All images © Pauline Rowan

In Between the Gates, new mother Pauline Rowan navigates an often-obscured side of parenthood

Pauline Rowan was wholly prepared for the realities of motherhood – or so she thought. The 40-year-old had a caring partner, parents who would support her, and a plan for the birth of her child; a natural event during which she aspired to feel at one with the world.

When her daughter arrived in April 2018, everything went smoothly. When the baby was just a few days old, Rowan and her partner moved from Dublin to a new home, an idyllic cottage in the Irish countryside. At the heart of a charming public garden, and just a few minutes drive from her family, it should have been an ideal abode. And yet, exhausted, confused and surrounded by the endless detritus of parenthood, the new mother felt disconnected. “It was the machine of being a mother that I wasn’t prepared for,” Rowan recalls. “I didn’t know when it was going to stop, then I realised that it wasn’t.” In an attempt to take control of the chaos that surrounded her, Rowan began to take photographs. With her daughter often cradled in her arms, she used the only camera she could: her phone.

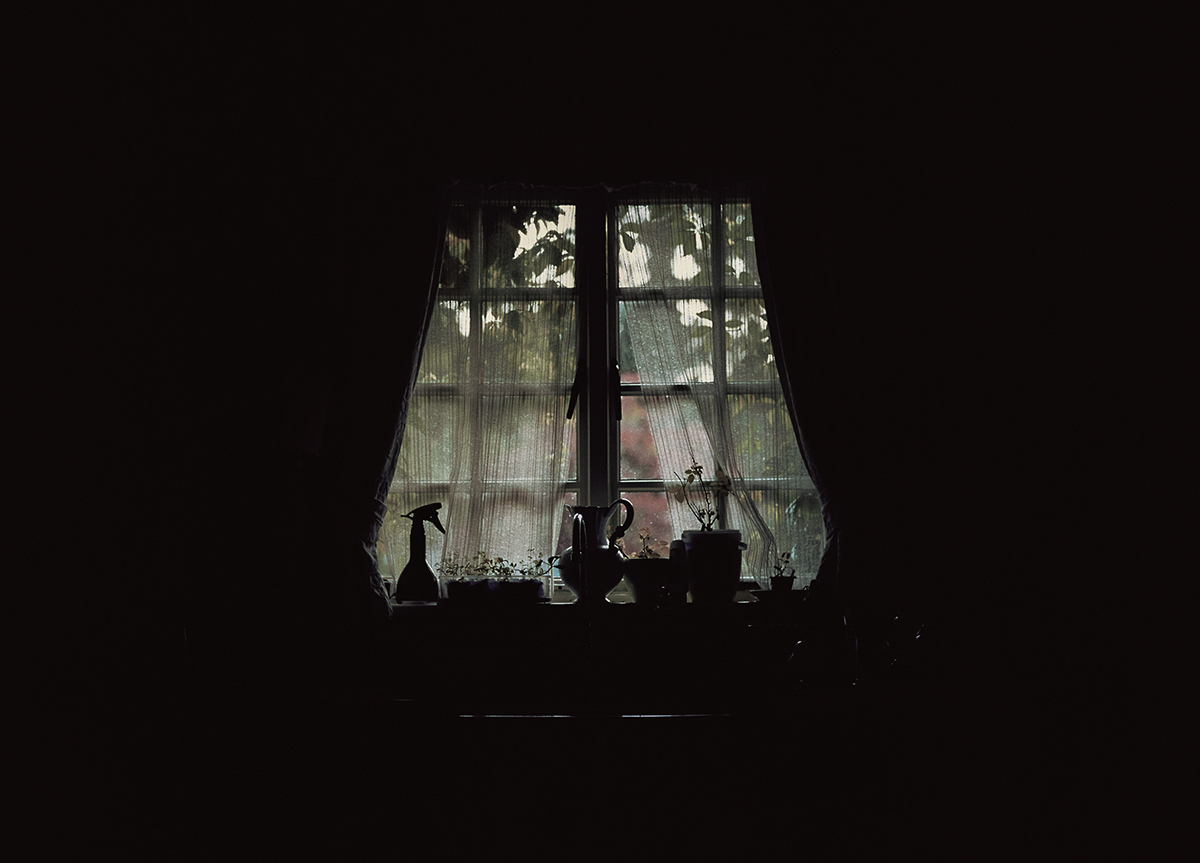

Over the next 18 months she made Between the Gates, and the images in the series speak clearly to her sense of separation and uncertainty during this time. Fragmented and dreamlike, they are, in some ways, unsettling. “I was alone a lot with my daughter,” Rowan remembers. “There’s many dark images of me standing at the back door just looking out into the yard, because when I finally had a bit of time to myself, there was nothing, no one there.”

Rowan’s husband was working long hours, her parents could not visit as often as she had hoped and, just outside her windows, visitors to the public garden surrounding her home peered in. The crowds began to feel like a physical manifestation of her insecurities, seemingly judging her failed attempts to become an ideal mother, wife and woman. “Looking back on the images now, there’s very little editing,” she says. “I knew that if they looked like a contradiction and didn’t quite make sense, then they belonged in the project, and were part of my days or nights of being a mother.

