All images © Yorgos Prinos

The Greek photographer’s latest solo show blends his photography with found imagery to create an actively critical voice, Phin Jennings finds

I wander thro’ each charter’d street,

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

— William Blake, London

In 2003, the New York Police Department discovered and captured a tiger living in a fourth-floor apartment in Harlem. Construction worker Antoine Yates had kept Ming, the 425-pound Bengal, since he was a cub. His existence became a local urban legend, one that was confirmed when Yates visited his local emergency room with bite marks.

Prologue to a Prayer, Greek photographer Yorgos Prinos’ recent exhibition at Hot Wheels London, included a dramatic photograph of Ming’s capture. Taken by photojournalist John Roca, it features a police officer suspended outside a window with a gun in one hand. On the other side of the glass, Ming lunges at him with bared teeth.

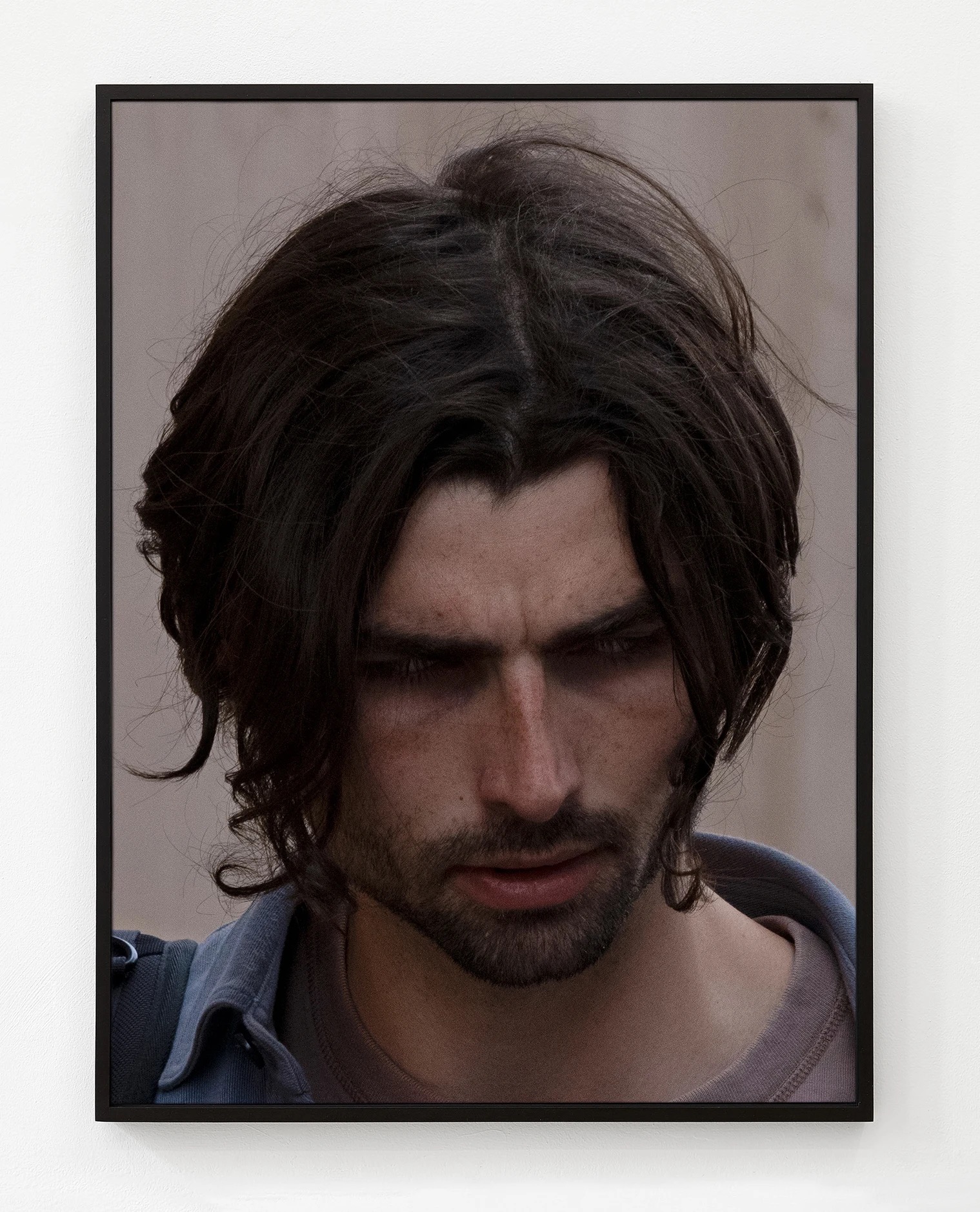

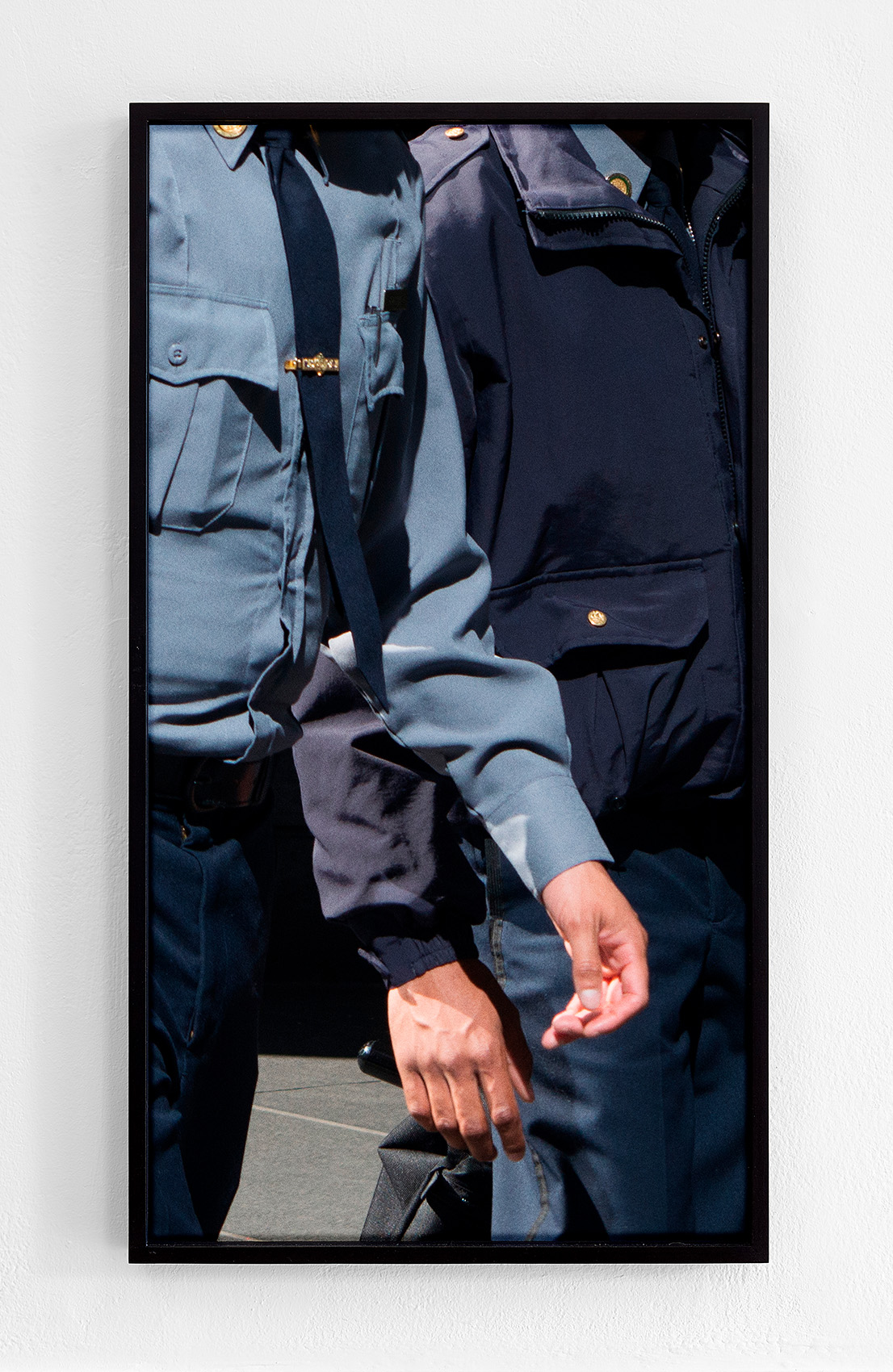

If this borrowed image is the violent climax of the exhibition, the photographs taken by Prinos himself present a more sedate storyline. One room contains a series of nine closely-cropped images of anonymous men navigating equally anonymous streets, their eyes fixed downward on their phones. Elsewhere, a group of nine boys form a Last Supper-like arrangement in New York’s Bryant Park, the two central figures captured in an anguished embrace. His photographs are always completely candid, taken without the subject’s knowledge, and almost always set in the world financial centres of New York and London. Though Prinos lends these scenes a certain gravity — the way that he contrasts deep, obscuring shadows with the clarity of sunlight somehow loads every moment with meaning — they are unremarkable beats in the city’s daily rhythm.

“Prinos requested that I avoid quoting him, reluctant to have an authoritative explanation of his work committed to the record”

