Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

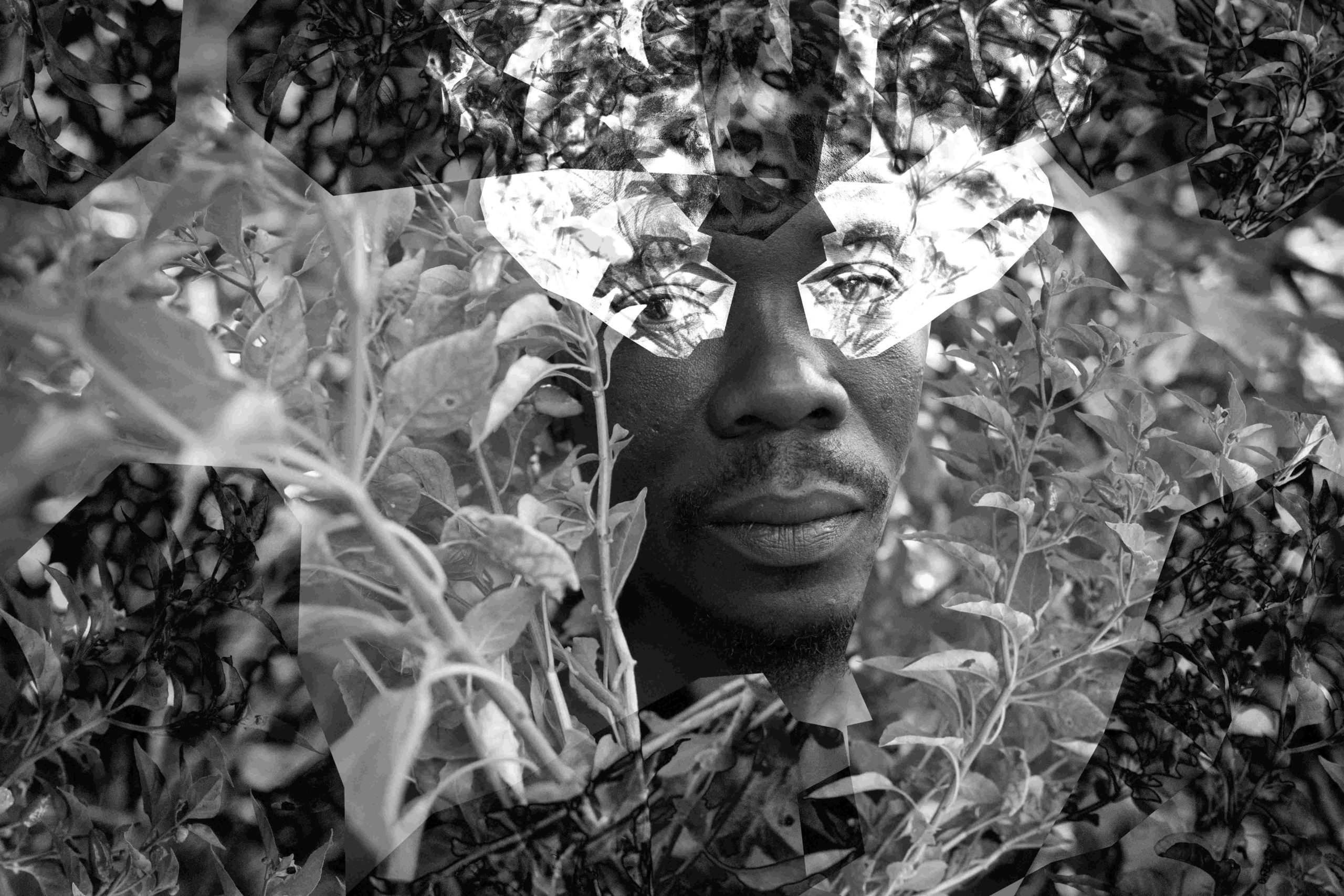

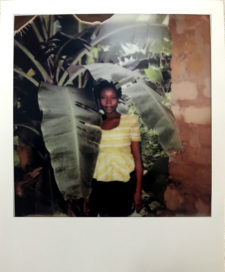

Chernoh Sesay is pictured with his pepper plants. He is a farmer who plants rice and pepper, which he then sells to traders who visit the community. The water source he uses for drinking water is far away and dirty. Chernoh is married with five kids and is the main breadwinner. Sometimes he goes to fetch water for children to bathe in, or the children have to go to school without washing. Chernoh says politicians have come to the area to campaign about [the lack of clean water], but they have never helped. © Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Chernoh Sesay is pictured with his pepper plants. He is a farmer who plants rice and pepper, which he then sells to traders who visit the community. The water source he uses for drinking water is far away and dirty. Chernoh is married with five kids and is the main breadwinner. Sometimes he goes to fetch water for children to bathe in, or the children have to go to school without washing. Chernoh says politicians have come to the area to campaign about [the lack of clean water], but they have never helped. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

