© Sara Benabdallah

The photographer reflects on her recent participation in the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair with Rand Al-Hadethi

There’s a communal celebration in Sara Benabdallah’s work — a quiet yet profound exploration of personal and collective heritage. Her images serve as windows into Moroccan womanhood, intimate family narratives, and artisanal culture, all interwoven to highlight broader cultural themes. Through vibrant compositions and carefully staged details, Benabdallah reflects on the continuity of tradition and its influence on modern identities. Her work not only documents but also invites viewers to engage with the complexities of Moroccan heritage — its beauty, its burdens, and the insights it holds for today, such as her Dry Land series, which was presented in Benabdallah’s recent showcase at the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London this October, amongst other work.

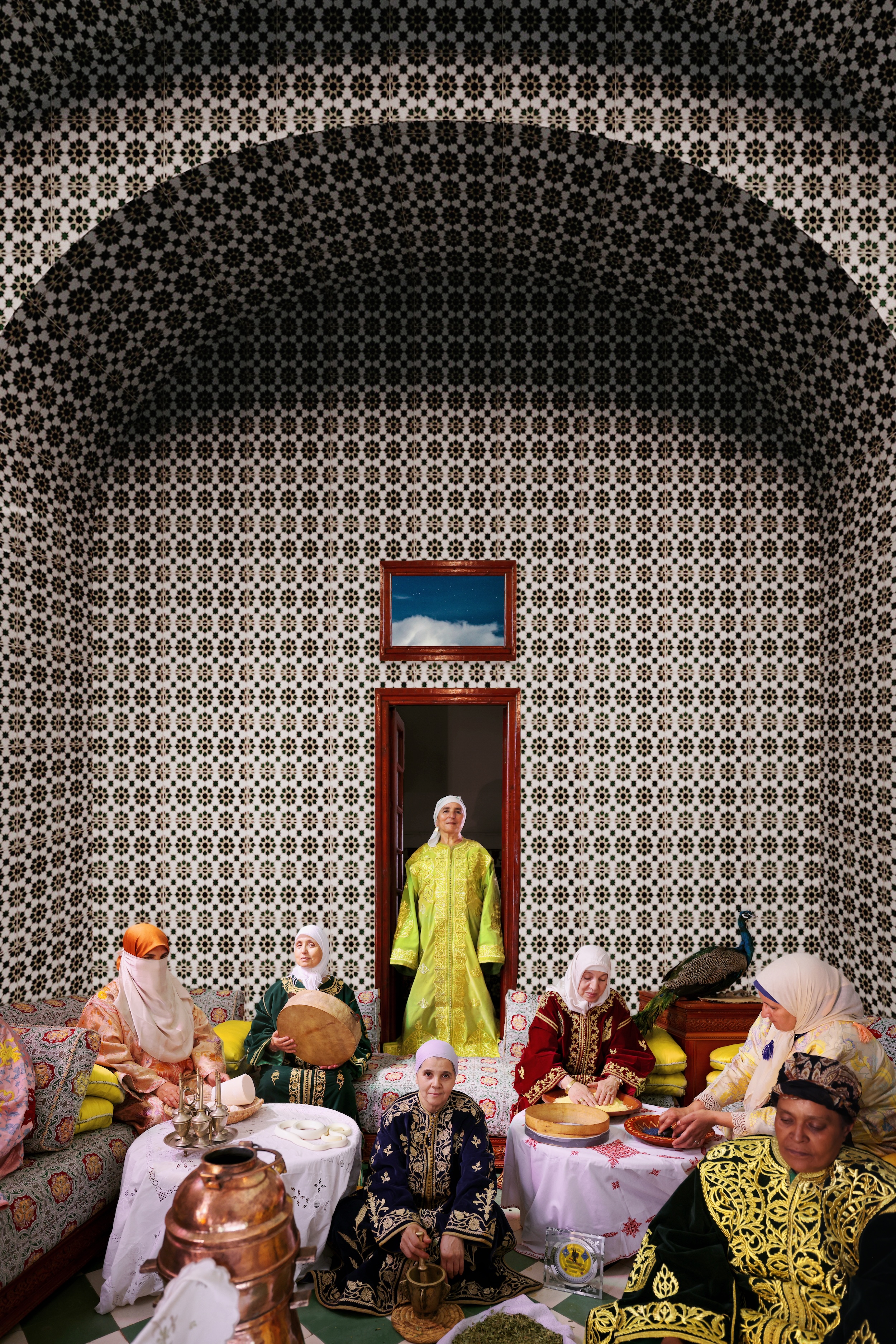

And in Fi Ghiabiha (In Her Absence), the layered tableau of women engaged in traditional domestic rituals offers a meditation on both the visible and invisible roles within familial spaces. What might seem like mundane, often overlooked routines, reveals the quiet labour required to sustain them – particularly in MENA societies, where mother-figures and women shoulder the unspoken responsibility of transforming a house into a home.

As the first and only international art fair dedicated to contemporary African art, the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, has become a vital platform for artists like Benabdallah. With three editions held annually — in London, New York, and Marrakech — alongside a pop-up fair in Paris, 1-54 takes its name from the fifty-four countries that make up the African continent. Benabdallah, who was born and raised in Marrakech before leaving to study at the New York Film Academy in NY and LA, and at Savannah College of Art and Design, made her 1-54 debut this year.

“Seeing how craftsmanship is slowly dying, and bringing that back and into 1-54 was also a really incredible feeling, because it’s something that’s beyond me or my work”

Photographing women has always been at the heart of Benabdallah’s creative vision, even before she knew how to fully articulate it. “When I was younger, like many other Moroccans or North Africans, we saw the West as this big thing. I wanted to leave Morocco. All I wanted to do is go live in New York and be in America, and I was infatuated by Hollywood’s culture,” she shares. However, half way through her 10 years in America, she found herself struggling. “I lost a lot of my identity, and I didn’t know what kind of stories I wanted to tell,” she admits. “It felt like everything that I’ve done was wrong, every movie, every picture that I’ve made, was missing something. It wasn’t ‘me.’ So when I came back to Morocco, I didn’t have a plan. It just felt good to be back, and it wasn’t a hard decision at all. I moved with my family, I was with my mum, with my grandma, and every day, I was reconnecting with my roots.”

