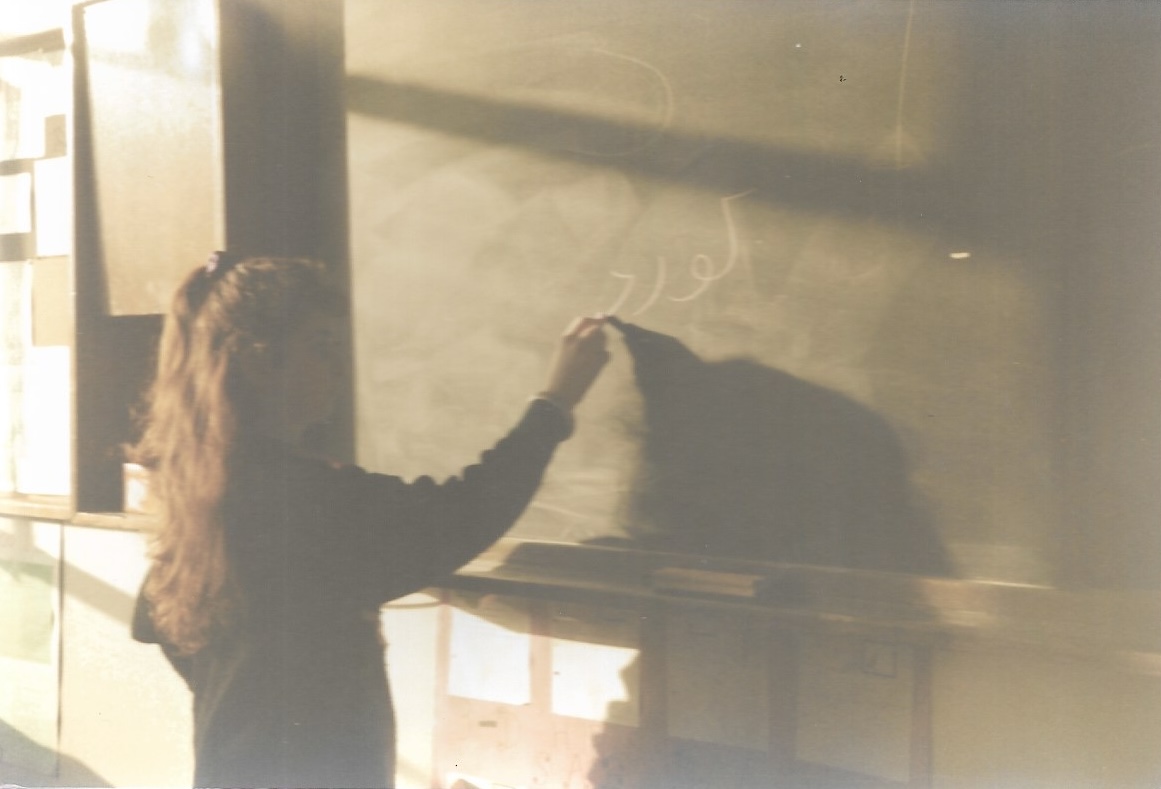

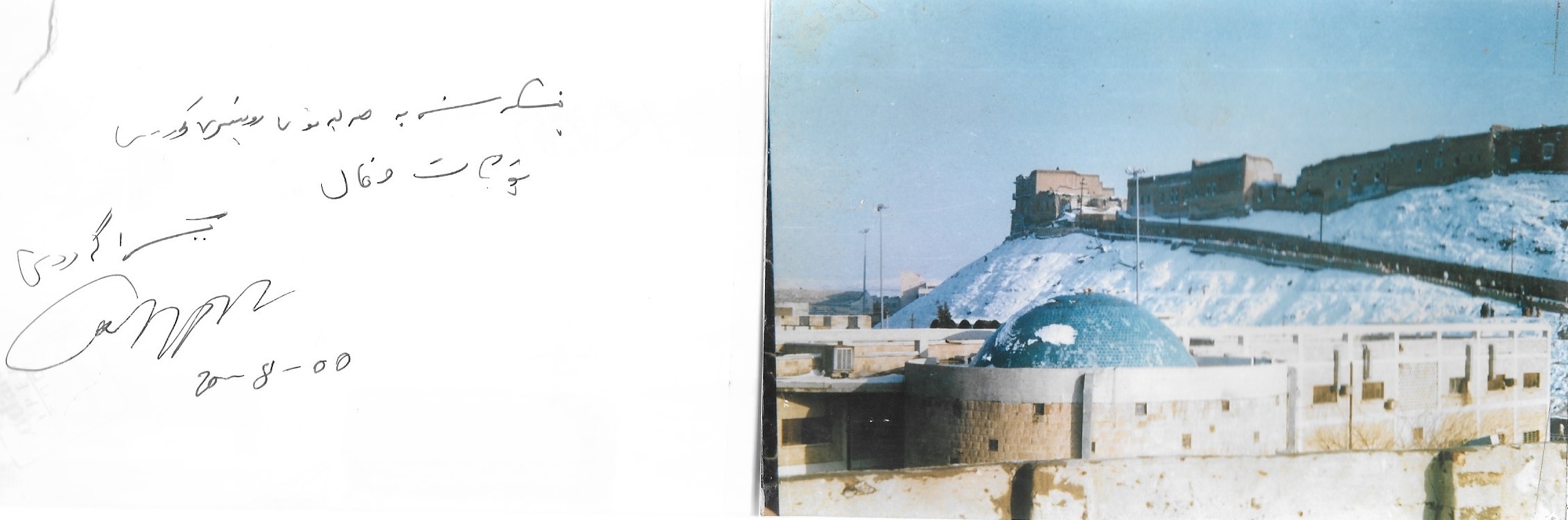

The Lebanese Archive by Ania Dabrowska, Courtesy of the WANAWAL

The West Asian and North African Women’s Art Library explores what roles photography and archives play for diasporic and marginalised communities

‘Decolonial’ has become a buzzword. But what does it look like to decolonise a practice? The West Asian and North African Women’s Art Library (WANAWAL) shows us how it’s done. Founded in 2019 by archivist and artist editor Êvar Hussayni, this collection has been meticulously curated to challenge conventional archival methods and embrace a more inclusive, experimental approach. WANAWAL’s inaugural exhibition, don’t worry i won’t forget you, not only showcases the sheer volume of works within the collection but also invites visitors to engage with the material, fostering a space for collective memory and liberation.

Upon entering South London’s Forma, the viewer is met by a homely space with rugs, mid-century bookshelves and plenty of comfy chairs. The space was intentionally organised to welcome engagement with the books and materials, which challenge colonial methodologies of archiving. The library consists of books and material by majority women and femme practitioners from West Asia and North Africa, spanning fine art books, radical literature, photo albums and photobooks. By questioning the dynamics of archiving, WANAWAL seeks to reshape narratives and dismantle the impact of colonial practices on collective memory.