This combination of quotidian urban subjects with journalistic photographs of shocking scenes is typical of Prinos’ work. He draws our attention to the fact that his protagonists – recognisable and unremarkable figures, anonymous enough to be relatable – live on the same surface of the same world as unreal-feeling stories like Ming’s. Mark Twain’s idea that life is stranger than fiction is an often-repeated one. Prinos is fond of a similar quote attributed to French film director Robert Bresson: “the supernatural in film is only the real rendered more precise.” The tiger’s apartment isn’t an imaginative story; it’s a short subway ride away from the boys in Bryant park.

The images that Prinos chooses to display alongside his own photographs often depict political moments such as the 2011 Egyptian revolution, a brawl between politicians in Ukraine’s parliament and Iraqi military operations against the Islamic State. In our globalised world, disturbing events like these don’t simply coincide with the daily lives of London and New York — they are, directly and indirectly, connected. In Modern Love (or Love in the Age of Cold Intimacies), an exhibition at Athens’ National Museum of Contemporary Art (ΕΜΣΤ), small photographs of such events were displayed in a parallel row below Prinos’ street portraits. Formatted as footnotes, their unfamiliar and often upsetting stories were presented as being inextricably linked to the exhibition’s surface-level subject of daily urban life in global financial centres.

The surface is an important place for Prinos, and he views the content of his own photographs — the faces and bodies of a city’s inhabitants — as being far from neutral. If the found images serve to tell us something about the condition of the world that we live in, the very same condition is reflected on these faces. The footnote-like images might be more immediately striking but, presented in relation to them, his everyday scenes carry an intensity of their own. From them, a certain malaise emerges: an anxiety. Small gestures — a blink, a sideways glance, a hand rubbing a face or placed on a shoulder — become soaked in meaning. The city begins to hum with significance, the anonymous figures that occupy it becoming vessels for something greater.

