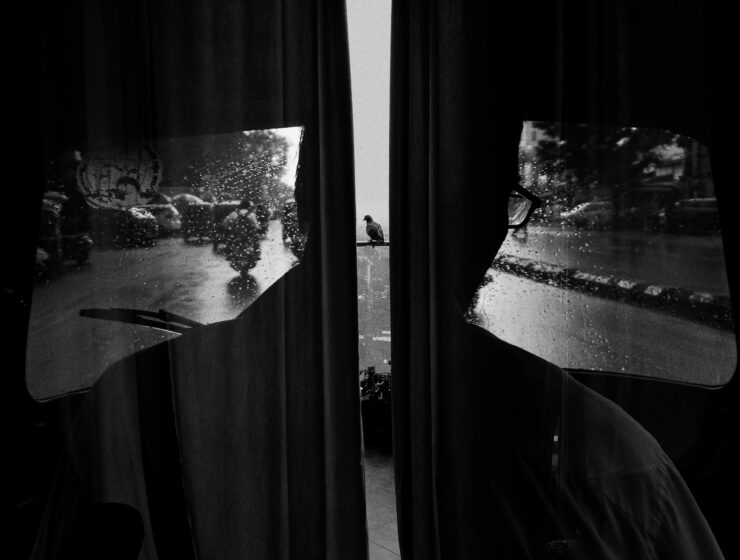

Photography by Teresa Eng

This article is printed in the latest issue of British Journal of Photography magazine, Activism & Protest, delivered direct to you with an 1854 Subscription.

For over five decades, the activist, photographer and artist has been creating photomontages that respond to the politics of the time. We visit his dynamic Hackney studio to find out more about his life’s work

“Art in itself doesn’t change anything,” says Peter Kennard. “But when it’s aligned to a political movement, it becomes its visual arm.” We are sitting in his east London studio, surrounded by posters and clippings of his political photomontages, created over almost five decades. From war and global poverty, to Thatcherism, austerity and the climate crisis, the 72-year-old artist has been commenting on injustices since his early twenties. “An image can get to people immediately,” he says. “Rather than keeping my work in the art world, it becomes part of the protest movement. And that movement needs visual work to get ideas across.”