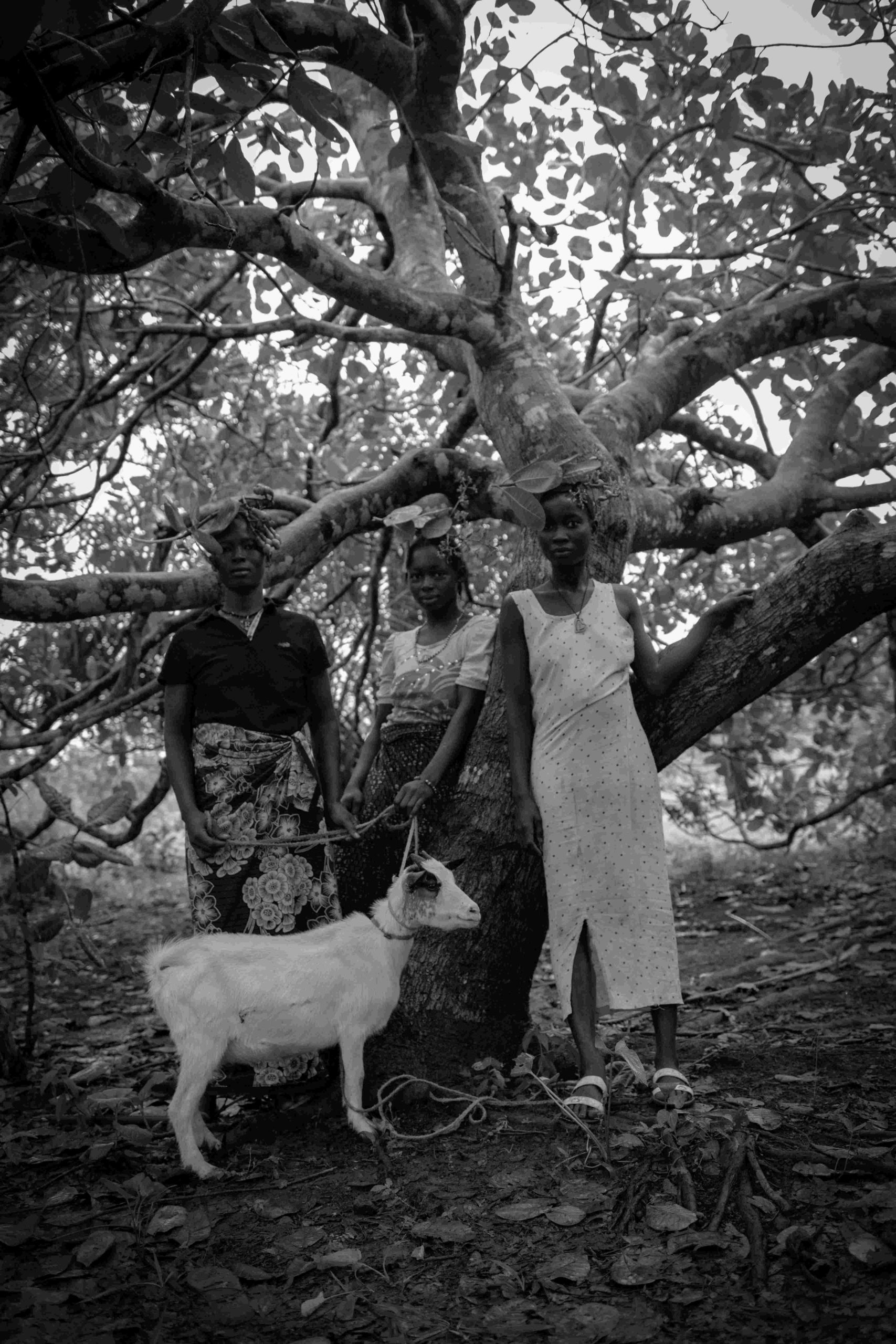

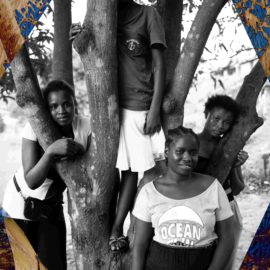

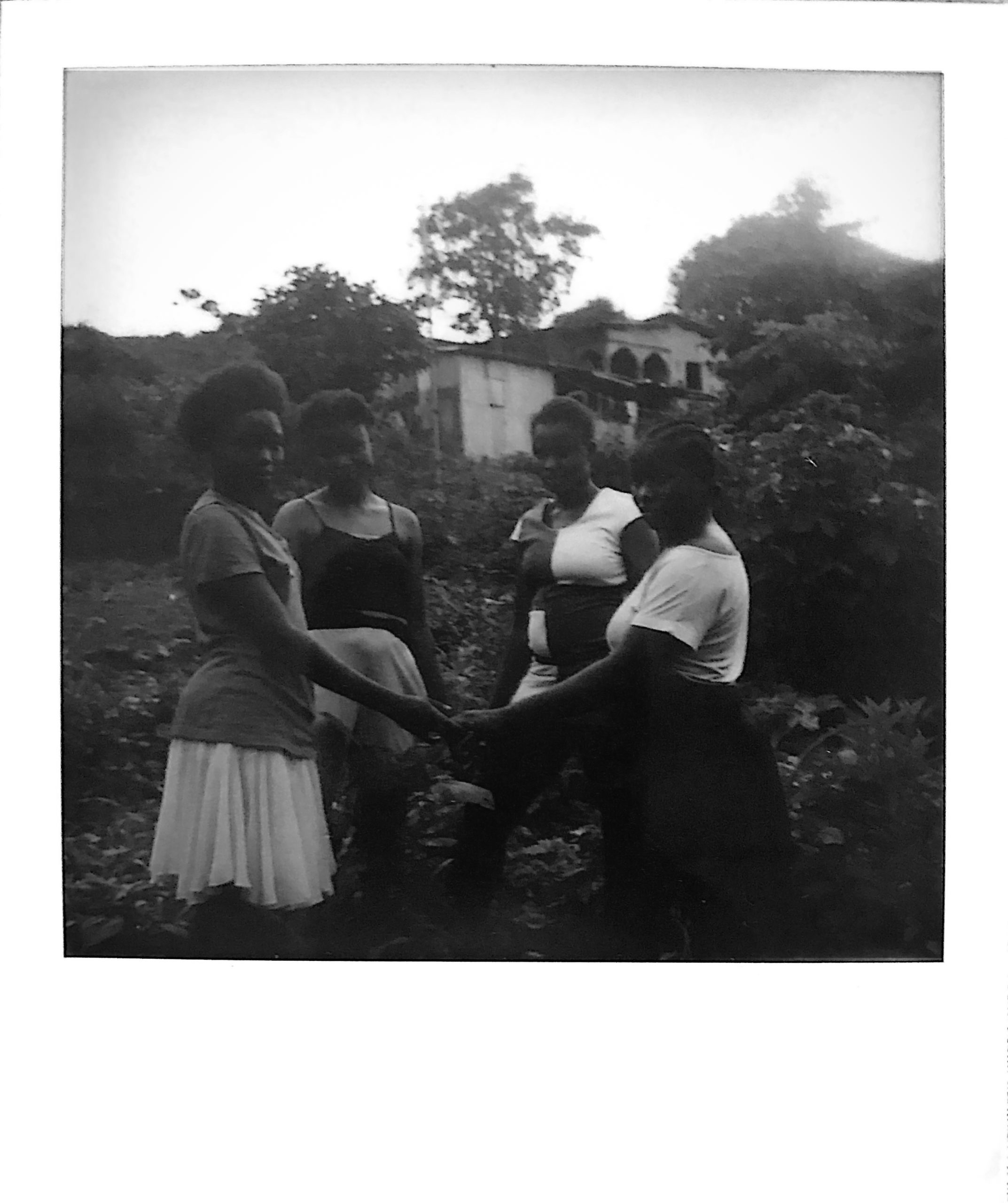

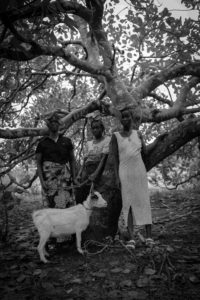

Kadiatou H. Kamarra (far left) has been living in this community for 10 years. As a farmer, she mostly farms rice and cashew nuts. Maa Kanu (centre) farms pepper, cucumber and cassava. She relies on rain in order to water her farm. Mariatu Kanu (far right) plants pepper and okra with her husband. The money they make from farming is used to buy food for her family. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

The Tombotima community relies on cattle rearing and farming vegetables and cashew nuts. They have no well and have to travel long distances to get water that isn’t clean. The men are responsible for collecting water, as it is considered too dangerous for women, especially when they are pregnant. The community has noticed that rainfall is not as frequent, or fast, as it used to be, which affects their ability to farm. (Left to right) Kadiatou H. Kamarra, Maa Kanu, and Mariatu Kanu stand under the community’s cashew nut tree, wearing cashew nut branches on their heads. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

