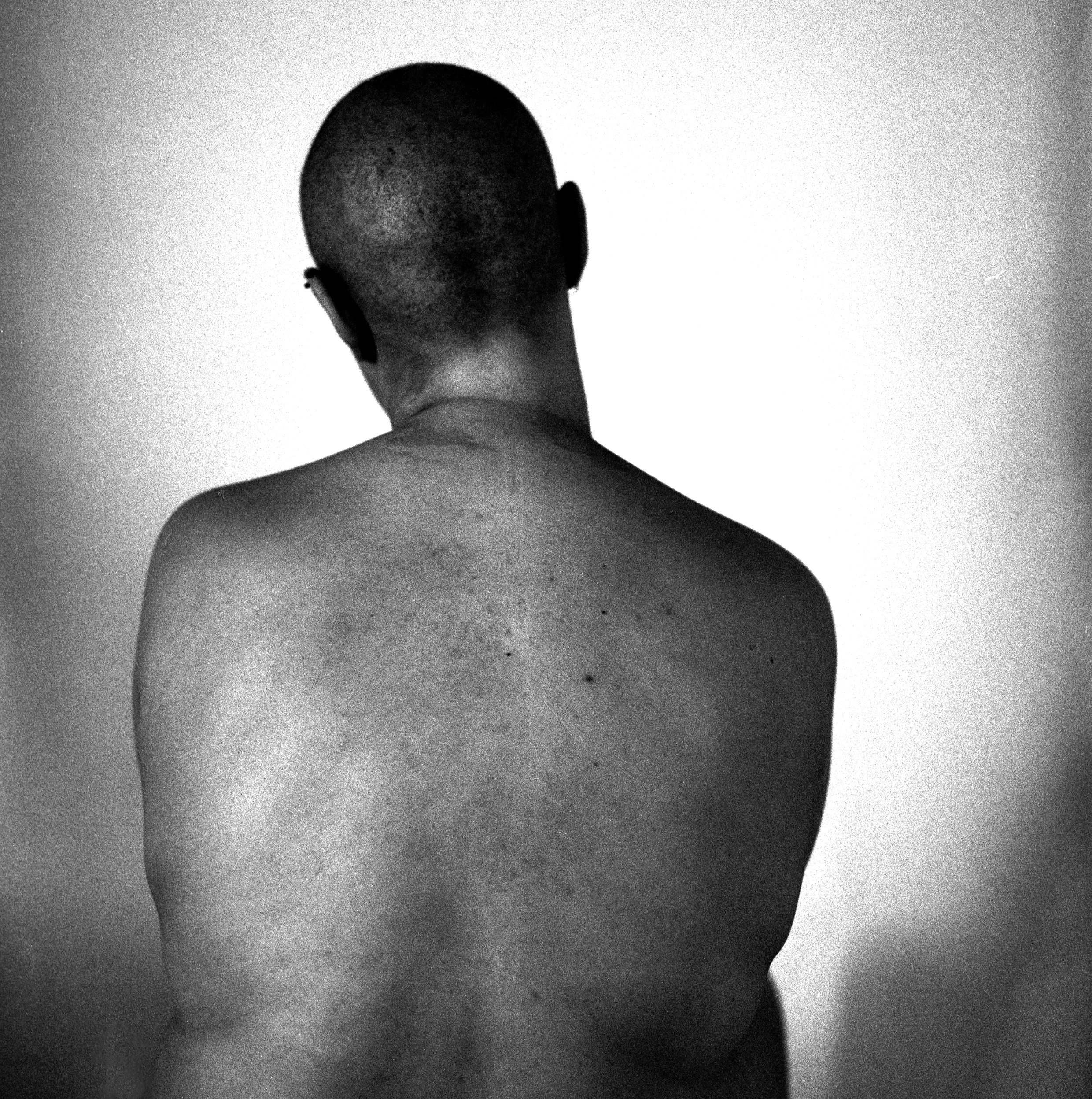

From the series How Was Everything, Before All This Ruin? © Ameen Abo Kaseem

A collective for photobook-makers in the SWANA region, aka TAWLA aims to highlight their narratives and recently created a publication featuring Palestinian photographers

“It started with a table, and then it got bigger,” Abdo Shanan tells me from his Algerian home. On the other half of the screen Rehab Eldalil is laughing and playing with her daughter at the American University in Cairo, where she is currently based. Shanan and Eldalil are the two people behind aka TAWLA, a collective for photobook-makers from the SWANA region (South-west Asia and North Africa). ‘Tawla’ translates as ‘table’, and a table was truly the beginning. The first time I met them was on a rainy day in Paris at the Polycopies book fair, at the table on which they were presenting Tarweedeh – the collective’s first publication.

