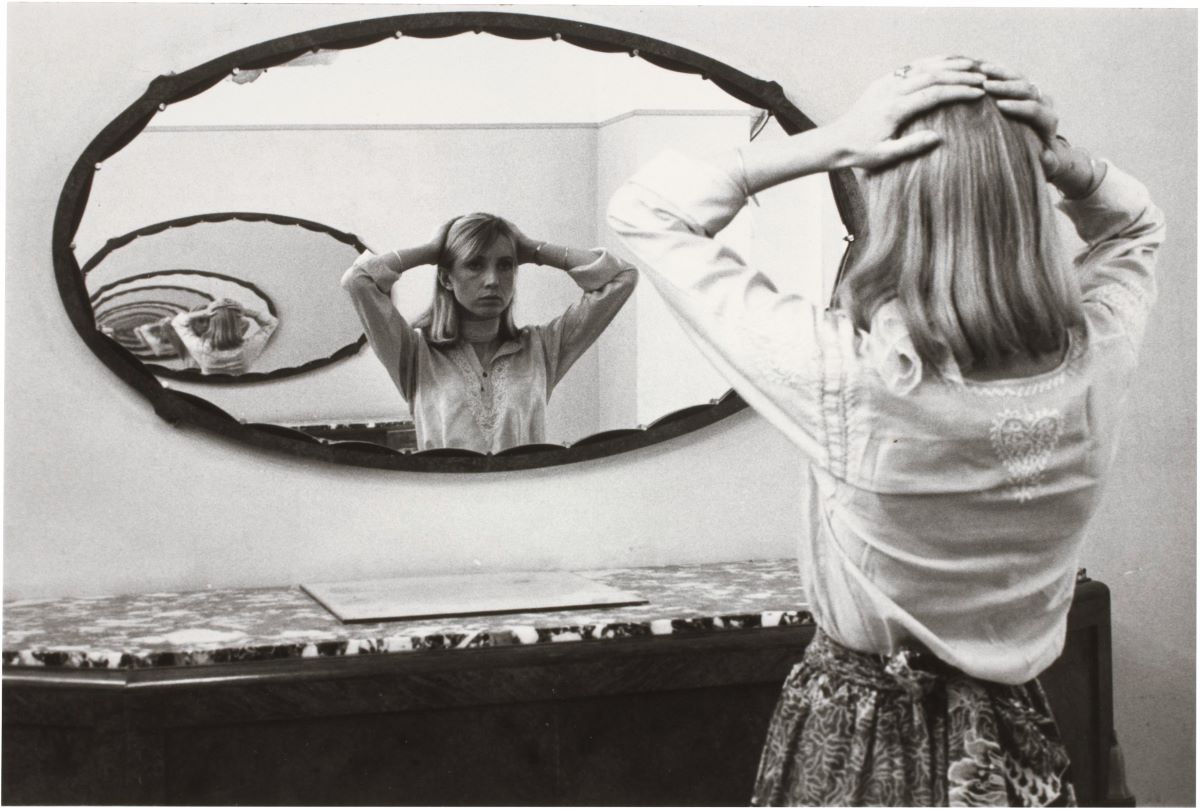

Pierre Zucca. Out 1 by Jacques Rivette, 1970, original print. Courtesy of the Estate of Pierre Zucca

The world’s most prestigious photography festival returns to the south of France this summer. BJP’s editor Diane Smyth reports on the opening week

“There is this assumption around the power of visibility, the idea that people will get justice because they will be seen,” curator Tanvi Mishra tells me at Les Rencontres d’Arles. “But does becoming visible ensure empowerment? I’m not convinced. I’m interested in the simultaneous notion of refusal, that we get to choose not only what (part of us) we show, but also what we refuse to be seen.”

She references Samantha Box, one of the eleven artists she selected for Arles’ Discovery Award this year. An American with African, Indian, Jamaican, and Trinidadian heritage, Box is exhibiting Caribbean Dreams, a series which deals with notions of diaspora and the commodification of identity. One of her images is a self-portrait, restaging a pose colonial photographers forced on young women they considered “exotic.” Box heavily pixellates the image in a deliberate refusal of this depiction. The image, and Mishra’s comment, stayed with me as I visited the exhibitions around Arles, many of which also question the role of the camera.

