© Sakir Khader

The photographer’s meteoric success is a testament to the stark reality of life on the ground in Jenin refugee camp. In this feature, Khader explains why he photographs the dead, bites back at accusations of ‘terrorism’ in his work, and discusses his upcoming monograph and debut solo show at Foam, exploring the role of the grieving mother in Palestine

When Sakir Khader shares his screen with me, he opens the PDF of his latest book, Dying to Exist, and shows me the first few pages. They feature tender, archival baby photographs, placed individually on each page with plenty of white space, which calls us to meditate on each image for a moment. “These are photos of my friends [as babies] who got killed in the Jenin refugee camp,” he tells me.

Netherlands-based Khader began documenting his homeland of Palestine in 2021 as part of his documentary filmmaking-career, which has also taken him to Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria. His real first experience of photographing was in Syria in 2018-19 using a “cheap point-and-shoot 35mm camera.” And later in Iraq in 2019 with his first professional camera, shooting behind-the-scenes as part of his documentary series The Ruins of Iraq, about the aftermath of the battle against ISIS. In 2021, he started photographing in Beita – his grandmother’s village – during the uprising of Sheikh Jarrah in Palestine, making shots which launched him into the world of imake-making. Though he’s not been taking photographs for long, Khader has already amassed awards, interviews, a loyal following, and, in 2024, a place at Magnum as the agency’s first Palestinian nominee.

