From Before Freedom Pt. 2. All images © Adam Rouhana. Courtesy TJ Boulting

The Boston artist’s Before Freedom series has captured the minds of gallery goers and activists alike

“I don’t know what to do with seeing anymore,” says Yazan Khalili, the Palestinian academic and artist. “I’m troubled with images. How they hijack our imagination.” Khalili has long been investigating the problem of representation, trying to find ways to create images without recreating power structures. “How do we photograph violence without becoming complicit, without reproducing the violence?” he asks.

For decades, global viewers have been inundated with depictions of Gaza and the West Bank as warzones – rubble, explosions, a suffering people. Though he acknowledges the role of reportage in resisting occupation, Khalili is concerned that the impulse to represent this violence in fact hands the power of defining Palestinian identity over to its oppressors. Instead, he insists on seeing brutality as a defining feature of the perpetrators of violence, not its victims. “Show people a picture of the war, the destruction, and they say, ‘Oh, that’s Palestine’. I say, ‘No, that shows Israel’”.

For Khalili, Palestinian image-making is more about “the poetics of the failure of representation”. In 2009, he completed a series of landscape photographs of Palestinian villages at night, unlit buildings and roads only just managing to expose themselves into the pictures, while beyond the shoulders of olive-groved land the mega-urban light of Israel throbs. “The darkness made it more Palestinian, more organic, more local, more safe,” he says of the series. “Seeing in darkness is part of a power structure – bright cities, military night-vision. Instead, I’m interested in the political structures and the poetics of being in darkness.”

But since 07 October 2023, even these un-images have troubled him. He started attacking his own photographs, tearing out the horizon-lines of his landscapes. Then he simply stopped making pictures altogether. “Many of the structures we rely on for artistic production have enabled this genocide to happen,” Khalili says. “I can’t simply go back to the same modes of production. Everything before 07 October is The Past. What future is in front of us? How do you make photographs now?”

“I want to question photojournalism… appropriate some of its tools but use them to do something different”

Adam Rouhana’s work offers us one kind of answer. The Palestinian-American photographer has just opened the exhibition Before Freedom Pt 2 at TJ Boulting in London – a continuation of his debut solo show at Frieze No. 9, which concluded last month. Before Freedom, an ongoing series begun in 2022, has reached thousands through Instagram. Before these two exhibitions, however, Rouhana’s only presentation in a physical space was a single photograph (the now-iconic image of a Palestinian boy burying his face joyously in a watermelon, the short depth-of-field pulling him into rapturous, intimate focus) which was included in South West Bank at this year’s Venice Biennale.