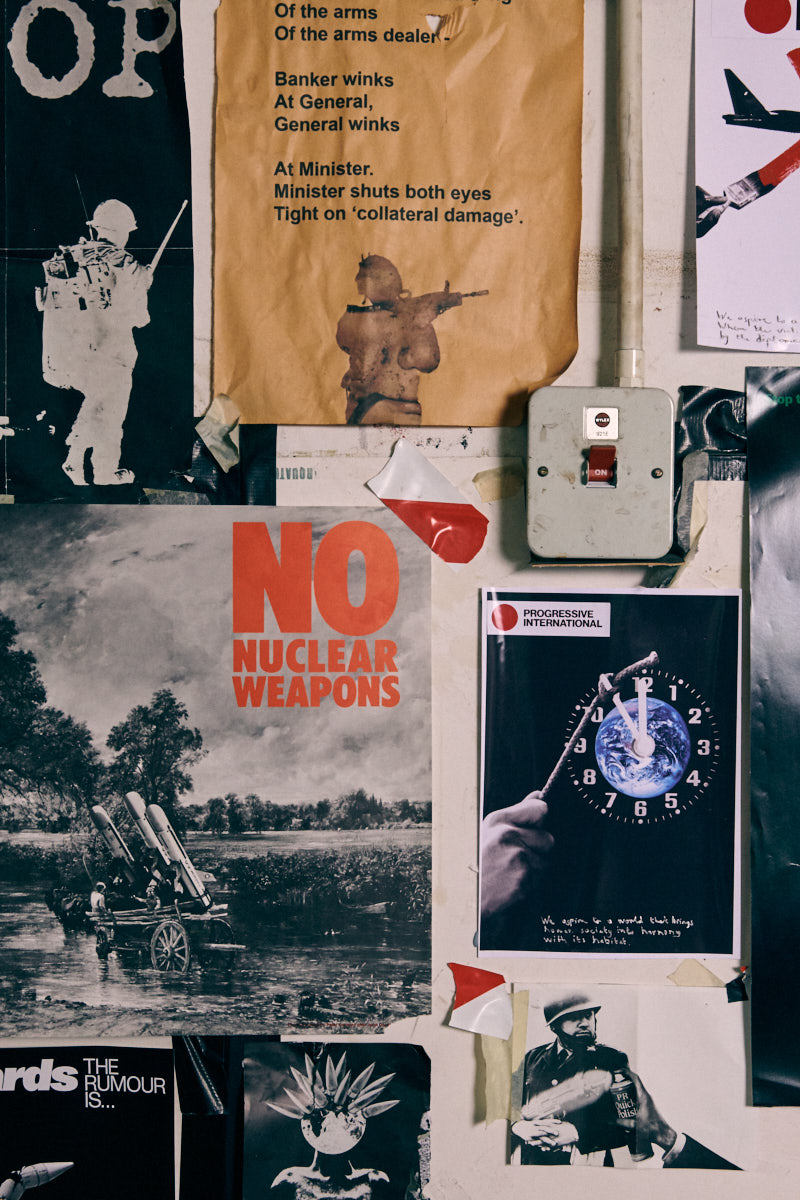

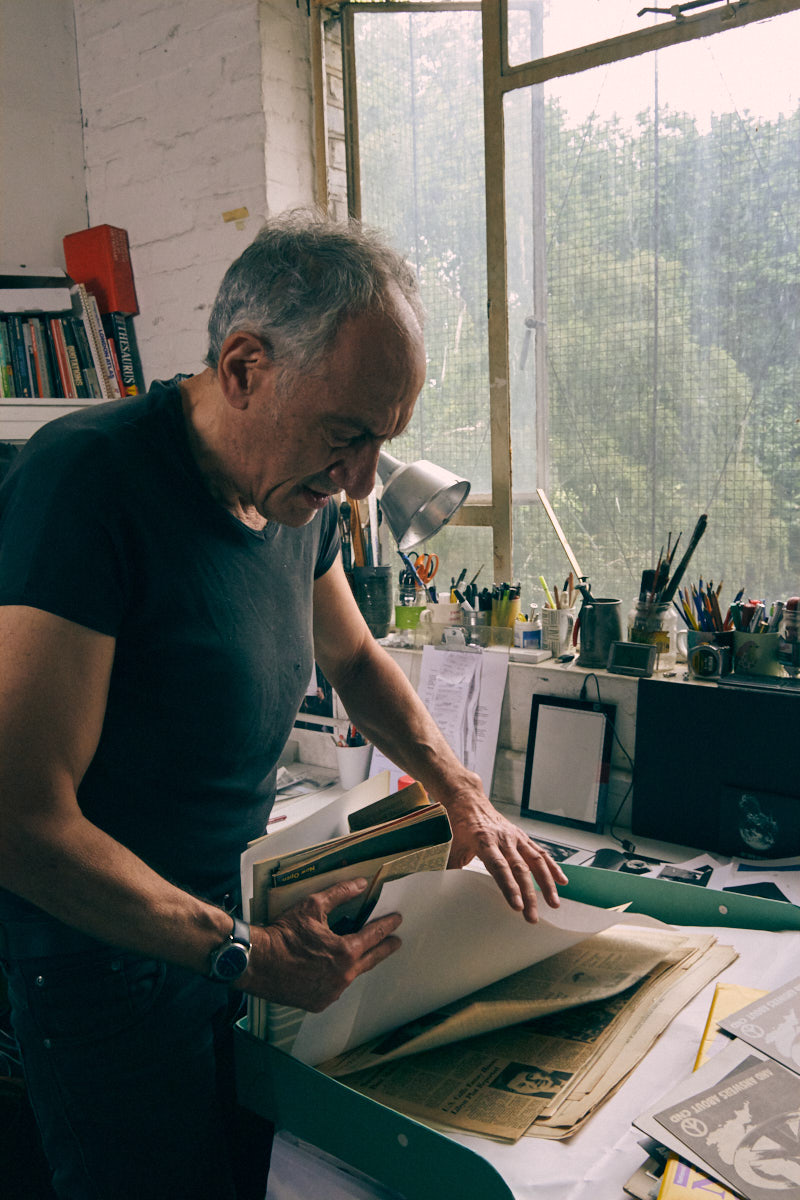

Kennard’s studio is located in London Fields, Hackney. When he’s not looking after his grandchildren or attending a protest, most mornings begin with a 30-minute walk from his home of 35 years in Stoke Newington, followed by two cups of black coffee on arrival. Photographs, posters and unfinished works are taped hastily across the studio walls, and pens and tools fill mugs lining the window sills. His collection of books and miscellaneous items – hats, loose wires, a typewriter – decorate the shelves. Kennard’s archive is housed in green boxes stacked from floor to ceiling. Here, he stores most of his original artwork; reproductions of his work in magazines, newspapers, posters and books, and documents relating to the causes he champions. “It’s not just an archive, in that sense, it’s social history,” he says.

