All images © Aria Shahrokhshahi

The Iranian-British artist spends time volunteering for NGOs as well as creating material for his Sketchbook series

Aria Shahrokhshahi joins our call shortly after leaving a bomb shelter – he is in Odesa, and tells me that currently, facing drone and rocket attacks from Russia, they have to take the sirens seriously. Shahrokhshahi is back in Ukraine after exhibiting Sketchbook Volume 2 at London’s Have a Butchers gallery in July 2024, a riff on his Volume 1 exhibition in 2023. Each Volume was simultaneously printed as a zine.

Shahrokhshahi began photographing in Ukraine in 2019 and started volunteering there after the war broke out in 2022, working for the NGOs Base UA and Livyj Bereh – a group based in Kyiv – rebuilding houses, assisting civilian evacuations and helping children who live close to the frontline. He is originally from Nottingham, with Iranian heritage, and initially went to Ukraine to comb around its underground tattoo and party scenes while taking photographs of post-Soviet buildings and Ukrainian society. He is now sober, but remembers drinking the “poshest cocktails for a fiver”. He never intended to document conflict, but returned to Ukraine after Russia’s invasion to continue photographing the community.

“I want to use [flash] to show the beauty in the normality of a place that is in such extreme circumstances”

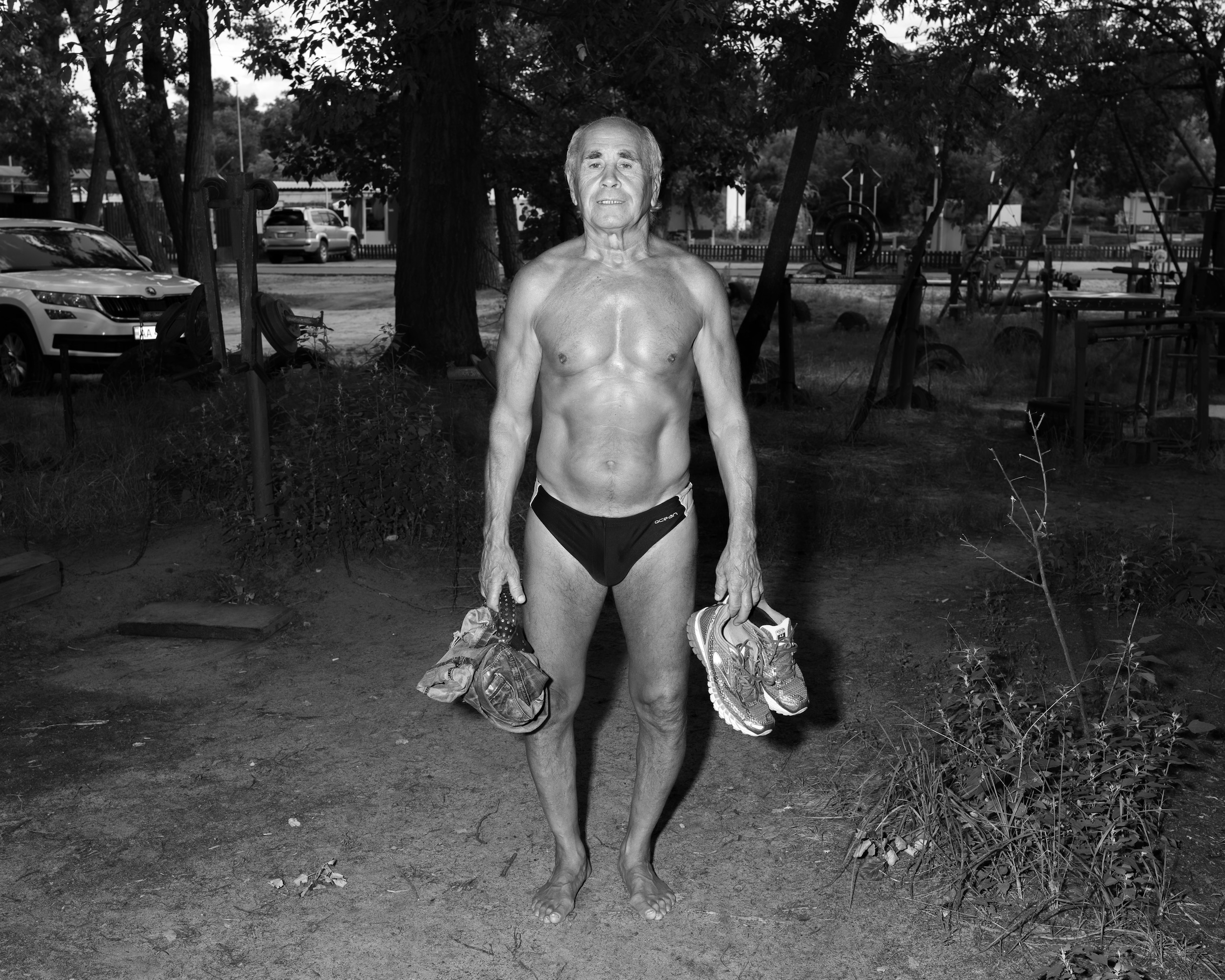

Interested in a sense of sovereign identity, the collective memory of space, and shifting ideas of masculinity, Shahrokhshahi is witnessing a nation which he says has been evolving for years. More people started speaking Ukrainian after the fall of Soviet rule in 1991; he was drawn to how different the culture is to that of Iran, where he previously spent a significant amount of time. Central to his Sketchbook project is the question of how to talk about violence without showing it; Shahrokhshahi used photography to work with an NGO addressing police aggression on the BLM movement, and documented in the Jungle in Calais, so he is acutely aware of the medium’s social justice impact. But he says: “I’m not a war photographer and I don’t want to be. It was just a place I was photographing, and the people I built a connection with happened to be at war.”

In one image, a young couple are intertwined in an intimate embrace, their skin glowing under the flash and seemingly melding into one. In another scene, a ballerina could be mistaken for a statue as she balances on pointe, alone on a vast, dark stage. Although the images are not direct depictions of conflict on the frontlines, the effects of war are very much present. One image shows a hare seen through the crosshairs of a sniper rifle. Another image, with inverted tones, is of a raging fire escaping the windows of a burning house.

Shahrokhshahi “wishes [he] had a good answer” as to why he photographs in black-and- white, but 4×5 film was cheaper in monochrome, so when he carried on with the work, he kept this format for continuity. “In terms of photographing a conflict, stylistically, I work with a flash because I’m interested in a sort of press approach to the work, and the way the flash isolates and normalises things. I want to use it to show the beauty in the normality of a place that is in such extreme circumstances,” he says.

Shahrokhshahi cites Nigel Shafran’s images of his kitchen sink in the Washing-up series, which were shot with a similar sensibility. “That sounds so boring. But it makes you feel something,” he says. He also notes Some Say Ice by Alessandra Sanguinetti and Deep Springs by Sam Contis as references, for work which documents but moves beyond potentially stale photojournalism. Now he is in the final phase of the series, wrapping up Volume 3, in which he focuses on identity and land. It will be released in spring next year.