© Bettina von Zwehl

Exploring the wunderkammer collection that underpins University of Oxford’s museum, The Flood recreates part of its magic – and uncovers some moral failings

“In the 17th century the elephant was brought to Europe via trade routes, but Europeans didn’t know anything about them, so they fed them things like wine and wondered why they died shortly after,” says Bettina von Zwehl. “If they survived the journey, they would end up caged in princely courts. Now all we have left is the ivory and the complex conversations: should we conserve the ivory, should we display it, or should we burn it all? Should we destroy all the ivory in the Queen’s collection, or should we hide it in the basement, and pretend we don’t have it?

“Ivory is all these questions at once,” she adds. “If you go to these collections, they’re full of ivory objects. But you often don’t see it. It’s hidden in the object. You think about craftsmanship, what a skilful artist of the 17th century that was. You don’t see the slaughter and suffering and violence. Nobody thinks of the elephant.”

Von Zwehl’s practice does not attempt to explain museum collections; instead she “translates some of the madness”. The multidisciplinary artist keeps returning to the wunderkammer, early modern cabinets of curiosity which housed items collected from across the world. She has investigated collections at the V&A, Freud Museum, Queen’s House (all in London) and now, the Ashmolean, University of Oxford’s art and archaeology museum. With the museum acting as both site and subject, Von Zwehl’s solo exhibition The Flood delves into its hoard. On display until 11 May 2025, the show includes gilded mushrooms, tail feathers of a phoenix, imaginary insects, peach stones, stage maquettes for imagined plays, and new photography.

“The Flood taught me that my medium is not photography. My medium is the museum itself”

“I don’t want to illustrate issues,” the artist explains. On her bookshelf, Ashmolean catalogues stand dog-eared and bookmarked, notes sprouting from the pages. “I’m not interested in illustrating politics. I care about association, challenging the viewer by throwing questions on the wall which they must decode. The wunderkammer is about decoding. It demands curiosity. What kind of philosophical questions were relevant in the 17th century? How can we decode them, and make them relevant again?”

This is not a history lesson. Von Zwehl strives to recreate the feeling of the wunderkammer while reflecting on their complicated origins. “It’s entangled with colonialism and the exploitation of people and species. Yet they also hold curiosity and wonder and alchemy and magical thinking, a totally different set of belief systems. The early collections were not archives at all. Pre-scientific… greedy,” she says. The Tradescants, the collection’s founding family, called their cabinet ‘The Ark’; a message was sent out: ‘Bring us everything strange and unusual from your travels.’

“It was very much about accumulation and amassing, the weirder the better. In those early cabinets, people were touching things, opening the drawers. They were slipping things in their pockets. It must have been quite chaotic and wonderful and obviously problematic, but a very exciting place to be,” Von Zwehl adds. “But it existed in a disregard for where the objects came from. That’s the entanglement – colonialism, slavery and theft. If you look at the benefactors listed in the catalogues, you can smell it.”

