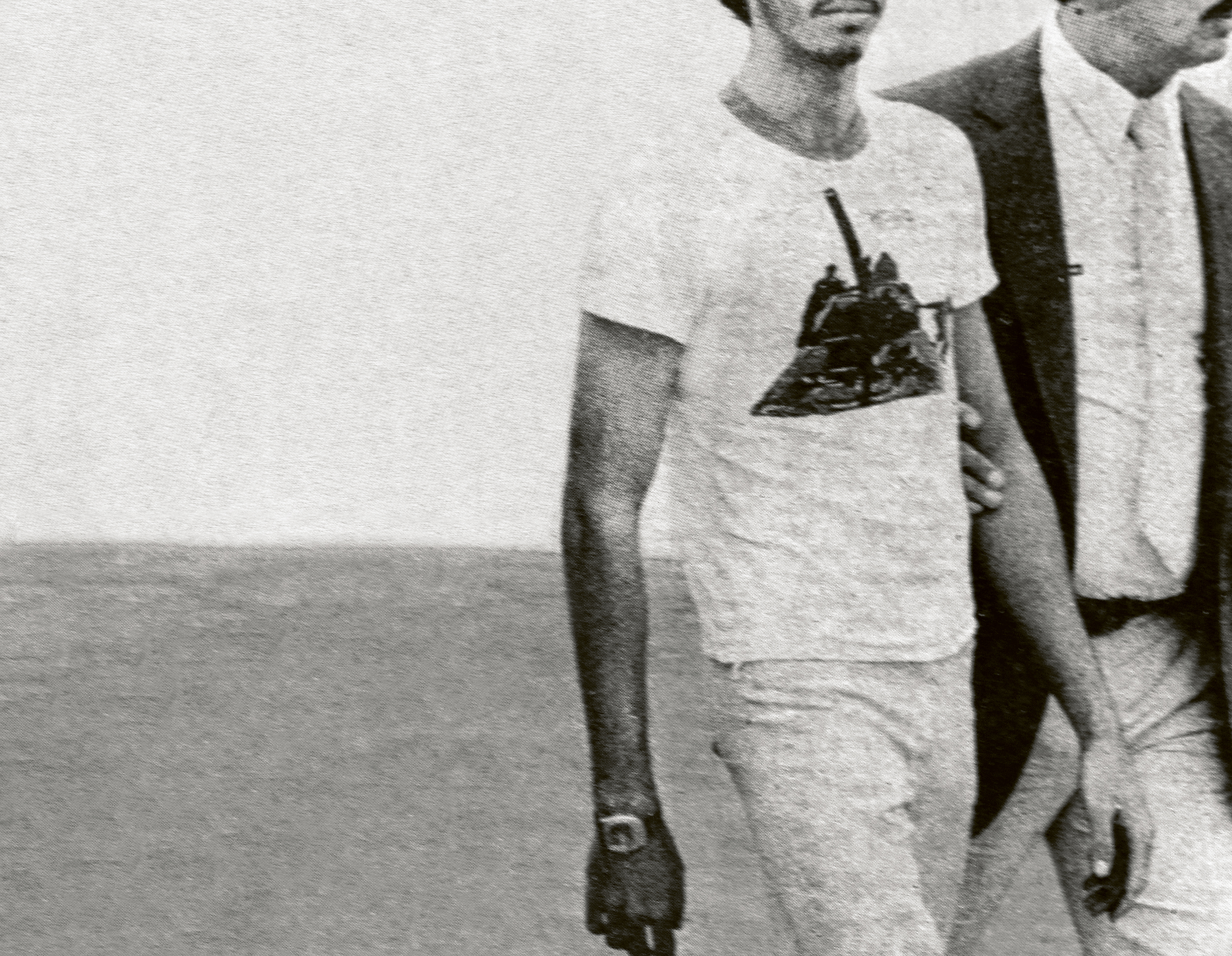

From the series Cargamontón. All images © Rafael Soldi

The Peruvian One to Watch has revisited childhood rituals to examine how intimacy lurks behind violence

Growing up in Lima in the late 1990s, Rafael Soldi’s schoolmates would play a particularly rough game. After singling out a vulnerable peer – often a queer or derided- as-queer boy – the group would wrestle then pile on top of him to the point of partial suffocation. The game is called Cargamontón, a Spanish word which in the Peruvian vernacular means ‘the harassment of one by many’. Years later, a classmate reached out to Soldi to apologise for bullying and targeting him during the game. Soldi, who now lives in Seattle, recalls brushing off the correspondence. He had moved on.

“It was interesting that the bully remembered in a way that was very alive for him, whereas I had built walls around it to build a better life,” Soldi reflects. He came to realise that Cargamontón was a formative incident as he came to terms with his identity. “At times I felt completely humiliated, but as I started to become aware of my own sexuality, I realised that it presented an opportunity for me to experience touch, intimacy and closeness.” This insight has informed two projects over the last five years, which widen to encompass how “violence and aggression have become a foil for intimacy and touch among young men in Latin America”.

“I love images, but I got bored with taking pictures a long time ago”

The first of these works takes the game’s name as its title. Soldi began looking for video footage of Peruvian playgrounds from the early 2000s to reconstruct Cargamontón, “selecting stills that highlight this moment between torture and pleasure”. The series comprises eight large-scale aquatint photogravures, the 19th-century process lending an archival feel to images whose blurred figures resemble assailants caught on patchy CCTV. It is striking that the self-uploaded online videos may have been circulated to further humiliate victims; Soldi engages in a corrective reconstruction, breaking the trauma cycle to propose a new, revelatory understanding. “What fascinates me is how graciously Soldi uses image and language to craft tension between what is visible and what is absent but latent,” says Raquel Villar-Pérez, curator at Impressions Gallery and Soldi’s Ones to Watch nominator.

Soldi went back to Peru – “the scene of the crime” – for the second project, a three-channel film depicting teenage boys playfighting, arm wrestling and marching. Soft Boy extends his gender critique while also reflecting on the influence of religion and the military. Soldi references bell hooks’ re-centring of masculinity in The Will to Change, as well as a Barbara Kruger image from the 1980s which features the slogan ‘You construct intricate rituals which allow you to touch the skin of other men’. In fact, Soldi draws more from feminist art than queer photography in his practice.

The artist’s father was a naval officer who travelled to Antarctica every year and would return with slides to show his family. These images sparked an interest in photography and, although there was no arts programming at Soldi’s Catholic school, he used a makeshift darkroom after school, the space becoming a “magical” retreat from the macho culture outside. “It facilitated an idea of world-building which, as a queer person, became this point of access and difference,” Soldi explains. He then studied for a BFA in photography and curatorial studies at Maryland Institute College of Art before working as an art handler and gallery registrar across New York.

Soldi embarked on a curatorial career at the Photographic Center Northwest, and co-founding the Strange Fire Collective helped him to think beyond photography via publishing weekly artist interviews. “I love images, but I got bored with taking pictures a long time ago,” he explains.

His practice now draws on text, film and installation, while his current research project focuses on the emigration of queer Cubans through the Peruvian embassy in 1980 which led to the Mariel Boatlift, in which 125,000 Cubans fled, many of them fearing persecution under communist leader Fidel Castro. Mientras el cielo gire (As long as the sky whirls) “focuses on how my own country, which continues to be very conservative and homophobic, became a catalyst for queer liberation in Cuba,” he says. It strengthens the link between queerness and migration which underpins all his work. “The experience of migration has a fluidity that speaks to queerness,” Soldi explains. “How do we grieve or how do we deal with mourning the futures we leave behind in the countries that we’re from?”