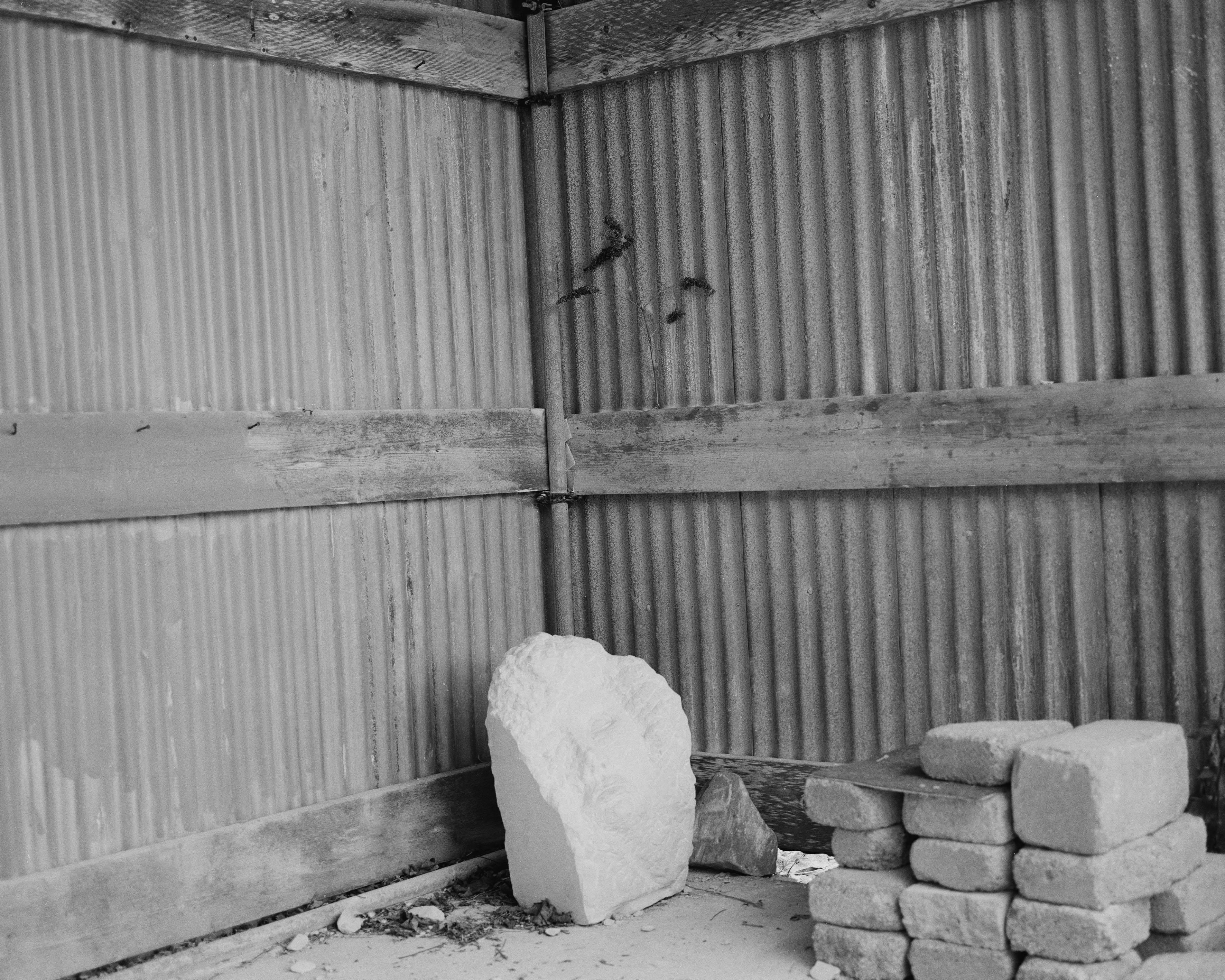

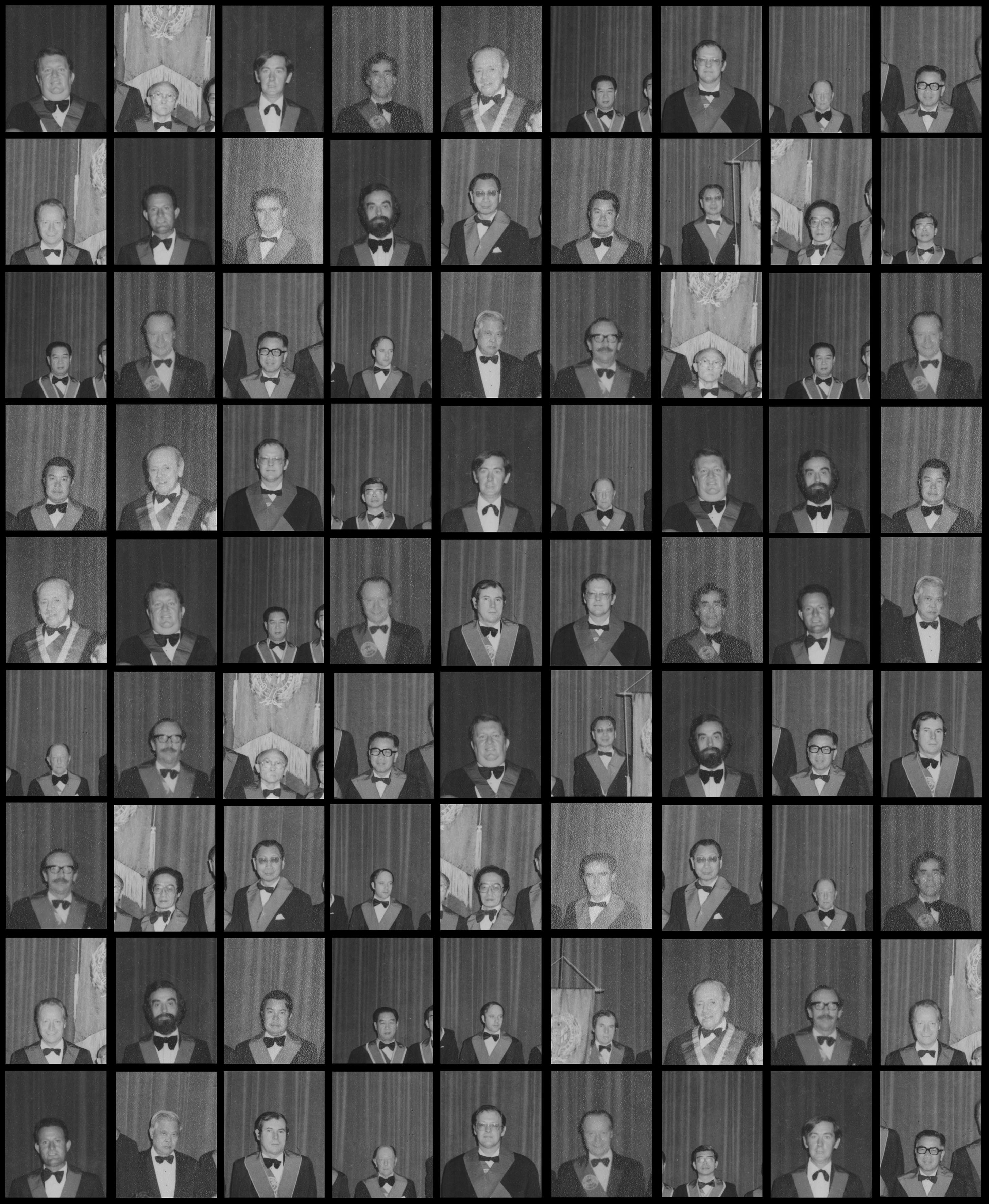

Brother Barton. All images © Lily Barton from Snakes and Ladders

Long fascinated by her family’s association with the secret society, Lily Barton went in search of concealed truths – camera in hand

When photographer Lily Barton was growing up in Dorchester, south west England, she knew her grandfather was a Freemason, but had little idea about what this involved. She was told not to look in his wardrobe or briefcase, and often wondered why he had an office in his house, even though he appeared not to work. As she got older, Barton accompanied him to his masonic lodge’s Christmas parties in a windowless building – “a ritual growing up” – but the pair rarely discussed her grandfather’s role or the exact details of the fraternity. She remained a curious and slightly intimidated outsider.