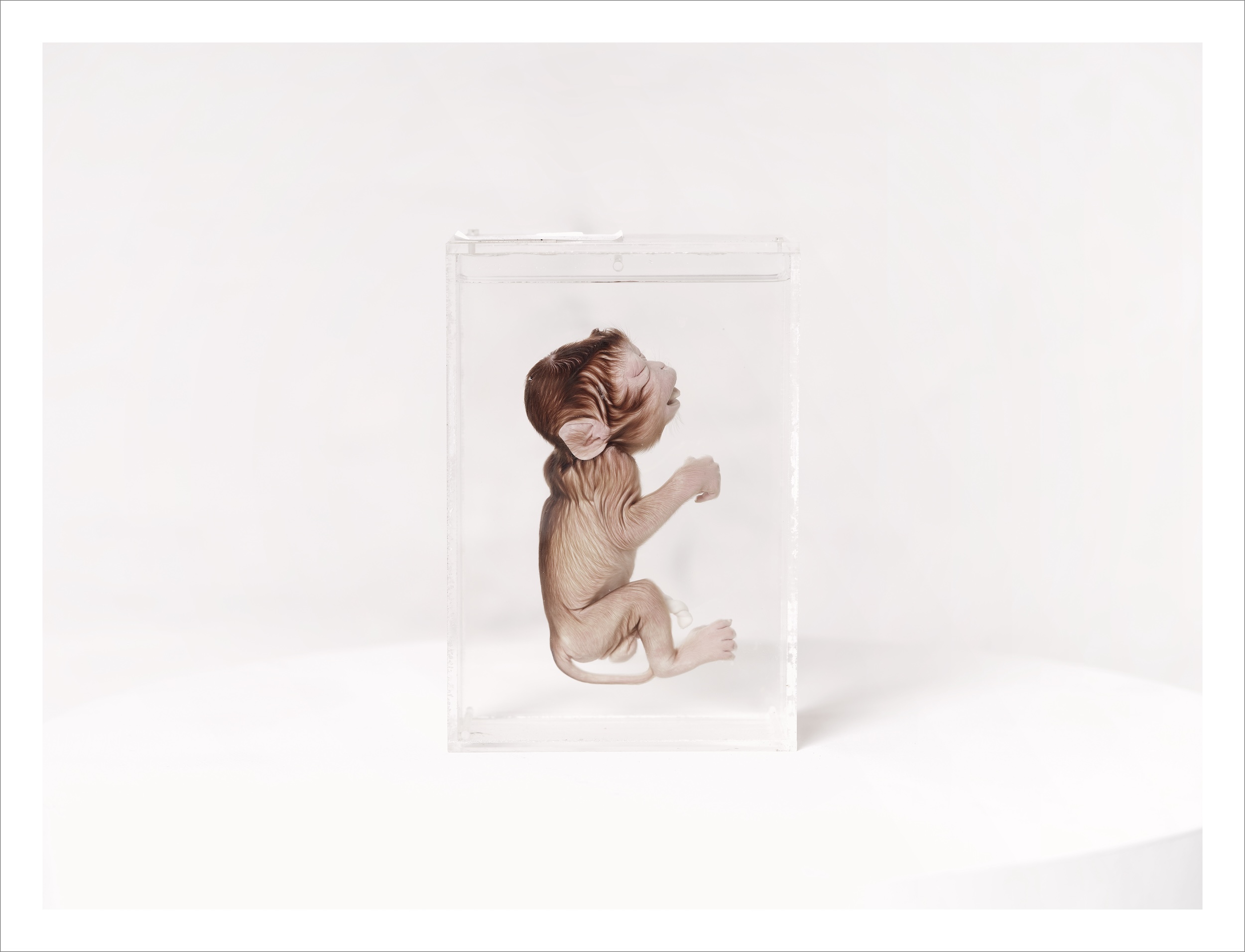

The Flood was a year in the planning, with Von Zwehl undertaking an Ashmolean residency throughout. Much of the early collection consisted of natural history; plants, insects, soft tissue. Over the years these materials have perished, leaving gaps in the cabinet. The title refers to this loss, a deluge wiping it all away, forcing one to make sense of the wreckage and rebuild the cabinet. “The Flood for me is about loss and dispersal and destruction and reorganisation,” she says.

