In response to the proliferation of disaster imagery following events such as Hurricane Katrina, Hanusik, one of last year’s Decade of Change winners, has spent seven years documenting the landscape and architecture of South Louisiana, showing how much we can learn from it.

“Many climate change stories tend to use the same type of image over and over again to add shock value to the narrative,” begins Virginia Hanusik, speaking about the oversaturation of disaster imagery in the media. “Whether that’s aerial images of flooding, wildfires, or a polar bear in the melting Arctic, these scenes have been synonymous with the climate crisis. But the reality is that every community is currently living with the impacts of climate change at this very moment.”

For Hanusik, this is evident even in her own adopted home of Louisiana, which due to its geographical location, is experiencing coastal retreat, climate migration, and rising sea levels at an accelerated rate. Visually, these effects may pale in comparison to the sheer destruction caused by natural disasters such as Hurricane Katrina. The storm ripped through the state’s city of New Orleans in 2005 and captivated a global audience. Yet photographing these more subtle scenes and studying them is equally as important in our efforts to understand and combat climate change.

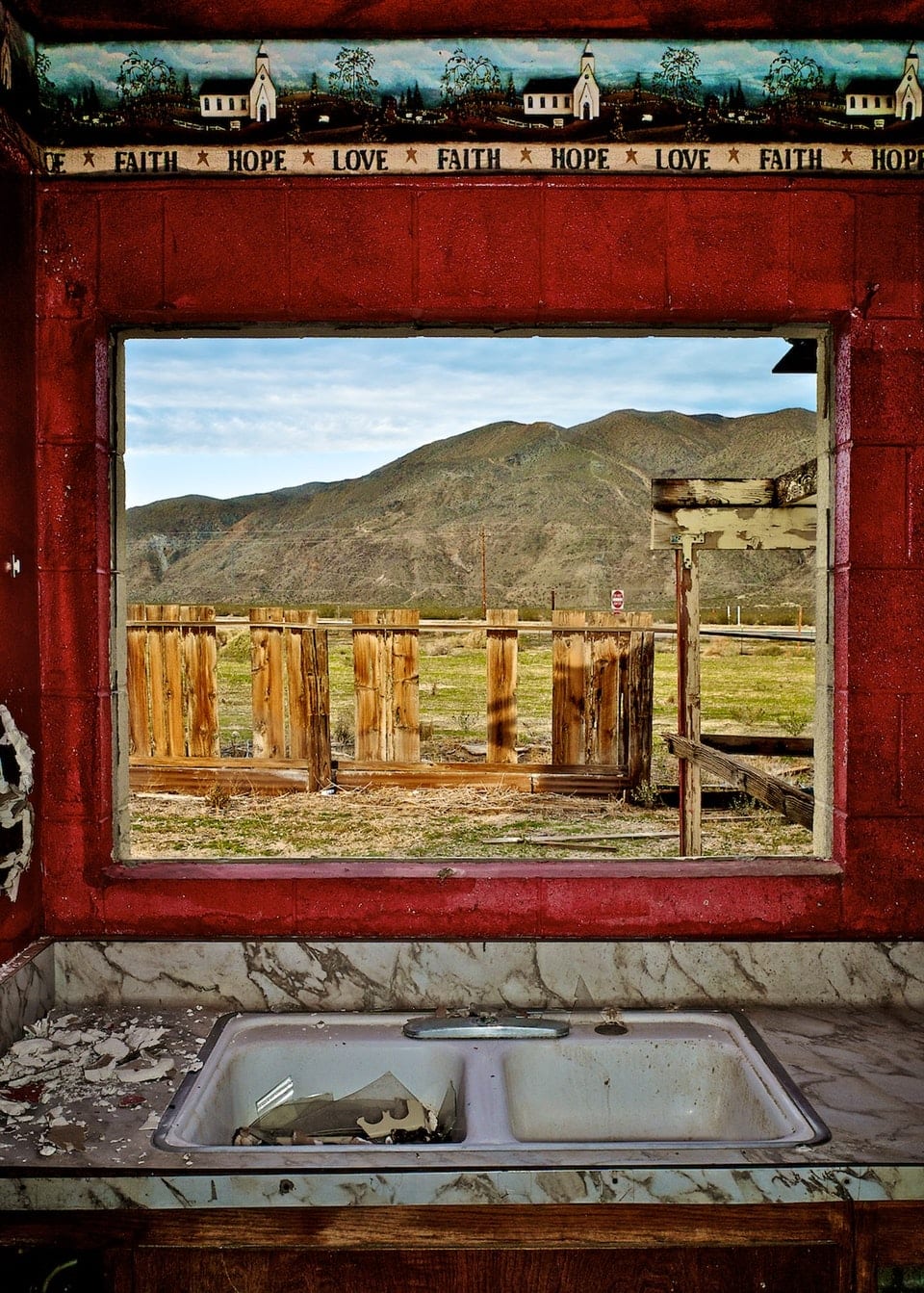

In her recent series All the Good Earth, Hanusik explores how this ongoing crisis is putting unprecedented pressure on Louisiana’s extensive infrastructure. The canals, levees, floodwalls, and drainage pipes that are particularly concentrated in the south of the state are coming up against large amounts of encroaching water, as more land continues to be lost to the sea. These systems, originally built to control the Mississippi river as it forms a labyrinthine delta in the surrounding area, are testament to humanity’s long-held desire to dominate nature. This desire exerts significant influence on the geography of our towns and cities, dictating urban planning and the ways in which we exist within the landscape. As such, Hanusik’s photographic study of this infrastructure looks not only at the present and future effects of climate change on the region, but more widely at our relationship with natural forces throughout history.

“I talk a lot about the role of the fossil fuel industry in destroying Louisiana’s coastline and simultaneously making hurricanes stronger. Disaster imagery may focus on the destruction caused by a storm immediately after it happens, but my approach is to talk more about how the communities of South Louisiana have systematically been exploited by Big Oil and its role in making storm recovery much harder.”

This topic is also the focus of her series A Receding Coast: The Architecture and Infrastructure of South Louisiana, which was created as a direct response to the pervasiveness of disaster imagery in the climate change narrative. In these photographs, Hanusik examines the state’s built environment, proposing it as a symbol of “what we value, how we inhabit space, and the unequal exposure to risk brought on by rising sea levels”.

Even surface-level contemplation of these structures offers interesting, yet unsurprising conclusions. For instance, much of the infrastructure was built by and for the Big Oil companies – the six largest oil and gas companies in the world, also known as supermajors. “I talk a lot about the role of the fossil fuel industry in destroying Louisiana’s coastline and simultaneously making hurricanes stronger,” explains Hanusik. “Disaster imagery may focus on the destruction caused by a storm immediately after it happens, but my approach is to talk more about how the communities of South Louisiana have systematically been exploited by Big Oil and its role in making storm recovery much harder.”

This exploitation extends to the infrastructure itself, which serves to protect only certain parts of the population. A floodwall, for instance, acts as a barrier to disaster for some, and as a reminder of potentially unavoidable danger for others. These politics of space, which play out in myriad ways throughout Louisiana’s heavily-engineered landscape, provide crucial insights into how we have historically dealt with nature’s challenges, and how we might do so in our uncertain future. Though we have no control over where a hurricane hits, we can influence which sections of land become “sacrifice zones” as sea levels rise. The areas we designate to be swallowed up say a lot about what – and more importantly who – we value.