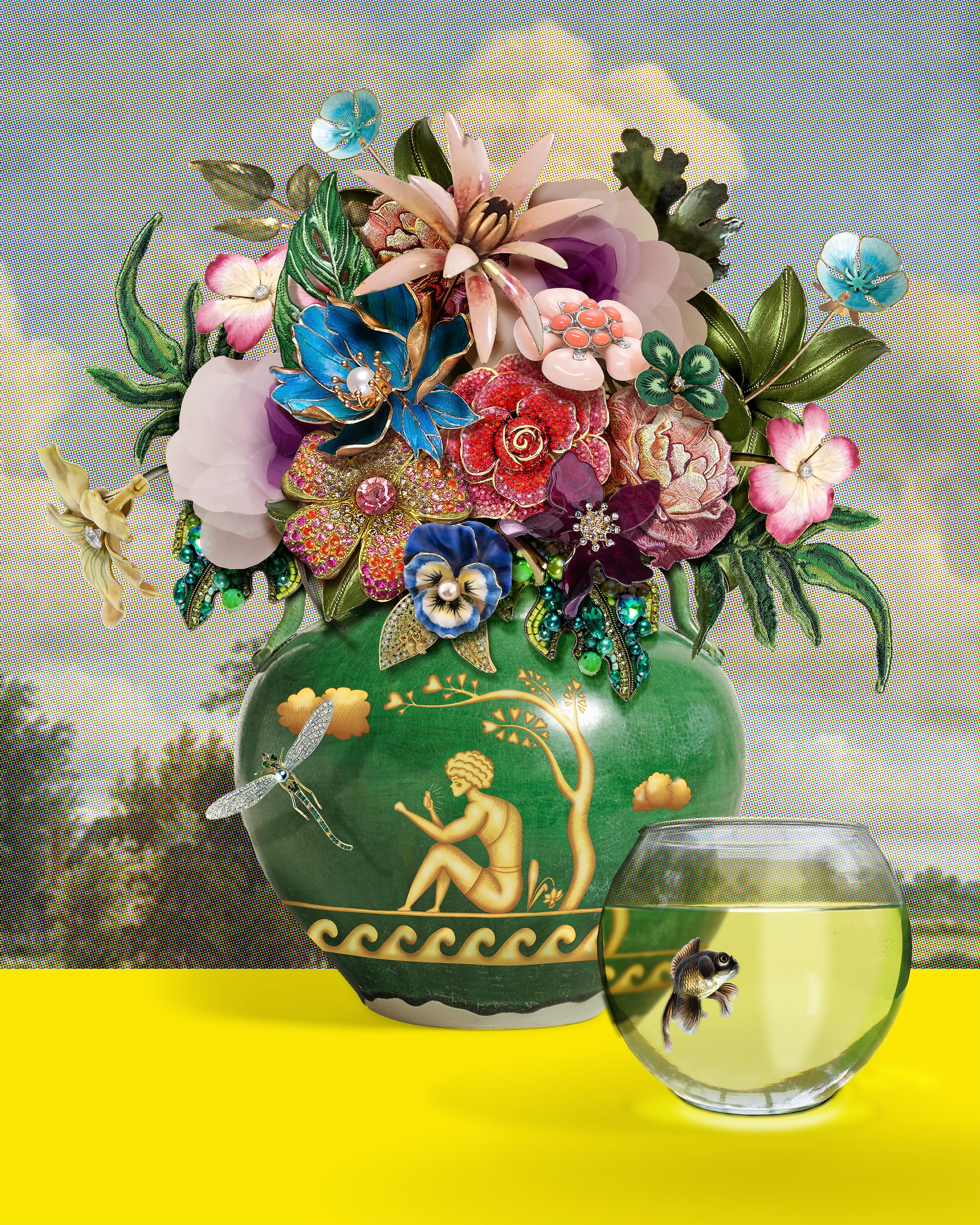

© Ron Norsworthy

The American artist tells Sarah Moroz about his latest show I, Narcissus, an exploration of self-love, at Houk Gallery

“Why is it bad to fall in love with yourself?” wonders Ron Norsworthy. “Why is it bad to find beauty within yourself?” It is this line of questioning that led the American artist to contemplate the nuance between what is it to see and what is it to recognise. “They are two different things – it’s like hearing and listening,” he reasons, speaking over a Zoom call from New York.