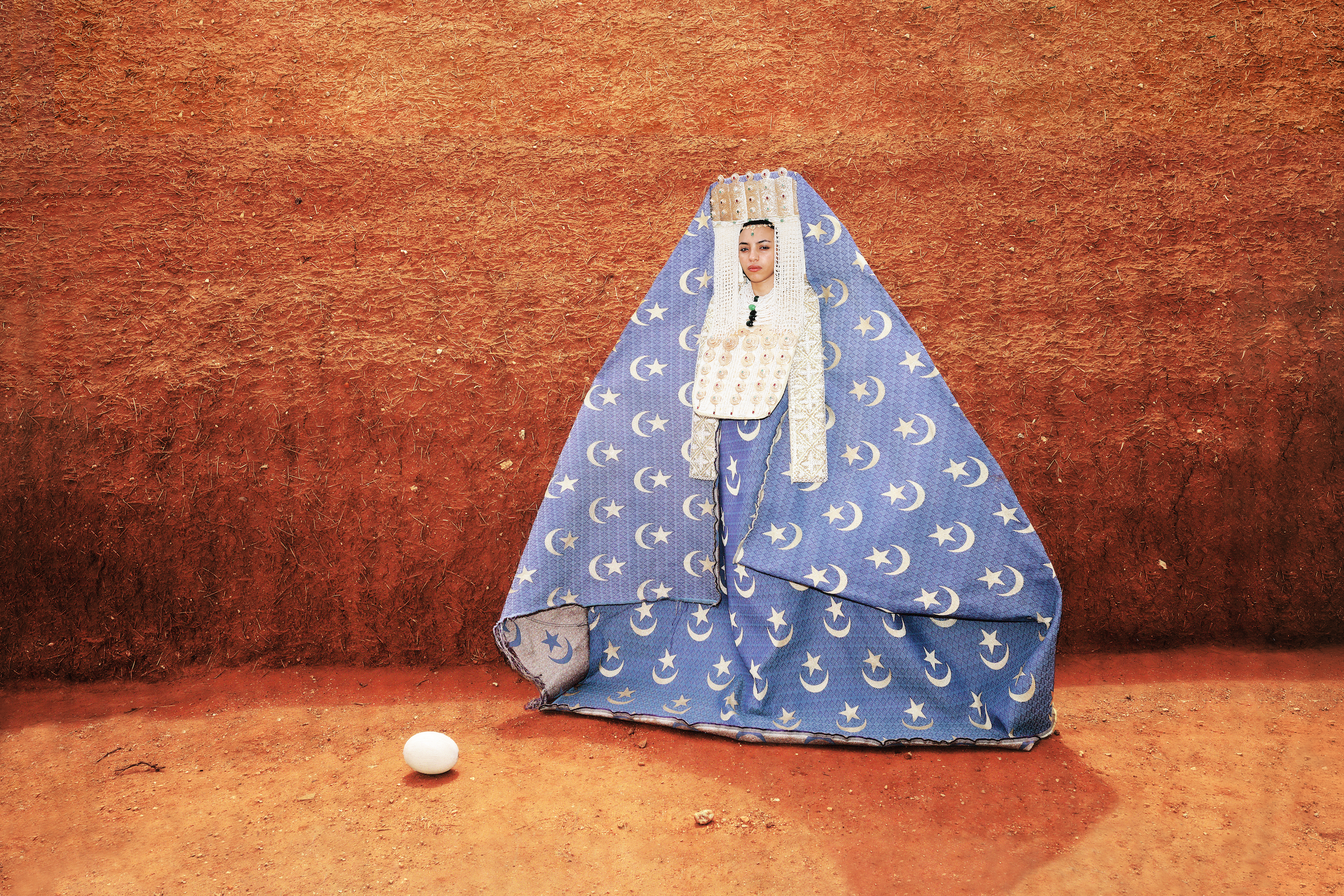

Dry Land reflects on her experiences growing up in Morocco, where femininity often felt like something to conceal rather than embrace. At the heart of the series is the labsa lakbira, a traditional bridal gown tied to memories of brides fainting under its weight. The fifth of seven dresses a Moroccan bride typically wears for her wedding, the gown is both beautiful and heavy – physically weighing over 20 kilograms. The dress Benabdallah shot was made from fabric sourced from Fes and she worked with a Neggaffa to help dress the model with proper jewellery. For Benabdallah, the garment is a powerful symbol of the weight of societal expectations placed on women. Yet Benabdallah’s work transcends heaviness – her subjects stand tall despite the heavy dress, embodying the strength of femininity and complicating notions of womanhood in Morocco.

“I like to call Morocco the country of contrasts,” Benabdallah says. “When I was in America, I had conversations with people – specifically Midwesterners – about how they saw Morocco or Muslim countries in general, and so much of it was untrue. Of course, Morocco isn’t perfect; there’s a lot of progress needed when it comes to rights and equality,” says Benabdallah. For example, young girls still struggle to access education in rural areas. “Morocco is a small country, but it’s so diverse and there are so many things that contrast each other. For example, the culture of Arabs and Amazigh, who are the natives, is completely different. What I found is that in more Arab families, it can be a little more sexist, whereas in Amazigh villages and rural areas, it’s much more matriarchal rather than patriarchal.”

Benabdallah recounts a post-earthquake experience in Morocco’s mountainous regions that left a lasting impression After the 2023 events left 2,900 dead and more than 5,500 injured, many were left homeless after their homes were destroyed, and Benabdallah accompanied a friend who was rebuilding eco-homes for affected communities. During meetings with the Amazigh villagers, the men stood up and left, saying, “If you’re going to ask questions about how you want the home layouts to be, just ask the women – they’re the ones who are always here.” Reflecting on this, she notes how starkly it contrasted with her own upbringing amongst Arab communities who are traditionally more patriarchal. “I’m not Amazigh, I’m more Arab, and I know for a fact that where I come from, that would never happen. It’s really interesting because there’s such contrast, and you cannot define Morocco by one thing.”

Before embracing photography, Benabdallah’s creative roots were in filmmaking – a medium she found both captivating and overwhelming. “It’s so intricate, so many departments and people are involved, so it’s much more complicated to tell a story in film than in photo,” she explains. Searching for clarity and a more direct form of expression, she began to question her approach. “I thought that maybe the next step to figuring out my voice is to do something more simple. Maybe photography might be the way to figure it out.”

While she might consider it as chance, Benabdallah’s journey into photography feels both intuitive and inevitable. Her cinematic background shines through in the whimsical, stylised imagery of works like Sacred Tree and No.5, drawing on a fantastical surrealism reminiscent of Arab fantasia. Whether intentional or subconscious, this approach softens the weight of heavier conversations, drawing viewers into her narrative with ease. These pieces, with their vibrant colours and dreamlike qualities, echo Morocco’s inherently rich and lively aesthetic.

This subtle sensitivity to storytelling extends beyond her imagery and into her creative process. At her 1-54 debut in Marrakech this February, which also featured works from her Al-Astrulabiya series, Benabdallah’s focus on collaboration with Moroccan artisans distinguished her work. This series explores ideas of cosmology and astrology which are cornerstones of the Islamic faith, and takes its name from a Syrian female astronomer. Rather than opting for industrially produced frames, she worked closely with local craftsmen to design pieces. “Seeing how craftsmanship is slowly dying, and bringing that back and into 1-54 was also a really incredible feeling, because it’s something that’s beyond me or my work,” reflects Benabdallah. “I took the opportunity that I had and didn’t just use some random frames that were made by machines. I actually worked with artisans that I grew up with, that I’ve always known. It was just the best feeling.”

Her dedication to bridging the past and present highlights the deeply personal significance of Benabdallah’s work. Her debut at 1-54 in Marrakech was not only a professional milestone but a moment of profound validation, both as an artist and as a woman navigating the expectations of her culture and family. “Exhibiting at 1-54, which is such a cool fair in the La Mamounia Hotel in Marrakech, with other artists who were incredibly huge, and bringing my family there, all of this really changed my whole life,” shares Benabdallah. “When you’re a woman, an artist in a family, especially an Arab family, you’re not really taken seriously. I always felt like I had to prove myself to every family member. I’ll always remember the opening day at 1-54 because it completely changed how every member of my family looked at me. It’s cheesy to say, but I think 1-54 really made so much more possible for me.”