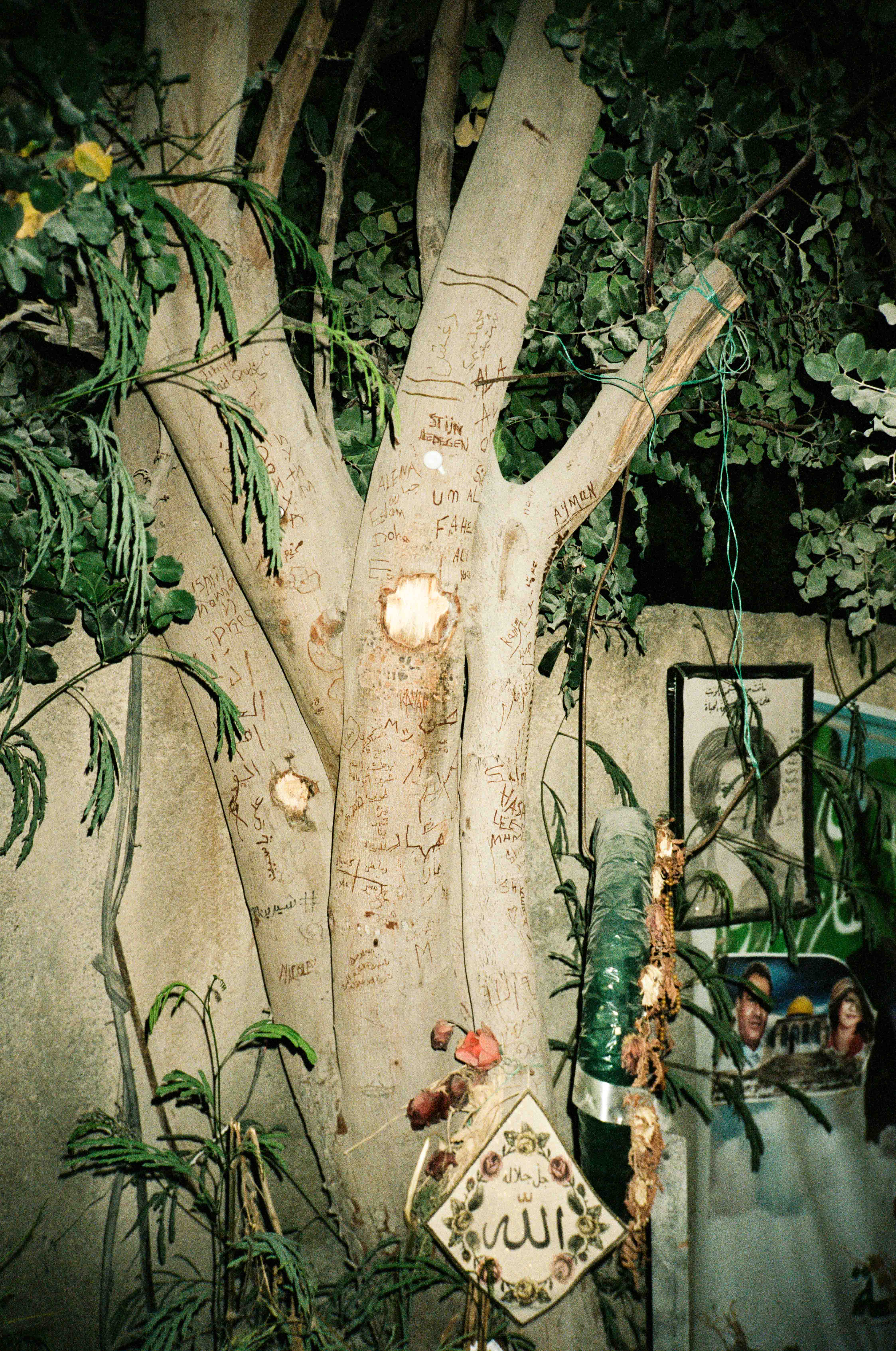

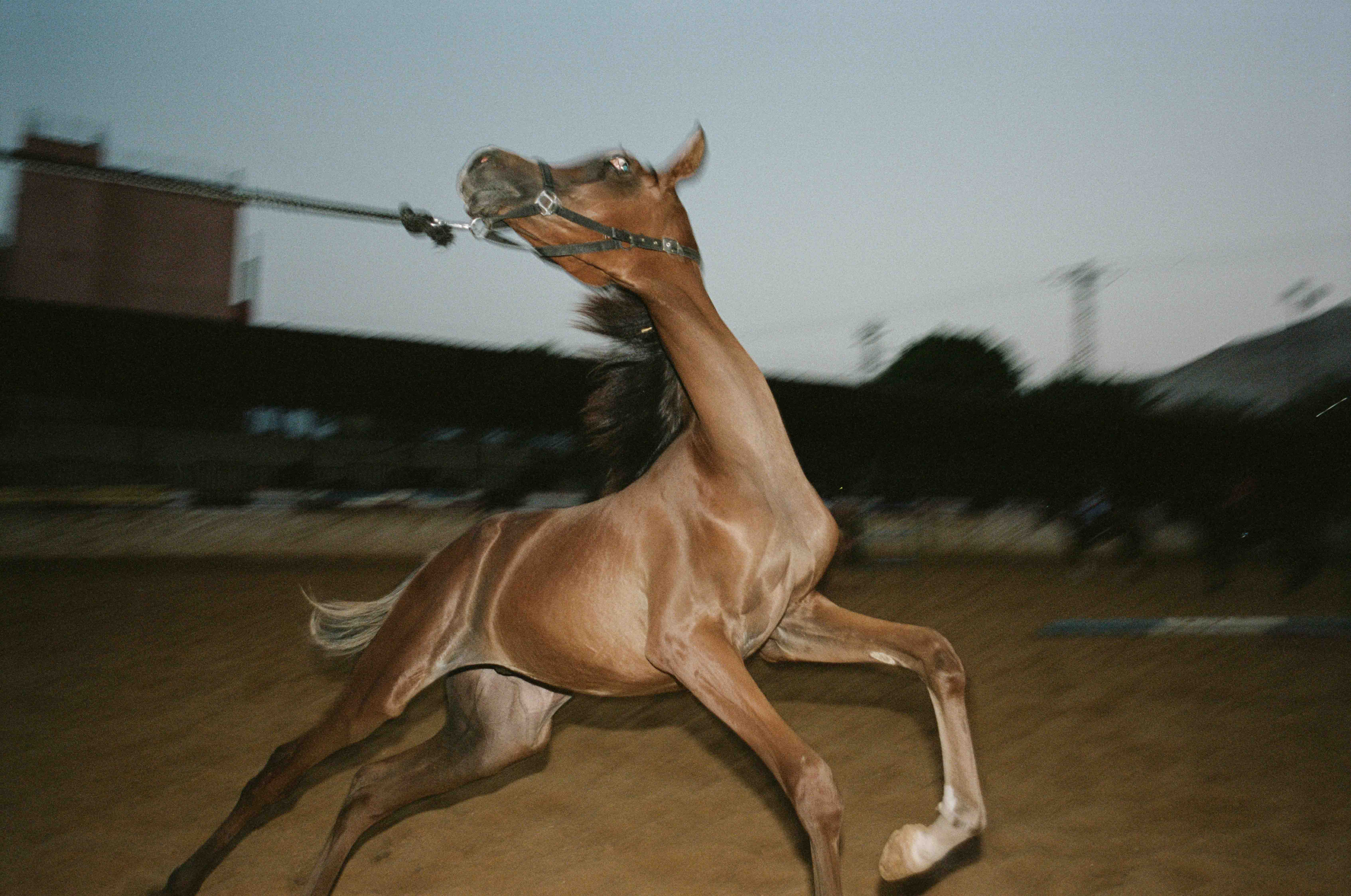

Since 2022, Rouhana’s work has tended to focus on the ordinary experiences of Palestinian people. Children swimming in an urban river; a boy’s legs leaping into the air above the sea; three kids surrounded by the incessant, fructive motion of disturbed olive-tree seeds and airborne insects; a pair of boys wrestling in the dusty greenery of the Palestinian earth, reclaiming acts of violence as acts of play, getting down close to the land, to each other. “We’re so used to seeing Palestinian death,” says Rouhana. “I want to show Palestinian life.”

He describes the genesis of the current project as an act of questioning received image-streams, much like Khalili. “As I started shooting,” he says, “I found myself looking for the images I already had in my mind – to try to recreate them. I searched for a Palestinian boy throwing a rock towards Israeli soldiers, an olive tree burning to the ground, the machineries of apartheid etched into the landscape. But at a certain point, I stepped back and asked myself: Why am I trying to recreate these images of a place that I know so well?” Like Khalili, he rejects suffering as the defining characteristic of Palestinian identity. “I thought: What if I turn the camera away from the violence and away from the images I had in my head, and toward Palestinian life? And this is how Before Freedom was born.”

If Rouhana’s instinct is to complicate the constant stream of pictures that represent Palestinians as a suffering, occupied people, this instinct has had to be adjusted in addressing the present moment. Rouhana’s big, playful prints of the daylight lives of Palestinians have, in the TJ Boulting exhibition, been paired with smaller images acting as companions, commentaries. A picture of two children at play submerging their faces in the pearlescent water of a river appears next to a smaller frame showing a bloody handprint on an interior wall. Suddenly, the image of children face-down in water is more troubling than touching.

As curator Lobna Sana explains, this is a creative decision based as much in aesthetics as it is in modes of address. In discovering Rouhana’s images she found work that “expressed something I could not put into words. To do with the beauty of life in Palestine but also the complexity and sometimes even the shadowness”. Alongside an appreciation of Rouhana’s bright, living pictures, Sana says, “I related more to his shades”. And so the decision to pair the large photos with smaller, less bright frames was reached. “It means the bigger photos, they’re less of a hero. I don’t really like the idea of heroism.”

