All images Not What You Saw © Keerthana Kunnath

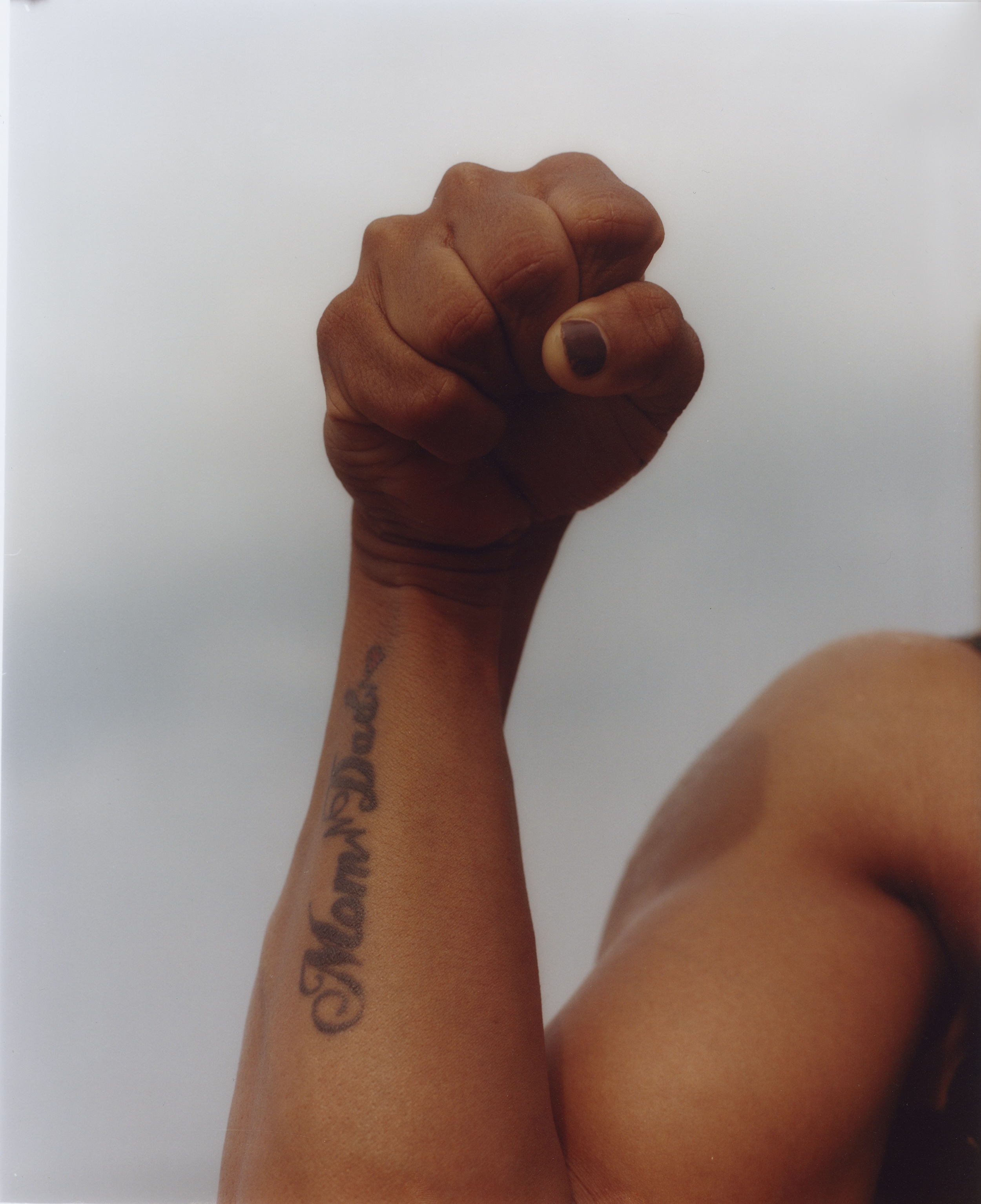

Keerthana Kunnath reveals how a community of South Indian bodybuilders dismantle longstanding perceptions of femininity and body image

Earlier this year, Keerthana Kunnath was researching female Kalari artists – an Indian martial art that originated in Kerala during the 11th century CE – when she stumbled upon 30-year-old female bodybuilder Arathy Krishna. “In awe of her physique as well as her grace”, Kunnath decided to pull on the thread and uncovered a world of female bodybuilders in the region, providing the basis for her project Not What You Saw. Drawn to unconventional femininity, the London-based South Indian photographer sought to highlight the group’s stories as a challenge to the gender status quo in India, where women are encouraged to follow rigid stereotypes of domesticity and idealised beauty.

