18 alumni from our first round of Fast Track are being represented at LE BOOK Coast to Coast in North America on Thursday 29 July. If you're an unsigned photographer, and want to have your work championed amongst global brand directors, advertising agencies and industry figures this September, enter Fast Track Vol. 2 now.

Vietnamese-born, London-based Thu Nguyen is one of the most respected agents in the business. Here, she reflects on the industry’s ongoing attempts to represent a broader spectrum of people

Thu Nguyen, director of CLM Agency (CLM), is one of the most respected photography agents in the business. Yet she remembers, as a young ambitious woman of colour at the start of her career in the 1990s, the regressive culture that pertained in professional photography and high-end fashion.

“It’s difficult to reconcile,” she says, of the way people in the industry used to routinely behave. “I joined CLM 18 years ago. I’m of the generation where, as a female, you accepted bad treatment [before my time at CLM]. The things certain people would say to you. How you were viewed. There was so much sexist stuff that happened, and a lot more than that too… It was normalised back then. It was expected… If you said anything, you’d be the person that couldn’t take a joke.”

But, in the space of a few years, Nguyen has seen a transformation. “The generation now, they’ve taken that thinking and turned it upside down,” she says. “They’ve said: ‘No, we’re not accepting this. We’re challenging it.’ And suddenly, our generation is thinking: ‘Oh my God, you’re so right!’ They’ve made it seem so simple.”

Nguyen is the top photography agent at CLM, which has offices in London and New York, and represents some of the leading young artists of their generation. CLM is also closely involved with the international photography and creative industry publisher LE BOOK, as well as Connections by LE BOOK, a custom-made trade-show for the creative community which has recently migrated to the online space with the launch of Connections Digital.

