All images © Santiago Escobar-Jaramillo

The photographer worked in collaboration with coastal communities in Colombia to advocate against the devastating effects of narcotics

In September 2022 Colombian president Gustavo Petro addressed the United Nations, demanding, “From my wounded Latin America” that the war on drugs be abandoned. “Reducing drug consumption does not require wars, weapons; it requires all of us to build a better society, a more supportive, more affectionate society, where the intensity of life saves us from addictions and new forms of enslavement,” he stated. Santiago Escobar-Jaramillo’s participatory project, The Fish Dies by its Mouth (‘El pez muere por la boca’), can be read along similar lines, illustrating the devastation the illegal drugs trade has brought to Colombia, but also advocating for a new and better way to relate to each other.

Escobar-Jaramillo created the work in collaboration with communities in two coastal villages – Rincón del Mar and Bahía Solano. Rincón del Mar looks out to the Caribbean and Bahía Solano towards the Pacific; each has its own distinct culture and traditions, but both are also on the frontline of the Colombian drug trade. Cartels maintain control of these areas with violence and paramilitaries, and their leaders assume autocratic, sometimes absolute power. In Rincón del Mar the paramilitary Rodrigo Mercado, AKA Cadena, had a junior school knocked down because it spoiled his view of the ocean; in Bahía Solano, Hernán Velez ordered hotels be built for his visits.

“We are used to talking about these topics in a very masculine way, a stereotyped way of thinking about Pablo Escobar and the narcos. But what happens when you try to put the attention on the communities”

