Ryszard Kisiel, 1985-1986, Queer Archives Institute collection. All images courtesy the artists

Visitors are treated to a breadth of approaches, from Polish subculture archives to intimate domestic imagery

Edinburgh Art Festival returns for its 20th birthday this month, “tracing lines through personal histories, the natural world, postcolonial landscapes, and the global political stage,” director Kim McAleese says. Photography fans should head straight for Home: Ukrainian Photography, UK Words at Stills Centre for Photography; Karol Radziszewski’s Filo presentation at City Art Centre; and Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970–1990, which is touring from Tate Britain and features the same remarkable archival imagery from the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, Format Collective, and many more (at Modern Two until 26 January 2025). Also look out for Ibrahim Mahama’s photographs of Ghanaian communities pushing rusted train carriages in lateral series along the walls of Fruitmarket, and Flannery O’Kafka’s intimate domestic capsule at Sierra Metro, in which the artist combines disarming family portraiture with superimposed prints featuring diagrams from old North American colonial communication manuals.

Ukraine beyond the front pages

To coincide with the Eurovision Song Contest 2023, Liverpool’s Open Eye Gallery invited curators from the UK and Europe to select projects by Ukrainian photographers and contribute texts for Home: Ukrainian Photography, UK Words. The resulting exhibition featured 15 photographers, including five specially commissioned bodies of work paired with responses by five UK poets exploring shifting notions of ‘home’ during wartime. Home has now been updated and is on show at Stills in the heart of Edinburgh’s Old Town. Curated by Viktoria Bavykina and Max Gorbatskyi, the exhibition presents the work of Igor Chekachkov, Alexander Chekmenev, Nazar Furyk, Mykhaylo Palinchak, Polina Polikarpova, Andriy Rachinskiy, Elena Subach and Daria Svertilova.

Home showcases the breadth of photographic responses to the war – and crucially, a conscious curatorial move away from photojournalism to reflect a new complexity of response. “We wanted to offer alternative imagery from what people see in the media,” Gorbatskyi tells me, picking out the work of Elena Subach and Nazar Furyk, whose photographs are allusive and (mostly) subjectless, focusing on the remnants of the war rather than its visual excesses.

Both artists worked as volunteers, giving them access to civilians at particularly vulnerable moments: Subach on the Ukraine-Slovakia border; Furyk in Kherson after travelling from Kyiv when the full-scale Russian invasion began in February 2022. Subach depicts the chairs – displaced people’s “temporary havens”, as Gorbatskyi describes them – which served as resting points before people crossed the border. Blankets, coats and gloves are remnants of previous journeys which people have left behind out of either necessity or generosity. Furyk’s series is similarly poetic, showing momentarily quiet side streets and drying clothes in the city which was recaptured by Ukrainian forces in November 2022.

Furyk is one of several photographers in the show who has adapted their style since the full-scale invasion, embracing a more documentary format. Mykhaylo Palinchak worked as the official photographer for the president of Ukraine from 2014 to 2019 and then shot commercially, but since the war began has been visiting liberated towns around Kyiv, documenting the destruction caused by Russian shelling. “His photographs were everywhere and really helped change the public opinion on the war… he was looking at the burials, the excavation,” Gorbatskyi points out. To fit the ethos of Home, the curator made a lighter selection of Palinchak’s images, avoiding the most graphic images in favour of more socially rooted urban work. “We tried to avoid the journalistic approach in the show, while still acknowledging that it has some power,” Gorbatskyi reflects.

Igor Chekachkov travelled from Kharkiv to Lviv when the war began, making photographs of those who have also been relocated within Ukraine. “He redefined his previous series and started to photograph the daily lives of the displaced,” Gorbatskyi says. One image shows young people making Molotov cocktails, even though they are miles from the current conflict zone, demonstrating the uncertainty that has swept the country. Chekachkov now photographs displaced Ukrainians in each place where Home travels, a continuous evolution which generates new, localised material for each audience base, so far in Liverpool, Edinburgh, Chester and Salford.