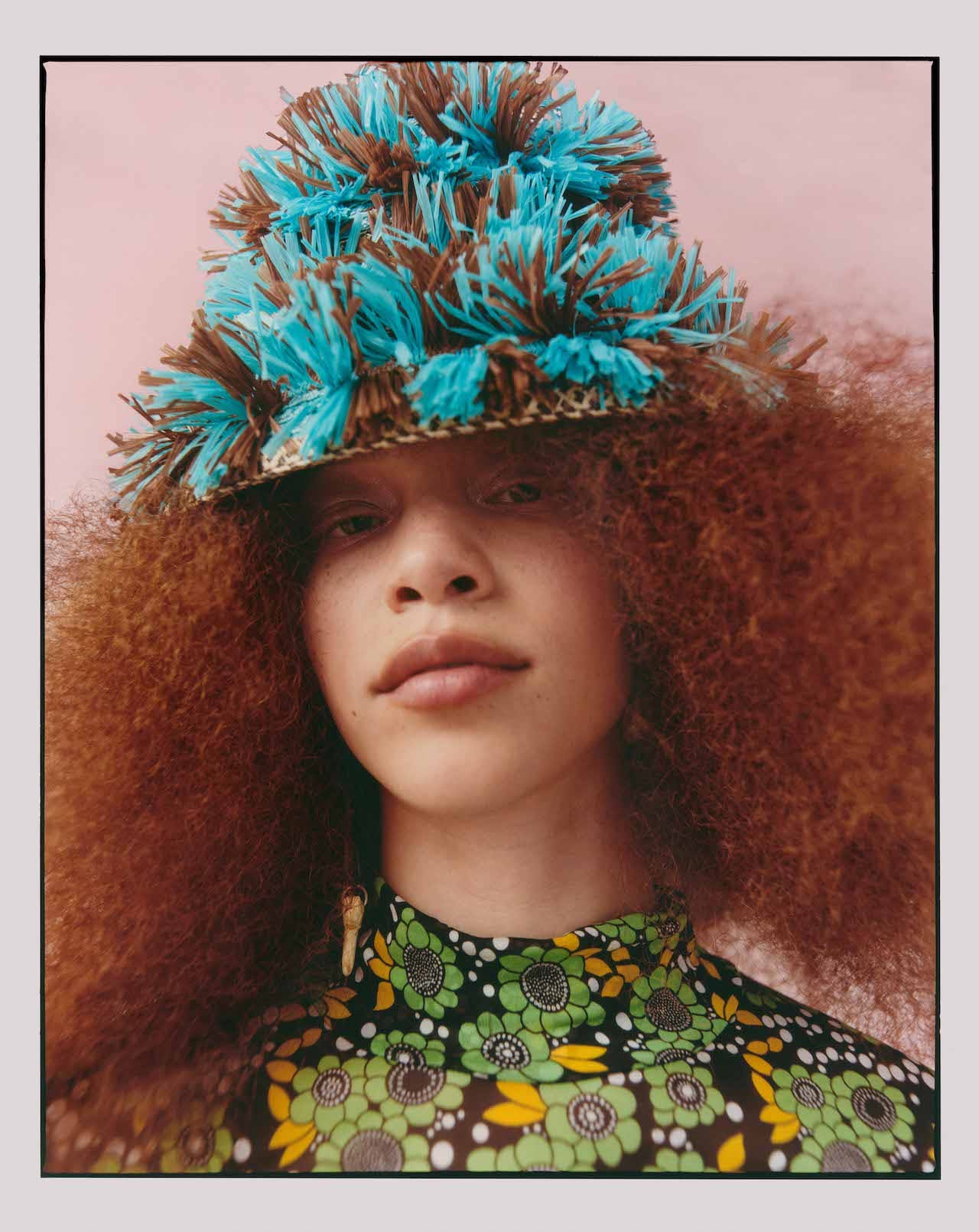

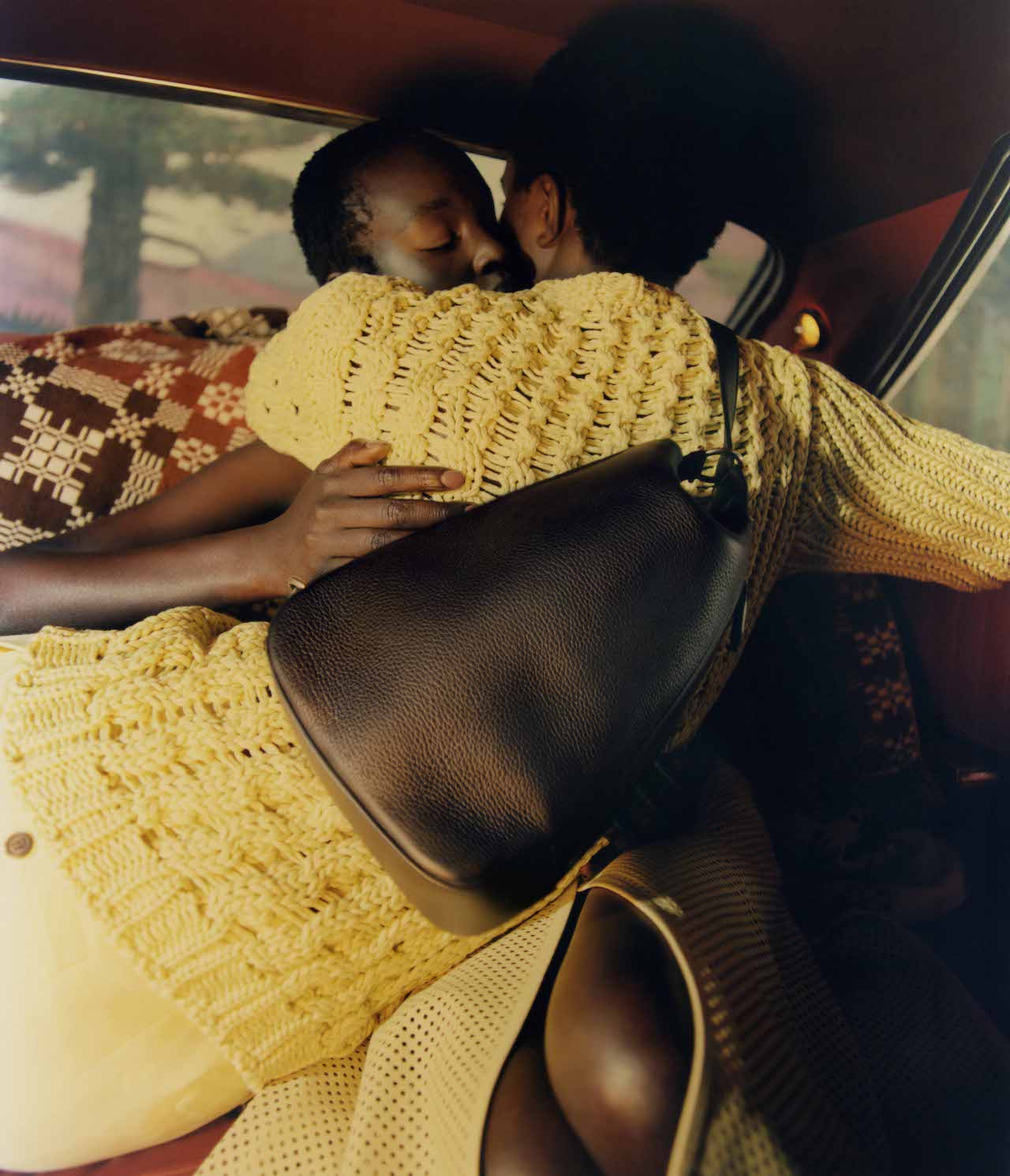

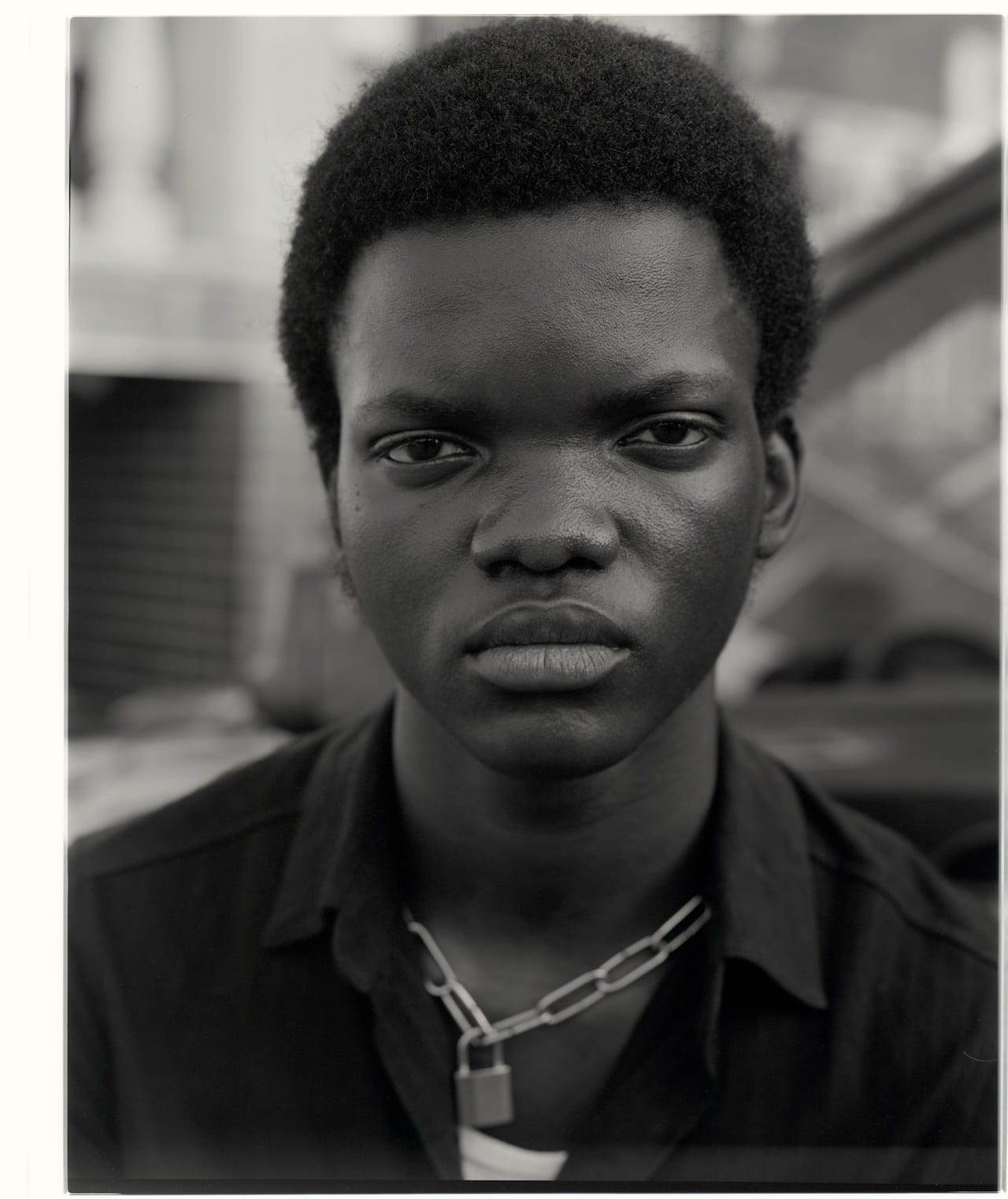

Its roster includes Campbell Addy, Lea Colombo, Davey Adesida and Nadine Ijewere, the photographer from south-east London of Nigerian-Jamaican parentage who, in January 2019, and at the age of 26, became the first photographer of colour to shoot a Vogue cover.

