The Slollaleia © Balfua

The new show at Nxt Museum in Amsterdam tackles the current age of machine learning and the role of artificial intelligence in image-making

In Still Processing, Nxt Museum’s latest exhibition, which opened 7 February and is on view through 5 October, artists Rosa Menkman and Sam Balfus aka Balfua delve deep into the shifting terrain of human-machine perception. Also part of Amsterdam Art Week, 20 to 25 May 20, the exhibition becomes a lens – albeit a fractured, prismatic one – through which we can witness the blurred boundaries between artificial intelligence, emotion, and image-making, curated by Bogomir Doringer.

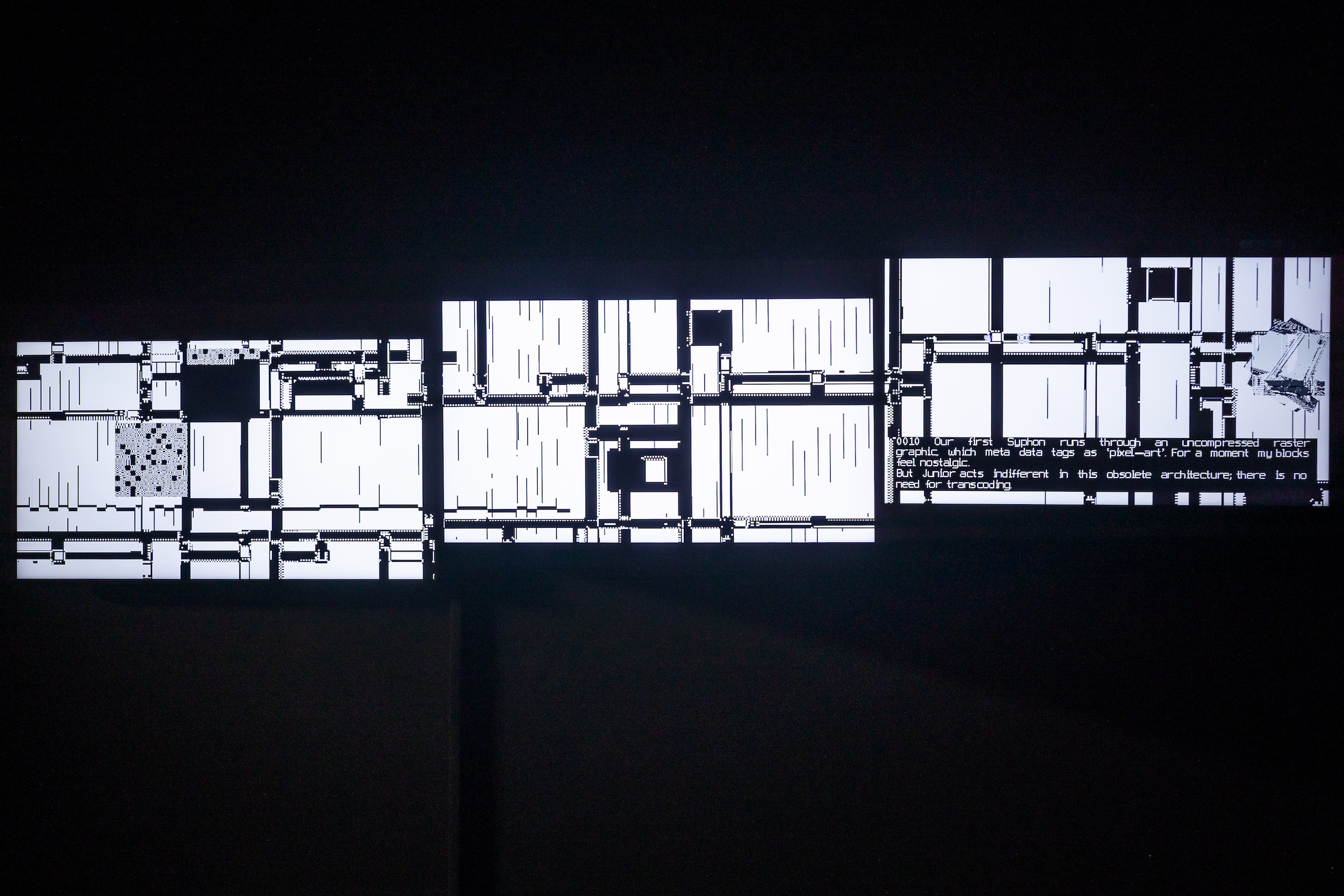

Known for her pioneering work in glitch aesthetics, Rosa Menkman traces the invisible ruptures of image-processing history. Her seven featured works, including The Collapse of PAL and IM/POSSIBLE RAINBOWS, act like archival fossils of digital evolution, capturing the compromises and colours lost in translation as technologies transition. In Menkman’s hands, image degradation becomes both critique and poetry, pushing us to question not just how we see but what we miss.

