Stray Dog, Misawa, 1971. From A Hunter © Daido Moriyama/Daido Moriyama Photo Foundation. All images courtesy the artist and The Photographers’ Gallery

Curator Thyago Nogueira spent three years working with Moriyama on The Photographers’ Gallery retrospective

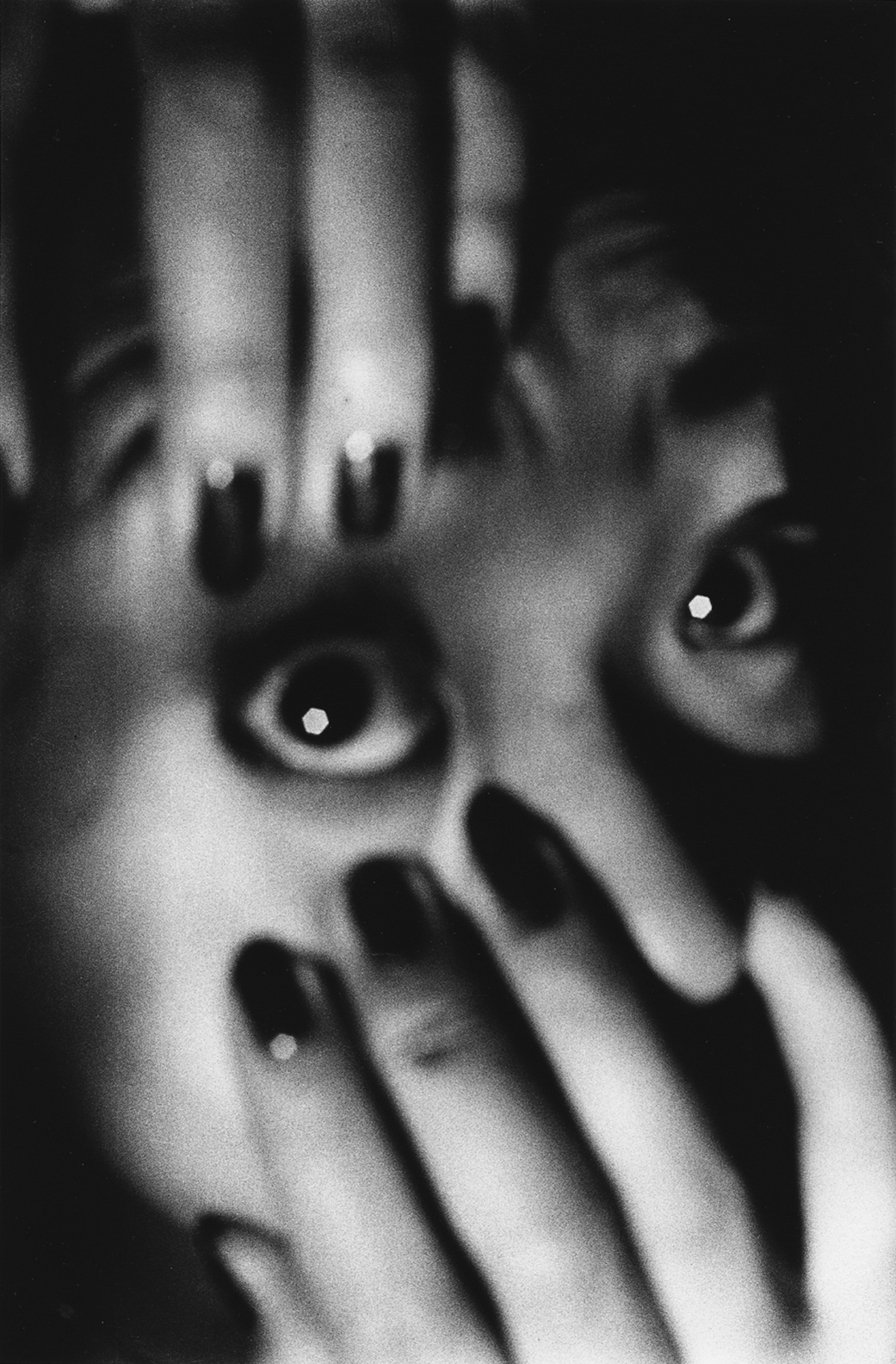

Born in Osaka in 1938, Daido Moriyama is one of the most important photographers in the world. Coming of age at a time of political unrest, when Japan was undergoing significant cultural upheaval, Moriyama worked primarily via radical photobooks and magazines. His first monograph, Japan: A Photo Theatre (1968) is an edgy trip through a fast-evolving Tokyo; from 1969-70 he contributed to Provoke magazine, which celebrated “are, bure, bokeh” [‘grainy/rough, blurry, and out-of-focus’] images in opposition to the then-dominant Western photojournalism and commercial photography.