His magnetic, glamorous series I, Narcissus – encompassing 11 works (all made in 2024) on view through 21 December at Edwynn Houk Gallery – spotlights the queer Black male figure recast within the framework of the Ancient Greek myth of Narcissus. The original myth consequently punishes such vanity, but Norsworthy makes the central lesson about championing visibility and finding salvation. Here, Narcissus provides a trope that empowers queer Black men through unrepentant self-love, instead of valorising the ne plus ultra of white male exceptionalism.

His collaged relief work is created by collecting photographic fragments and re-photographing existing media (freeze-framing a film; scanning photos from an album). He re-contextualises these components into a digital collage, placing each upon wooden substrates so the work becomes dimensional. Given his background as a production designer, “there’s very much a mise-en-scène feeling, or the idea that you’re looking at a set,” Norsworthy notes. His distinguished visual vocabulary recurs throughout the images – doors, windows, mirrors, light fixtures – all suggest portals, exploration, pathways into other worlds, the potential for discovery.

“I just lived in TV shows. I found my escape as a little Black, gay kid – my world was boring compared to these worlds”

He toys with perspective as one would with a photographic lens or unusual angle, just as “a camera can skew perspective in all sorts of ways.” Norsworthy explains: “If you look closely at the rooms, the architecture doesn’t exactly work. That is very intentional… it is suggesting a kind of tension. Everything is a little precarious.” Explicitly mixing the familiar with the strange, the mirrors especially are laden with uncanny symbolism: “When you look in the mirror, society mediates your upbringing, your journey, what looks back at you. We think it’s us, but really our idea of what we want to be is what society expects us to be.”

A self-professed “art geek,” Norsworthy deliberately sprinkles in art historical easter eggs – although he qualifies that “sometimes they’re not easter eggs: sometimes they’re, like, giant in-your-face things”. It’s his way of acknowledging that an artist’s output is influenced by an existing creative lineage. One work, named after a 16th-century painting by Parmigianino, Self Portrait in a Convex Mirror, puts a fresh spin on today’s selfie culture while engaging with the timeless theme of self-perception. “I’m having a conversation with the art canon and how complicated that can be for me, as a queer Black artist,” Norsworthy states. He also nestles existing works by Black artists who straddled the 19th and 20th century – painters Aaron Douglas, Laura Wheeler Waring, and Charles Ethan Porter – within his own collages “to be in dialogue with some of the predecessors that came before me.”

As for a more contemporary conversation about Black visibility and representation – themes readily celebrated by a young generation of photographers in The New Black Vanguard – the topic is one he discusses cautiously. “I think in white, patriarchal, capitalist structure, with any identity that’s not that, there’s the potential to be flattened. My work wants to push back against the expectation of what this dominant social structure expects me to be about.” The concept of Black excellence and Black joy “doesn’t look one particular way… I don’t think that that’s describable through one lens.”

Having said that, he adds: “I don’t want to do anything that even resembles trauma, or that is a performance of pain, or that fixes these reductive ideas of Black oppression. All of the figures in this work are in repose; they’re in deep thought or reflection. It’s intimate.” Norsworthy speaks directly to Black communities and emphasises that they can form their own aesthetic conceptions even when excluded from mass culture: “We can all locate our own personal beauty and create our own narcissist experiences.”

Amplifying that beauty in full effect, the silhouettes within Norsworthy’s collages are supremely stylish, sporting knotted foulards, jumbo broaches, crisp suiting. That luxe vibe was inspired by TV shows Norsworthy watched growing up that featured outsized style, namely Soul Train, Dynasty and Dallas. The sense of the cinematic, of the exaggerated, never left him. “I just lived in TV shows. I found my escape as a little Black, gay kid – my world was boring compared to these worlds. I wanted to live in these plots.” He extrapolates: “I’m playing with the idea of physical beauty, but there’s also the things that we do… to help us be seen by others as beautiful.”

The accessories and garments form particularly compelling ensembles because they stem from varied sources. “There’s an anachronistic element in my work. There’s one piece where the figure has no shirt on” – that would be Regarding Narcissus – “wearing a beautiful turquoise necklace and a flower in his hair. I cut it out of a portrait of Billie Holiday; the necklace is some estate jewelry piece. The pants are from a 1940s photograph, a rather famous one.”

He notes: “I love fashion, but obviously how do I receive fashion? It’s through photography. That’s why it’s my medium of choice. I’m trained as a painter, but painting didn’t do it for me. Photography does it for me.”