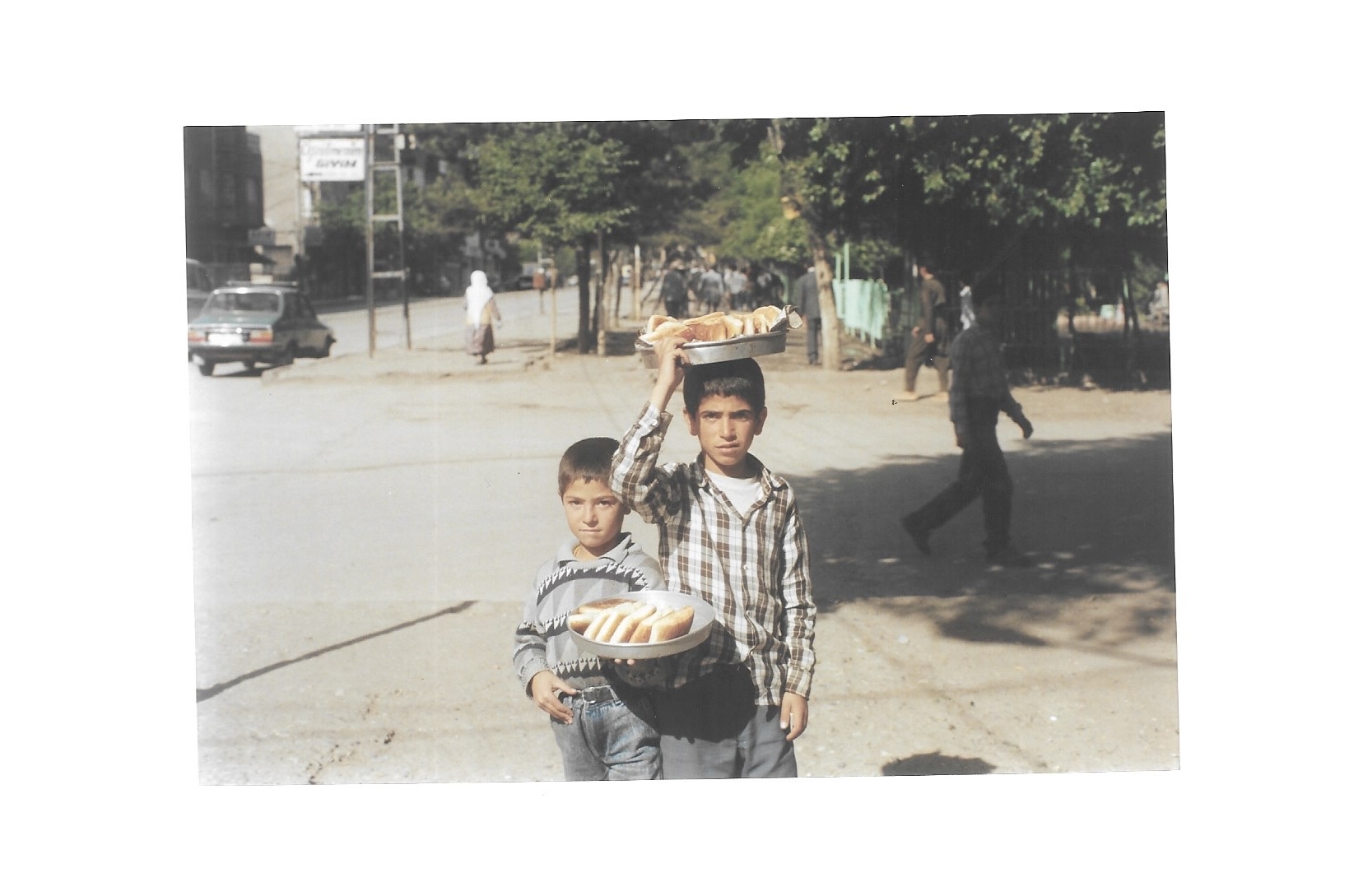

Since its inception, WANAWAL has been dedicated to exploring the impact of archives – how they can shape, modify, harm, or save communities. One such archive consists of undeveloped negatives from Kurdistan and Levant which Hussayni acquired from an eBay seller (who she had to barter with on the price). The viewer inserts each negative, which is held in a small square case, into a slide viewer and holds it up to see the picture come to life, which could depict family life at home, a celebration such as a wedding, or a natural landscape. The approach is one of curiosity, discovery, and an openness to imagining alternatives to the present. As Hussayni explains, “I wanted to create a space for people to feel comfortable enough to engage with the archive outside of rigid systems or institutional, colonially-influenced methods.”