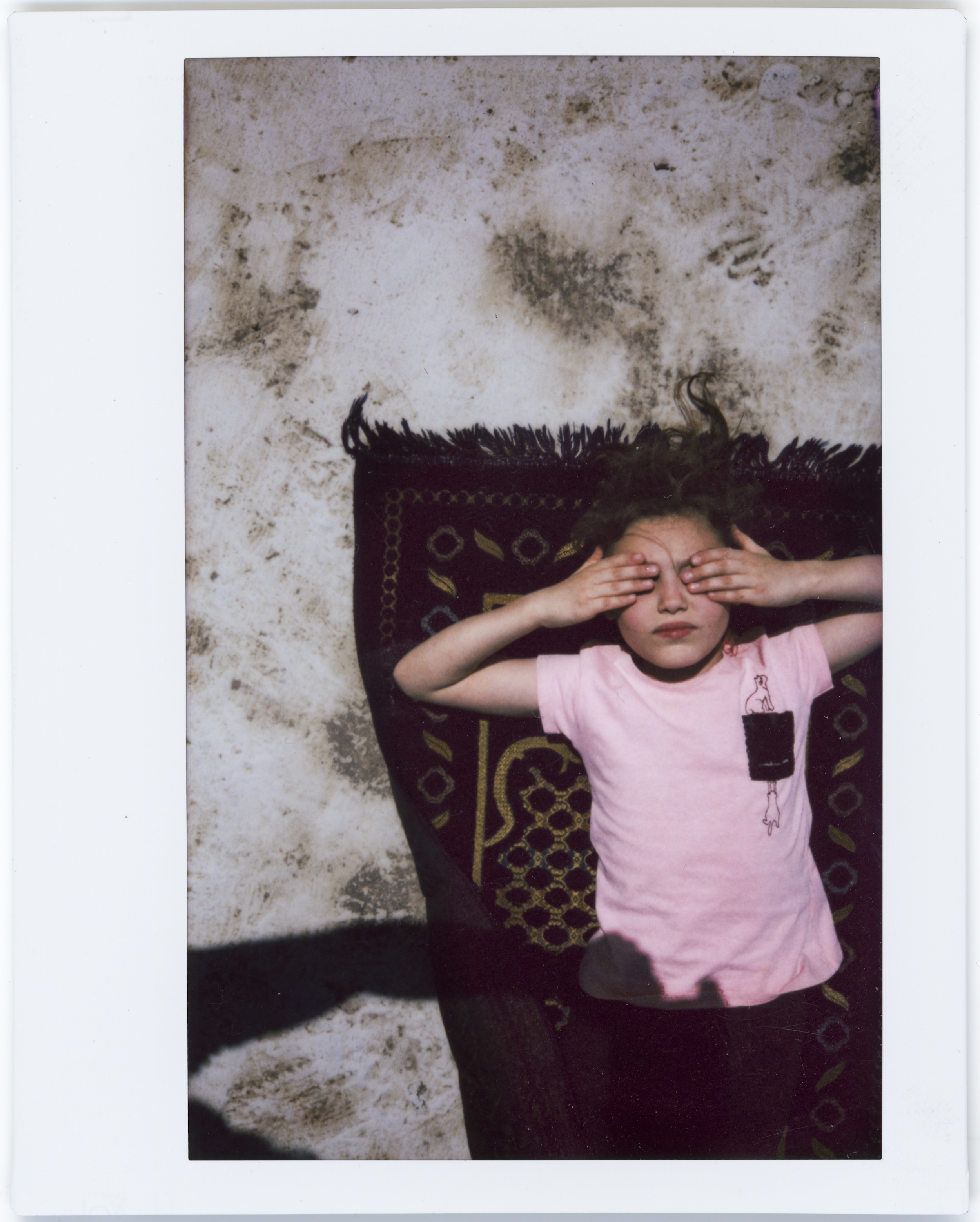

Dying to Exist is not an easy book, but it depicts a reality for many Palestinians and, therefore, is a necessity. The first image taken by Khader in it shows Amjad Al Fayed, who he photographed as a young child in 2019. The boy was killed in 2022. “I promised him that I would come back and make a film about [him], but I never fulfilled the promise,” Khader recollects. After Al Fayed’s death, Khader became curious about what would have been, had he had the chance to become a man, “What would have become of him, and what’s the environment he would have grown up in?”

Israel’s war in Gaza has been described by journalists and aid workers as “a war on children” because of the strip’s high population of under 18-year-olds – and that sentiment applies to the whole of Palestine. Khader’s book couldn’t be clearer evidence. The next image is a photograph of Al Fayed’s grave, the child’s face on his tombstone. The book then elaborates from this starting point, and depicts life in Jenin refugee camp.