The inclusion of Alexander Chekmenev’s Passport series gives the show a historic dimension, placing the war in its post-Soviet context while nodding to the decades of smart image-making from the region. When Ukrainians had to apply for new documentation after independence in 1991, Chekmenev used the opportunity to highlight the living conditions for working-class citizens, making extra sets of pictures beyond the tight focus of the passport shoot. The photographs are an intimate time capsule, in stark contrast to the heroic portraiture of Chekmenev’s wartime Citizens series, which is hung adjacently (the photographer had photographed Volodymyr Zelensky for TIME magazine in December 2022). This pairing of two Chekmenev series proves that, although Home does feature elements of the heroic, the tragic and the mournful which we have come to associate with Ukrainian conflict photojournalism, these emotions never suffocate the complex personal stories which often predate the full-scale invasion itself – and which ultimately provide a deeper and more captivating survey of today’s reality: a protracted stalemate which is increasingly dependent on the will and internal politics of other nations.

Vignettes from the queer Polish underground

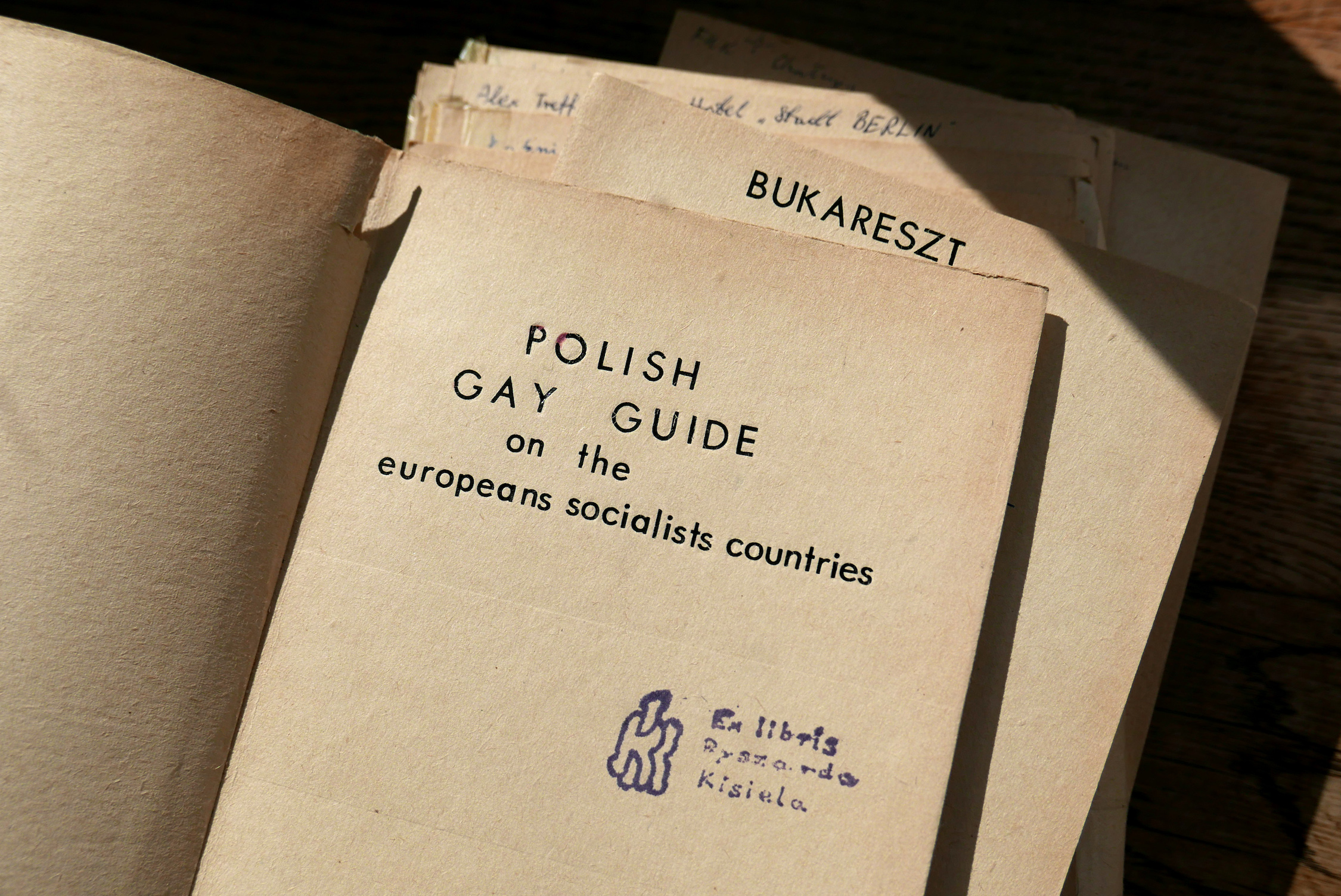

Karol Radziszewski brings Filo to City Art Centre for this year’s festival, following its presentation at Auto Italia in London. The installation of archival materials and the artist’s own paintings all stem from Radziszewski’s relationship with Ryszard Kisiel, founder of Filo, a late-1980s underground queer magazine run from the Polish underground. The magazine created a focal point – and physical legacy – for the country’s drag scene and Warsaw’s more visible gay communities, but also prompted a flurry of activity in the form of DIY photoshoots, written guides to cruising spots and mail into the publication. All are included in carefully arranged vitrines, which are just a small portion of Radziszewski’s wider research into queer communities in Eastern Europe, different iterations of which have been shown in Berlin and Prague.

The mission is to explore “queerness not just as a topic, but as a form”, Radziszewski tells me. The artist has been an important player in the Polish queer scene for 20 years; he was “the first (officially) openly gay artist in Poland when I made my 2005 show”, the same year he founded DIK Fagazine, a publication focusing on the country’s contemporary queer culture. Over the next few years he decided to look to the past, leading to his encounter with Kisiel in 2009, from which a close creative relationship formed. At the activist’s cluttered flat in Gdańsk, Kisiel began to share portions of his vast domestic archive of Filo materials and associated ephemera, which at that point he had not considered in an artistic context. “Even in the 1990s, these topics weren’t part of socially engaged art,” Radziszewski explains. He gradually convinced Kisiel to begin sharing his work for artistic means, leading to Kisieland, a film 2012 composed of slides of the drag scene stored under Kisiel’s bed.