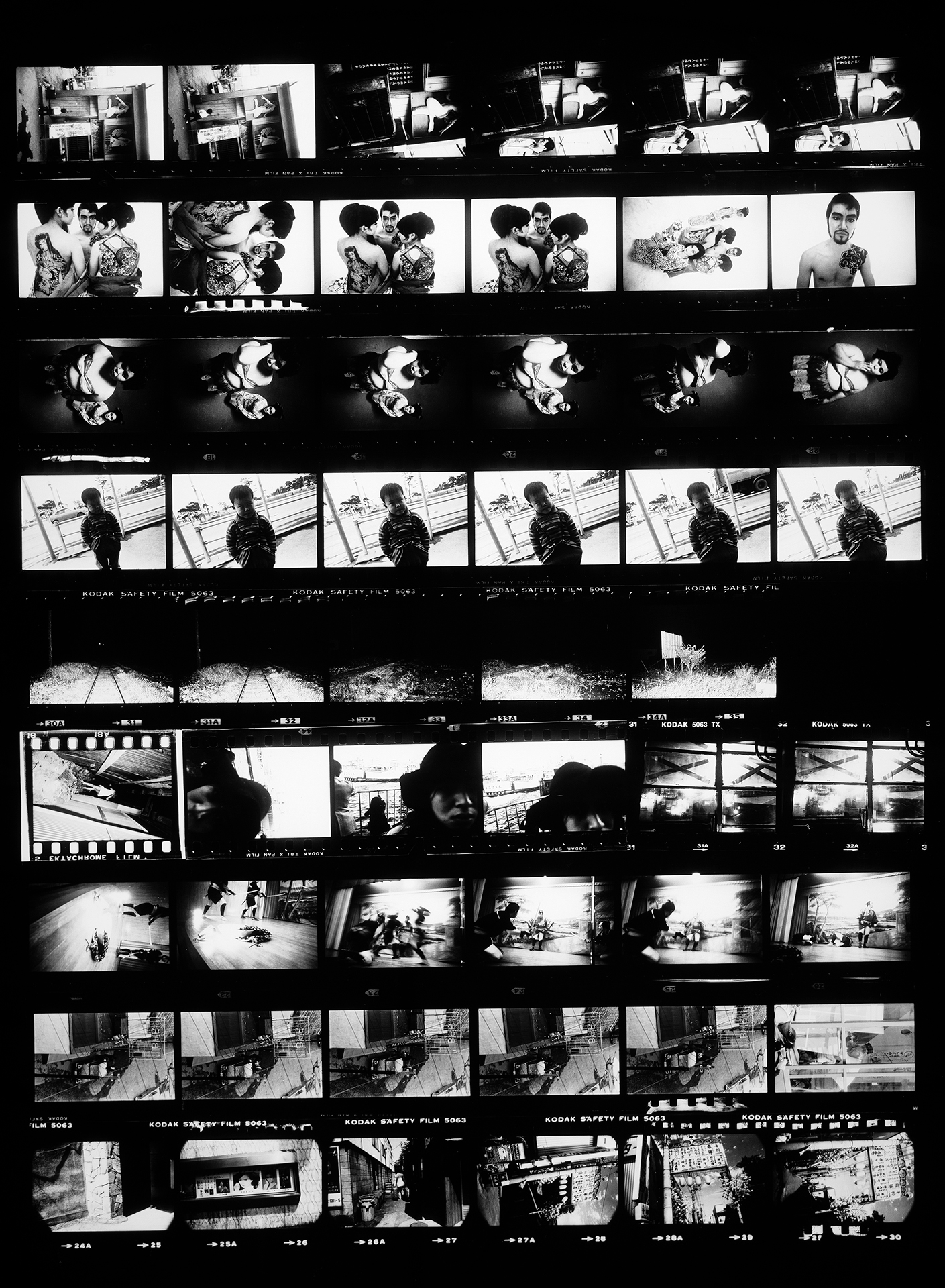

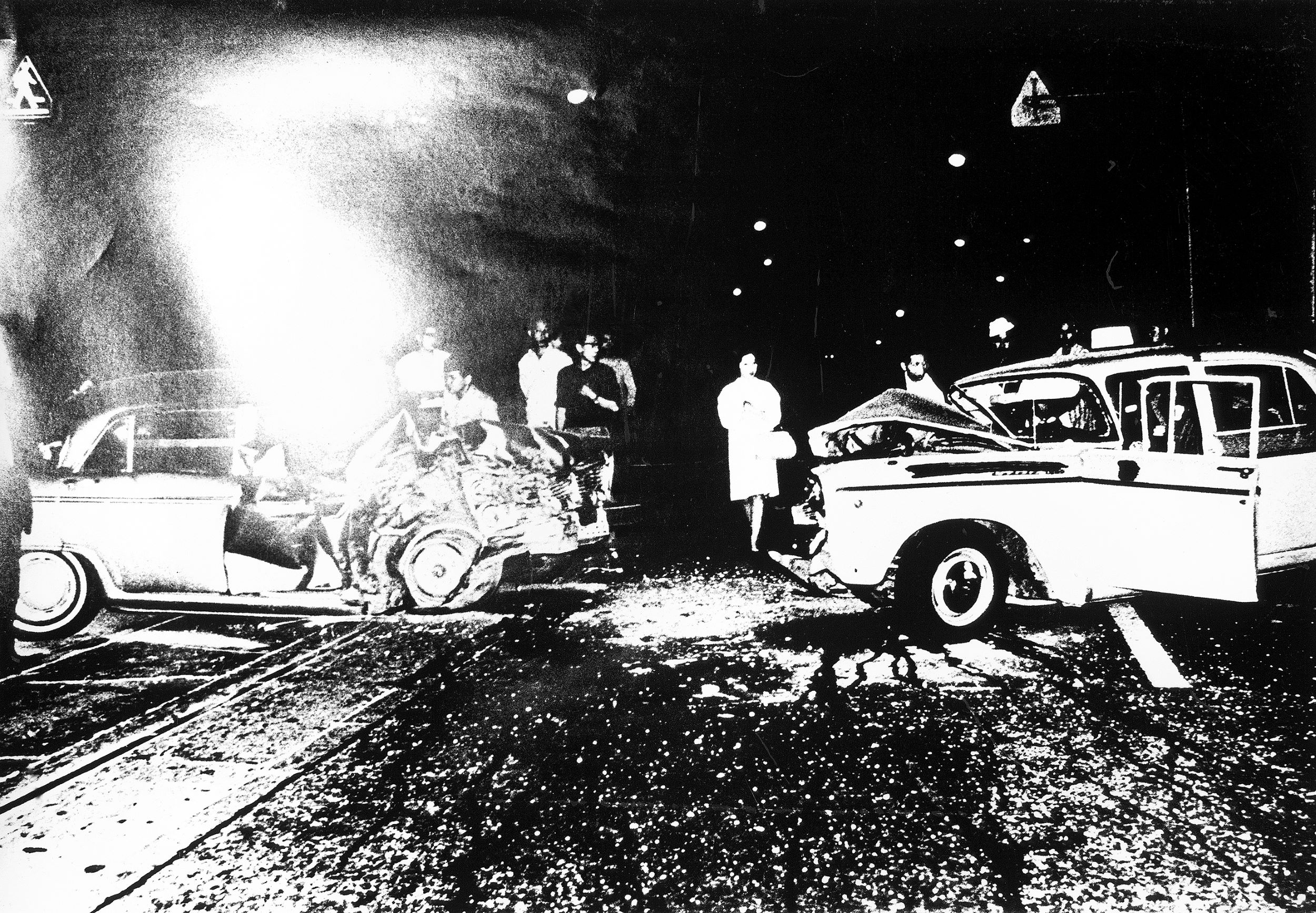

In 1969 he started a one-year series Accident, published in the magazine Asahi Camera, in which he photographed existing images in the media; his 1972 photobook Farewell Photography highlights photography itself, showing edges of discarded film, flecks of dust, and sprocket holes and questioning its role as a medium. Moriyama continues to produce new work, and now photographs in colour and with a digital camera; he has made more than 150 photobooks to date, and exhibited his work at institutions such as Tate Modern, London; Fondation Cartier pour l’art Contemporain, Paris; and Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Daido Moriyama: A Retrospective is now on show at The Photographers’ Gallery, covering the artist’s career from 1964 to the present day. The first UK exhibition to showcase many of his rare photobooks and magazines, alongside large-scale works and installations, it is also the first exhibition to cover the entire gallery, including a reading room with key books by the artist. The exhibition is curated by Thyago Nogueira from the Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo, Brazil, and is the product of a three-year research period with Moriyama.