“I have been so utterly in love with the most chaotic, reflective, gentle, and hilarious process of making this exhibition”

By creating spaces and maintaining an open-source online library, WANAWAL ensures that the archive remains a living entity, continually updated with contributions from artists, researchers, curators, and creative collectives, such as Meriem Bennani. The artist explores documentaries, phone footage, animation, and high-production aesthetics and contributed the humorous film FLY (2016), a 17-minute fly-on-the-wall video of everyday Moroccan life, to the Forma show.

“In creating spaces for the physical exploration of the archive, WANAWAL invites your curiosity and tangible connections to the archive in whatever ways you see fit,” Hussayni states. “[The collection] has been able to reach a place of experimentation and adaptation to nurture ideas around collective memory as a liberation practice.” The main living room area allows visitors to sit in a large armchair, for example, and watch home videos of Palestine and the Levant.

Inviting Sarah Hamed to co-curate brought essential insight, enhancing the exhibition’s depth and coherence. The process involved detailed consideration of every aspect, from the political implications of the exhibition to the spatial arrangement of artworks. “I have been so utterly in love with the most chaotic, reflective, gentle, and hilarious process of making this exhibition alongside Sarah and equally when we brought in Olivia Melkonian to curate the Sound Archive,” Hussayni says.

Melkonian’s contribution as the curator of the Sound Archive saw techniques and research methods highlighting the importance of audio materials in understanding identity and history. “She engaged with the materials so beautifully and with so much care and dedication to understanding what it means for people to have access to audio materials,” Hussayni notes. Melkonian included records from across Libya, Lebanon and Sudan, among other regions, and cassette recordings of archival radio sessions playing Kurdish folk music retrieved from the Kurdish Cultural Centre in Oval, which is now almost abandoned.

While WANAWAL’s archive and library encompass various media, photography plays a pivotal role. Photographic archives offer insights into the sociopolitical and cultural conditions of different times and communities, contributing to the collective memory of societies. The Kurdish Cultural Centre’s archival images provide a snapshot of not only personal histories and experiences of a group under threat of erasure, but also a memento of when the Centre itself was a thriving hub for the Kurdish community. Within WANAWAL, the photographic archive helps contextualise materials and moments, enhancing our understanding of the work produced by the practitioners.