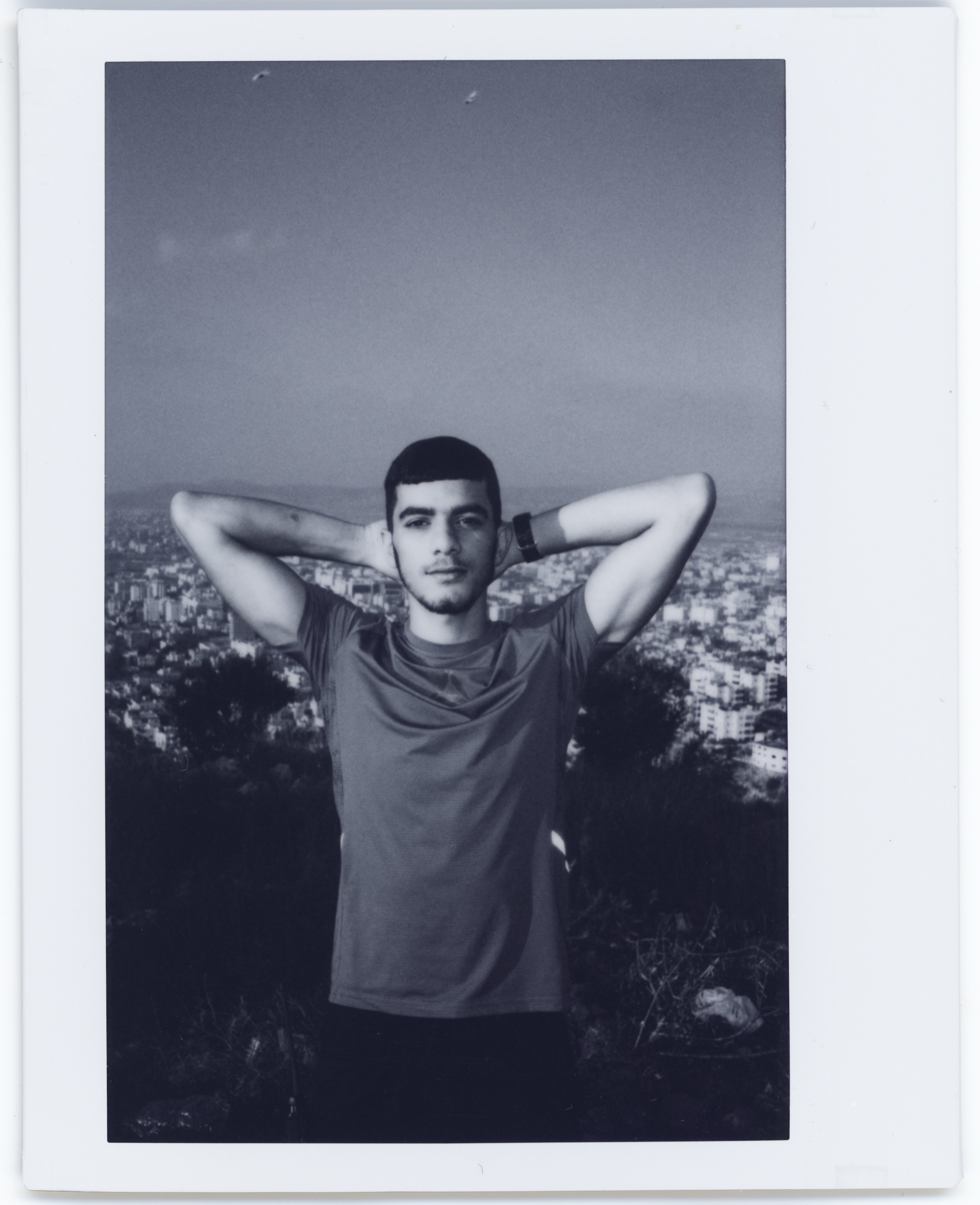

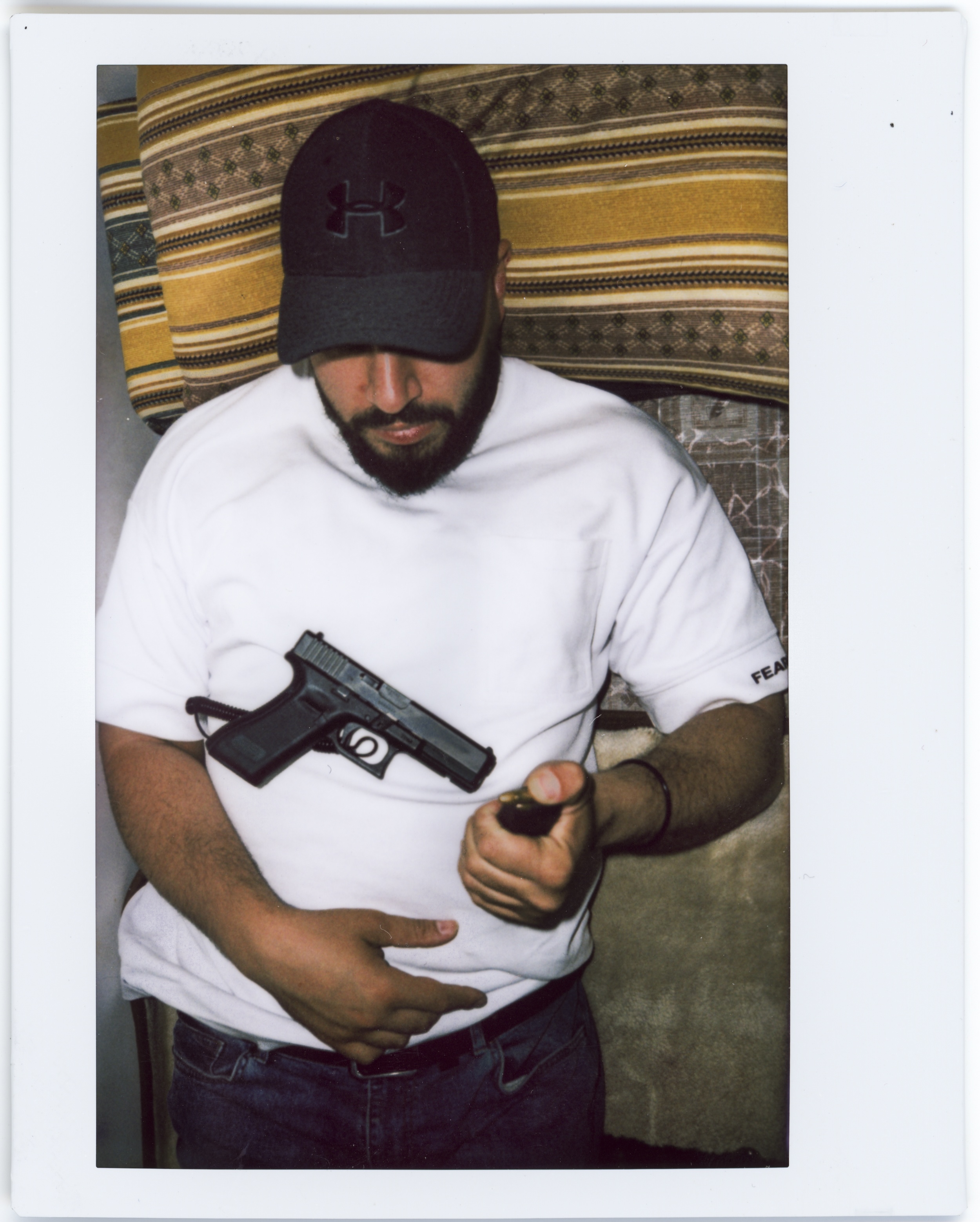

In another scene, Khader takes a considered and poetic portrait of a young man smiling at the camera – Yassine Ahmad al-‘Areidi, whose face is close to the lens and whose body is turning to us, in a welcoming gesture that beckons us closer still. The next images are of the same man three days later, his body is lifeless and his face bearing blood instead of a smile. Many of the boys and men photographed in the book are shaheeds – martyrs – a term which has been conflated with ‘terrorism’ by many media stories. In fact, the violence present in so many of Khader’s images has become a point of controversy for some, who see his photography as endorsing aggression. His practice thus begs the question of what the industry deems permissible to photograph and disseminate en masse.

Khader attempted to travel to the US in 2020 and, on being denied entry, discovered he had been placed on a terror watch list. He’s also been arrested several times in Turkey and deported back to the Netherlands, “for being who I am”, he tells me. “And I still don’t know the reason why I am on this list. For me, being a Palestinian, being a brown man, being a Muslim, they don’t need a reason.” Khader chose to keep this private for years, out of fear for his safety – but now, he wrote in an Instagram post in summer 2024, “refuse[s] to stay silent any longer, because silence means surrender”.

“Over the past years, I’ve been regularly imprisoned, beaten, inhumanely interrogated for long hours, deported, forced to unlock my phone, taken by intelligence agencies, and banned from several countries while always hearing the same accusation: terrorism,” he continued. “And if this isn’t disturbing enough, I recently found out my name is on the United States terror watch list […] We will fight this in court, and my name will be taken off the list. I’m speaking out and fighting back, because if something were to happen to me, I don’t want this unjust label to be used as a justification.”

“Before Magnum, when I wanted to get things done, it was really hard to get industries to believe in me or give me an exhibition. But since joining Magnum, I honestly have a privilege. And I can offer Magnum an important perspective which doesn’t only see the world from a Western lens”