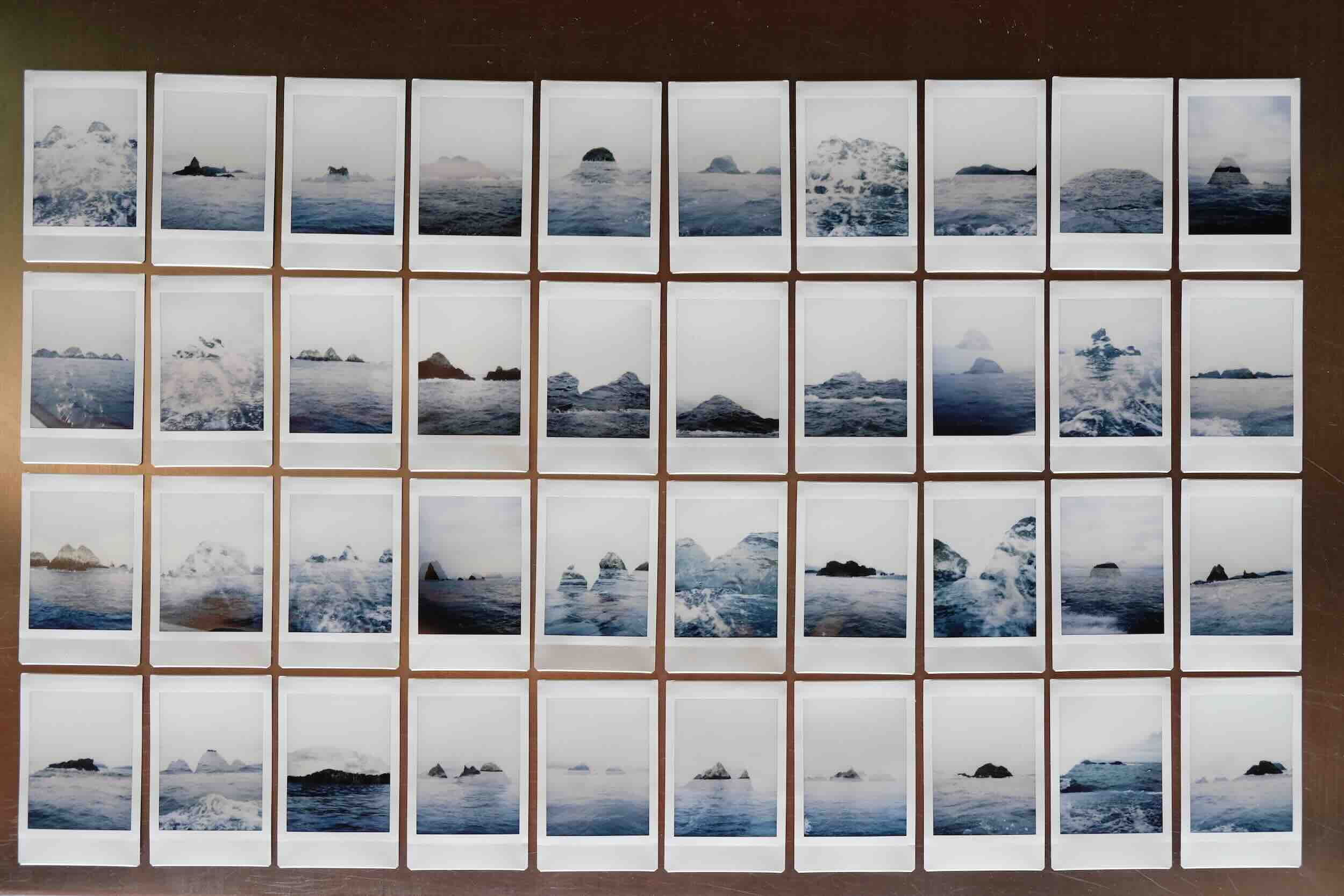

Escobar-Jaramillo grew up in Manizales, but his uncle had a cabin in Rincón del Mar, and he has visited the village since he was a child – except for the period from 2000 to 2012, when the paramilitaries banned outsiders. Reconnecting with local friends Federico Martínez and Deivis Vecino Altamar, he wanted to foreground their perspectives. “I’m talking about a difficult issue, about drugs, drug dealers, violence, paramilitaries,” he says. “We are used to talking about these topics in a very masculine way, with weapons, violence, blood, a stereotyped way of thinking about Pablo Escobar and the narcos. But what happens when you try to move it from that perspective and put the attention on the communities, on their resilience and resistance, on their daily lives, their celebrations, music, dance, gastronomy, architecture, even whale sightings?”

Working with his friends and their families for eight years – and adding trips to Bahía Solano – Escobar-Jaramillo has created something more playful, and more egalitarian. One image shows Martínez and Vecino Altamar posing in the sea, the former sporting a T-shirt refashioned to look like fish scales, the latter raising his hands to form a nautical flag, a symbol of resistance. Another shows a kid pretending to be a fish; the child is the nephew of another friend and is a similar age to Escobar-Jaramillo when he started visiting. At the same time, the photographer shows the insidious impact of the cartel. There is a short of Martínez wielding coral as if it is a gun, at Isla Palma, which was owned by notorious cartel leader Pablo Escobar in the 1980s; Escobar-Jaramillo says he laughed at the childish gesture, then realised it reflected a backdrop of violence.

Escobar-Jaramillo also photographed locals with their faces concealed, scarves protecting their identities. These locals have found packages of drugs, lost or perhaps jettisoned at sea; by selling them, they can earn a year’s wages, but risk incurring the wrath of the paramilitaries. “Years ago I was in Bahía Solano with my father, my brother, my uncle, my cousin, out on a fishing boat,” Escobar-Jaramillo explains. “This guy told us, ‘Look, this is the pesca blanca’, the white fish – a package of cocaine floating on the sea. If a fisherman finds one of these packages it can completely change their life. They can add another floor to their house or buy an outboard motor for their canoe. I can understand [why they might be tempted to sell it]. But others from the community don’t want to be a part of it, because they’re afraid or they don’t agree with the drugs trade.”

The fish of the title partly references this anecdote, but Escobar-Jaramillo thinks about fishing in other ways too. Westerners often do not consider where drugs come from, or the impact of the drugs trade on South America, he points out; he aims to lure in viewers with this appealing, brightly coloured work. He has published a photobook of the series – which features ‘scales’ cut into the cover – and made multimedia installations. In doing so, he hopes to ‘fish’ for attention, and get people to think about the individuals at stake.

“Photobooks are part of this media mix, this media universe I am constructing,” he says. “I want to communicate, to help people keep memories and relate to others, and as a song to that undefined limit between sea and land, between legality and prohibition.”