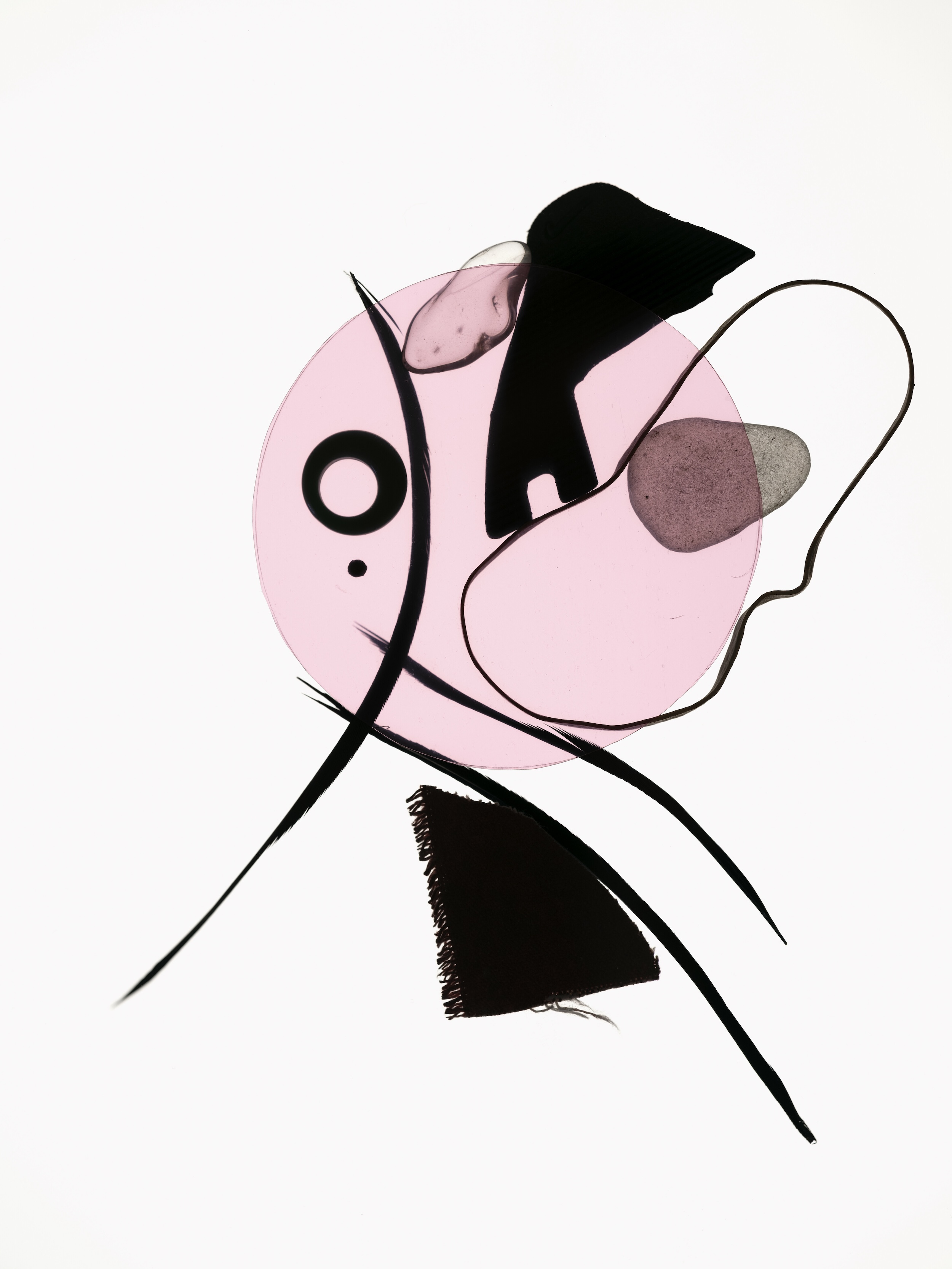

“I took pictures of specimens at the Museum of Natural History, some of which have become wallpaper in the gallery, which I then created collages from. So you see these large wallpaper images, and then around them are photographs in dialogue. But it’s not always clear. You need to decode it.”

In this flood, photography is the raft used to get to the other side. But it is just a raft. It is not something to be revered and once VonZwehl reached the other side, the raft had served its purpose. “[The Flood] grew through different phases of working and battling with photography,” she explains. “I have an ambivalent relationship with the camera. I don’t love photography. I think it’s a very problematic medium, but also a fascinating one. Having worked with it for so many years, I’ve reached a point where I finally understand what I love about photography: how it communicates with the non-photographic. Suddenly, then, you have a story,” she explains.

Von Zwehl collaborated with opera designer Robert Innes Hopkins to create her own maquette with the images; in Remember Me, Remember Me? the artist ponders the mysterious life and death of Hester Pookes, the wife of Ashmolean founder John Tradescant the Younger, who drowned in her garden pond. Pookes had been involved in a legal dispute with Elias Ashmole, a wealthy neighbour and collaborator of her late husband. Despite the dying wishes of John Tradescant, Ashmole eventually took control of the entire collection, fused it with his own, and gifted it to the university – birthing the Ashmolean Museum.

On a model of a 17th century opera stage, two golden chairs face each other, a crystal ball in the middle, all floating on black sand. A photograph of a woman turned upside down hangs behind. “I wanted a homage to Hester,” says Von Zwehl. “I think it’s one of these millions of stories of women being sidelined in history. What was her role in this collection? What was she doing? The chairs are me and the writer Sophy Rickett, talking about Hester with a crystal ball between us and the image.” The crystal refracts, yet physically separates the three women. “The piece is a conversation, like everything else is a conversation piece. Everything in The Flood talks to everything next to it.

“The Flood taught me that my medium is not photography. My medium is the museum itself,” she adds. Von Zwehl enters the wunderkammer more like an alchemist than an archivist. Magic is constantly afoot; in preparation for the exhibition, Von Zwehl consulted a tarot reader, who immediately pulled The Magician card. The Magician acts as the bridge between the spiritual and material realms. In front of him are an array of items, symbolising each element. With these, he has everything required to manifest his intentions into the world. “The reader said to me, you have everything in front of you. Now, you just need to do it.”

Bettina von Zwehl – The Flood is at the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, until 11 May 2025