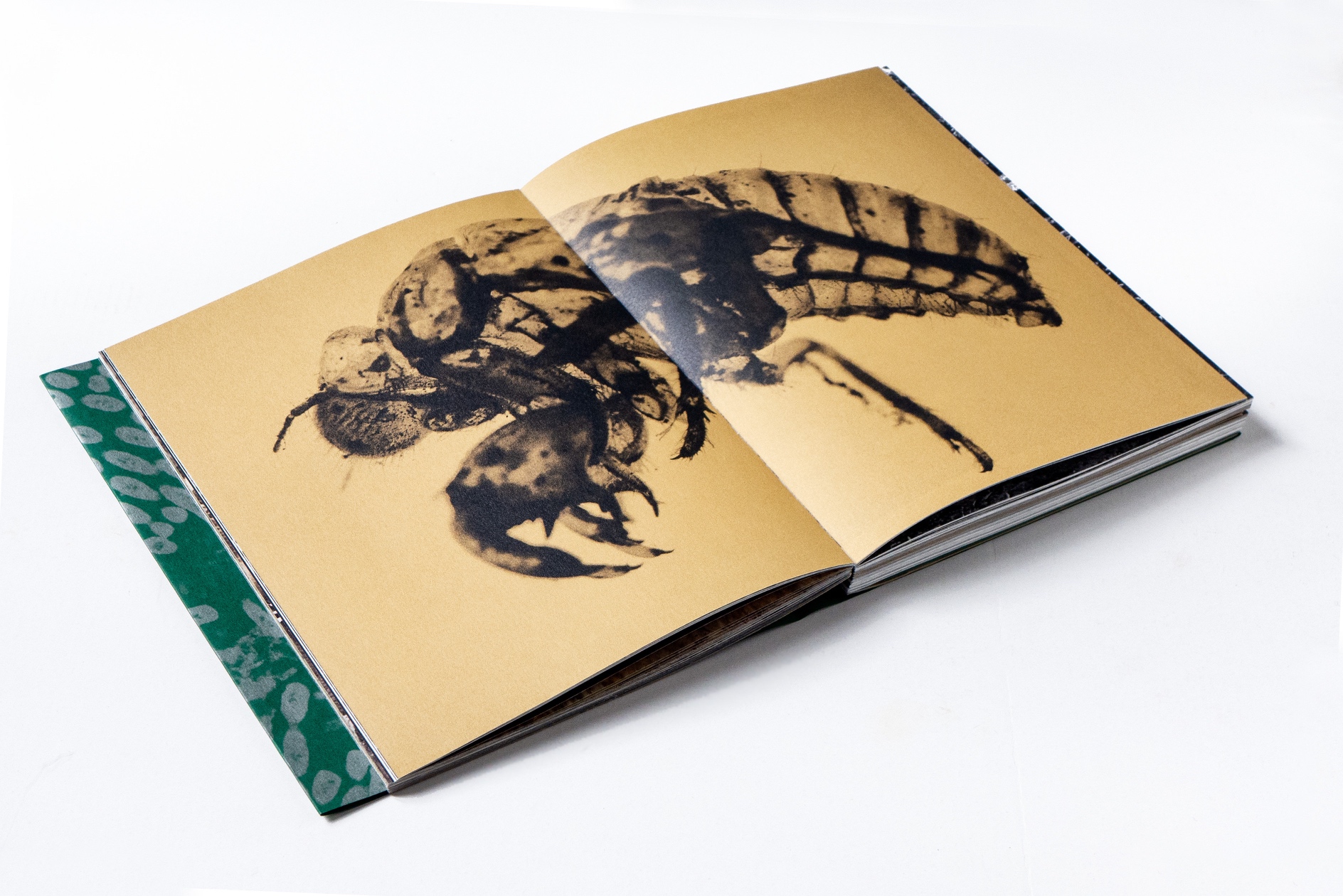

Specially prepared shoots of spontaneous olive xylella resilient trees are grafted into multi centenary dying trees. This experiment, run by agronomist Giovanni Melcarne is part of a larger project to find solutions to the xylella pest. According to his theory, the xylella bacteria is blocking the xilematic vessels of the branches but on a lesser extent the main tree body. Trees die by suffocation in absence of green leaves. Implanting xylella resilient new sprouts, there's a chance of saving the whole tree.

Source: