© David Hoffman

A turbulent decade riven by social and political change, the 1980s were also fertile ground for British photography

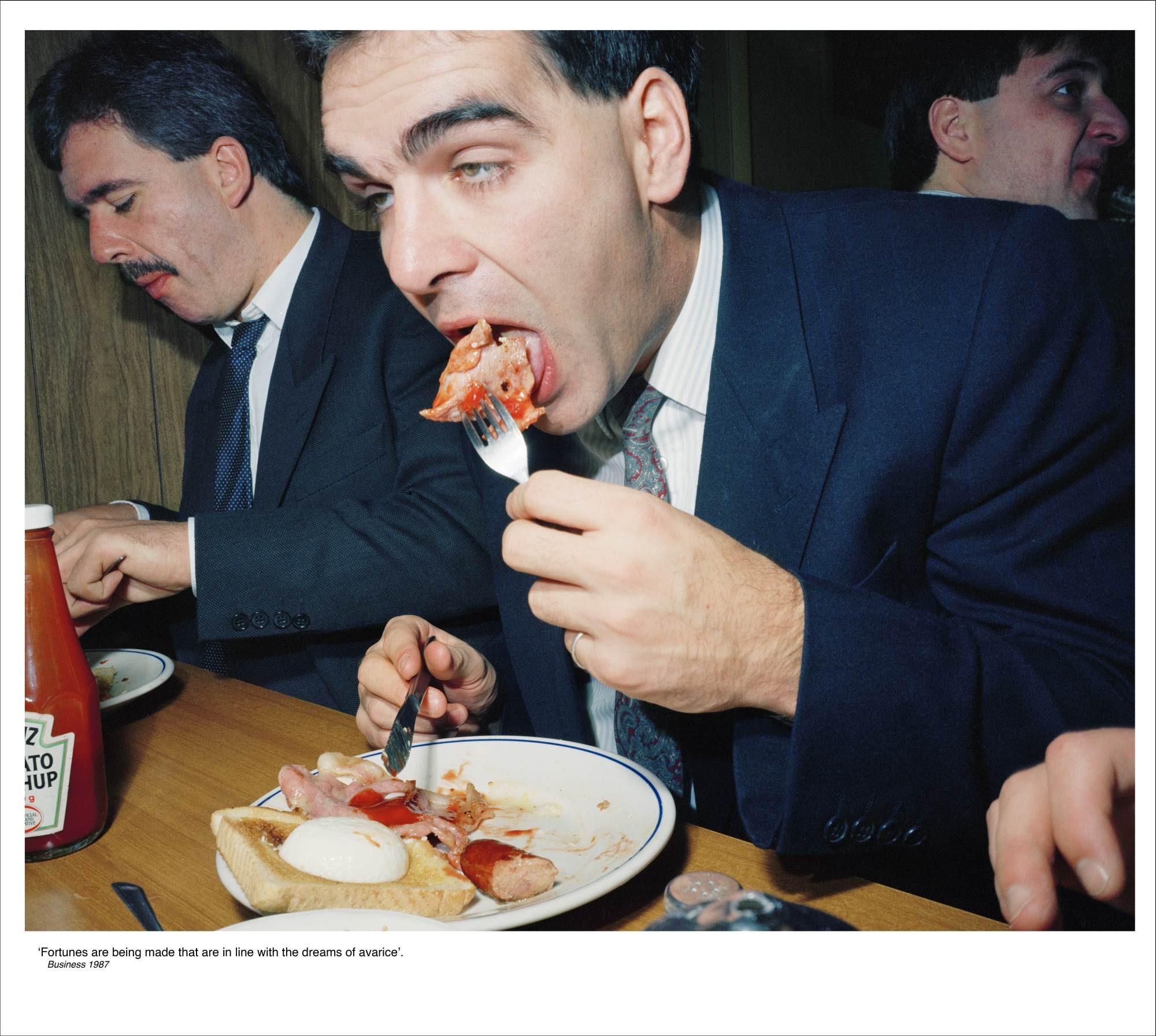

This autumn Tate Britain opened The 80s: Photographing Britain, a huge show exploring images and image-making at a critical juncture of British history. Spread over 12 rooms and featuring works by over 70 photographers, artists, and collectives – plus key magazines and journals – the exhibition spans what the curators define as “the long 1980s”, covering roughly 1976 to 1993. Marked by events such as the Winter of Discontent (a protracted period of labour disputes), the premiership of Conservative Margaret Thatcher from 1979–1990, race uprisings, the Miners’ Strike, the Troubles in Northern Ireland, and the Aids pandemic, this era was turbulent, and photography was used in it as a tool for social change and political activism – as well as artistic experimentation and theoretical questioning.

“We wanted to provide context on both sides of the 1980s because, of course, that period doesn’t exist in a vacuum,” explains Jasmine Chohan, assistant curator of British contemporary art at Tate. “The history, politics, social movements and photographic developments of the 1970s have such a large influence on the 80s.”

“How do these photographers navigate each others’ worlds and create quite a unified movement?”

– Jasmine Chohan, co-curator

The exhibition is the result of years of work spearheaded by Yasufumi Nakamori, now director of the Asia Society Museum, but from 2018 to 2023 senior curator of international art (photography) at Tate Modern. Surprised that the institution had not previously focused a show on 1980s British photography, he proposed one soon after joining and got the green light almost immediately. This allowed him to intensively research the period, including hosting workshops with image-makers and magazine editors from the period, plus specialist academics. Co-curated by Nakamori, Chohan, and Helen Little (curator of modern and contemporary British art at Tate Britain) the result is a nuanced survey which includes iconic images by Martin Parr and Chris Killip, but also situates them within a wider social and cultural history, and alongside less celebrated contributors.

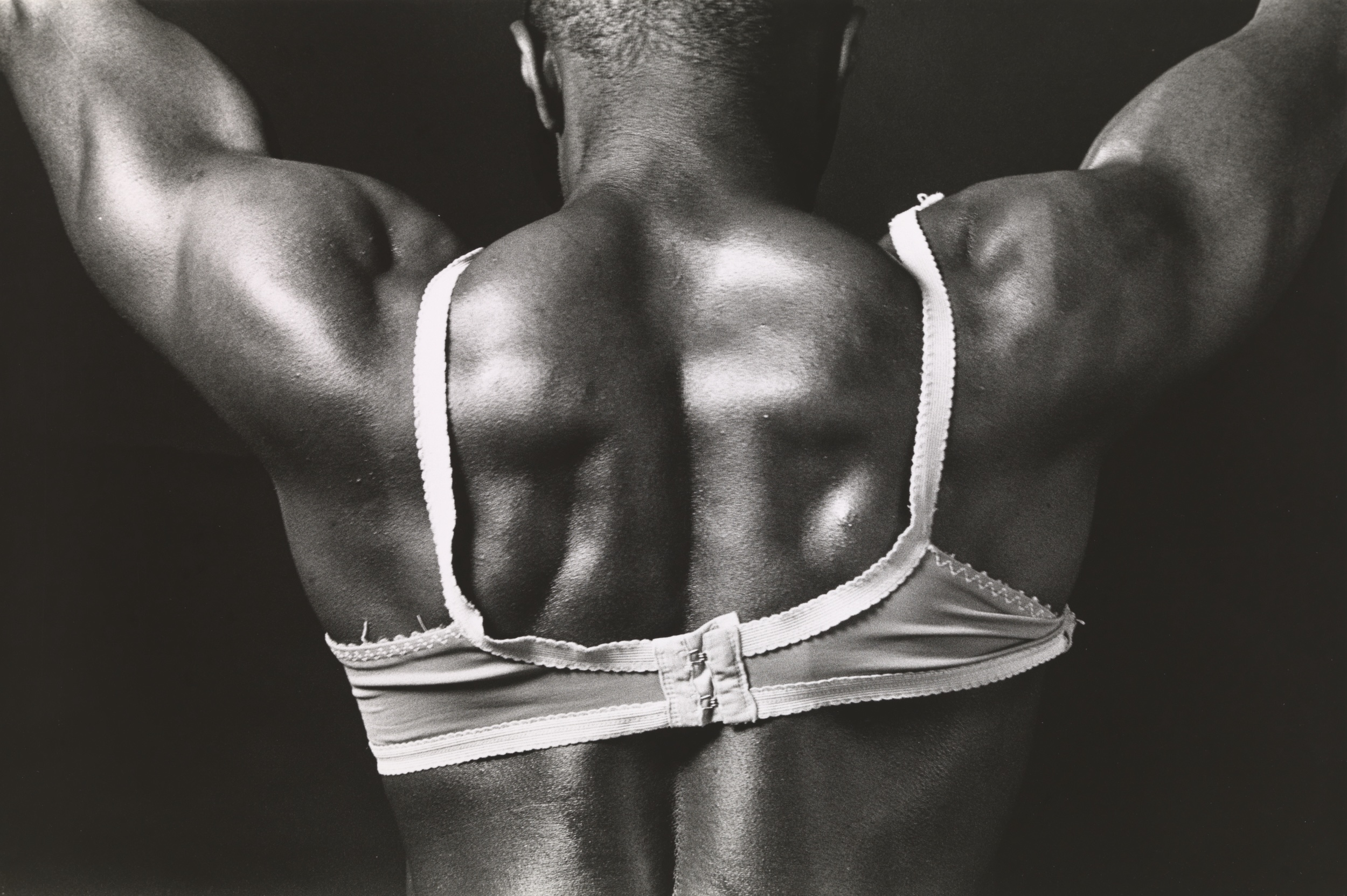

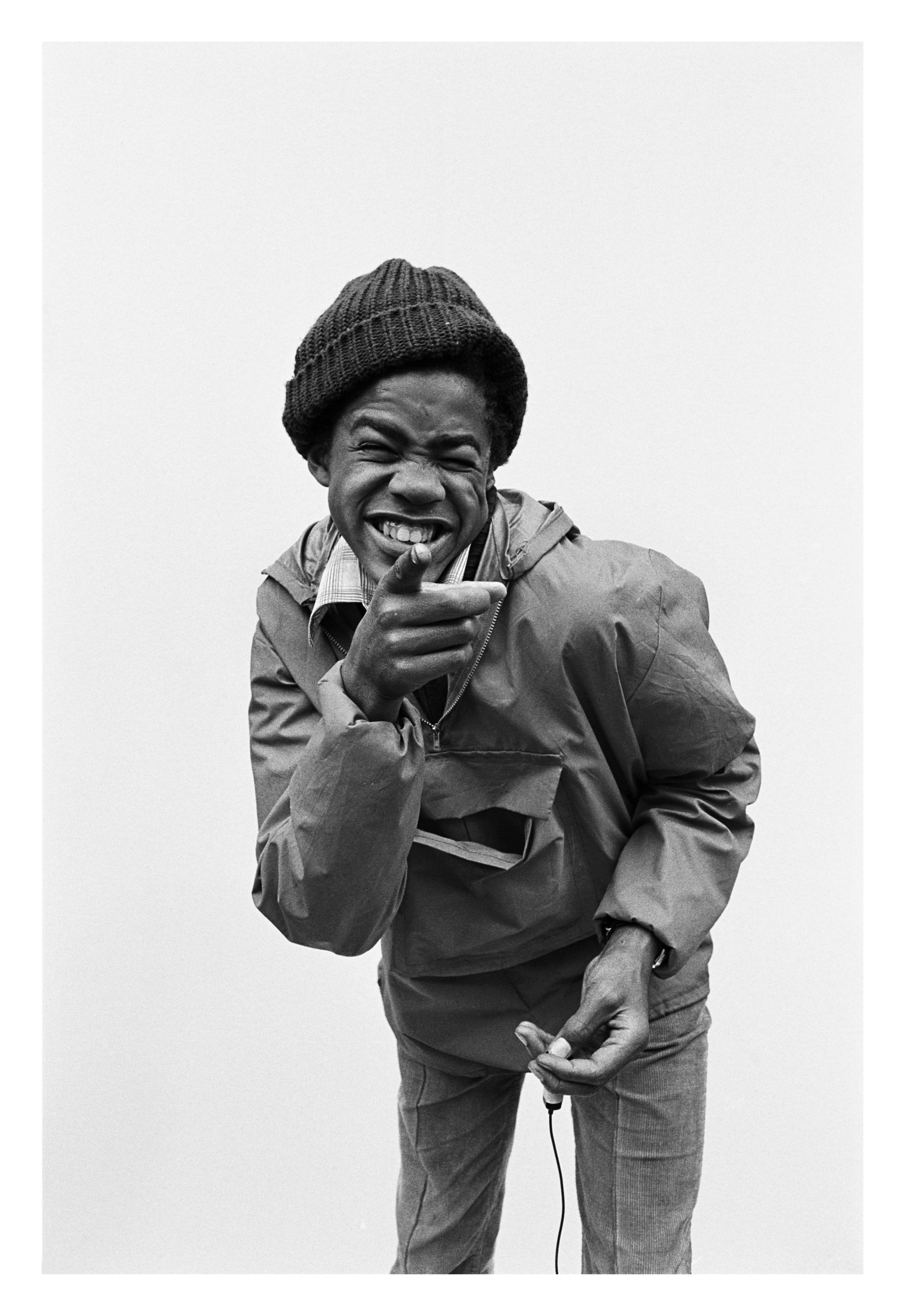

The 80s: Photographing Britain includes work from the Black arts movement, the South Asian diaspora, the queer experience, and various feminist coalitions. It also encompasses the development of magazines and organisations such as Camerawork, Ten.8, Autograph ABP (Association of Black Photographers), Half Moon Photography Workshop, and Hackney Flashers, as well as the impact of theorists such as Victor Burgin. The show considers how these elements work together, including a spotlight on reflections with Black experience, for example, but also contemporary critical thinking around the position of the photographer, and the possibility of building solidarity.

“It is something we have to unpick through the interpretation, but with Dennis Morris’ Southall – A Home from Home series, in which he photographed the South Asian community, we can consider: how do these photographers navigate each others’ worlds and create quite a unified movement?” says Chohan.

The exhibition also includes landscape photography and key technical developments, such as the introduction of colour, as well as the impact of style magazines such as i-D. Launched in 1980, i-D helped nurture the careers of Wolfgang Tillmans, Nick Knight, and Jason Evans, but also reflected increasingly popular approaches to both photography and politics. “A transition that we trace is how photography moves from these quite niche or particularly photographic groups through to something more popular and celebrated,” Nakamori explains. “By the 1990s you have a pop culture and an optimism emerging from countercultural movements that were very underground and very marginalised; you have queer clubs frequented by large parts of the population, for example, not just small communities. And photography becomes more fashionable, more colourful and bold.

![03 Jason Evans, Simon Foxton, [no title], 1991. Tate (1) (1)](https://www.1854.photography/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/03-Jason-Evans-Simon-Foxton-no-title-1991.-Tate-1-1.jpeg)

“It was a deliberate choice to finish the exhibition with that, after the sometimes quite heavy protests and so on,” he adds. “But even when we are looking at those protest movements, we have been careful to not fetishise the violence or the trauma of the period. We want to actually celebrate these community movements, and the power and the optimism behind protest too.”

For Chohan, that spirit is what makes the 1980s and 90s pertinent now, in another era of protest and political opposition. “There’s a bit of generational amnesia,” she says. “These discussions that happened in the 1970s and 80s have been totally forgotten about. Over the last five years we have started to have these conversations again, but by excavating these moments – reflections on Black experience, the political Black photography movement and the anti-racist movement, for example – we’re trying to show that these conversations have a very long history. Instead of having to redo a lot of that groundwork, there is material we can utilise and build on.”

The 80s: Photographing Britain is at Tate Britain, London, from 21 November 2024 to 05 May 2025

tate.org.uk