DS: How did the exhibition come about?

TN: Coming from Brazil, we wanted to look at a photographer that came from a very different background to most of the American or European artists we are used to looking at in photography. We also wanted to look at other paradigms of photography, to try to understand a context where there were no strong institutions or photography collections, where there wasn’t that kind of established infrastructure for photography, but nevertheless – or maybe because of that – very interesting new ideas were being proposed.

I suggested doing a show on Moriyama, and received a grant to go Japan to study his work and archive. That was really mind blowing because, while I knew some of his books, I hadn’t realised how much the books were just a second iteration for his work. Many of these images were originally created for magazines, the Japanese magazines were the exciting places where all the photographers wanted to be, where all the hard conversations around photography were taking place, and where the most original ideas were being posed. I quickly realised that there was a challenge and an interesting question for this show, around how to make an exhibition in a museum focused not on framed artworks for the walls but in a diversity of images that included publications and the printed page.

DS: So how do you go about showing this work in a gallery?

TN: What Moriyama is really saying is that it’s in the nature of photography to be reproducible and replicable. He’s against and not interested in the veneration of artworks, he wants photography to be disseminated. It’s one of his most radical ideas. So we’re presenting plenty of pages from the magazines and books, printed, on the gallery walls and for visitors to browse, and have made videos flipping through each of his really rare books. There’s also a whole section dedicated to seeing the original books. It is going to be a very dense show. But we also wanted to break the hierarchy between a framed picture, a printed image, a wallpaper, and a vinyl. So there are all these different and very interesting kinds of images.

DS: Moriyama is known for his work in the 1960s and 70s, but you have included much more recent images. Can you explain the reasoning behind that?

TN: Even people who know Daido’s production will see how much he has changed throughout his lifetime, while posing the same question – ‘What is photography? What is the nature of photography?’ He has come up with completely different answers to that question, so another challenge was to present those transformations.