Freemasons, Barton later learnt, are private groups, organised into regional ‘lodges’, descended from the stonemason guilds of the Middle Ages. Often termed ‘secret societies’, these groups allow members to participate in historic ceremonies, social and charitable events, though in much of the public imagination they are defined by their secrecy and almost universal exclusion of women. Barton’s grandfather belongs to a lodge in Weymouth, overseen by the United Grand Lodge of England, the governing Masonic lodge for the majority of freemasons in Wales, England and the Commonwealth. Barton was also aware of Freemason activity around Bath and Bristol, but still her understanding of the groups was relatively detached and academic.

This all changed when Barton was undertaking a BA in photography at Bath Spa university, where she devised Snakes and Ladders, a final project and book inspired by her grandfather’s identity as a Freemason. A combination of original imagery, found photographs from eBay, and wider archival material, the work is an attempt to visualise the unknowability and mystery of the societies, rather than provide a definitive exposé or document. “I wanted to make sure it was my perception of freemasonry – not a factual, ‘this is what’s happening’ project,” Barton tells me.

Much of the project responds to Barton’s unease around Freemasonry’s gender conventions. In fact, making the project granted her access to otherwise closed off spaces, as Freemasons believed that photographic coverage might lead to increased interest from would-be members. “The camera erased the fact that I am a woman,” Barton explains. “I felt like I had this new sense of power.” Barton’s portrait of her grandfather outside his lodge shows him in official uniform – the traditional apron, medals and white gloves – but has a behind-the-curtain feel too, made around the side of a building rather than among the lodge’s shrouded interior.

“I wanted to make sure it was my perception of freemasonry – not a factual, ‘this is what’s happening’ project”

“Snakes and Ladders bonded us in a way, but it has also separated us, which is interesting,” she reflects on the relationship with her grandfather. The book features consecutive pages with a circular cut-out at the centre through which an eye can be viewed; in other archival portraits, she has blocked out the men’s eyes, as if to protect their identities. Intrigue and unresolved secrecy are the project’s lasting messages.

There is a concerted effort to engage with the more allusive and obscure elements of Freemasonry in the project, especially the symbolic importance of snakes and beekeeping. Portraits of a boy with a snake around his neck show Barton creating her own speculations about the future of Freemasonry. The young boy is a volunteer at a reptile sanctuary, but engrossed in the subject and its potential future, Barton sees “a young boy who could potentially turn into a Freemason” – the next generation of men who appear in a passport-photo-like grid arrangement at the book’s conclusion.

Very little has changed in the hundreds of years of Freemasonry, Barton points out, collapsing the temporal gaps between the archival imagery and her modern-day photographs. “The whole project is a flood of emotion,” she concedes – a distillation, rather than resolution, of her views on Freemasonry’s gender exclusion.

And so Barton’s grandfather, ostensibly the origin of the project, becomes subsumed and eventually fades into the decades of tradition and uniformity which define Freemasonry. This is not a topic one can learn more about simply by moving closer, and Barton’s overriding feeling seems to be that Freemasonry clashes with a basic – yet generationally specific – sense of fairness, especially around patriarchy. But Snakes and Ladders remains curious rather than condemnatory, reflecting the mystery and circularity of its subject. “The world has moved on, but they’re very much stuck in the past,” Barton says. “I don’t think that the Freemasons are a group of nasty people, but I think that nasty people can manipulate it and use it to their advantage.”