“I suppose it’s a little violent. But I suppose birth is violent too”

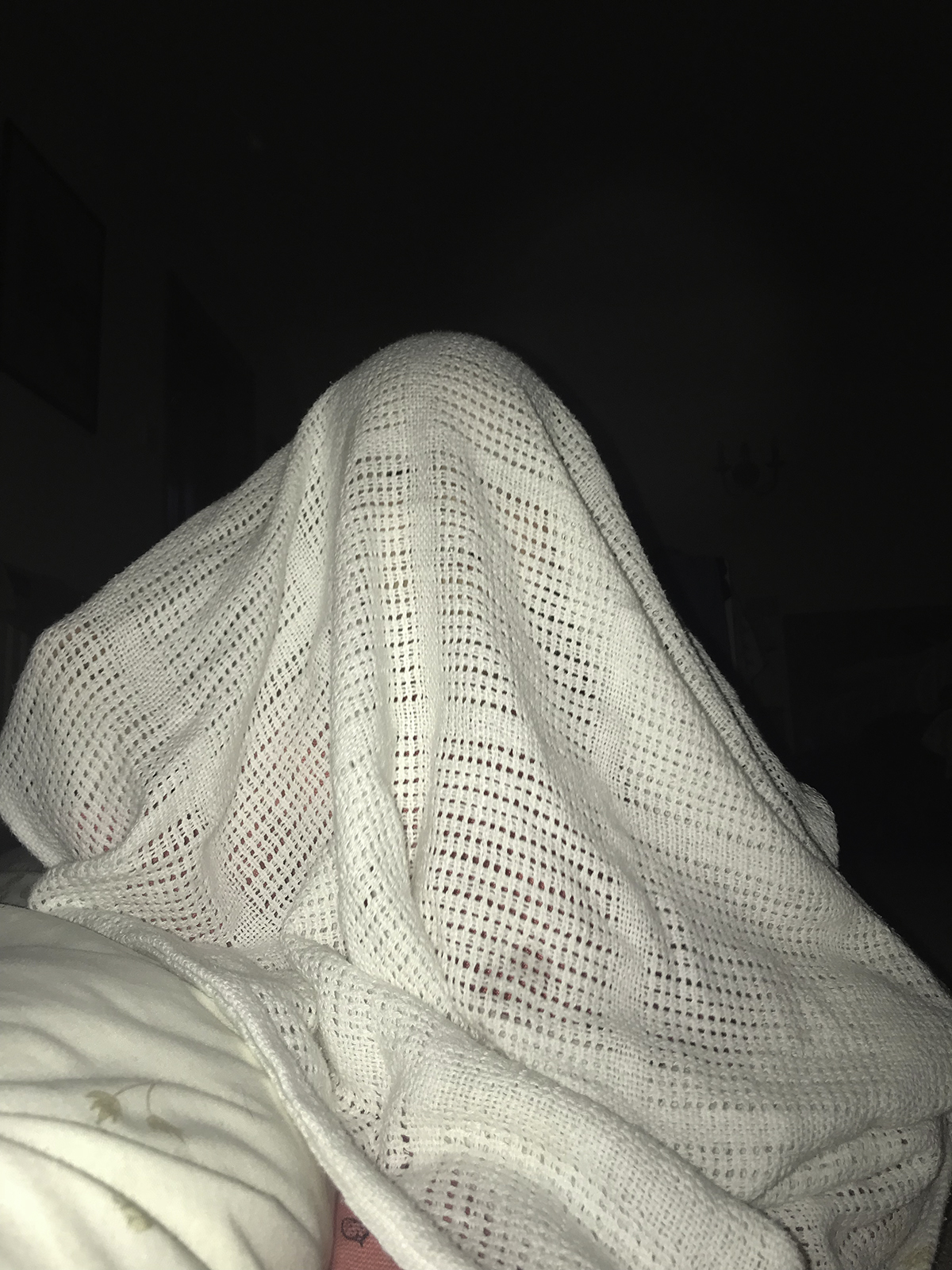

Despite this relaxed approach to editing – mirrored in the many photographs, sometimes presented Polaroid-style, that make up the work – there are shots that stand out to Rowan. A baby’s forearm fashioned from wax, dismembered trees, and weeds forcing their way through cracked pavements represent the boundary between the expected and the achievable. Dead branches hold unclear meaning, while furniture in the midst of being discarded embodies the fragmented elements of a home. Even so, today these images remind Rowan that, through destruction, something new can be made.

Perhaps the most symbolic photographs are those of the magnificent flowers that surrounded Rowan and her partner’s home. During the photographer’s first months as a mother, an ostensibly joyful time, the reality and chaos of which is often obscured, these explosions of life sat uncomfortably alongside broken flowerpots and grass trampled by visiting children. “I suppose it’s a little violent,” she reflects. “But I suppose birth is violent too.”