Just a few steps away, Balfua – who recently collaborated with Björk at Centre Pompidou – opens a portal into The Slollaleia at Nxt Stage. It’s a dreamlike realm where AI and analog blur into myth. With roots in performance, animation, and digital world-building, Balfua’s new commission is populated by surreal animalistic creatures that constantly shapeshift to eerie sounds with logic-defying fluidity. Their chimeric forms feel familiar yet unplaceable, like dreams.

“Copying as a creative, exploratory, and educational act is free and encouraged, provided that proper accreditation is given”

– Rosa Menkman

Elsewhere in the show, Boris Acket slows time to a crawl in Duration, a vast, echo-driven sculpture where sound unravels into shifting light. The installation presents an altered state where time becomes tactile, elastic, and hypnotic. Gabey Tjon a Tham channels the intelligence of the swarm in Red Horizon, a kinetic ballet of pendulums that sketch patterns in motion. Alongside Polynode XI by Lumus Instruments – an ambient dialogue between light and sound – the works unravel our sensory logic, inviting us to feel before we understand.

Children of the Light conjure a gravitational spectacle with ALL-TOGETHER-NOW, an installation inspired by the first image of a black hole. Five floating rings exude a cosmic rhythm, bending both space and sense in a meditative orbit of light. Geoffrey Lillemon turns spectacle inside out in Simulation in Blue, where AI-generated avatars writhe through a fever dream of digital cabaret. It’s part hologram, part hallucination.

Together, Menkman and Balfua stand at the forefront of a new artistic language where glitch and generation, failure and fantasy, become tools to make sense of a world still buffering. Here, they tell BJP about the processes behind their projects.

Rosa Menkman

Dalia Al-Dujaili: Your work in Still Processing traces key moments in the evolution of image processing. What motivated you to focus on the compromises that arise during technological transitions, and how do these themes manifest in your pieces?

Rosa Menkman: In 2015, I came across Joseph Goguen and Rod Burstall’s concept of “institutions,” which formalises how different logical systems can be translated and adapted across various domains. Although it originates in computer science, their focus on compromise during the translation process resonated with me; I saw a parallel in the way new image-processing standards inevitably come with trade-offs. While each new phase of image processing promises greater clarity or efficiency, they also inevitably lead to the obsolescence of older modes of working.