Since receiving his Magnum status – after a suggestion from fellow Magnum photographer Myriam Boulos – Khader hopes being with the agency will grant him more leeway to travel, aiding his reputation as a legitimate photographer rather than an ‘amateur’ photographer. “I’m very happy to be with Magnum as it gives me a protective status,” he tells me. “When I cross borders, I’m not just a guy with a camera. Before Magnum, when [I wanted] to get things done, it was really hard to get industries to believe in me or give me an exhibition.” Now, he says the recognition offers him a level of privilege. And he hopes that, as the agency’s first Palestinian photographer, he can offer Magnum something new too, “an important perspective which doesn’t only see the world from a Western lens.”

Even so, no agency can protect Khader from “Israeli bombs,” he tells me, reminding me of the death of Shireen Abu Akleh, killed by Israeli forces whilst in her press vest and covering a raid on the Jenin refugee camp in 2022. Since 07 October, 137 journalists and media workers have been killed in Gaza, making the war the deadliest conflict for journalists that the Committee to Protect Journalists has seen. Of the dead, 129 were Palestinian, two were Israeli, and six were Lebanese.

“I was for a long time scared of [getting] cancelled,” Khader tells me of the content of his images, “because once you’re outspoken in the Netherlands and they start to chase you, you really get in trouble. But why should I be scared of these people [who] claim you’re a terrorist for just showcasing Israeli war crimes?” The outpouring of support, both professional and by fans of his work, has encouraged Khader to remain outspoken against the double-standard treatment he receives from authorities and the media.

And so, Dying to Exist is a fitting title for a project whose claim becomes increasingly apparent, by a photographer who is struggling simply to be in a world in which the odds are stacked against him. The book had its official launch at Offprint during Paris Photo on 07 November and now Khader is looking forward to his debut solo show at Foam in February, Yawm al-firak, covering themes of loss, motherhood and martyrdom. “It’s about mothers saying farewell to their martyred sons. I don’t think I would have gotten that exhibition before Magnum,” Khader muses.

