© Sofiia Vinnichenko

Through family archives and new images, Postponed Disbelief explores memory, language, and the impact of conflict

Sofiia Vinnichenko always knew she wanted to study photography. Born in Kyiv, she also knew she would need to move abroad to do so – there were (and still are) very few photography degrees in Ukraine. She decided to study at Berlin’s University of the Arts and, in preparation, took a degree course in linguistics, which allowed her to learn German.

In February 2022, Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, forcing her to flee to Germany ahead of schedule and finish the linguistics course remotely. Studying art in Berlin didn’t work out, so she moved again, this time with just a month’s notice, after winning a place on the prestigious MA photography course at London’s Royal College of Art. She also received support from Düsseldorf’s nonprofit charity and gallery, fiftyfifty. Earlier this year, she graduated with a final project that won the Shadow Labs Award.

“This also relates to a lot of cultural heritage that was destroyed in Ukraine, generation by generation, because the Russian language was imposed”

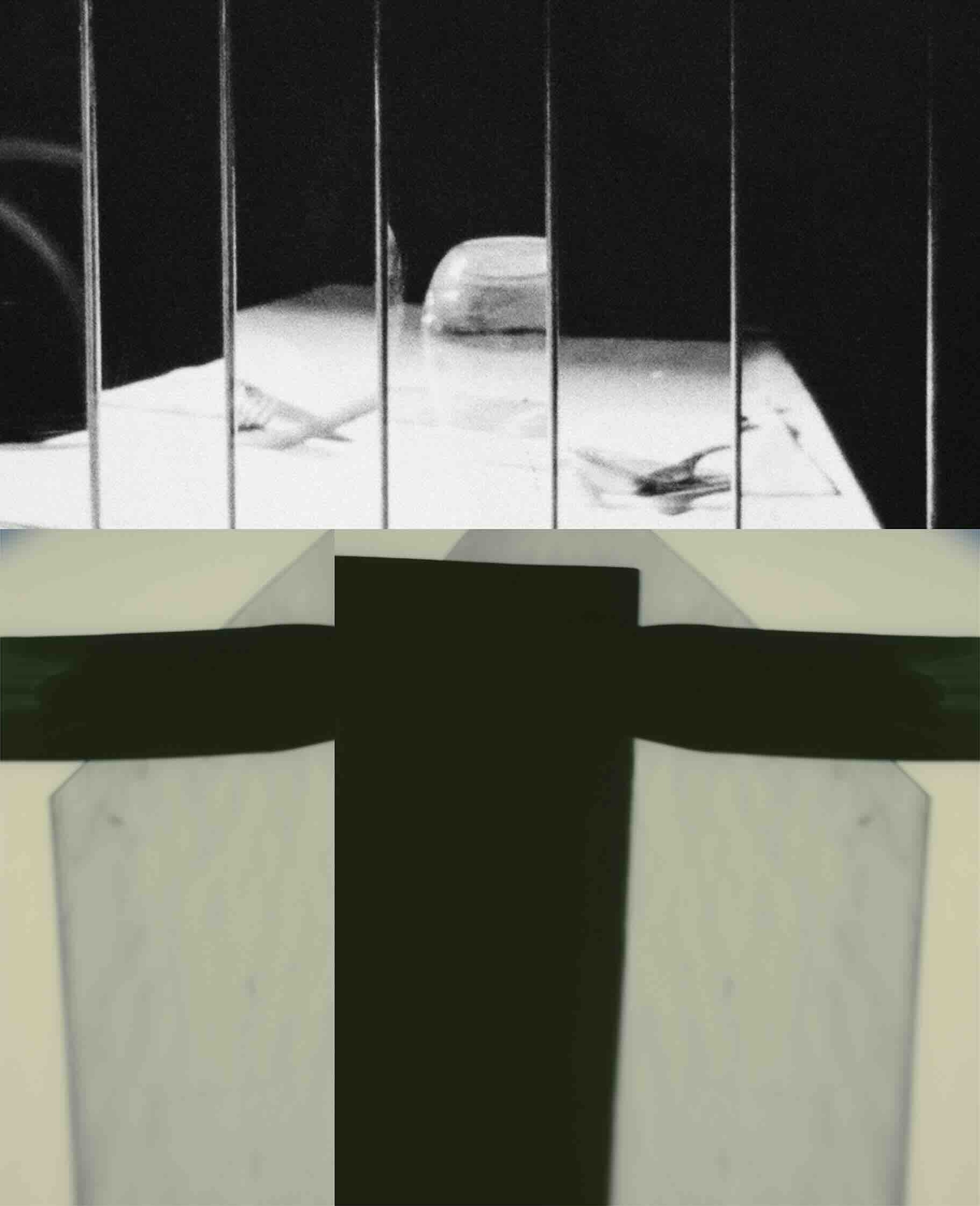

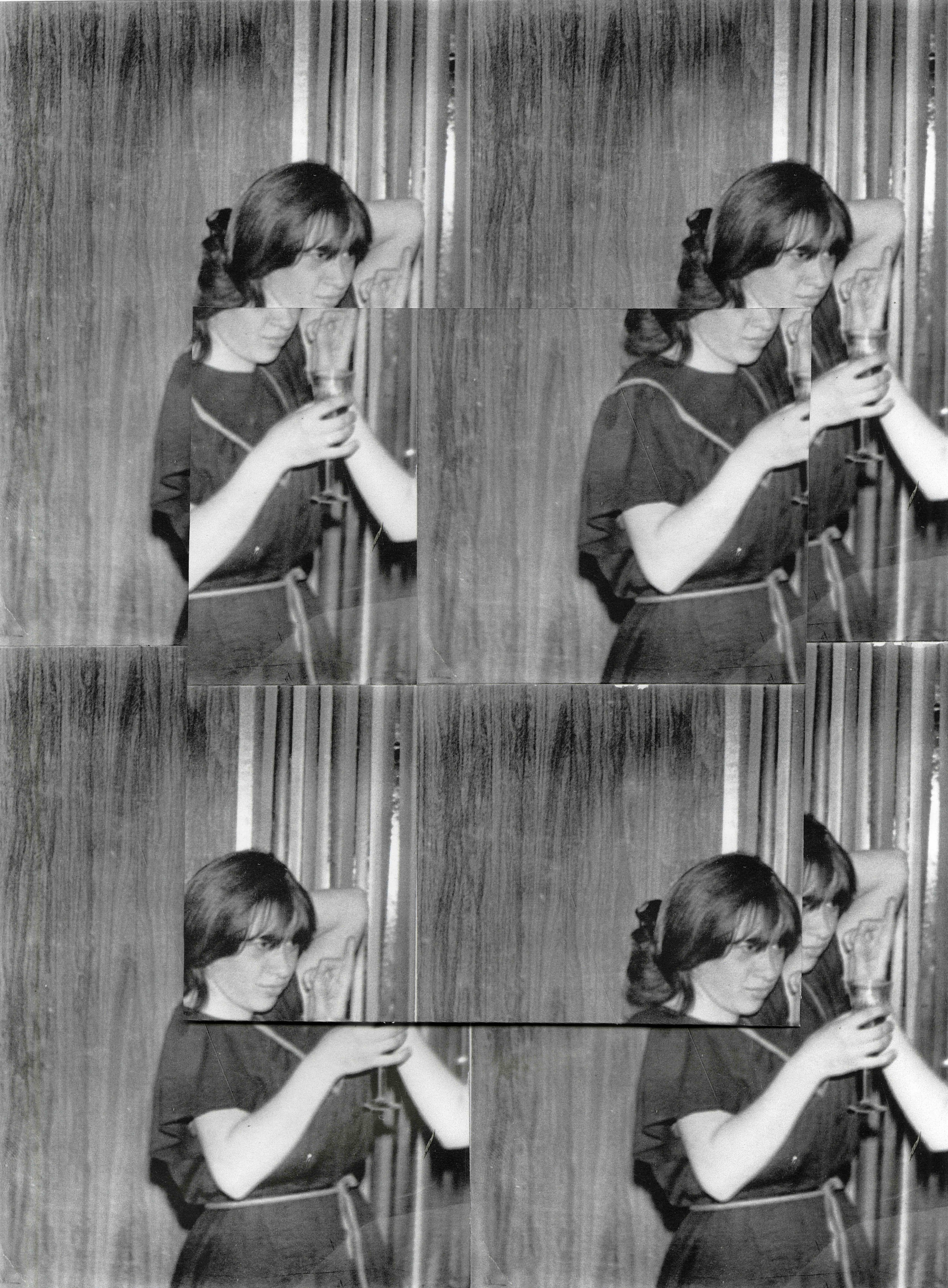

It is an extraordinary story of determination and pure grit, but Vinnichenko’s series is even more unusual. Titled Postponed Disbelief, it is a mix of her own images and family photographs. Some of these images are scanned into multiples and transformed into uncanny collages. A meditation on photography as a medium, her series also reflects the psychological impact of war.

“I first started working with family photographs in 2022,” she explains. “I became interested in working with archive materials from my family, who were still in Ukraine. I have been back twice, both of which were approximately OK because there weren’t many bombings – or not as many as there could have been – and I brought back photographs.”

“The repetition is about routine,” she continues. “I focused on routine because it was completely lost in the beginning [of the war], especially after the full-scale invasion. Routine is something that gives us normality. But seeing so many people dying – even children dying – the abnormality reached such a high level. It was almost like two separate worlds. For example, when we fled Ukraine, I went to change some money, and the woman in the bank was wearing make-up and laughing. And I felt like, how could she live? For me, life had stopped. I couldn’t understand how people were still going on living.”