Eldalil is an award-winning photographer and visual storyteller, most recently recipient of the World Press Photo Regional Award 2022 (Open Format/Africa) and the Premi Mediterrani Albert Camus Award 2022. Shahan won the CAP Prize (Contemporary African Photography) in 2019 and the Premi Mediterrani Albert Camus in 2020. Both use photography as a way to understand and comment on their own communities. Both felt extremely frustrated with the photography and visual arts industry at large, especially after the most recent Les Rencontres d’Arles – about the lack of representation and recognition of non-western photographers, particularly from the SWANA region, and their difficulty in accessing spaces and stages that are perceived as international. “It is important for us to reflect both on who tells our stories, and who we produce these stories for, where we disseminate them,” they say. “We want some form of control over it.”

“There are so many incredible books and dummies produced by photographers in the region that do not find their way out, because of the lack of interest from established western publishing houses”

Funding support

Eldalil and Shanan are alumni of the Arab Documentary Photography Program (ADPP) – a scheme developed by the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC), with Dutch NGO the Prince Claus Fund, in partnership with Magnum Foundation in New York. ADPP is a gem of the photographic industry, pledging continuous support to cultural practitioners and alumni alike in the Arab region.

The Beirut-based AFAC was founded in 2007 as an independent foundation, an initiative of Arab cultural activists to support photographers and organisations from the Arab region. Focusing on the broad spectrum of the cultural and artistic fields, AFAC has so far supported well over 2000 projects, covering cinema, photography, visual and performing arts, creative and critical writing, music and documentary film, in addition to the special programmes, North Africa Cultural Program and Arts and Culture Entrepreneurship Program, granting a rough total of $44million over 15 years.

“Our goal is to be a supporting institution, rather than a controlling one,” AFAC director Rima Mismar says. “Our grantees have complete freedom in developing their projects, and we strive to be there should they need us. We provide guidance and mentorship when it comes to skills and practices, with the long-term goal of also creating a network of practitioners in the region. It is a reason of pride for us that previous grantees take part in the jury sessions for the future cohorts; it contributes to creating a legacy.”

AFAC’s focus on photography developed in more depth after 2014, when the ADPP was founded following a proposal from Susan Meiselas, Magnum photographer and president of the Magnum Foundation. Yet, as Meiselas and Kristen Lubben, executive director, state: “Since the programme’s founding 10 years ago, we have developed deep and ongoing relationships with the ADPP photographers. Through the programme, they develop as artists and also become members of a mutually supportive and sustaining creative community. Magnum Foundation’s goal is to extend that community by sharing opportunities and trusting the photographers when they come to us with new and innovative ideas to activate their own projects or amplify the voices of fellow storytellers from the region.”

The Prince Claus Fund has a similar approach, supporting arts and culture in countries in which cultural expression is under pressure, but taking a hands-off approach. It did not have a specific role in the extra funding for Tarweedeh but, Tessa Giller, head of programmes, says: “We have been supporting AFAC, and specifically the ADPP programme, for years now – and it is our intention to continue doing so. We are very happy with the outcomes of it. We tend to look at eventual additional support when practitioners reach out to us, and we evaluate them case by case.”

Creating aka TAWLA

The ADPP yearly grant is open to documentary photographers who work with creative photography practices in the Arab world. It provides up to eight photographers with a $7000 grant to work on projects in their country of residence over a period of 10 months, during which they participate in three workshops plus benefit from one-on-one mentorship. AFAC’s Rima Mismar continues: “We realised how important it is to follow up and be there for them after their project is completed. Diffusion and dissemination are important aspects, and we want to be active in that sense as well.” For this reason, and in celebration of its 10th year of activity in 2023, ADPP launched the Arab Documentary Photography Program Alumni Fellowship, committed to “accelerating the careers of the programme alumni by providing them with the support and resources they need while facilitating further regional and international exchanges between established and emergent photographers”.

Before this new programme was launched, in summer 2023, Eldalil and Shanan thought of reaching out to ADPP and Magnum Foundation to see if they would financially support them in getting a table at Polycopies (after the encouragement of Jessica Murray, ADPP coordinator). The original idea was to present their own books, but they opted to also invite photographers from the ADPP community and beyond. They then decided to present themselves as a collective – aka TAWLA.

“There are so many incredible books and dummies produced by photographers in the region that do not find their way out, because of the lack of interest from established western publishing houses, but also support in diffusion and distribution. Aka TAWLA was born with the desire to fill in for such a need, and create our own platforms and opportunities,” Shanan tells me. “When we created it,” continues Eldalil, “we did not know if fellow colleagues would trust us in presenting their books. In December, in Cairo, we had to have a double table to be able to include all the publications given to us.”