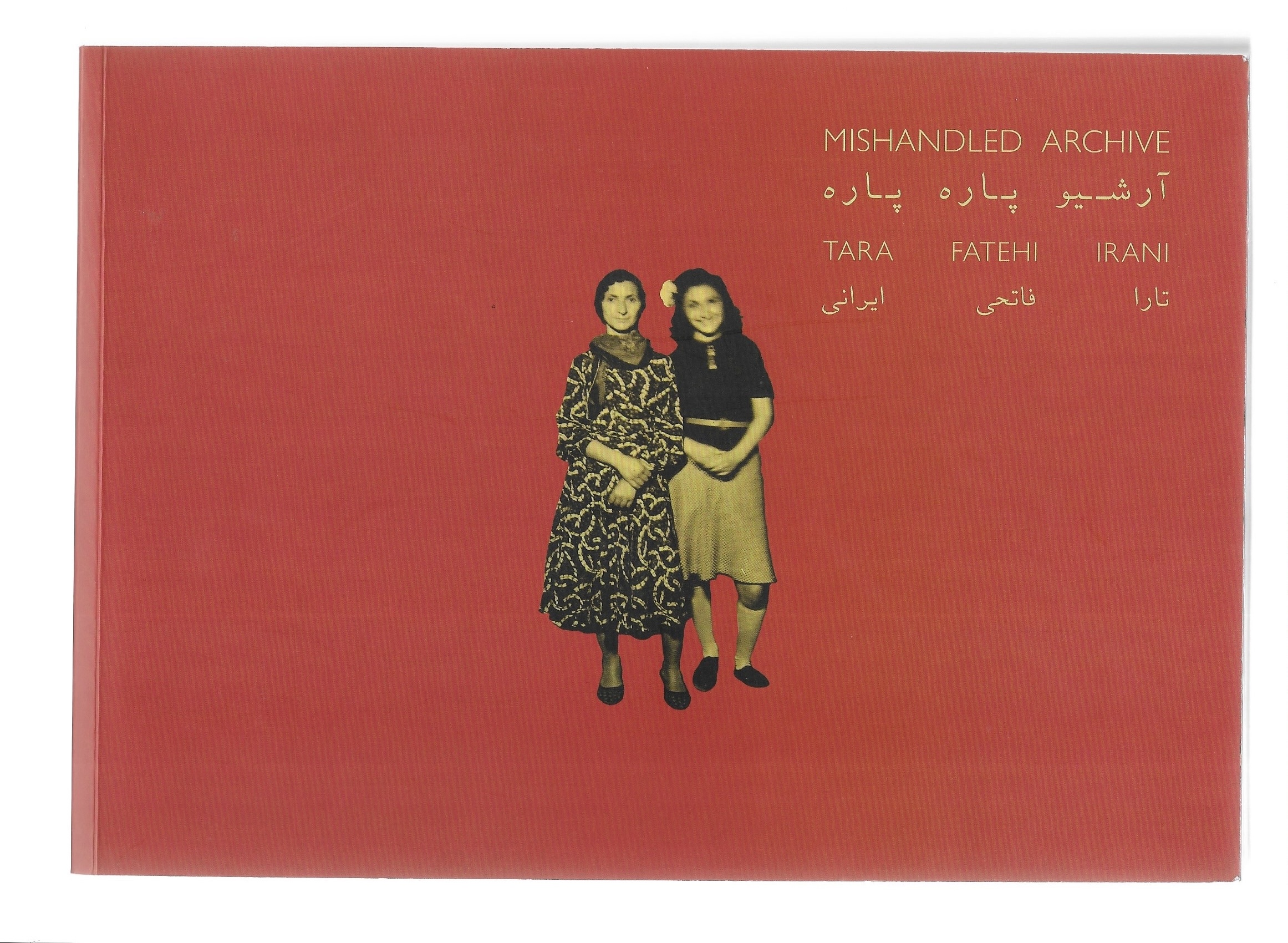

“The camera allows practitioners to document their process and ensure the eternalisation of their thoughts, experimenting methods and research,” Hussayni says, explaining that photography has significantly influenced our understanding of archives, providing visual evidence that complements and sometimes challenges written records. This rings true especially for photobooks in the collection, which hold particular significance for Hussayni.

The Lebanese Archive, a collection of archival photographs from Lebanon and the Levant which came into the possession of Ania Dabrowska from the collection of Diab Alkarssifi, introduced the founder to archives. “Before that, my practice was trying to navigate ideas around ‘documentation’ and what that means in the context of Kurdish people, history and culture,” Hussayni recalls. “When I was introduced to this book, I realised my work was archiving.”