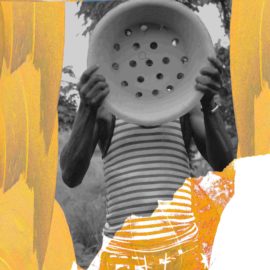

Memounatou Kanoh, 18, lives in the Mabettor community and poses with a clay pot she made. She has lost both her parents, but learned the practice of pot-making from them before they died. Memounatou has a child whose father is currently in prison, making her his sole parent; the money she gets from work is used to feed and clothe her child. Memounatou has little support, relying on small gestures such as male members of the community who help to carry the clay she uses to craft her wares.© Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

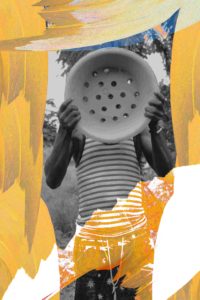

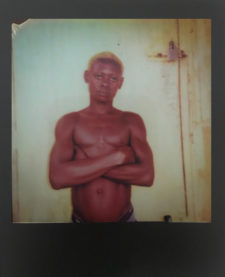

Mohamed Sankoh holds a clay pot he has made. He learned how to make pots from his father every day after school with his brother, Abuji. Mohamed speaks about how rising temperatures are affecting water levels, especially in dry seasons. Both brothers work in order to send their younger brother, Ousman, to school. They want him to carry on his studies and go further than they were able to. They also send money to their sister who is away at school. © Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

(Left to right) co-workers Ibrahim B Conteh, and brothers Abuji and Mohamed Sankoh, pose with their products in the swamp that provides water for making clay goods. Ibrahim was taught how to be a pot-maker by this mother 17 years ago. Though he did not finish school himself, the money he earns goes towards his child’s studies. Ibrahim says that they need water in order to make products with clay. © Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Abuji Sankoh makes his livelihood as a potter. He used to go to school, but started work under the mentorship of his father. After his father’s death, he continued working with pottery and has become the father figure within the community. His older brother, wife and mother help sell the wares they make in order to live and survive. © Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

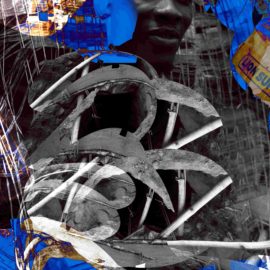

Clay pots lie on a factory floor used by the Mabettor community. Only 250 people are a part of this community, which mostly survives on the production of clay pots and other homewares, such as candlesticks and vases. The factory was set up by a German organisation many years ago, and the community continues to use the space. Water used to make the pots is sourced from a nearby swamp, which often dries up during the dry season - halting the production of their wares. When this happens, the community borrows or buys water for 1000 leones per container from nearby villages with better water supplies. Though there is a well in the community, they lack the tools needed to dig further for access to more water. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

(Left to right) Makenen Lahi, Adama Joe, Mme Musu Jaward and Sata Kanneh are elders within the community and pose in front of the farming garden where they grow okra. They are wearing a mixture of cocoa, banana and palm leaves to symbolise the most important farming assets to their community. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Mme Bindu Kamara is an elder in the Taninawahun community and is part of the water management community. She is wearing palm leaves on her head and a cocoa leaf on her mouth. Members of the community created masks out of leaves, a reflection of life during the pandemic. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Moina Jaward (left) and Islai Kamara live in Taninawahun where they attend high school. Their hats, made of cocoa leaves, celebrate the community’s most important export: cocoa. Their glasses are made of palm leaves. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Taninawahun is a community that received WASH service from Wateraid between 1987 to 1989. Wateraid provided them with a gravitational water system which the community continues to use today. Since it was implemented, however, the community population has increased. Wateraid plans to upgrade the water system so it can serve the growing community. Hawa came to our shoot day wearing palm tree leaves, one of the vital crops that requires water to grow, as the Taninawahun community sell palm oil to sustain themselves. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Taninawahun is a community that received WASH service from Wateraid between 1987 to 1989. Wateraid provided them with a gravitational water system which the community continues to use today. Since it was implemented, however, the community population has increased. Wateraid plans to upgrade the water system so it can serve the growing community. Hawa came to our shoot day wearing palm tree leaves, one of the vital crops that requires water to grow, as the Taninawahun community sell palm oil to sustain themselves. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Taninawahun is a community that received WASH service from Wateraid between 1987 to 1989. Wateraid provided them with a gravitational water system which the community continues to use today. Since it was implemented, however, the community population has increased. Wateraid plans to upgrade the water system so it can serve the growing community. Hawa came to our shoot day wearing palm tree leaves, one of the vital crops that requires water to grow, as the Taninawahun community sell palm oil to sustain themselves. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Joseph Thulla, 64, was staying in hospital in Ja Kingdom when the mudslide occurred. It completely wiped out his one-bedroom house, killing 10 family members, including five of his children. Almost all of Joseph’s neighbours were killed after their homes were destroyed; he can name 43 people that he knew. This is a portrait of him with the ruins of one of his closest neighbours, Pa Unisa, who was also lost that night. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Mariama Kai, a 36-year-old teacher living in Ja Kingdom, recounts how a mudslide that killed many members of the community began on 14 August 2017. She recalls how the force of the flooding from the continuous heavy rainfall kept pushing bodies further into the village. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