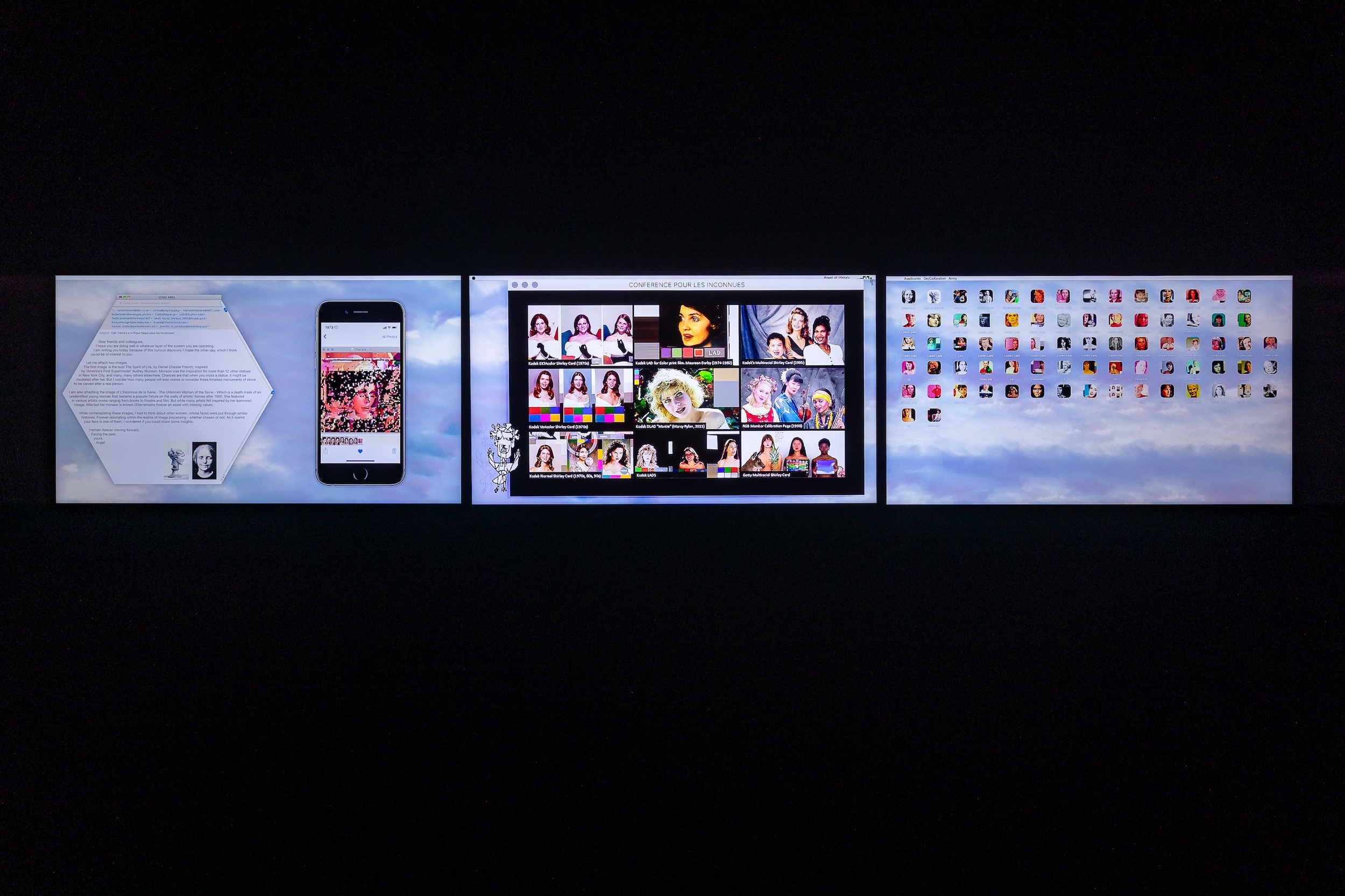

This concept is key to my work Destitute Vision which is the name for the collection of works on display in Still Processing. Destitute Vision is a four-chapter piece, illustrating the role of compromise in different phases of image processing. Throughout these chapters, I map how each shift – whether from analog to digital, from static to synthetic images, or through compression and platform-based dissemination – inevitably demands certain trade-offs, leading to obsolescence, bias or loss of other modes of rendering.

Across all these stages, I underscore how the pursuit of “higher” or “better” resolution can overshadow valuable older techniques, raise new biases, or reframe authenticity and authority.

The recurring figure of the Angel of History and her sigil (compass) unites these phases, prompting viewers to consider what we lose – and gain – each time we reinvent how images are produced and perceived.

DA: IM/POSSIBLE RAINBOWS examines how pollution and technology alter our perception of rainbows. Could you discuss the research and creative process behind this piece and what you aim to convey about the intersection of nature and technology?

RM: IM/POSSIBLE RAINBOWS is an installation developed from the research I did during my 2023 artist residency in Enter the Hyper-Scientific at EPFL (Lausanne, Swiss). The research is told from a near-future scenario, a media archaeologist has compiled an atlas of lost or unknown ways of seeing. She becomes fascinated by a NEON Rainbow Fairy Light, an artifact seemingly taken from a child’s bedroom. This object exemplifies the decline of nature’s original “glitch,” the atmospheric rainbow.

Rainbows have become rare due to a twofold “pollution”: on the environmental side, climate change and light pollution have dulled their brilliance, making their sightings increasingly unusual; on the digital side, generative AI confuses symbolic “rainbow-like” imagery with actual atmospheric phenomena, turning authentic depictions into anomalies.

DA: In DE/CALIBRATION ARMY, you address biases embedded in image-processing algorithms such as ChatGPT. What led you to explore this topic, and how do you envision this work contributing to conversations about technology and societal biases?