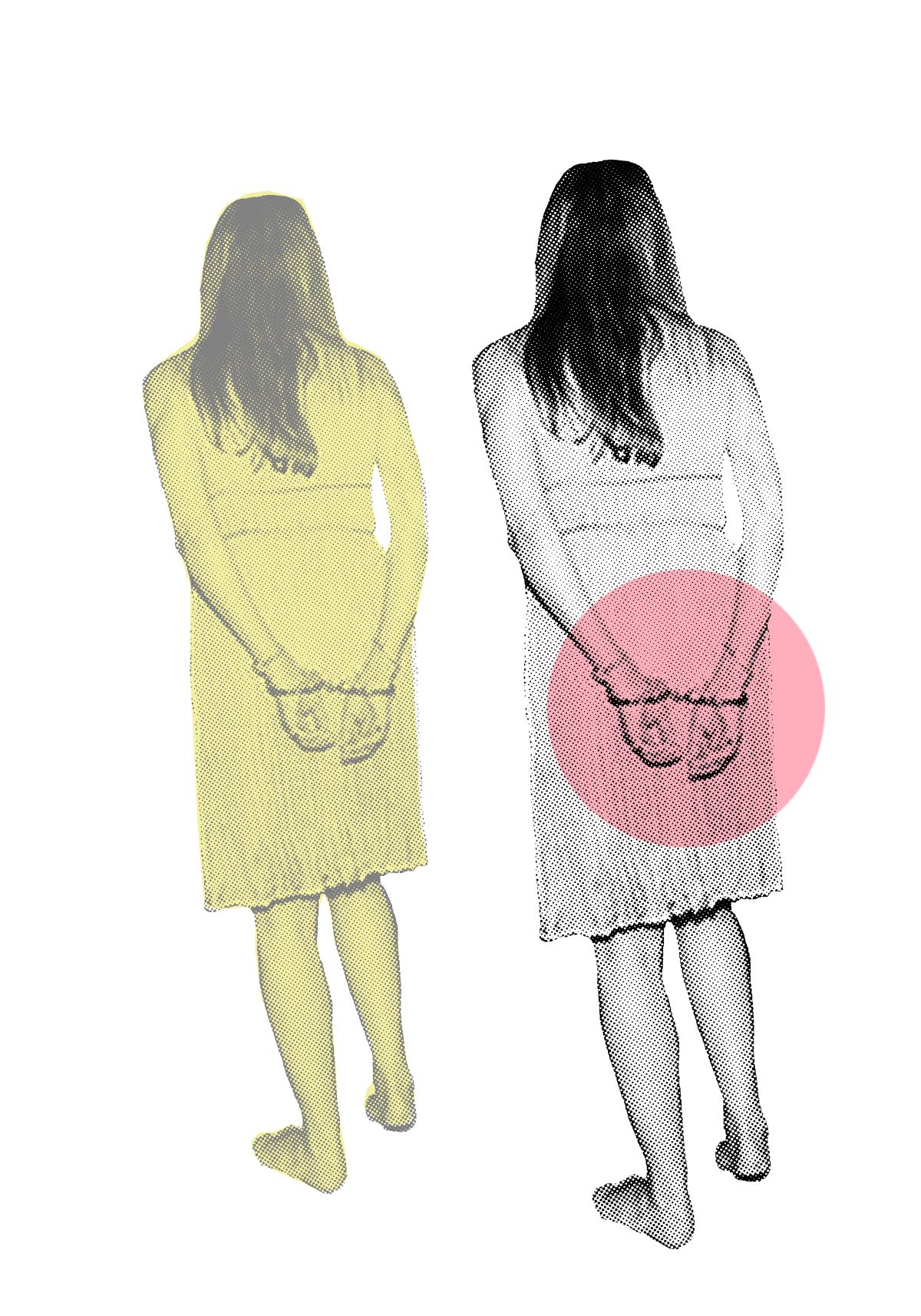

Mishra’s excellent Discovery selection also included Nieves Mingueza’s series One in Three Women, whose title references the fact that one in three women experience gender-based violence. Pervasive yet also hidden, this violence is hard to show without revictimising those affected; Mingueza has responded by taking everyday photographs of women and piercing or covering their heads. She has also reconfigured domestic interiors as crime scenes and everyday objects as weapons and, in her wider series, highlights the sensationalist way in which some magazines restage “true crimes.” In doing so, she uses photography to shed light on a difficult topic, but also reveals some of its flaws. Happy family snaps conceal the reality of domestic violence, while lurid editorials feed off and reinforce misogyny.

Concealed faces

In French “exhibition” translates to “exposition,” and there’s a double meaning in that. Technically it’s the film or sensor that’s exposed, but photographs also expose what (or who) is on view. This thought threw up questions for me in Casa Susanna, an exhibition curated by Isabelle Bonnet and Sophie Hackett in Espace Van Gogh. The show’s roots are in a cache of photographs found in a New York flea market in 2004, and originally made in the 1950s and 60s by a group of crossdressers. The images show the group relaxing and performing in the clothes of the ideal housewife of the time, particularly while holidaying in the home of Susanna and her wife Marie. These pictures were circulated among the community and via a private magazine, Transvestia, delivered directly to their homes.

Bonnet explained to me that she’s found many of those depicted, and got permission to show these photographs; some of the subjects have passed away, but she’s been able to contact their families. Others have proved untraceable. The exhibition doesn’t shy away from tricky gender politics but it’s sympathetic, and Bonnet hopes those depicted would be pleased that they and their community can now be openly shown. It’s a good intention, but on the other hand these images weren’t made for public consumption and were carefully concealed at the time. I too hope those depicted would be pleased.