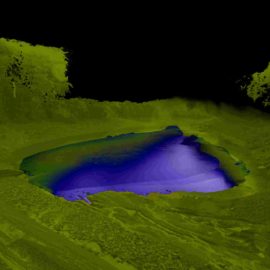

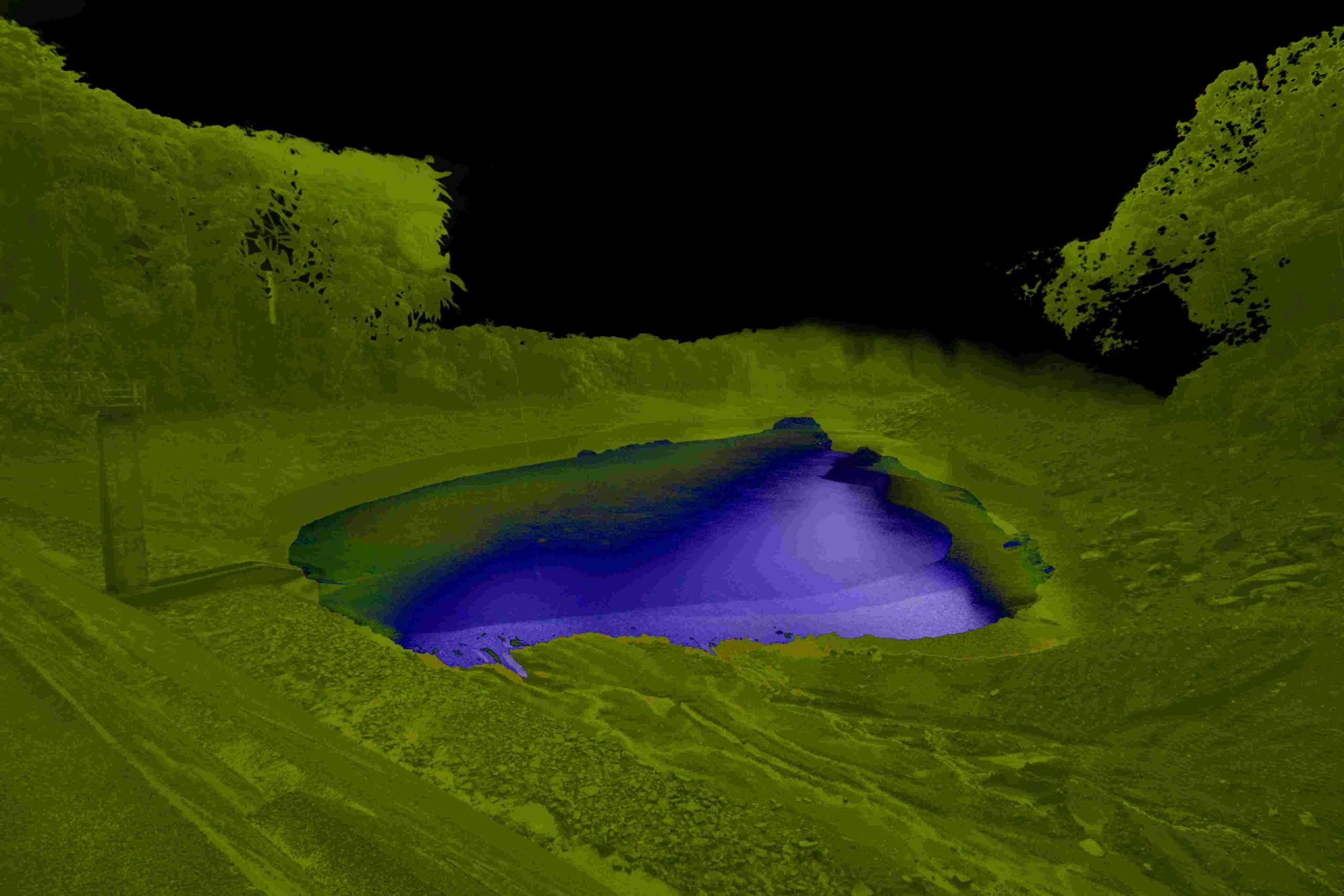

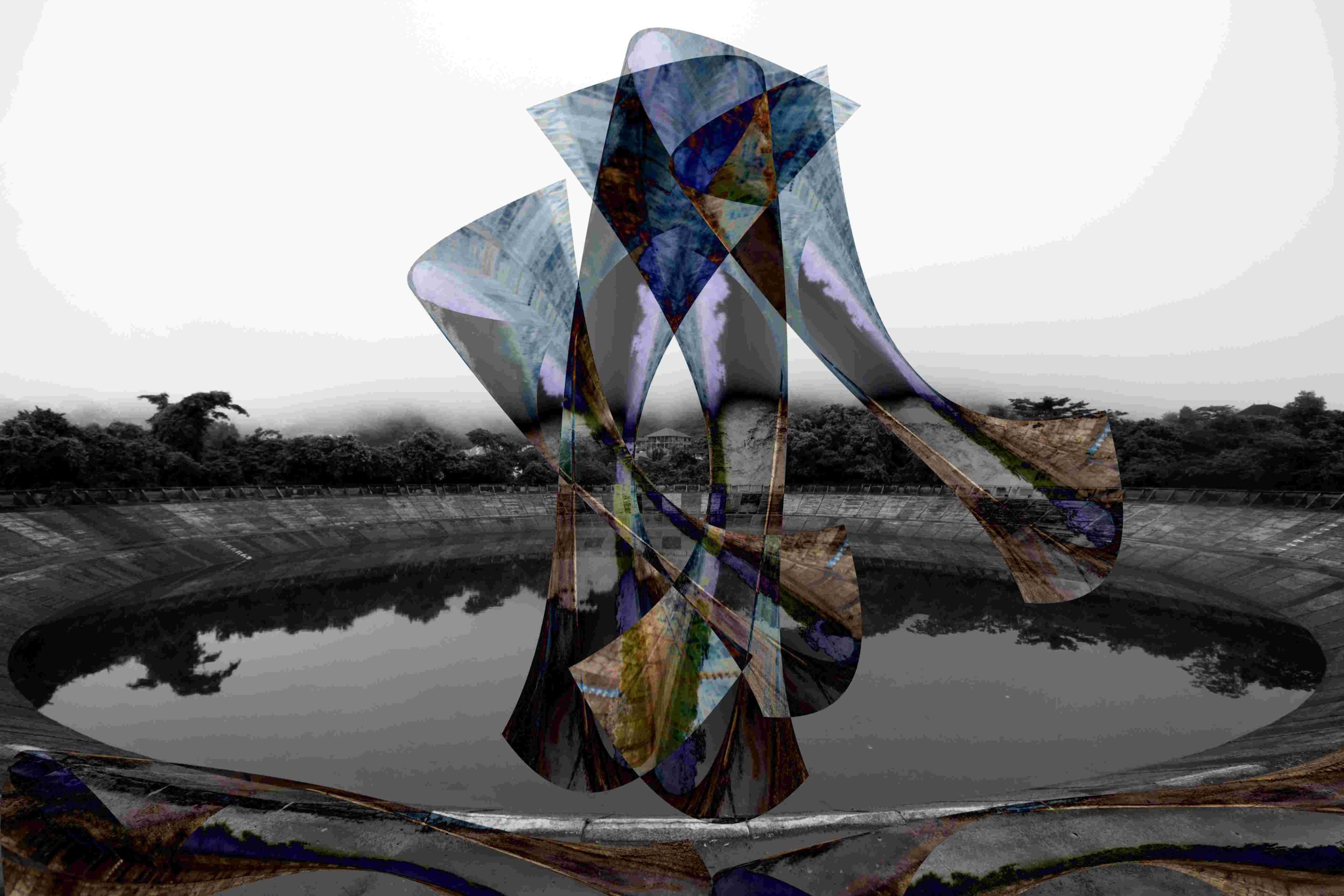

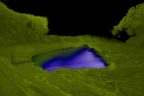

The Congo Dam is one of the two main dams supplying water in Freetown. It shares a stream with the Guma Dam, where the water supply has been affected by deforestation in the area. Here, the Guma Dam is photographed in early July, more than three-quarters below its expected capacity for the time of year.©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