“Losing your son in a car accident is as painful as losing them by war. Losing your son is losing your son”

Khader is often inundated with messages asking why more women don’t feature in his images. But for many Muslim women who wear the headscarf, being photographed is uncomfortable or simply disrespectful. As a man, Khader tells me, he cannot “wander around and just photograph women. Why are people obsessed with our women?” However, this project does focus specifically on the pain of women and mothers. “Losing your son in a car accident is as painful as losing them by war. Losing your son is losing your son,” he claims, hoping the project speaks of the universal pain of grief. One image shows two women in a desperate embrace, their faces contorted by a wailing you can almost hear. Another frame, shot from above, shows many women wearing different expressions of the same sorrow.

After winning The Silver Camera in 2023 for his photo series The Life on the West Bank before 7 October, Khader’s work was exhibited at the Museum Hilversum in spring 2024. It is the most prestigious prize for documentary photographers in the Netherlands, and he had previously won it in 2022, for his photograph of an 11-year-old Afghan boy selling his kidney to feed his family. He was then invited to participate in Breda Photo Festival in autumn 2024, with an exhibition titled I Have No More Earth to Lose, curated by Mohamed Somji. The title takes its name from the Mahmoud Darwish poem A State of Siege, in which he writes: “Here, Adam remembers the clay of which he was born / He says, on the verge of death, he says, / “I have no more earth to lose” / Free am I, close to my ultimate freedom, I hold my fortune in my own hands / In a few moments, I will begin my life / born free of father and mother.”