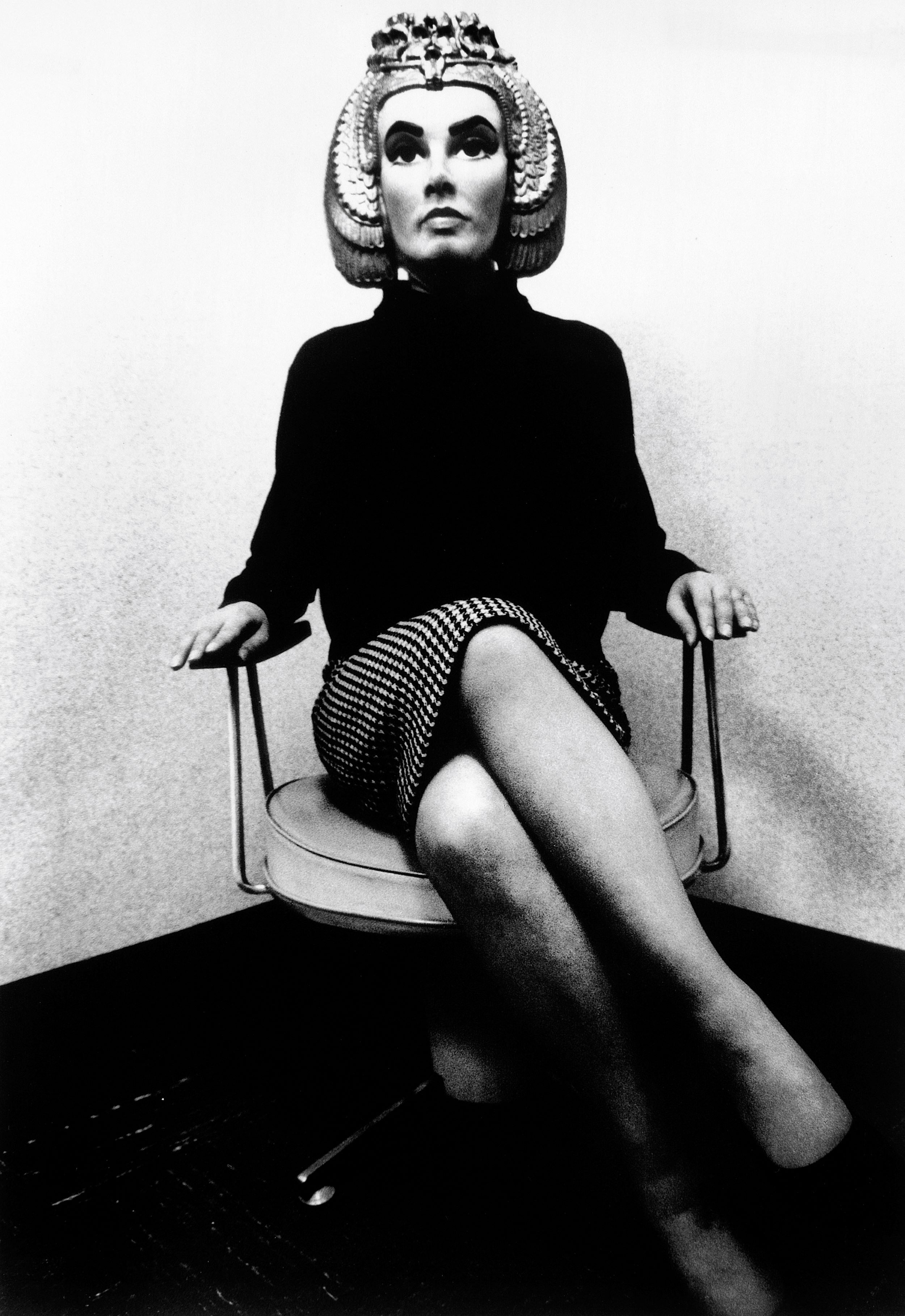

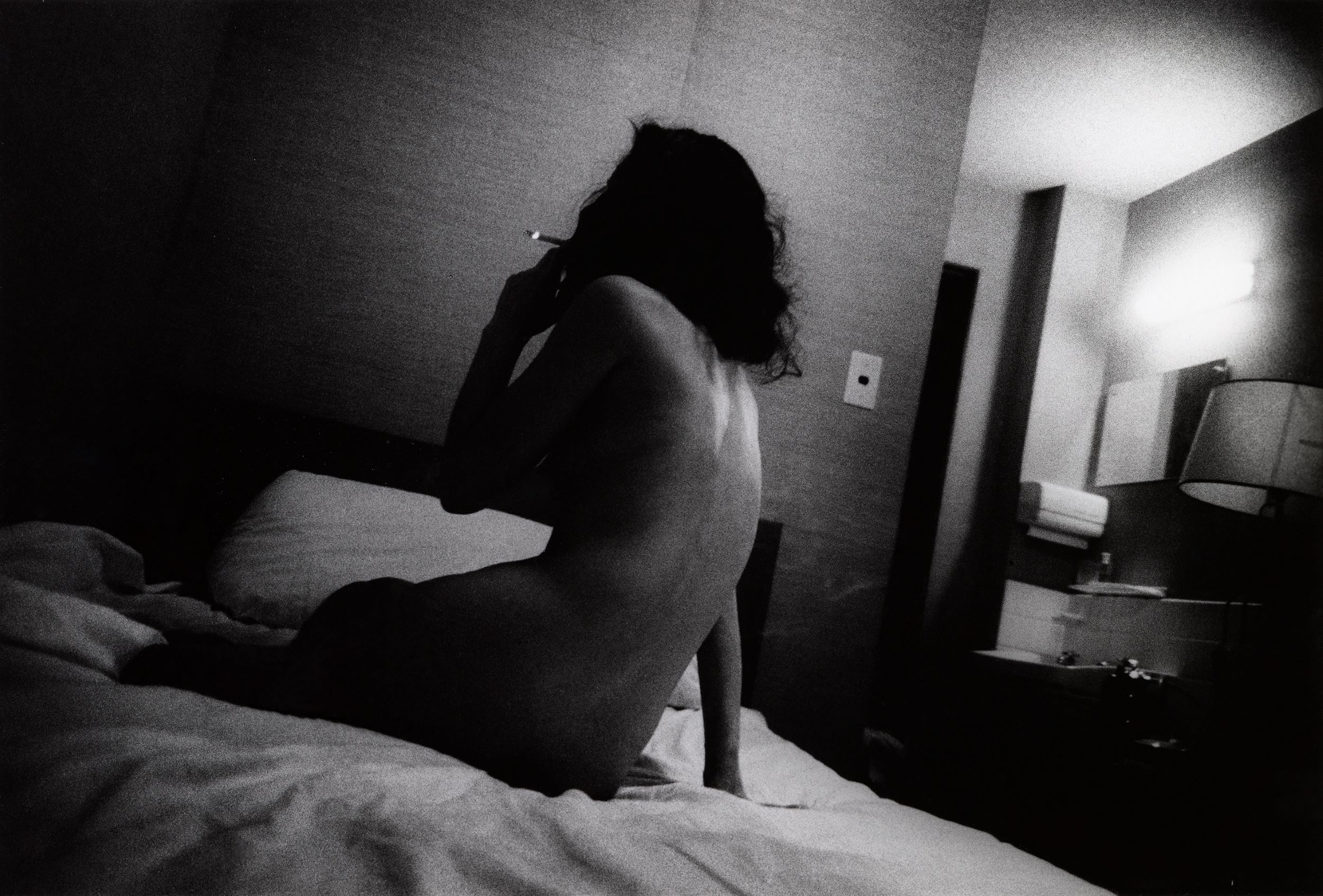

In the 1960s and 70s, he was making extraordinary, beautiful images, capturing Japanese society and this ambiguous feeling towards Westernisation and the erosion of traditional Japanese culture. He was also a very interested in the nature of the language of photography, and all the possibilities that that language could offer. He started to struggle with the idea of photography being a window to the world, and started testing the materiality and the flatness of the image. He worked as a conceptual artist. He was saying, ‘There’s nothing beyond an image, this is just an image’, and to accept that was radically original and beautiful.

But he has continued to move and has become, if anything, more in tune with the times. Since the 1990s he has used a digital camera to make colour photographs, looking at advertisements in shopping malls and beyond. He is interested in the idea that the image is becoming more present in reality, in certain cases even substituting our reality. His work from the 2000s envelops the architecture of the gallery with vinyls, he makes huge patterns of images that go from floor to ceiling. Of course he’s anticipating our lives completely connected to screens, to these multiple virtual realities of the image which are making and in a way eliminating the real world.

Since 2006 he has also published a magazine called Record, where he is photographing every day non-stop, looking at his own neighbourhood and daily life. He’s addressing issues of ego, saying ‘I don’t think artists are more special than anyone else’ and trying to produce something more automatic, and thus democratic. I think he clearly understands that this banality, this horizontality is an essential aspect of photography.

DS: Do certain images have to be included in a Moriyama show? The photograph of the stray dog, for example, is an iconic Moriyama image.

TN: It’s good for the visitor to see some images they recognise because they probably relate to them emotionally, to certain moments in their lives when they first saw them. That creates a lot of connection and affection. Also some images have reappeared in his work over and over and over, they keep being reinserted and renewed with new croppings, new printings, new contrast, new tones. They’re there since the start, and keep following him. But he’s also one of the most prolific photographers ever. So there are plenty of images in the show, and plenty for the visitor to discover.

“What Moriyama is really saying is that it’s in the nature of photography to be reproducible and replicable. He’s against and not interested in the veneration of artworks”