The project centres on the trust between the two men, which is crucial given the anti-LGBTQ stigma which many people still experience in Poland (including within arts institutional contexts). This degree of secrecy informs the presentation, with Radziszewski pointing out that although Kisiel moved in a large and diverse community of drag performers, it is rare to see his peers photographed. Many of the archival images from the early years of Filo show Kisiel himself – portraits where, out of necessity, he becomes both subject and director. Intriguingly, Kisiel and other performers would never use the terminology of drag, Radziszewski explains, instead drawing on French cabaret as a reference point for their activities. The images retain a warming DIY quality: on occasion an untrained photographer would wait too long to capture the image and so accidentally shoot a couple having sex.

Filo generated a variety of responses which are also included in the exhibition. Underground cruising guides to various Eastern European locations speak to the extent of these hidden histories, while other publications include informal maps and tips for a community very much living outside of the mainstream. Also included are portfolios that the magazine’s audience was sending in: drawings, photographs from global queer communities, and messages of support to Warsaw. “It was a lot of exchange which involved a degree of risk,” Radziszewski says. The show is testament to the care and courage involved in maintaining these underground cultures – and to Kisiel’s diligence in keeping all the materials. (One vitrine shows hand-drawn design sketches for an early issue of Filo, untarnished and unfolded despite their age; another presents later editions of the magazine after Kisiel withdrew and the Filo name was changed). It is interesting to consider how ideas of explicitness have changed over time, and how the circulation of publications has morphed according to ideas of behavioural and cultural propriety.

Radziszewski is keen for his research to remain activist-based – that is, not operating exclusively within an artistic institutional framework. Troves of Kisiel’s written materials have now been donated to an activist LGBTQ group in Warsaw, rather than seeking collaboration from national museums. Radziszewski is beginning to digitise more of the visual archive, part of bringing the artefacts into a different sphere of meaning: many of the producers are amateurs or were working instinctively, rather than seeing themselves as artists. Timing and a growing acceptance of LGBTQ histories is changing that framing: “I was lucky that it was a moment where Poland was ready to learn within the avant-garde,” Radziszewski says of presenting Filo in his home country. “The reception was very good.” Both men are involved in an ongoing process of curatorial guardianship. “It’s crucial that artists, not academics, are doing this work,” Radziszewski concludes. “Academics analyse data and work in libraries, this project requires trust – going into Kisiel’s flat seven times in three years to find something.”

Both these festival exhibitions reaffirm the fact that photographic practice is context-dependent and protean – and that curators, commissioners and archivists have a significant role to play in packaging information for audiences. One style or focus can become steadily redundant in the face of new information or changing social attitudes; another can appear increasingly compelling, even necessary when an artist faces a new personal, social or, in the case of Ukrainian photographers, geopolitical reality.

Edinburgh Art Festival is at various venues across the city until 25 August