Matca’s founder Linh Pham and its editor Ha Dao pictured in the organisation’s Hanoi gallery © Nguyên Vũ.

Despite the challenges of scarce resources and strict censorship laws, the two-person team behind Matca – an online journal, community space and publishing imprint in Hanoi – are determined to strengthen their local scene

It is a bright autumn day in London when we meet the pair behind online journal, community space and publishing imprint, Matca. Based in Hanoi, Vietnam, Linh Pham, Matca’s co-founder, and Ha Dao, its editor, are part way through a 10-day networking trip across the UK funded by a grant from the British Council. They have visited Belfast to meet the team behind Source Magazine, and Bristol for the annual Books on Photography (BOP) bookfair. En route, they have amassed 60kg of photobooks, which they plan to haul home in their suitcases. It is difficult to buy these titles in Vietnam due to rocketing shipping costs, they say, but also the country’s strict censorship laws implemented by its communist government. Even online orders can fail to turn up.

This lack of resources – just one of the hurdles prospective artists in Vietnam face – is at the root of Matca’s inception. Pham, who co-founded the organisation in 2016, alongside two other photographers who are no longer part of its day-to-day running, began exploring photography around 10 years ago. “I was looking for educational resources, or some sort of mentor, from which I could learn the craft,” he says. “We have a main government agency that supports photography, but even then it’s kind of like propaganda. We have no infrastructure supporting independent practitioners.” Pham had to navigate his own way into the industry. He travelled to festivals around Asia – such as Cambodia’s Angkor Photo, China’s Pingyao International Photography Festival and Malaysia’s OBSCURA Festival – making connections in neighbouring countries with a more established photography scene.

Eventually he secured work as a photojournalist covering Vietnam and south-east Asia, and has since been commissioned by organisations including Getty Images, The New York Times and National Geographic. Pham built his career out of curiosity and determination, but for the majority of people in Vietnam, the inspiration to do so is difficult to find. “I decided that I needed to create a platform, to provide the information that I wished I could have had in the beginning,” he says.

Matca is the only Vietnamese outlet specialising in contemporary photography. It takes the form of a website due to financial constraints, but also to make it internationally accessible. “From the beginning, it was clear to me that [the journal] had to be bilingual,” says Pham. “There is a lot of great work around but no opportunities to be seen outside of [our] personal bubbles.” Pham recruited photographer and writer Dao to join the team as managing editor and programme coordinator a few months after launch. In Vietnamese, Matca (‘Mă’t Cá’) means ‘Fisheye’: “the ultra wideangle lens so as to capture the bigger picture of Vietnam’s photography scene,” Dao explains. She has commissioned over 200 articles, including interviews with local photographers, and more practically focused pieces, discussing the benefits of enrolling on a residency programme, for example. Matca has built a strong, organic local following and attracted international attention from academics, curators and researchers.

“I think of what we do as mapping – locating photography practices in Vietnam, finding people, featuring their work and interviewing them,” says Dao. “[In Vietnam], personal projects have no outlet. Imagine you are a young, emerging photographer, and you’ve been shooting a project for a while. You look around and you see no opportunity to get further. Publishing a book is expensive; exhibitions are apparently only for very established artists… A photography career is so short-lived here. For us, as a tiny organisation with little resources, featuring these artists online was a way to keep a record of works and ideas that would otherwise be scattered.”

Education is one of Matca’s core pillars. In 2019, the organisation opened a physical space, allowing it to host regular workshops covering subjects such as how to edit a body of work, build a portfolio and write a CV. “People here don’t have access to that, we’re running in a completely different system,” says Pham.

The space functions as a gallery too, although it is officially registered as a coffee shop. According to Pham and Dao, independent organisations in Vietnam cannot legally register as galleries. “It’s a bigger issue with the legal system, because many art spaces in Vietnam aren’t registered – not as a gallery, a non-profit, or even a social enterprise,” Dao explains. This can be problematic when meeting the criteria for international grants. Some institutions will make an exception for Vietnam to ensure that informal organisations can apply.