RM: Over the years, I have found many different instantiations of imagery of my own face used without permission or accreditation. I believe and publish with a Copy <it> Right ethic:

“First, it’s okay to copy! Believe in the process of copying as much as you can; with all your heart is a good place to start – get into it as straight and honestly as possible. Copying is as good (I think better from this vector-view) as any other way of getting there” – Phil Morton (1973).

To me, this means that copying as a creative, exploratory, and educational act is free and encouraged, provided that proper accreditation is given. However, when copying transforms into commodification and profit is anticipated, explicit permission must be sought, and compensation may be requested.

DA: Reflecting on your nearly two decades of expertise, how have you seen the relationship between humans and machines evolve and how is this evolution reflected in your current work?

RM: There has clearly been a huge shift in how humans and machines work and understand image resolution. In the early years, we were primarily concerned with mechanical or analog-to-digital transfers, optimising lens quality, sampling rates, noise reduction, and other variables. Even then, there was a tension between the need for fidelity and machine constraints on memory, processing power, or algorithmic precision.

With the introduction of increasingly complex AI and data-driven models, image processing has become less like capturing but rather something else. Slowly machines no longer just enhance our vision, but actively shape and form it.

While the human-machine relationship initially resembled capture; today machines shape our image of the world. I think there are two main phenomena that could illustrate this shift: obsolescence as ruin and algorithmic myopia and partial formation of sight.

In my current research, I combine these experiences – understanding ruins as memory traces of technological paths and investigating AI’s capacity for both clarity and distortion.

My work remains focused on understanding precisely how these ways of seeing take shape, calibrating and re-calibrating and de-calibrating them, so our own human vision doesn’t get superimposed and lost within the algorithm.

Balfua

Dalia Al-Dujaili: In The Slollaleia, you introduce a digital world inhabited by shape-shifting creatures called slollas. Could you elaborate on the inspiration behind creating these unique entities and the narrative they embody?

Balfua: I have always been inspired by world builders like Miyazaki, Dr. Seuss, Tolkien and Pendleton Ward and I take a lot of inspiration from fantasy and mythology in general. When I first started making slollas they were much simpler, similar to graffiti tags. They developed over time and their forms became fuller and more complex and I began to ascribe them specific traits and personalities. I think of them as abstract spirits, with lives and magic that exist beyond our worldly plane. In the sayssiworld (my digital/abstract spirit world) they don’t require any distinction; they can exist in their purest form… and we humans can interact with them however we like.

DA: Your work seamlessly blends traditional and digital tools. How did you approach integrating these mediums in “The Slollaleia,” and what challenges did you encounter during the creative process?

B: I spent some time training AI models on my 3D rendered work, so it was a fun challenge to work with both techniques in the same projection space. There’s something really weird and interesting about seeing how the machine reinterprets your own imagination. I think I was trying to keep a certain level of coherence, while also trying to push or lean into breaks and glitches in the software, and addressing those with sound. I think the challenge was mainly figuring out how to compose everything around the specific requirements of the space, working with the projection on the wall and the floor for the room-scale video installation.

DA: Collaboration has been a significant aspect of your career, notably your recent project with Björk at the Centre Pompidou. How did that experience influence your approach to The Slollaleia, and what insights did you bring to this installation?

B: Working with Björk was awesome, we have a very similar thought process in terms of creating and playing with feelings. I think we both kind of treat sound and visuals as the same thing. In the collaboration for the Centre Pompidou we were trying to paint visuals that really resonated with the layers of sonic-architecture she had been building, with her voice and the recordings of endangered animal sounds. For The Slollaleia, my thought process was a bit more abstract, sort of thinking of the installation as a living organism, making sure it breathed and putting space or busy-ness where it wanted it.

DA: The Slollaleia reflects on the constant flow of information and the unpredictable nature of our interactions with technology. What message or reflection do you hope visitors take away regarding their own relationship with the digital world?

I don’t have any particular message to disseminate, but I definitely hope that people leave feeling smacked by a certain sense of awe. I grew up in the digital age and I definitely feel the effects of social media on a daily basis, on my attention span. For me the Sayssiworld is just as beautiful and terrible and complex and under or overstimulating as our world. There’s a lot of lore behind the Sayssiworld and the slollas that I don’t reveal in the piece, but I tried to present it in a way that lets you know it’s there if you’re interested, that there’s something large and inexplicable behind what you’re seeing and feeling.