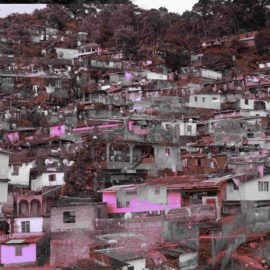

The Guma Dam to the west of Freetown is one of two main dams that supply water to the capital city. This photograph from early July shows it less than a quarter full. By this time of year, the dam should be full. Changing weather patterns mean the rainy season that would usually start between May and June now begins in July, and lasts until October. From December to March, the water in the dam dwindles until the next rainy season. The city’s population of 1.5 million people needs around 35 million gallons of water a day, but the company that supplies water only has the capacity to pump 23 million gallons. 4 million gallons of that water services the east of the city, where most of the population lives. The water system is outdated and ill-suited to the dense overpopulation of the city, built in the 60s for around 100,000 people. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

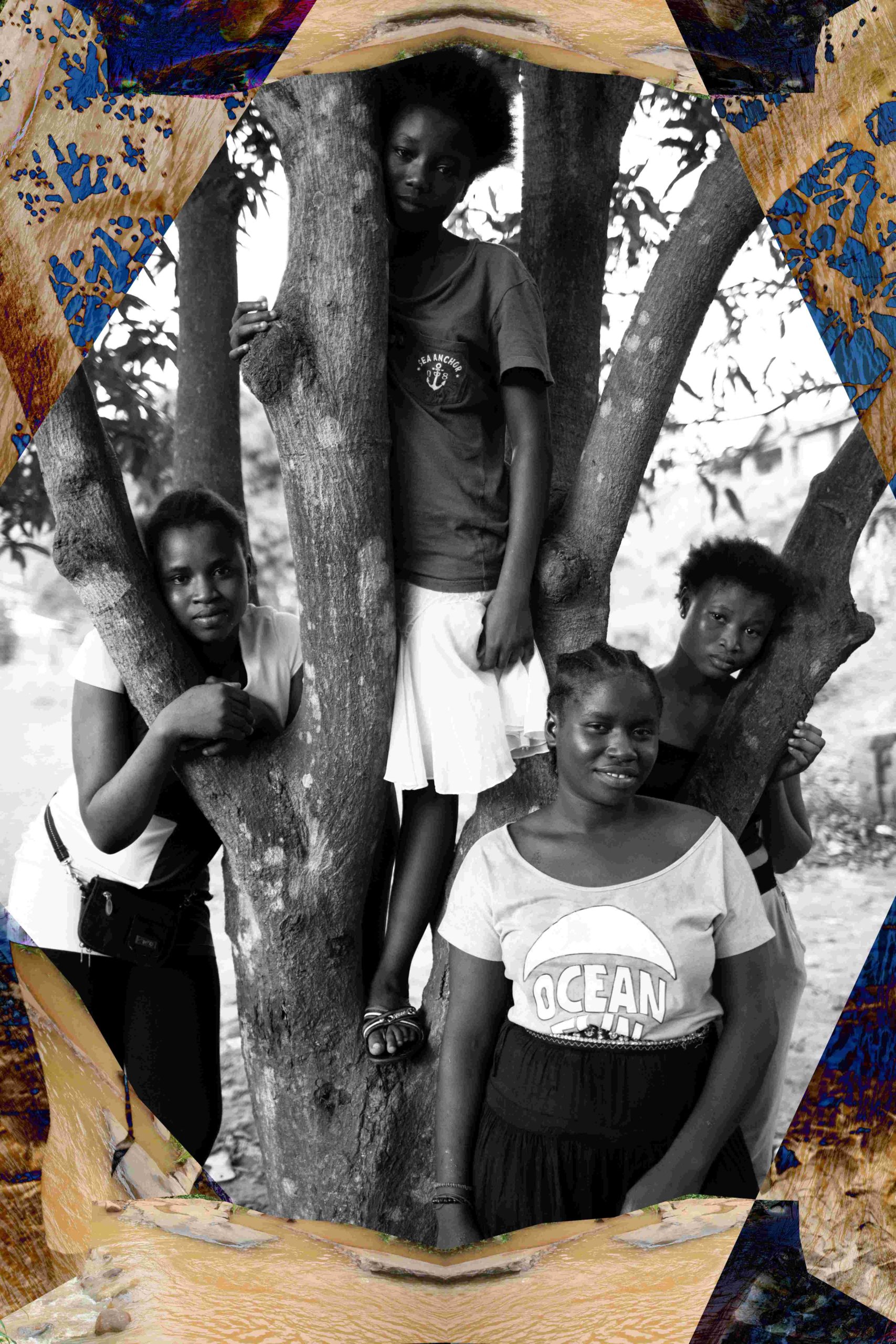

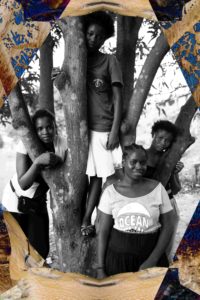

(Left to right) Sisters Salimatou, 17, Kadijah Sankoh, 18, Rebecca Smith, 20, and Gladys, 16, near their home in Ja Kingdom. They can no longer drink from what remains of the neighbourhood stream, now polluted by dirt and bodies from the mudslide. To this day, they continue to find bone fragments in it, and it still carries a smell. The water source the sisters use for drinking comes from someone connecting cut pipes together, but they are not sure where this source of water comes from. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Sisters Kadijah Sankoh, 18, and Gladys, 16, pose together in Ja Kingdom. They were there on the night of the mudslide and recall how many body parts were found. A baby was miraculously found alive, saved from suffocating because his fingers were up his nose. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

A portrait of Fanta Sesay near the waterfront where the women attempt to collect water. The women are sometimes forced to use seawater because of dwindling supplies from the public pump. Mabinti says, “water is life” and they need it for everything from cooking to washing their children’s clothes when they return from school. The price of water has increased from 2500 leones to 3000 leones. It now costs as much as 5000 leones, with an extra 4000 leones to cover transportation. The women worry about how they will manage with the upcoming dry season. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