These questions could be raised about many photographs though, particularly those which are found and recontextualised. I enjoyed the collection of shots of women being arrested in Annika Elisabeth von Hausswolff’s Oh Mother, What Have You Done, on show in the Sosterkap [Sisterhood] exhibition by Nordic women in the Eglise Saint-Anne. But in that case the women’s faces aren’t visible, the exhibition text explains, “to protect their identities, they are shown from behind or have been anonymised in other ways.”

Established masters

Over in the Palais de L’Archeveche, a huge exhibition of work by Saul Leiter shows that similar issues in photography are decades old. Leiter’s work dates back to the 1940s but his offbeat framing, interest in blur and reflection, and sense that some images are covert or even spied, means it still feels edgy. One photograph shot in Harlem in 1966 shows a roughly painted eye and graffiti which reads “The Unseen Eye is Watching You,” a funny but apt take on Leiter’s work.

One aspect that seemed less contemporary was Leiter’s many photographs of seductive women, not so much because they exist but because it’s impossible not to wonder who they all were. Were they girlfriends? Models? Something between the two? The exhibition text doesn’t offer any answers, sticking to a respectful framing of one of photography’s established masters. Perhaps Leiter’s work is due a reappraisal, or at least a more critical view. To be fair to him though, a documentary on view in the exhibition (Tomas Leach’s In No Great Hurry), shows he’s equally wary of this reverence. “I’ve been described as being a pioneer, am I a pioneer?” he drawls. “Maybe I am, maybe I’m not. I don’t mind one way or the other.”