Ijewere signed with CLM shortly beforehand, in 2018. “[Nadine’s images] were really resonating with a lot of people,” Nguyen remembers. “I remember seeing this portrait of a beautiful Black girl holding these flowers on the streets of London. Nadine had called the series ‘Ugly’ – it was her interpretation of beautiful – and she had flipped the long-held industry view of beauty on its head. She was willing to really challenge the status quo of what is beautiful, and what can be beautiful. She was telling us: beautiful can be a lot more than the singular image we’re fed on a daily basis.”

Ijewere managed to place these images in Vogue Italia. Soon afterwards, the photographer found herself on set for the cover shoot of British Vogue, photographing Dua Lipa, Binx Walton and Letitia Wright on the Kentish coast, then working with Edward Enninful to translate the images across British Vogue’s pages.

As a young agent, Nguyen remembers the UK industry always selling a monolithic idea of beauty. “A lot of us grew up with one ideal of what beautiful is, and it was very Eurocentric,” she says. “That’s being broken down now… I have a daughter now – it’s so amazing that my child is growing up seeing different kinds of beauty; that’s powerful to me. And very important.”

Stories like that of Ijewere are increasingly common. The industry is changing for the better, and quickly. “But there’s still a long way to go,” Nguyen points out. “We now have people in positions of power who are engaged in these issues, but I think the change is being driven by the consumer as well. Millennials, and especially generation Z, have the desire to see themselves – and so they should. They want to see themselves reciprocated and represented when they pick up a magazine. I think people have always felt that way, but now we have a generation who are more confident in voicing it.”

Fashion is often seen as frivolous, Nguyen acknowledges. Art is seen as hermetic, elitist. The real-world impact of photography is often questioned or negated. But, if you’re young, not white, not well-off, not lucky enough to live in a global capital like London, Paris or New York, seeing parts of yourself and your life reflected in the media matters a great deal.

“Imagery is such a powerful tool. And to see yourself reflected in images, it makes you think you can be part of that industry,” Nguyen says. “It allows you to dream of one day being the photographer or the model or the stylist, and be part of an industry that is not just for others; that you too can be part of it.”

More than anyone, it’s those behind the lens that have driven this change. Nguyen thinks many photographers of colour may once have felt the urge to curb their own vision if they gained a big commission. They would have tried to appease the client’s wants rather than forging ahead with their own perspectives. It was an understandable thing to do, she says. But that urge to self-censor is being left behind.

“Ten years ago, the whole crew on a shoot would have likely been white or European. The model would have been white. To have an unknown model that wasn’t white would have been shocking or unusual,” she says. “As a photographer, if you showed a portfolio full of just Black or Asian models, then people wouldn’t have booked you. Now, you might get booked. Today, people would judge the quality of the photograph much more. And that’s a profoundly good thing.”

But is there a risk of an over-correction? After the death of George Floyd in 2020, and the mass, pan-national protests they sparked, a lot of organisations decided to demonstrate their anti-racism credentials. That meant a lot of direct action, and a lot of positive discrimination. Across fashion, journalism and photography, photographers of colour and under-represented creatives were being pushed to the front of the queue. For some of them, this in itself caused concern and unease. Were they getting opportunities because of their ethnicity rather than the quality of their work? Writing in The Times, artist Grayson Perry has outlined his thoughts as to why positive disrimination can serve to further embed systemic racism, using research from the London-based campaign group the Manifesto Club.

“I have always suspected that positive discrimination had a downside,” Perry wrote. “The artist and arts consultant Sonya Dyer, assisted by Josie Appleton, J. J. Charlesworth and Munira Mirza, has published a report called Boxed In about how cultural-diversity policies constrict Black artists. Racism is one of our greatest social evils. Boxed In outlines how in the art world it manifests itself in peculiarly convoluted and covert ways, often unnoticed by victim or perpetrator.”

“For us at CLM, when it comes to taking on artists, we always focus on the creativity in the work,” Nguyen says. “But we believe that the best ideas are brought to life by a diverse group of people.” Nguyen is a Vietnamese immigrant who arrived in London at the age of nine. “Speaking personally, I’m a person of colour,” she says. “And I’ve worked really hard to get to where I am. I’m an immigrant. I wasn’t born in this country. I worked really hard, and my parents worked really hard, to get here.”

Will the change endure? Are the shifts taking place now immutable, or could photography and fashion revert back to age-old ways? “I was asked this question by one of my artists,” Nguyen says. “Is it going to stay, or is it just a moment? I think it will stay, I hope it will stay and I hope we will continue to progress.”