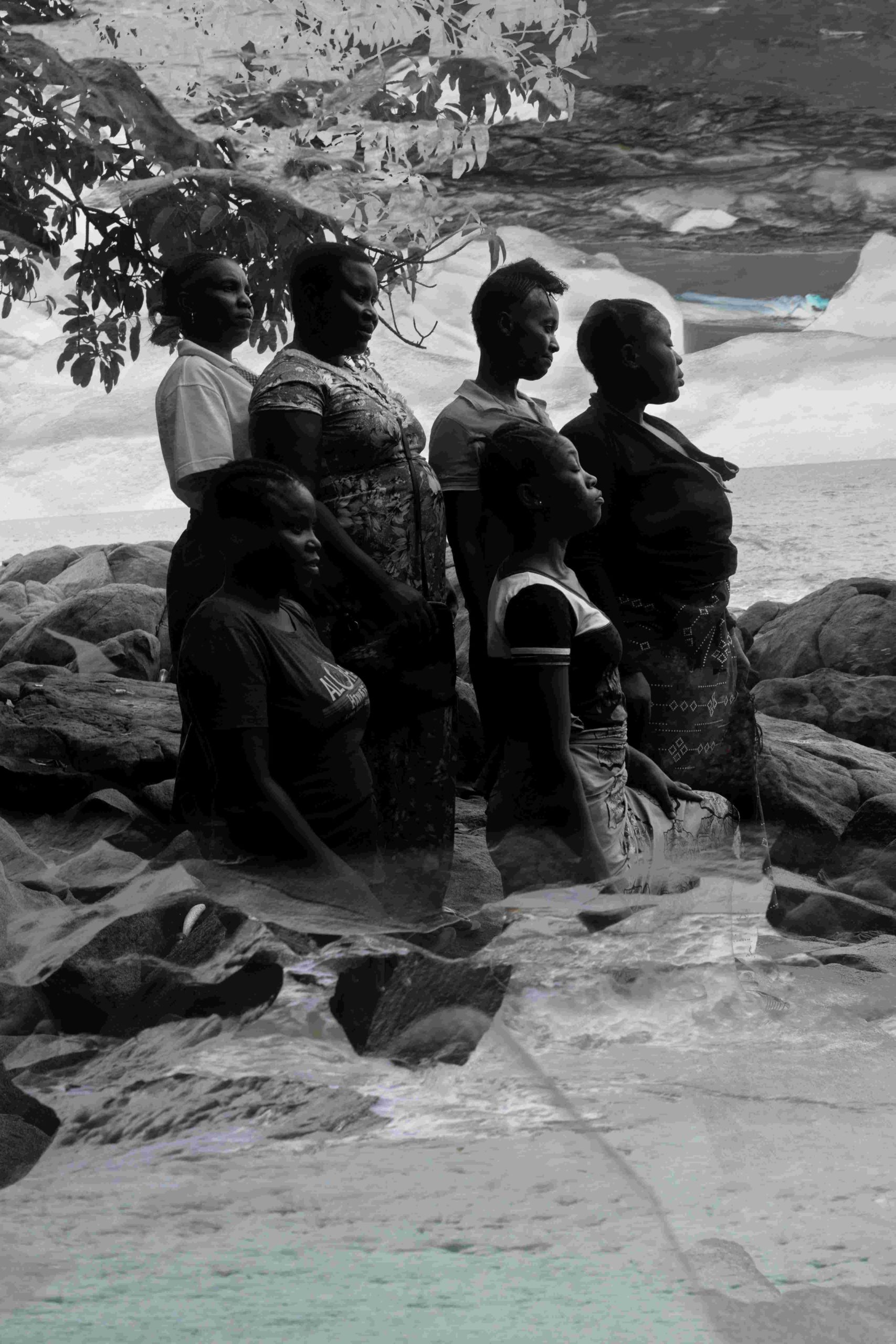

(Top left to right) Rugiatu Davies, Fanta Sesay, Josephine Sandufou, Mariatou Mundah, (bottom left to right) Mabinti Kamara and Teneh Kidjah pose near the old police station on Police Beach, which is now inhabited by members of the local community. The women use a public pump in the area to collect water. According to Mabinti, they used to collect water twice a week, but since March 2021 the pump is rarely open. They have tried to contact the Guma Valley Water Company, who supply water to the capital, but the source of the problem has still not been identified. Instead, they collect rainwater during the rainy season, and occasionally they are able to access water from private wells owned by members of the community. Thieves are common in the area, however, so those who own private wells often limit access to others. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