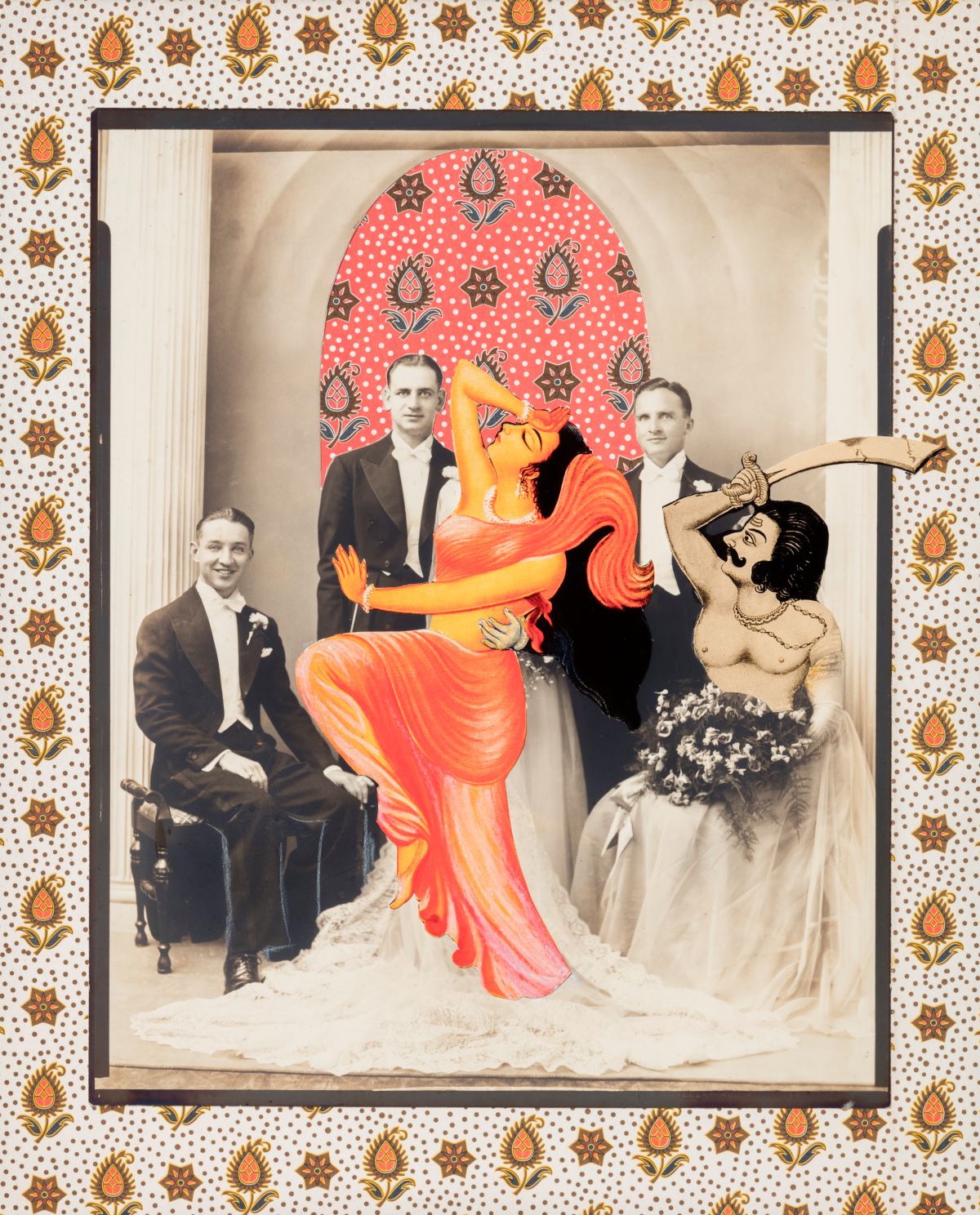

Elsewhere in the Espace Van Gogh, group exhibition Scrapbooks – Inside the Imagination of Filmmakers also suggests questions around photography, the media, what we show, and how. Christian Patterson gathers clippings on a gruesome late-1950s killing spree meted out by Charles Starkweather and Caril Ann Fugate, for example, the same couple who inspired the film Badlands, while Stanley Kubrick mocks up whole fake news stories to be used in The Shining.

Supplementing the camera

Other artists at Les Rencontres d’Arles this year supplement the camera, filling in what it can’t depict. Mathieu Asselin colours in maps and images to depict the pollution caused by Fibre Excellence, a paper pulp manufacturer based ten miles from Arles, for example, while in the Associated programme, Celine Clanet’s Ground Noise includes microscopic images of insects, the kind of work more usually found in scientific journals. A thought-provoking look at a key topic, as pollution and climate change wreak havoc on the insect population, Clanet’s show was a personal favourite.