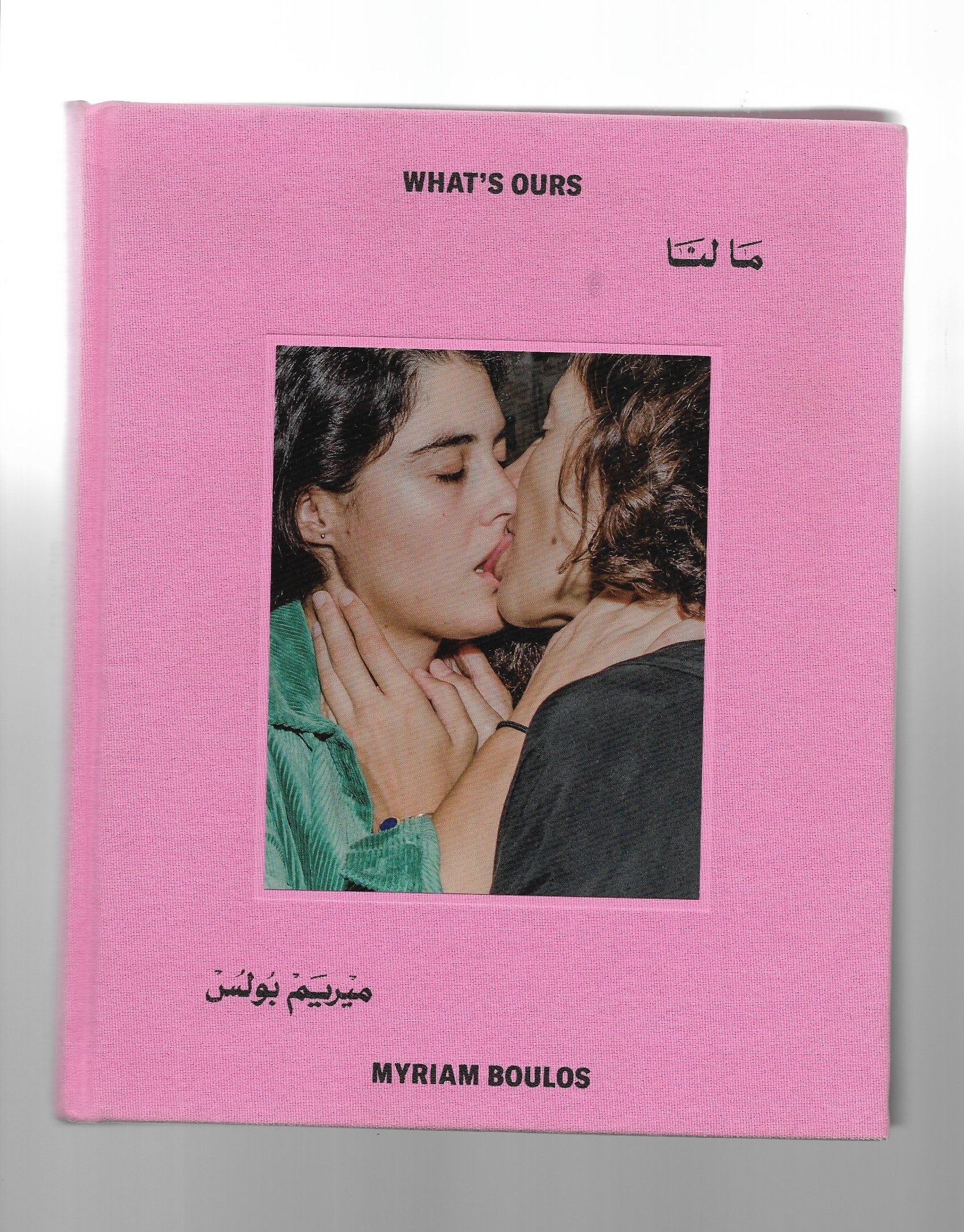

Whereas Kurdistan by Susan Meiselas is an exemplary blend of archival photos, new photographs, documents, texts, and maps, this book offers an authentic narrative of Kurdistan. “It is a very wholesome example of how easy it is to tell stories authentically,” Hussayni notes. And What’s Ours by Myriam Boulos is a powerful portrayal of Lebanon’s revolution from 2019 to the aftermath of the Beirut port explosion in 2020. Boulos captures intimate moments of pleasure and protest, reflecting the multifaceted works of WANA practitioners.

don’t worry i won’t forget you is an invitation to engage with an evolving archive that challenges traditional narratives and promotes inclusive, liberatory practices. By presenting the WANAWAL collection for the first time, the exhibition opens a dialogue about how archives shape collective memory and identity. Visitors are encouraged to explore, connect, and discover, making the archive a living, breathing entity that continues to grow and inspire.

don’t worry i won’t forget you is at FormaHQ, London, until 10 August