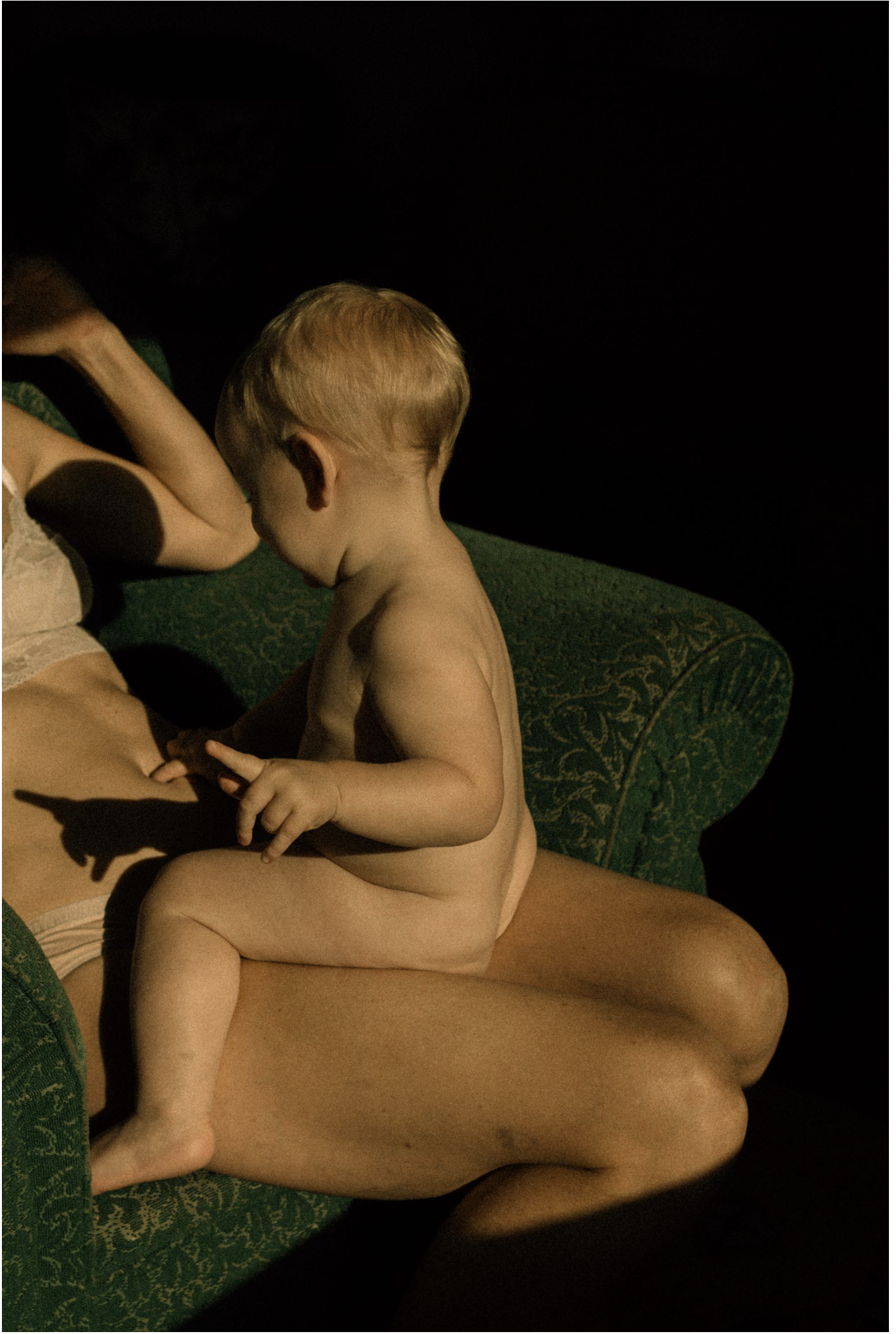

Proof Kids Are in Bed Text, 2015, printed 2024. From the series Surface Tension © Tabitha Soren

A new show at Princeton University Art Museum suggests the physical, the intimate, and the lived as key concerns in photography and culture

“We thought it was an interesting topic but what struck me was, when we took the first people round, some of them were tearing up!” says Susan Bright of “Don’t we touch each other just to prove we are still here?”: Photography and Touch, an exhibition she has co-curated with Susannah Baker-Smith which recently opened at Princeton University Art Museum. “It was quite emotional, which I don’t think we had anticipated at all.”