Like the images in Vinnichenko’s series, her story has deeper layers. Along with many Ukrainians, she grew up speaking Russian, a legacy of its imposition as the official language for years. Ukrainian was her second language (English her third, and German her fourth), but she has now rejected her mother tongue. She refuses to use it, even with her family or in her diary, which only she reads. She is aware that this rejection distances her from part of her past, but by using archive images, she hopes to reclaim those early years.

“The family photographs I am working with belong to a past that was in Russian,” she explains. “By using them, I can translate a visual proof of the past, the way I’ve learned to translate my memories, which are stuck in the language I don’t use anymore. But this also relates to a lot of cultural heritage that was destroyed in Ukraine, generation by generation, because the Russian language was imposed.”

Having studied linguistics, Vinnichenko is well aware of the idiosyncrasies of photography as a language – for example, its inability to generalize from the particular, as it documents scenes from life. Using repetition pits her against the medium’s boundaries, but it also helps her understand photography as a system for describing the world. For her, this exploration is not purely formal or academic; it is deeply personal. The attempt to find meaning has become crucial as her familiar life fell away and her country slid into incomprehensible violence.

“It’s difficult to describe in words,” she says. “It feels like freefall. Like we live a long life, but at the same time, since the universe is so big, it’s always just one moment that has already passed. I have this feeling of eating yourself and giving birth to yourself at the same time – of reaching toward something real, but not being able to reach it. But humans learn through repetition, and repetitions can become rituals and even religions. So I am trying to find something that will stand for belief, for something solid in this massively huge, infinite world.”