As a “brown queer woman”, Kunnath is drawn to narratives that challenge conventional gender roles. “In the cultural landscape from which I originate”, the photographer tells me, “muscular women, exuding confidence and strength, are a rarity. While we often encounter women in roles such as doctors, nurses, teachers, or the occasional police officers, the presence of a female bodybuilder is unprecedented”.

“It’s a complex landscape of stereotypical ideas and societal expectations of femininity [the bodybuilders] have to navigate.”

After hours of research, Kunnath found other female bodybuilders and says she connected with her subjects on being “the black sheep of the family… and wanted to challenge the notion of what a woman can be”. The bodybuilders had never been photographed, let alone by another woman, so were keen rather than hesitant to take part in the project, especially given the potential to inspire other women to take part in the sport.

In India, where the femicide rate is among the highest in the world, dismantling pre-existing, harmful attitudes towards women is an imperative for photographers like Kunnath. In Southern India, as with many other communities around the world, women are pressured to conform to traditional beauty standards: a lighter complexion, slim build and long hair are preferable features. There is also a strong emphasis on being a suitable candidate for marriage and appeasing the male gaze. “These bodybuilders on the contrary focus on their muscles and strength, which often defies the conventional views on femininity,” Kunnath explains. “It’s a complex landscape of stereotypical ideas and societal expectations of femininity they have to navigate.”

Due to the use of steroids – which often deepen the voice – the participation in gym spaces, and the transformation towards a more built, typically ‘masculine’ physique, many of the women in Kunnath’s series did not have their family’s approval to pursue bodybuilding. Many kept their practice a secret, but Kunnath says, “one of the girls told me that her family had finally come on board with her interest in bodybuilding after seeing her hard work and passion towards the sport.” Nevertheless, the family received pressure from relatives, who were worried the bodybuilder “wouldn’t find a prospective groom”.

The athletes in Not What You Saw are multifaceted – they are also mothers, designers, sales women and teachers. Chitra, for example, is a 23-year-old who works as both a language teacher in her local school and a personal trainer in order to support herself and her family. Another unnamed bodybuilder has moved away from her hometown and keeps the sport a secret in case she is refused a rental apartment as a female bodybuilder. “It really reminded me that as women, we have to face so many more hurdles to do the same job or sport as men,” Kunnath says of making the work. The process dismantled the photographer’s own preconceptions, she says, and she was surprised to learn that physical strength and muscularity can coexist with femininity and womanhood.

Women’s participation in typically masculine or male-dominated sports is a contentious topic – perhaps now more than ever. This month, spectators of the Olympic Games in Paris saw Algerian boxer Imane Khelif experience harassment and bullying from pundits – after beating her Italian opponent – who falsely claimed Khelif was a transgender woman and called for her disqualification due to her high levels of testosterone and her physique. The uproar fuelled a wider discussion around the common trend for racialised athletes who do not fit the popular image of femininity. And prior to her disqualification at this year’s Olymic Games, Indian wrestler Vinesh Phogat led a sit-in protest alongside Bajrang Punia and Sakshi Malik against the WFI chief, Brij Bhushan, for alleged sexual harassment in New Delhi last year, but the athlete was detained by police.

Kunnath says the discrimination Khelif and Phogat faced are indicative of the challenges “a lot of POC women go through on an everyday basis”. In the future, Kunnath hopes to explore the personal lives of her subjects in order to highlight their daily lives and the challenges they face. “I believe by showcasing their experiences with those of their mothers and other female friends and relatives, this project can question the traditional role of men as providers and protectors,” expands Kunnath.