Photography and Touch is a show about physical connection in images, which includes work by 13 artists – from Lisa Sorgini’s intimate portraits of motherhood to Clifford Prince King’s shots of queer safe spaces, and Carolee Schneemann’s Meat Joy, a performance and film in which naked participants cavort with raw fish, chickens, sausages, wet paint, and plastic.

The exhibition was conceived during the Covid pandemic and the many restrictions that limited physical interaction. Bright and Baker-Smith believe that that period is one of the reasons the exhibition is provoking such a strong reaction. “I think there is a lot of unprocessed emotion around Covid,” Bright says. “Suddenly not being able to touch – and that idea of embodiment and how it affects your idea of identity – became really powerful.”

“Our bodies are the medium through which we perceive everything”

Bright is an independent curator who has worked with institutions such as Tate Britain and the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago; Baker-Smith is a psychotherapist, who is particularly curious about the body and its impact on our perception. “I’m interested in philosophers such as [Maurice] Merleau-Ponty, who explores what it means to be embodied and what it means that we perceive things through our bodies,” she explains. “Our bodies are the medium through which we are in the world and through which we perceive everything. When that was interfered with during Covid, it had profound psychological effects beyond what we could envisage.”

It’s easy to see how these factors play out in their curation. Sorgini’s images of mothers and children show close physical relationships which, if anything, became even closer during Covid. Sayuri Ichida’s Absentee suggests how touch, or the lack of it, intensified during this period. Her delicate book lyrically charts her loneliness during quarantine, and how her long-suppressed grief for her deceased mother suddenly emerged. Other works in Photography and Touch pick up on sensation in different ways, with Prince King’s photographs Safe Space and Poster Boys showing intimacy within queer communities of colour, havens interrupted by the lockdowns and closures.

But as these examples suggest, Photography and Touch also picks up on other contemporary concerns. The pictures of motherhood highlight a strand of image-making once underrepresented but now more fully acknowledged, as women’s experiences start to be taken more seriously. As Bright points out, when she curated Home Truths: Photography, Motherhood and Identity at The Photographers’ Gallery in 2013, it felt radical. Ten years later, such work has become more popular. Similarly, Prince King’s images speak of queer intimacy but also the experience of inhabiting a Black body in the USA, narratives that have also started to be better acknowledged, post-Black Lives Matter.

Other works suggest contemporary concerns over touching and consent, be it the #MeToo movement or wider sensitivity to embodied power dynamics. Richard Renaldi’s series Touching Strangers shows individuals in close contact who actually don’t know each other, for example; at first sight intimate, on closer inspection these photographs suggest something ‘off’ or slightly awkward, yet also the human desire for contact. Joanna Piotrowska’s staged images play with familiarity, meanwhile, but have a sinister edge, while Melissa Schriek’s Ode videos speak of tactility in an often underestimated relationship – friendship.

The latter is appropriate for Bright and Baker-Smith, who are friends as well as co-curators; they met through a mutual acquaintance in Paris then “just stayed in touch”, as Bright puts it. The pair set up an Instagram account called commonplace on which they exchanged photographic ideas online, then during Covid found themselves living in the same London neighbourhood. Their friendship, and the idea for this show, was cemented on long walks in Hyde Park, when such exercise was one of the few accessible activities. “I think we established that we really enjoy bouncing ideas off each other,” says Bright. “Susannah isn’t a photo person [as her practice is in another field], so she has a completely different set of references and that’s great.”