Another exhibition in the Associated programme, Grow Up, is a large group show on ecology in the Fondation Manuel Rivera-Ortiz, which includes series around climate change and cocaine-trafficking. The exhibition included a favourite installation, Antoine Renard’s Crypto-Pharmacopoeia, which uses pixelation, moving-image, sound and even smell to give a flavour of that which photography can’t capture. “This project continues my research into the way in which plants exert an influence on the psychic construction and human identity,” Renard’s text reads.

Festival director Christoph Wiesner told me that Les Rencontres d’Arles is an opportunity to see where photography and society are at in any given year. The current theme is A State of Consciousness, and the festival blurb states that “awareness – at the very least – of climate change has become unavoidable, directly affecting our habits.” For me, State of Consciousness also encompasses a contemporary interest in photography – a cool look at what the medium can and can’t do at a time when we’re realising the flaws in many narratives and perspectives. This strand runs through the exhibition Insolare, for example, a series of images made in the local Camargue landscape by Eva Nielsen. Each image includes multiple layers: those seen in the landscape resulting from human use of it, and layers Nielsen has added through collage, printing and rephotographing images on fabric.

Money talk

BMW took me and other journalists into the Camargue to see some of the places Nielsen photographed – the company is one of Les Rencontres d’Arles’ partners, along with the SNCF national railway, Kering luxury group and LUMA arts organisation. BMW brought a fleet of electric vehicles to the festival and one of them, the i7, features a windscreen on which a map and elements of the dashboard are projected over the view. I got thinking about the augmented reality seeping into our lives, the fact that artists are becoming more interested in images as they increasingly penetrate into our lives. It’s a topic picked up in the Fisheye Immersive exhibition Habeas Corpus, which argues that our bodies are now both physical and 3D. (The young journalists I was with were underwhelmed by this show, arguing that filters and “digital makeup” are no different to Instagram).

Les Rencontres d’Arles is 15 per cent funded by sponsorship, 55 per cent ticket sales, and 30 per cent from the French government and public funds. Wiesner is upbeat about the perhaps surprising level of state funding, commenting that while it makes for “fragility,” it also means the festival has freedom. Becoming more conscious of what the medium can do includes becoming more conscious about the festival’s own role. Les Rencontres d’Arles has been a member of the Collectif des Festivals Éco-responsables et Solidaires since 2022, meaning it’s committed to minimising its environmental impact, and the historic venues also have to be handled carefully. Nielsen is showing her images on a metal construction, for example, so that they’re not hung on the cloister walls.

The funding model means ticket sales are important to the festival, because the number of tickets sold one year directly impacts the following edition’s production budget. The exhibitions are free for locals, and Les Rencontres d’Arles has run a professional integration and training scheme for the last 30 years, giving long-term unemployed locals work both before and during the events. This scheme has a measurable impact, with some 70 per cent of participants going on to find further employment afterwards, and it’s an interesting intervention because Arles as a whole isn’t rich. In fact, some 24 per cent of the local population lives below the poverty line, and 59 per cent don’t earn enough to pay tax.

In some ways the city is changing, Wiesner says, noting that “there are more wealthy people living here.” The festival doesn’t need to add more exhibitions, he says, as there are now private institutions showing work. LUMA Arles houses the billionaire heiress Maja Hoffmann’s LUMA Foundation, for example, opening in 2021 in a Frank Gehry-designed building and wider ‘campus’. There’s also the Fondation Vincent Van Gogh Arles (where Hoffmann is president), and the just-opened Lee Ufan Arles, which is dedicated to the minimalist artist’s work. LUMA is hosting two exhibitions on the main programme: Gregory Crewdson’s Eveningside – 2021-2022, and Rosangela Renno’s On the Ruins of Photography, both interesting meditations on the medium.