“When I found out about the atrocities that were taking place in Vietnam, I wanted to find a way to make work that related to that. That’s why I started using photographs. I wanted to get away from work that had to be in the gallery, and I saw the leftist magazines and newspapers of that time as a good way to get my work out there.”

As well as being an artist, Kennard is professor of political art at Royal College of Art, where he has taught for 25 years. The studio plays an important role in both his practice and work life – especially when the pandemic forced education online. “It’s important to keep a working space,” says Kennard. “Even if I’m not coming up with a lot of ideas, it’s good to be around the materials, because suddenly something will click… You start thinking visually rather than intellectually. Everything is like a visual dictionary of ideas.”

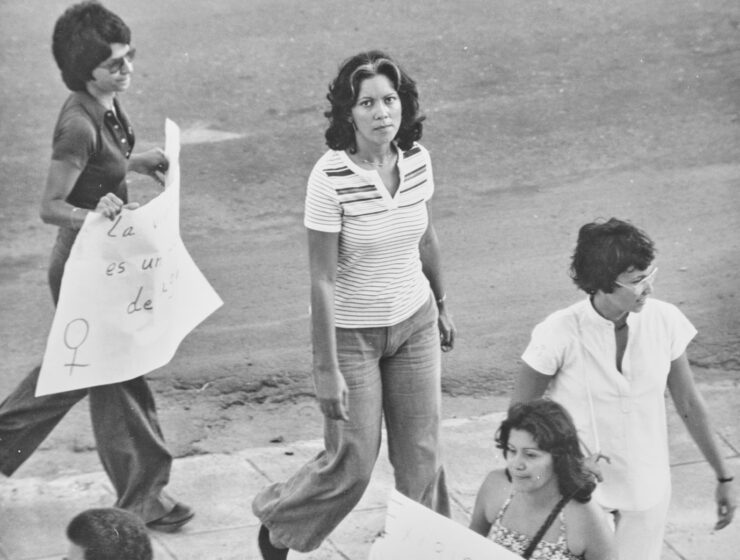

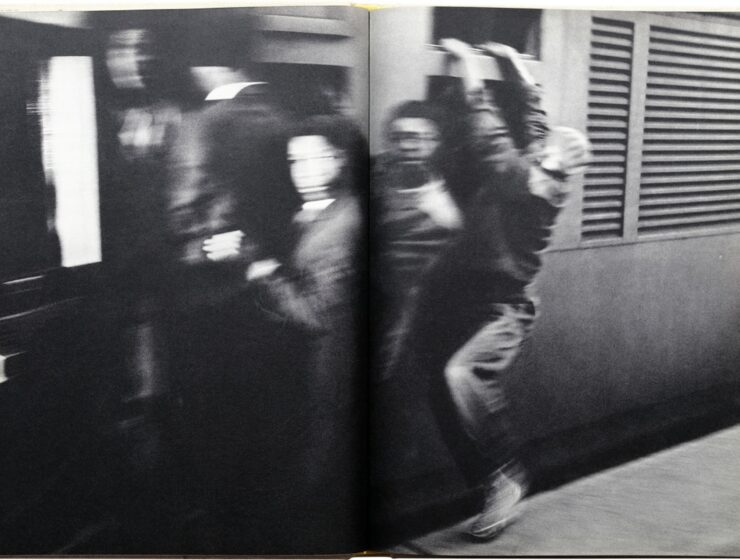

A lifelong Londoner, born-and-raised in Paddington, Kennard studied fine art at Byam Shaw School of Art then the Slade School of Fine Art. A turning point came during the anti-Vietnam War protests in 1968. “That’s when I became politicised,” he says. “When I found out about the atrocities that were taking place in Vietnam, I wanted to find a way to make work that related to that. That’s why I started using photographs.” Kennard freelanced for the left-leaning newspaper Workers Press, while living out of a Camden squat and working night shifts as a telephonist for the Post Office. “I wanted to get away from work that had to be in the gallery, and I saw the leftist magazines and newspapers of that time as a good way to get my work out there,” he says.