It’s difficult to say exactly what that something is; whether it’s an indictment for abuses of power by those who shape our world, a more general anxiety about the human condition or something else entirely. Though Prinos is a political artist, he’s no didact. He would rather let his images bring about a mood in his viewer than tell them exactly what they mean to him. He purposefully leaves gaps for us to fill in. That’s why his voice is notably absent from this feature; though we spoke a number of times during its writing, he requested that I avoid quoting him, reluctant to have an authoritative explanation of his work committed to the record. He was often more interested in hearing my own answers to my questions about his work than offering his own, leading to a conversation that ran in two directions. This is the kind of conversation he’d like to have with his audience, rather than a one-way flow of information and ideas from artist to viewer.

Whilst a painter starts with a blank canvas, encouraged to build from scratch a world of their own within it, a photographer begins with what’s already there. Prinos’ act of creation is one of cropping and compiling — deciding which aspects of the world to show us and how to put them together. The story that he tells is a disjointed one: it cuts back and forth between the streets of London and New York and the sites of historical moments; between business as usual and the far reaches of what is possible. There’s a complex network of dynamics that underlies these images and the relationships between them. Prinos isn’t interested in expanding on the exact nature of such a network or how we should react to it, but reanimates the world by giving us the sense that it is there.

The world is an ecosystem that supports the everyday lives of us, those that we love and countless strangers alongside acts of personal and political violence that stretch the limits of our imagination. It is an apartment full of tigers. Yorgos Prinos is here to remind us of this simple fact.