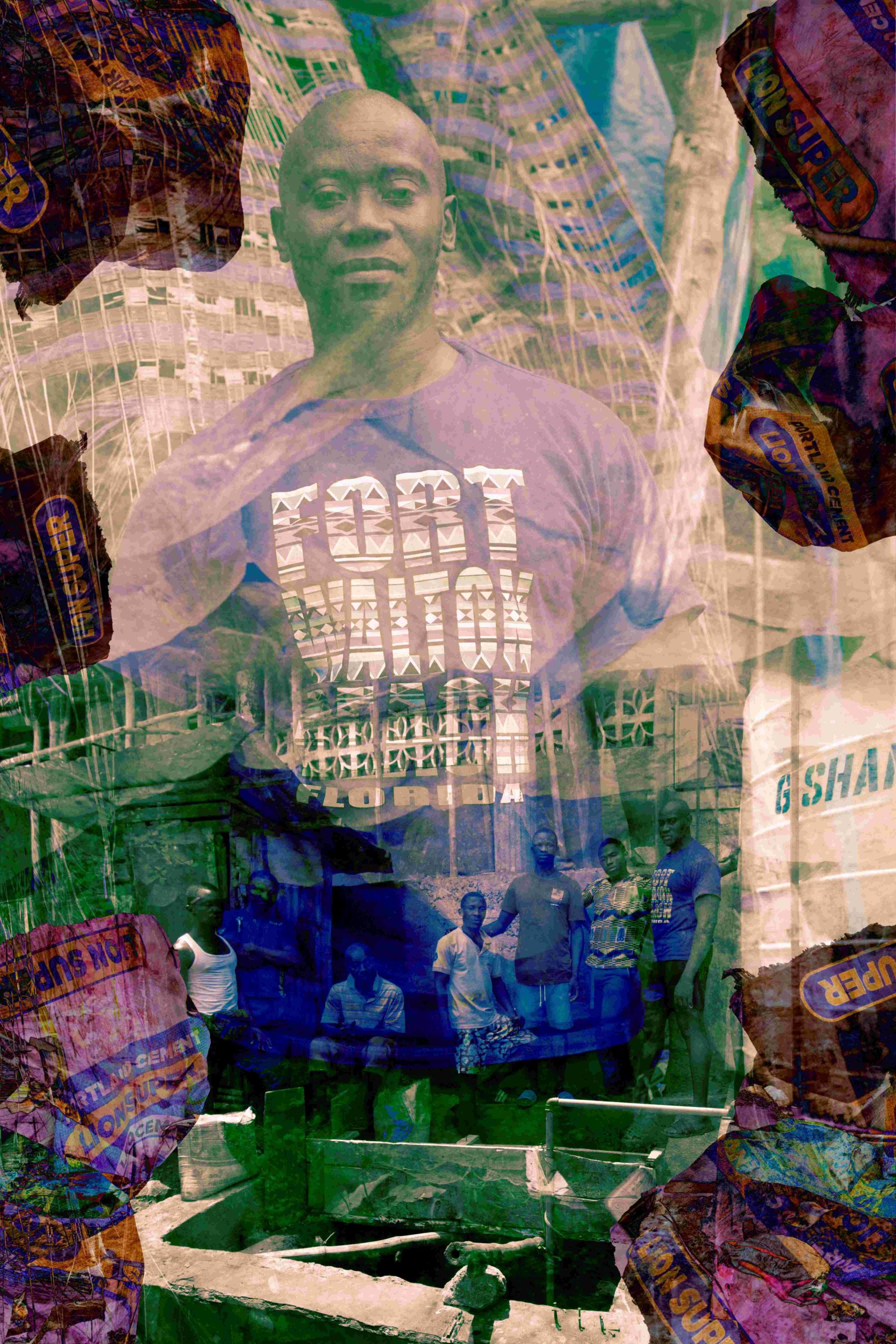

The four men on the right of the image, (left to right) Amarra Samura, David Moingeh, Aioh Mbayoh and Alimamy Nehemiah Kargbo spent almost six months digging a 30-foot well for the Dwarzack community. When we met them, they were testing the well’s efficiency - noting the intervals at which the connected 5000-litre water container to fill up. Other community members stand to their left for support. Alimamy Nehemiah Kargbo is chairman of the Dwarzack Police Partnership Board. His father was the chief of Dwarzack for 30 years and helped install a water tap, local roads and electricity supplies for the community. Alimamy hopes to continue his father’s legacy and got together with the other three men to dig the well. The YMCA provided 5 million leones to help build the well, with which they were able to dig and concrete it. The machine that pumps the water from the well was bought with the men’s own funds, and they hope to buy another 10,000 litre container to continue their work and supply water to the community. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

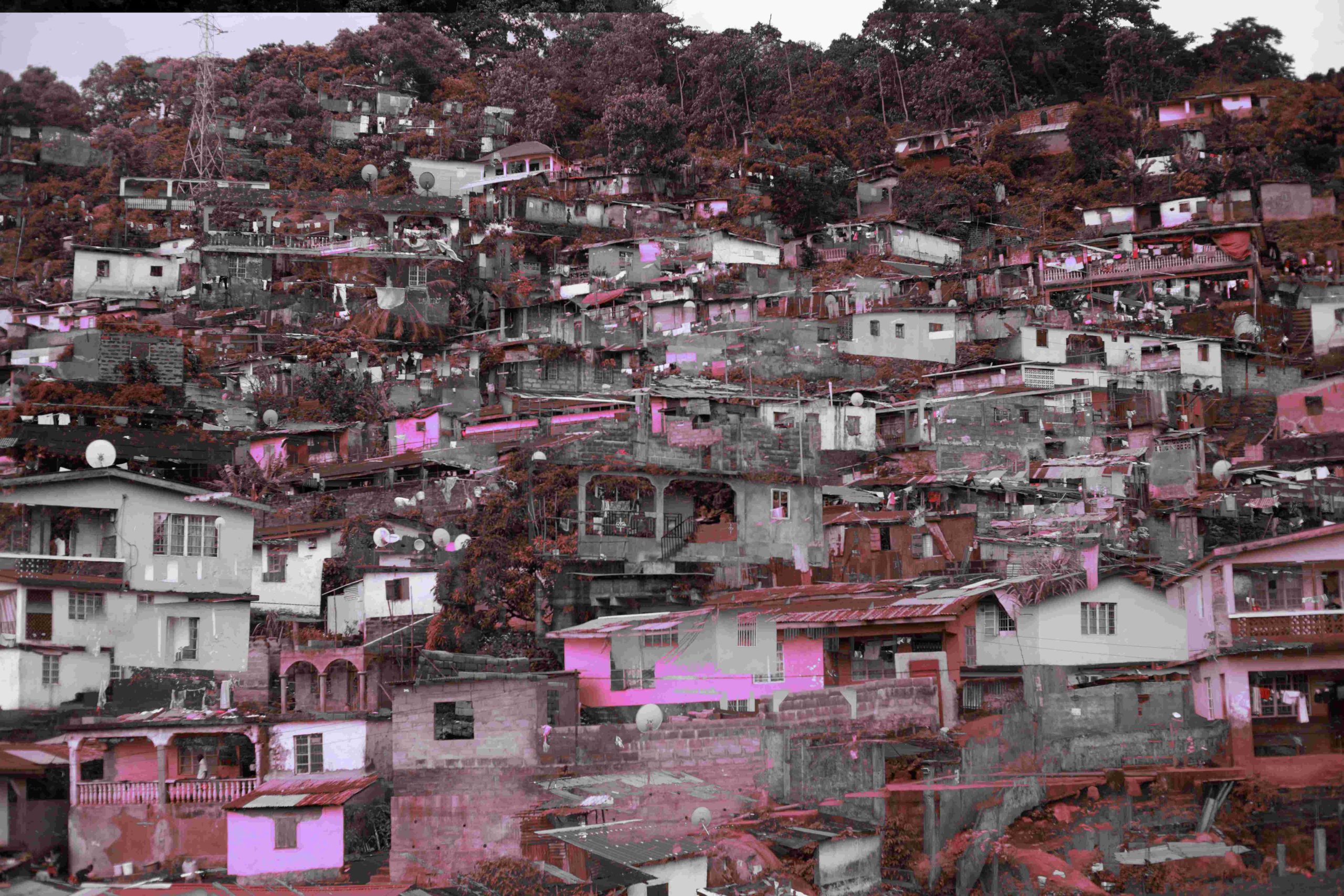

Though Kroo Bay is an informal housing settlement, the community have found ways to organise and use the waste and debris that washes up on the shores, constructing barriers for areas that easily flood. They also use some of the waste to map out the foundations for new allotments for new residents to build their corrugated iron house on.©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Abdulrahman Kargbo, 15, collects water from a nearby pump five times a week, taking turns to carry six 5-litre water containers a day. Each rubber container costs 1000 leones. He is a dancer who joined a dance group two years ago that has since won four competitions. During the rainy season, however, the group are unable to make money from dancing as heavy rainfall halts their activities. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Healthcare workers in Kroo Bay report high rates of child malnutrition, caused by poverty, and accentuated by rising global food prices. Corrugated iron sheets are used to make houses in the community, known as Pan Bodies, which create a seemingly endless labyrinth of metal. The multiple textures used here capture the essence of this©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

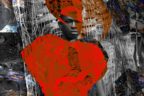

Kroo Bay is an informal housing settlement on the coastline of central Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone. In 2009, it had an estimated population of 10,989 people. Residents of Kroo Bay lack adequate access to sanitation and health services. Despite this, the community is thriving and the residents of Kroo Bay cherish the community that they consider as their home. Kadiatou Kamarra, 25, a resident of Kroo Bay for eight years, stands for a portrait by her home. The textures used for the collage come from the polluted sea water that surrounds the community which, during the rainy season, floods parts of Kroo Bay.©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

A portrait of Pewama community member Fatmata Koroma, who brought her fishing net on the day of our shoot. Each community member was keen to share the skills that contribute to the prosperity and wellbeing of Pewama. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Sahr Kabba, 38, and his daughter Kumba Kabba, six, live in Freetown’s East End. Sahr is in charge of the maintenance of a public community water well near The Approved School. In order for the well water to remain clean enough for use, he has to buy a sterilising product which dissolves into the water. The sterilising products are now hard to find as they are in high demand. The well has been used since 1997, but as the population increases, it is in constant use and needs regular maintenance. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