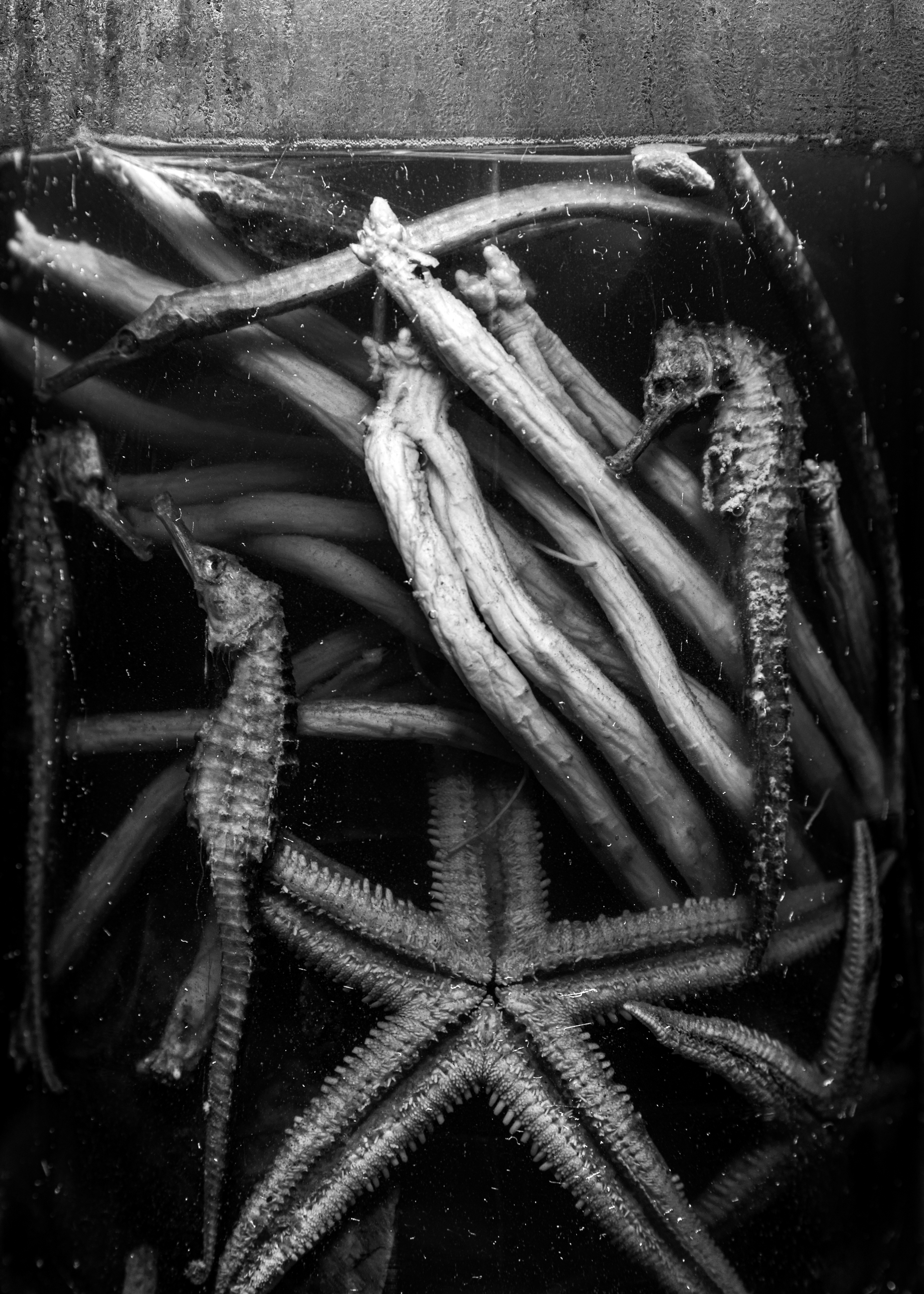

Matca’s publishing imprint, Makét, arrived alongside the gallery as an “extension of our vision,” says Dao. They have published three books to date and are planning more. Their latest publication, Makét 02: From Here On Out, profiles four emerging Vietnamese artists: Binh Dang, Nguyen Duy Tuan, Nguyen Dinh Phong and Thi My Lien Nguyen.

Publishing is a challenging business, but it is made even harder in Vietnam due to censorship laws. In order to produce and freely distribute a book, makers must obtain two types of permit – a printing permit and a distribution permit – which can only be issued by state-owned publishing houses. Some individuals choose to self-print small runs of zines or hand-made books, but this can be a risk. “We have to compromise a lot,” says Pham. “With the publishing house, the printers and the authorities. That’s something we need to keep in mind from the beginning.” For Vietnamese practitioners, acts of self-censorship often happen at the genesis of a project: “We know what’s going to work and what’s not going to work,” says Pham. Even so, the system can still be unpredictable. Binh Dang’s work, for example – which depicts animals suspended in jars of rice wine [above] – was almost censored due to it promoting the consumption of alcohol.

When we speak again in early November, it is a relief to hear that Pham and Dao have successfully rehomed the 60kg of photobooks to Hanoi. These will provide reference material for the organisation’s workshops and Pham’s and Dao’s personal practices. Despite the restrictions, the organisation has already achieved so much, filling the gaps in education and inspiration for future generations of Vietnamese artists. But as detailed in an open letter on its website: “Matca is not just a still image, Matca is a long story that is being told. We hope that you will also accept and believe in what we believe in and join us in the challenging but equally exciting journey ahead.”