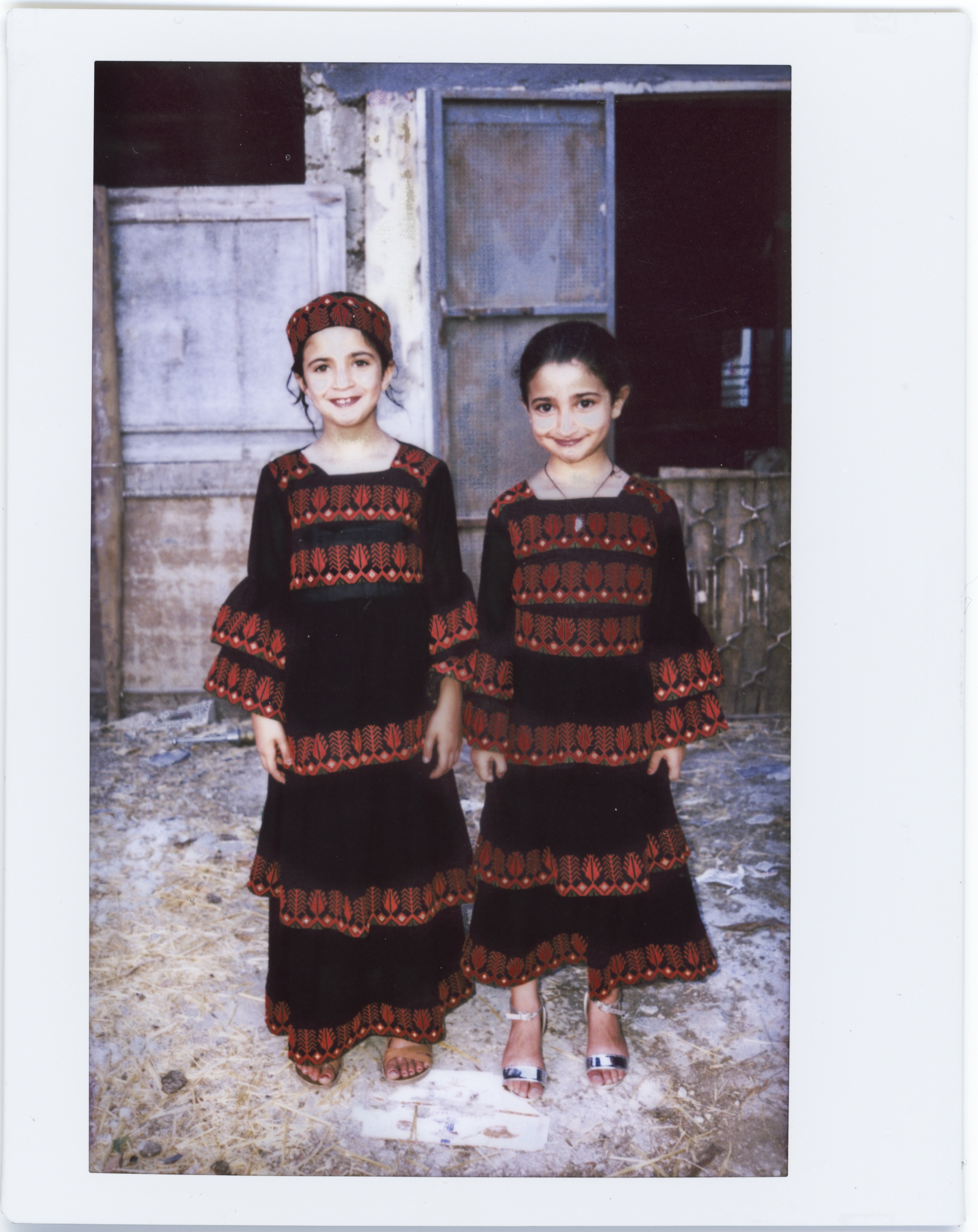

Khader’s Breda exhibition, where I saw his work exhibited for the first time, was immediate, sobering, and a contrast to his upcoming work at Foam. For here, we were presented with a story that was also colourful and hopeful. Curator Somji advised Khader to vary the exhibition, the photographer says, that if he wanted to “tell people a story that is really touching, you cannot show people only weapons. You cannot show them only dead bodies at funerals”. “At the end of the day, we are living on the land in Palestine,” Khader adds. “And of course, you have a bit of violence, a bit of grief, because that’s the reality. But at the end of the day, I wanted to show who we are as Palestinians. We are not just victims. We are people living in our dignity, and that’s what we want, and that’s what we’re fighting for.”

“When you eat from the same plate, you sit around the same table, you sleep in the same room, and the next day, suddenly, that person is killed, it’s as if a part of you got taken away. And every time someone gets killed, even if it’s a kid in Gaza I don’t know, it’s already a part of me, because it’s a part of my homeland”

In one scene we see a lady dressed in traditional tatreez, standing in a lush grove with an olive tree, a symbol of Palestinian resistance, in the background. She is glowing, Khader’s high flash bringing out the white of her dress so she looks angelic, eyes gazing upwards and headscarf flowing in the wind. The image is complemented in the exhibition by a parallel image, depicting a scene where a divine light is shining through a large tree, reminiscent of the story of Abraham receiving the image of God in the form of angels under an oak tree in Mamre (now Hebron, West Bank, Palestine).

Khader’s images are immediately recognisable, he’s got his style nailed down. His portraits are his most striking medium. One image from his Breda show presents a young boy looking back at us, with an expression far wiser than his years; he’s Mohammed Amjad al-Jo’os, and is ten years old. A sniper killed his brother, who was then crushed under an army truck. Khader is a master of shadows, the blacks are dark and the whites are bright under his heavy contrast. And we’re very close to al-Jo’os, as we are with many of his portrait subjects: the Palestinian-Dutch photographer has never photographed with zoom lenses. “I want to be close to the people to feel really in their inner circle, instead of being an outsider, photographing from a distance,” he tells me.

“Sometimes I just buy a very experimental cheap camera. The colour ones are shot on a 20 Euro camera,” Khader adds, of some of his colour shots from the exhibition. One scene shows a family of six children and a father in saturated reds and blues. The setup is almost theatrical, Khader making full use of the frame with two girls downstage left, two girls downstage right in their traditional dresses, one boy far upstage, and the last boy sitting centre on a well-behaved sheep. “If you look at your whole life through the same viewfinder, your whole life will look the same,” Khader explains to me. “I have my main cameras that are monochrome. They don’t shoot colour, but I also use Polaroid and I shoot 6×6. I try different things so I can keep looking differently at my own people and the region.”

Photographing so much death, it’s difficult for Khader to be detached from those he documents. He spends significant amounts of time with his subjects, forming bonds with them. “We survived everything together,” he tells me. “When people open up their house for you and guarantee your safety and feed you, when you eat from the same plate, you sit around the same table, you sleep in the same room, and the next day, suddenly, that person is killed, it’s as if a part of you got taken away. And every time someone gets killed, even if it’s a kid in Gaza I don’t know, it’s already a part of me, because it’s a part of my homeland.”

Sometimes, in fact, Khader is so affected by witnessing death that he chooses to “photograph with [his] eyes”. It’s testament to the emotional toll of his work, he tells me; “I find it important to look at that person with my eyes, not with my camera.”

Dying to Exist is available at 550bc.com

Yawm al-firak will open at Foam Gallery, Amsterdam, 07 February – 14 May 2025