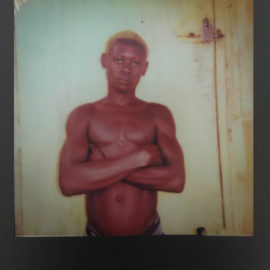

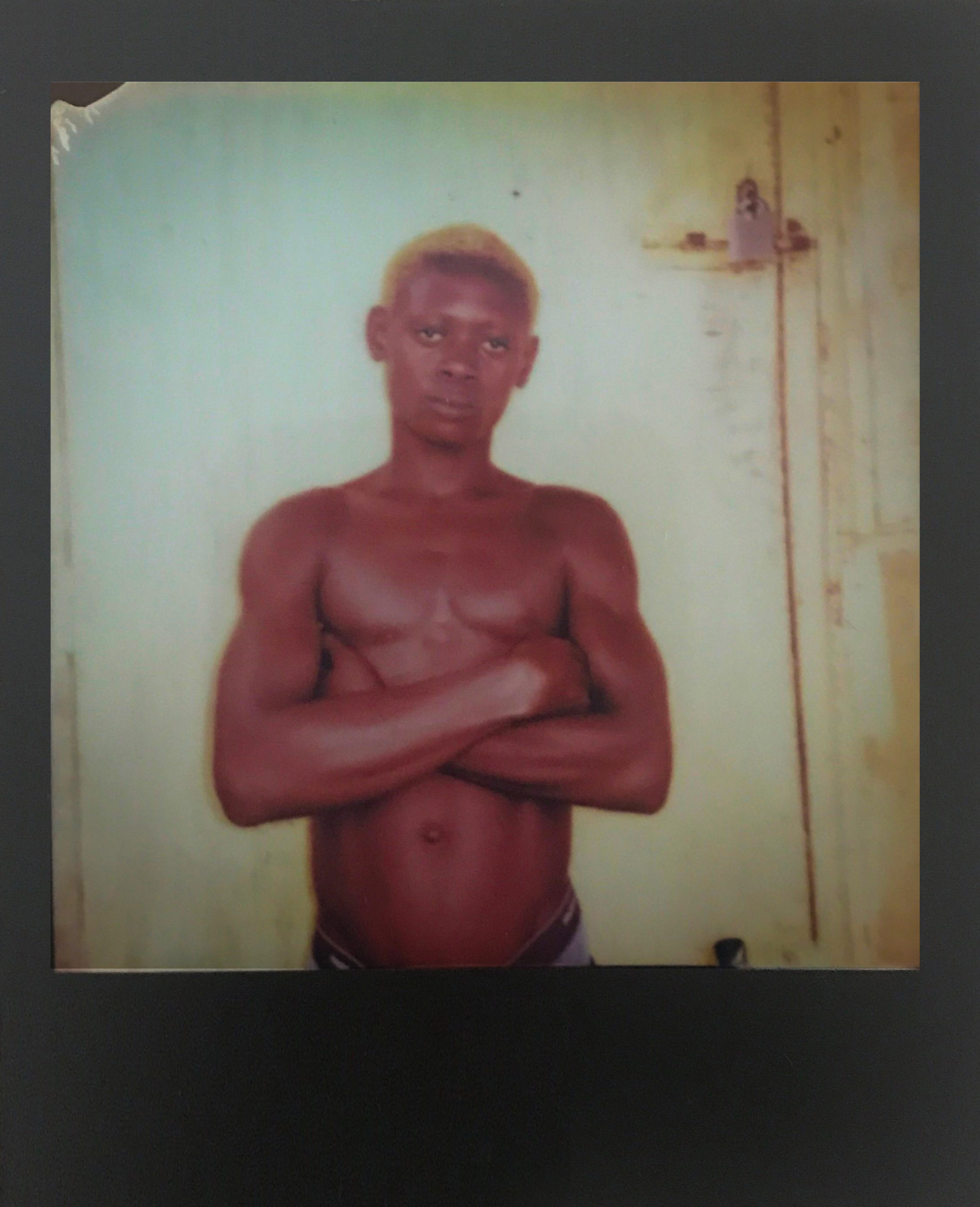

Abubakarr Kamara, 19, is a carpenter who buys water to wash cars in a wayside garage with his brother. It’s the most reliable way for him to make a living. The East End ward of Freetown is heavily populated and receives less water than the western part of the city. As the cost of water rises, work like Abubakarr’s will become increasingly difficult. Children from the hilly areas of Freetown, where water supplies do not reach, travel and sleep near by the garage in order to be first in line to collect water in the morning. As a result, many of them are unable to attend school, and unexpected pregnancies sometimes occur as a result. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Mme Amie Murray, from Konima community in Bo District, carries wood that will be burned into charcoal. The shortage of water in the area has led the Konima community to rely on charcoal production as a main source of income. They also produce and sell bags, baskets and furniture, but the wicker and bamboo they use has to be soaked in water. The community currently has no functioning well, so they have to travel to collect water. During the dry season, they have to travel further as natural water sources, like streams, are increasingly scarce as temperatures rise. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Fatti Mattia shows off a pineapple, something that she regularly farms. Fatti expressed how much the Wateraid well changed the lives of the Pewama community. Before, they had to walk long distances to fetch water from a dirty swap. Now, the community well is only a few steps away, from which she can collect water for her family and crops. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:Ngadi Smart’s layered portrait of Sierra Leone’s complex water crisis

Mustapha Kamara, who is part of the Pewama community youth group, often helps to oversee the management and maintenance of the community’s water well. He is pictured holding a basket of palm kernels, which the community farms to produce and sell palm oil. ©Ngadi Smart

Source:

![Chernoh Sesay is pictured with his pepper plants. He is a farmer who plants rice and pepper, which he then sells to traders who visit the community. The water source he uses for drinking water is far away and dirty. Chernoh is married with five kids and is the main breadwinner. Sometimes he goes to fetch water for children to bathe in, or the children have to go to school without washing. Chernoh says politicians have come to the area to campaign about [the lack of clean water], but they have never helped. ©Ngadi Smart](https://www.1854.photography/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Copy-of-Ngadi_Smart_Port-Loko-District-Tombotima-Community_0G7A7378-8-300x200.jpg)

![Chernoh Sesay is pictured with his pepper plants. He is a farmer who plants rice and pepper, which he then sells to traders who visit the community. The water source he uses for drinking water is far away and dirty. Chernoh is married with five kids and is the main breadwinner. Sometimes he goes to fetch water for children to bathe in, or the children have to go to school without washing. Chernoh says politicians have come to the area to campaign about [the lack of clean water], but they have never helped. © Ngadi Smart](https://www.1854.photography/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Copy-of-Ngadi_Smart_Port-Loko-District-Tombotima-Community_0G7A7428-8-1-207x300.jpg)