During that rainy November day, seeking refuge in the welcoming Polycopies barge, I heard Eldalil introducing Tarweedeh during one of the programmed talks. The publication was created out of the urgency to address the devastating war on Gaza, and the need to support the photographers in the field. Featuring works by Maen Hammad, Randa Shaath, Samar Abu Elouf, Sameh Rahmi, Tanya Habjouqa, Samar Hazboun, Ameen Abo Kaseem, Lina Khalid and Nadia Bseiso, its purpose is to be a “tool of resistance, hope, and solidarity that came to exist through our belief in the power of images and self-representation to create connections”. Its title is explained on its first page; it refers to “an encrypted style of Palestinian folk song used to help families communicate across occupier prisons. This type of folk song was first developed during British colonisation of Palestine, and continued after the Nakba in 1948”.

In September 2023 violence in Gaza and the West Bank was escalating, before the tragic attacks of 07 October. In response to the deteriorating situation in Gaza, especially in relation to the safety of journalists and photographers in the area, aka TAWLA decided it urgently needed to put “something out there”, a visual testimony of the stories and practices of Palestinian photographers. The alarming death toll since has only served to illustrate how prescient aka TAWLA’s initiative was, underlining the need to allow the space for on-the-ground narratives.

Aka TAWLA reached out to ADPP and Magnum Foundation again, and both were happy to provide additional funding. Having secured the money for printing, Tarweedeh was officially in-the-making. Eldalil took care of the editing, often having to use images already in the ADPP database because it was impossible for the Palestinian photographers to send new files. “It was an enormous gesture of trust. They gave us their works, giving us carte blanche, trusting that we would give justice to their stories. But it was all very quick, very urgent,” she explains.

“Our goal is to be a supporting institution, rather than a controlling one… Our grantees have complete freedom in developing their projects, and we strive to be there should they need us”

Visual testimony

The nine featured portfolios take the viewer through the personal stories, aspirations and narratives of the photographers, in pages designed by Reem Attia and also including drawings by Sabbagh and Maggie Ashraf. War and destruction is always in the background, an unavoidable constant causing displacement and shattering lives. Yet what stands out is a longing for normality, for a sense of place that resembles home, and a sense of being able to restore, in a precious, delicate way, some form of civil contract of photography.

Maen Hammad’s images are “inspired by the profound connection between skateboarding and space”, for example, highlighting the “juxtaposition of violence and joy for young people in Palestine”. He is also one of the photographers documenting the situation in the occupied West Bank since 07 October. Lina Khalid documents her time battling cancer, capturing “the ghosts that haunt her in the form of pain, love, loss and death”. Ameen Abo Kaseem reflects on the trauma of displacement, and on the helpless status of refugees, treated as strangers wherever they go.

Randa Shaath’s images from the turn of the century show a routine we almost cannot fathom today. Samar Hazboun focuses on the stories of some 67 Palestinian women forced to give birth at checkpoints between 2000 and 2005, “by pairing portraits with relevant belongings of the subjects involved”, including premature death certificates and clothes prepared for children who never wore them. Samar Abu Elouf depicts life under constant power outage, and lack of electric light. Sameh Rahmi reflects on the everyday life of some of the 1600 amputees living in Gaza; numbers that will have undoubtedly changed since October. Abu Elouf and Rahmi had been residing in Gaza; while Abu Elouf was recently evacuated, Rahmi remains in Gaza with his two daughters.

Tanya Habjouqa creates a collective portrayal of humanity’s ability to seek pleasure and joy under the most testing circumstances, and Nadia Bseiso documents the landscape of several villages along the borders of Palestine, Iraq, Syria and Saudi Arabia – reflecting on the relation between humans and land, and the latter’s challenged fertility due to water scarcity. Through these pages are many elements speaking of the function of photography and image-making, their power in conveying narratives and addressing complex matters, and as tools of resistance and empowerment.

Produced at speed, with 200 copies printed in Paris given away by donation and proceeds entirely going to support the featured photographers in Gaza, Tarweedeh quickly sold out. It was reprinted for subsequent showings of the aka TAWLA table at the Cairo International Book Fair and Magnum Foundation in New York for the latter’s December public programme (where it remains available, and is now in its second printing), along with further editions and events in the works in other cities, such as Barcelona and Dubai.

Eldalil and Shanan say they were not expecting the solidarity and support they received from Polycopies onwards, either in the Arab region or the west. “There are monetary resources, which are absolutely necessary for allowing any project to take off the ground, and for which we are grateful, and there’s other resources – trust, solidarity, support, making space and creating spaces,” Shanan states. “All of this is wealth, and we all can benefit from it, if we start understanding its power and potential.

“It’s about shifting dynamics and creating new strategies with human relations at their core. Since Polycopies, aka TAWLA collective has been joined by two new members, Mohamed El Mahdy (from Egypt) and Fethi Sahraoui (from Algeria). The aka TAWLA collective community also keeps growing across the region, as more visual artists share interest in showcasing their work with us.” As Shanan says, it is about starting with tables and letting them become bigger.