“But does becoming visible ensure empowerment? I’m not convinced”

Arbus revisited

LUMA Arles hosts other shows too, two of which were attracting a buzz – Constellation by Diane Arbus, and The Shape of Things by Carrie Mae Weems. Both are undeniably impressive in terms of quality and installation, but for me also suggested questions around context and place. Constellation displays new prints of Arbus’ entire oeuvre by Neil Selkirk, her former student and the only person permitted to print from her negatives since her death. The images are freely mixed on a metal structure, discrete projects and series dispersed with little information provided beyond a large book of captions.

I found this installation both refreshing and troubling. On the one hand, it’s great to see images presented on their own terms, not illustrating heavy-handed theses or exhibition texts. On the other, some of Arbus’ work has been controversial, not least because of her comments on photographing “freaks.” Does decontextualising this work sidestep difficult questions? I was intrigued by the use of mirrors, though, which are attached to the back of each framed print; most prints are hung back-to-back but occasionally they aren’t, visitors are brought face-to-face with themselves, on display like so many others.

Weems’ The Shape of Things was the hot tip for many, a powerful and affecting multimedia show which includes Cylcorama: The Shape of Things (2021), a 40-minute, seven-part film of US history past and very recent projected onto a huge cylindrical screen. The exhibition also includes Family Pictures and Stories 1978-1984, a more intimate work about everyday life for Weems’ own friends and relatives. I particularly liked these works plus Painting the Town (2021), images of hoardings put up in anticipation of riots, and a whole room centring round the Black Panthers, including portraits of key players and an installation on its community work.

These last two gave me pause for thought though because, while Weems’ work obviously deserves a fantastic installation and venue, the kind of radical social change the Black Panthers envisaged seems pretty far from a foundation set up by a billionaire. From this perspective, I thought one of the most interesting exhibitions in Arles is the mid-career retrospective by Palestinian photographer Ahlam Shibli, also on show at LUMA. Titled Dissonant Belonging, it collects work focusing on “unrecognised perspectives” such as the community built by children in a Polish orphanage, or the underground market set up by migrants in Turin. It also features a commission shot in Arles.

A huge body of work, this features images taken in the Griffeuille, “a more disadvantaged neighbourhood of people from different origins, which is separated from the LUMA campus by the tracks of the Arles-Marseilles railroad”, along with shots of Hoffmann herself and portraits of the LUMA curators. This work is firmly situated in the city, showing some of its contrasts and contradictions – and the role of art in them. There are images at home with Francoise Nyssen, for example, the former French Minister of Culture and daughter of the Actes Sud publishing house founder. A coolly sociological caption explains: “In these pictures, recalling still images from a film, class-specific behaviours are enacted and suspended.”

Local action

If it’s interesting to think about art’s role in Arles, it’s worth returning to Here Near, the show by Mathieu Asselin plus Tanja Engel and Sheng-Wen Lo. All three have made work in the local area, researching how the Anthropocene can be found in its ecosystem; Lo’s work is a kind of treasure hunt based around roadkill (which may or may not have been mown down by BMWs). The exhibition is shown above the Monoprix supermarket alongside Optical Theater, photographs by Pierre Zucca arranged by curator Aurelien Froment, which includes Zucca’s cult film stills and shots of yoga sequences, plus his images for The Living Currency.

First published in France in 1970, Pierre Klossowski’s La Monnaie vivante analyses commodification and private desire, influencing theorists such as Michel Foucault and Deleuze & Guattari and relevant all over again with the resurgence of autofiction, commodification and anticapitalism. I found this show surprisingly intense, and walking back out through the supermarket was a trip, the products arranged like prints on the wall, the price labels so much like captions.

As a security guard checked my bag at the exit, I thought of another Monoprix in nearby Marseilles, from which a 28-year-old took a can of Red Bull during one of the many recent protests over the killing of Nahel M. Nahel was a 17-year-old of Algerian descent, shot by the police on the outskirts of Paris. For taking the Red Bull, the 28-year-old was sentenced to ten months in jail. Can photography and photography festivals pave the way for radical change, or are they just another layer of distraction? The answer, I suppose, is both.

The exhibitions at Les Rencontres d’Arles are open until 24 September. Check the LUMA Arles website for more information about its exhibitions.