“Getting the message out to the people who are engaged in the struggles that I’m addressing has always been important. Photomontage is a public medium. It deals with images everyone’s seeing every day, but you’re putting them together in a way that shows what’s behind them.”

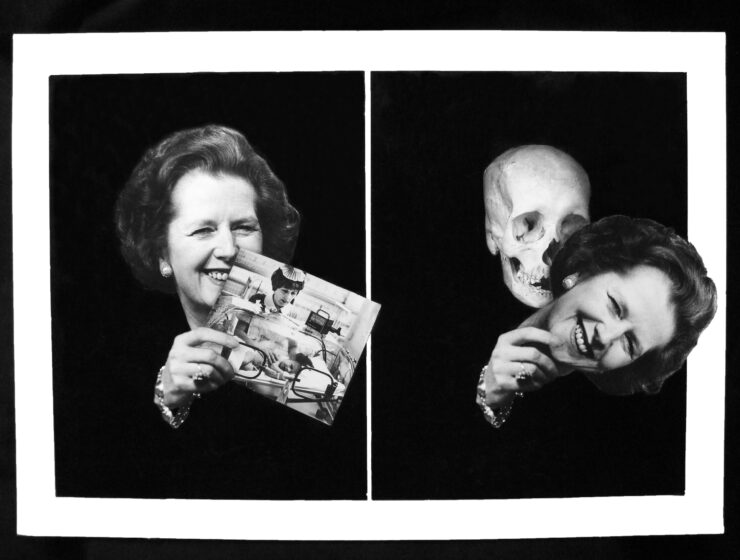

In the early-70s, there was no digital printing, photocopying and certainly no Photoshop. “I spent many hours in the darkroom, making different sized prints and cutting things up,” says Kennard. “A lot of these images are quite crude… I like the fact that you can see the breaks because they’re constructions and are not meant to look like reality.” Kennard sourced images from picture libraries, or magazines like The Sunday Times Magazine and Der Spiegel. “I see these photos as words that you form into sentences,” he says, gesturing to the images around him. “You put them all together, and it’s like creating a chapter in a book.”

Although the process is important, for Kennard the success of a final image is in its distribution. “The way they go out into the world is as important as the original,” says the artist, whose images have been used in The Guardian, New Statesman, NME, The Sunday Times and more. His photomontages have appeared on placards for global political movements, and illustrated the covers of books about the economy, welfare state and nuclear arms race. Among his most disseminated images are the iconic Broken Missile (1980), made for CND, and the series Stop the War (2003), created for protests against the invasion of Iraq. The success of this work hinges on visibility, but also accessibility. “Getting the message out to the people who are engaged in the struggles that I’m addressing has always been important,” he says. “Photomontage is a public medium. It deals with images everyone’s seeing every day, but you’re putting them together in a way that shows what’s behind them.” Many of Kennard’s pieces – particularly the anti-nuclear ones, and more recently his climate work – continue to be used by activist groups. For non-commercial use by NGOs and charities, or for demonstrations, all of Kennard’s works are free to use. But the success of such images is a “double-edged sword,” he says. “It means we’re still dealing with the issues that we were campaigning about 40 years ago.”

As he plans his retirement from teaching at RCA, Kennard is devoting his practice to the climate emergency. It has been almost 25 years since he made his first collage responding to global warming. Depicting a dystopic, barren land, it was a response to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, in which 192 countries signed an agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Since then, Kennard has continued to produce work that visualises the threats to our planet and has campaigned with the climate activist group, Extinction Rebellion.

“My generation had all these great hopes that we were going to change things,” he laments, “but it’s actually worse across the world now than it was back then.” Is he hopeful for the future? “Some days,” he says. “But one can’t live one’s life thinking nothing’s going to change. You have to keep going.” Kennard quotes the Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci: “Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” In other words, we must see the world for what it is, but have the courage and persistence to believe that we can overcome its challenges.

Code Red, a retrospective of Peter Kennard’s climate work, is on show at Glasgow’s Street Level Photoworks from 30 October to 19 December.