Bright says this dialogue was fostered on Instagram as well as in-person though, and that interaction highlights another contemporary concern in the show – the haptic quality of photographs, particularly now that so many are seen online and on-screen. Photography and Touch includes Tabitha Soren’s series Surface Tension, for example, which shows the fingerprints and swipes left on the screen when images are viewed on an iPad. The work was inspired by Soren’s own experience, when her daughter emailed a snap of herself puckering up, rather than kissing her mother goodnight in person.

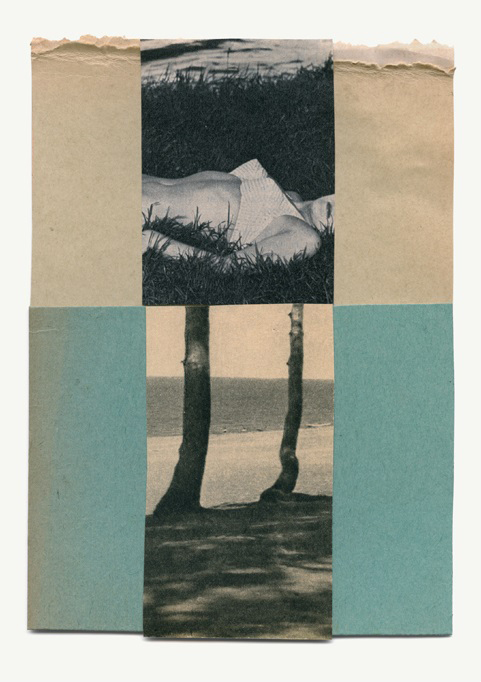

As Bright points out, turning the pages of family photo albums once also involved physical touch, and some of the other works play with materiality of print images. Katrien De Blauwer’s collages mix tactile materials such as old photographs, magazines, fabric, and tissue paper but are displayed behind glass to evoke “the distance we try to keep from each other and the absurdity of trying to force closeness”, the artist says. Patrick Pound’s collection of found photographs shows people cuddling up to animals, meanwhile, but his display also pins up prints and postcards – the latter handled by many during their manufacture and journey through the mail.

Odette England’s In the Black, In the Red also relied on the mail, as well as a kind of family photo. Shooting images of farmland once owned by her family then lost to bankruptcy, she folded the negatives along the old property lines, then sent them to her mother. Her mother stitched along the folds, then England printed the images and resewed the lines with red threads, the ends of which hang out of the photograph and the frame. “Everybody [in the gallery] immediately wanted to touch them, the people hanging in the show were getting freaked out,” chuckles Bright.

More radically, the exhibition also suggests images evoke something physical even without tactile interaction: Merleau-Ponty emphasised that both sight and touch exist within the body, explains Baker-Smith, and are therefore inextricably linked. “We tend to think ‘How can you see touch?’ but you feel it,” she reflects. “It isn’t just a kind of intellectual looking. That’s what is interesting to me, that people do have an embodied experience to a visual object.” The title of the show perhaps plays out something similar, as it is drawn from Ocean Vuong’s intimate poem, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. Words can also be physically moving, as anyone who has ever been moved by a book knows.

And this interest in the embodied suggests another contemporary theme, the vogue for the personal and the autobiographical. Art, literature, culture, and even politics are now putting more emphasis on direct ‘lived’ experience and subjectivity, while mainstream ‘objective’ narratives are being questioned (perhaps also encouraged by Black Lives Matter and #MeToo). For their part, Bright and Baker-Smith frame Photography and Touch in terms of exploration, rather than proposing it offers a neat or universal message. “It’s so crucial taking away those overarching curatorial, didactic ways of looking, they just seem really old fashioned,” Bright concludes. “That feels like a really important contemporary shift.”

“Don’t we touch each other just to prove we are still here?”: Photography and Touch is on show at Princeton University Art Museum’s Art on Hulfish gallery until 04 August