Sana and Rouhana’s collaboration is a close one. “What I have in my head is the same as what Adam has in his head,” she explains, “even if we don’t express it the same way.” She is Bedouin, and her own artistic practice involves mapping historic Bedouin settlements absent from official records. While describing to me the locations in which his photos were taken, Rouhana pulls out his phone and brings up Google Maps, using his fingers to drag and pinch-zoom our digital viewpoint, flying at will over borders imposed by the Israeli state, ignoring the map’s nomenclature and using his preferred place names (anywhere within the borders of present-day Israel he terms “1948 Palestine”, calling back to the pre-Nakba era) to illuminate his points and tell his stories.

Does all this work of ‘illumination’ risk doing what Khalili fears – “hijacking the imagination” with pictures that reproduce the power structures which enable oppression of their subjects? Does Rouhana’s closeness to photojournalistic styles and settings risk complicity in an image-stream that overwhelms a viewer into inaction? The answer is probably yes, but for Rouhana and Sana this risk is crucial to the creative act. Rouhana is not a photojournalist, he’s an artist. And the key to his vision is getting inside the world of images, being in darkness so as to allow your eyes to readjust.

Two pictures in Before Freedom Pt 2 communicate this most successfully. Both are taken at Checkpoint 300, the infamous crossing point between Bethlehem and Jerusalem through which 15,000 Palestinian workers usually pass daily in the darkness of early morning. Since 07 October, Israel has even further restricted the movement of Palestinian workers under occupation, closing some crossing points permanently and others at random hours of the day (Checkpoint 300, once a 24/7 crossing, closed for a month, then was reopened with very restricted hours). “There are no lights at the entrance to the building,” says Rouhana, “and these photos are taken around four or five in the morning, when the crossing is usually busiest”.

“I want to question photojournalism,” Rouhana continues, “appropriate some of its tools but use them to do something different”. One of the Checkpoint 300 pictures shows a roll of film printed at 28 x 150cm. The very left of the frame is light-damaged, thousands of kettled commuters obscured by overexposure. Rouhana allows this to become a comment upon our own overexposure to images of Palestinian suffering. Out of this light-bleed emerges a picture of a man taking a shortcut by climbing over one of the checkpoint’s fences. He holds a cigarette between his lips and judiciously searches for a handhold on the roof. Though the camera’s flash picks him out in a harsh blanche amid the predawn dark, it’s a pointedly human image, not the sort we’d see in western news reportage nor even an Al Jazeera photo essay.

Asked why he wanted to present these pictures in their unpolished form as a roll of film, Rouhana says, “One element was obviously to communicate the rawness of what’s being shown”. But “we also wanted to find a modality by which this sort of thing could be imagined as The Past. With the other photos, those taken in natural light, they show the present and the future of Palestinian lives. This series, looking like a strip of frames dug out from an archive, envisions apartheid as the Palestinian past.”

In the other Checkpoint 300 picture, the crossing’s corrugated ceilings, metal scaffold, concrete walls and iron revolving gates are visible in the background. Daylight is beginning to seep in. The entire foreground is occupied by a blurred streak of white light, weaving and ghosting through the architecture of apartheid. Sana calls it “the glitch picture”.

“I shoot on film with a Leica M6,” Rouhana explains. “It’s a totally analogue machine. Nothing is digital except the light-meter. On this day of shooting, something in the shutter broke. I heard it. It couldn’t fully close. But I just kept on shooting as I normally would. What I realised when I developed the images was that throughout the exposure, all this light was being let through a barrier that’s usually closed. And that’s how I created this image.” His eyes blaze with the significance of the metaphor, but he stops short of bringing down the representational hammer too explicitly.

Even Rouhana’s lighter photographs approach Khalili’s concept of being rather than seeing in darkness, stepping into the othering frames and catastrophising language of photojournalism to recalibrate them into living acts of creativity – a witnessing from within. And those which enter the shadows, depicting more explicitly the realities of violence and apartheid, nevertheless refigure representation as a modality of time, framing them as what will become past, allowing a vision of a different Palestinian future.

Adam Rouhana, Before Freedom Pt. 2, is at TJ Boulting, London, until 22 June