All images © Mathieu Asselin

This article first appeared in the Money+Power issue of British Journal of Photography. Sign up for an 1854 subscription to receive the magazine directly to your door.

Renowned for his photographic investigations, Mathieu Asselin now turns his lens on Dieselgate, revealing the car industry’s violent and exploitative relationship with nature

“Now let me ask you a question,” says Mathieu Asselin. He glares into his webcam. “Do you ever find yourself in a traffic jam looking around you? All these solitary people are sitting in this huge piece of metal with two sofas and five kilometres of wire inside. It is completely crazy, it is bullshit.” We are talking about his upcoming project, True Colors, which explores the automotive industry’s “violent” relationship with nature. It is not the first time that Asselin, whose investigative documentary photography seeks to “challenge the corporate status quo”, has become irate during our conversation. ‘Bullshit’ appears to be his favourite word.

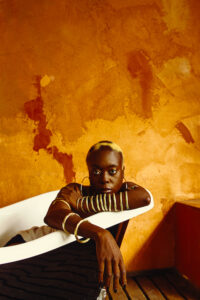

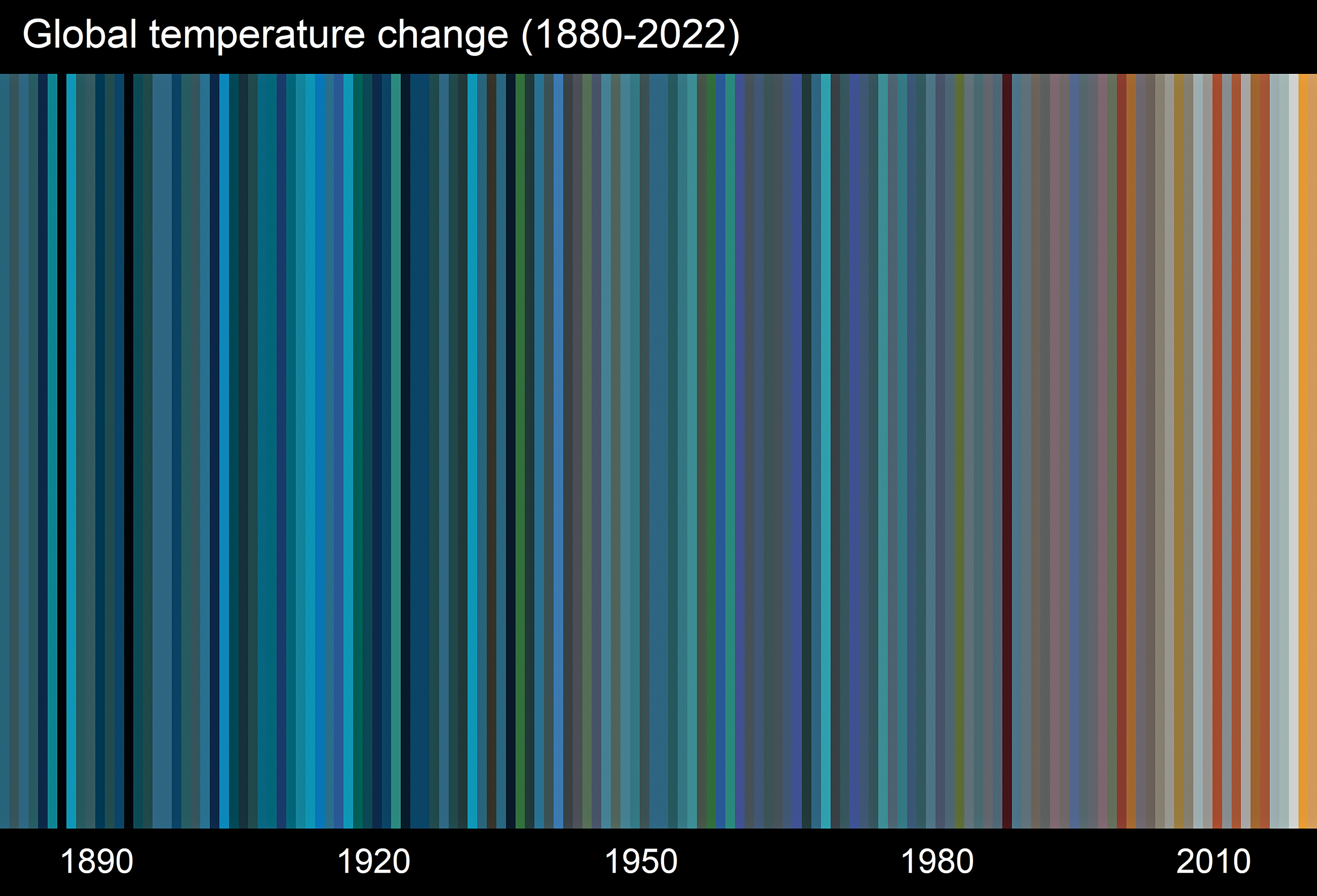

The work is comparatively serene: a colourful series of idyllic natural vistas lifted from car sales brochures. “They use the landscape to sell these cars,” explains the French-Venezuelan artist, whose intention is to show how “embedded” pollutants have become in nature. These lifted landscapes are silkscreen printed on 100×150cm steel plates with ink extracted from diesel vehicle exhaust pipes. Then they are washed out in automotive paints – colours that are incidentally named after valuable ecosystems. A pine tree lake is bathed in Volkswagen’s ‘Montana Green’; a pristine mountain top is quilted in Renault’s ‘Glacier Blue’ [page 139]; a desert is baked in BMW’s ‘Arizona Sun’. Working with a biologist, Asselin pulled 257 of these colours and created a graphic that illustrates the warming climate from 1880 to 2022 [pages 132–133]. ‘Alaska Blue’ falls somewhere in the Victorian age, while ‘Amazonia Green’ is in the mid 20th century. The more alarming ‘Coral Red’ is near the present day.

Asselin will show the plates at an exhibition at the Ravestijn Gallery in Amsterdam in September, alongside publishing a photobook. “At the top of all this is the relationship between cars and the landscape. Cars have been one of the biggest factors in shaping the world around us,” Asselin says. “They not only affect it in terms of global warming, but also with roads. There is virtually no place in the world where you cannot see something related to the automotive industry.”

In 2015, US environmental regulators got a tip-off. Volkswagen was fitting software to its cars to cheat emissions tests. Vehicles fitted with these so-called ‘defeat devices’ churned out less toxic nitrogen oxide (NOx) under laboratory conditions than on the road. The case was christened ‘Dieselgate’. It swiftly escalated into one of the costliest corporate scandals in history. Almost all diesel cars that rolled off VW production lines between 2009 and 2015 – 11 million of them – were implicated. Audi, BMW, Renault, Fiat, Mercedes and others later admitted to lying in a similar way. A 2016 study found an eye-watering 97 per cent of all modern diesels emitted more NOx than the official limit. In other words: the cheating was systemic.

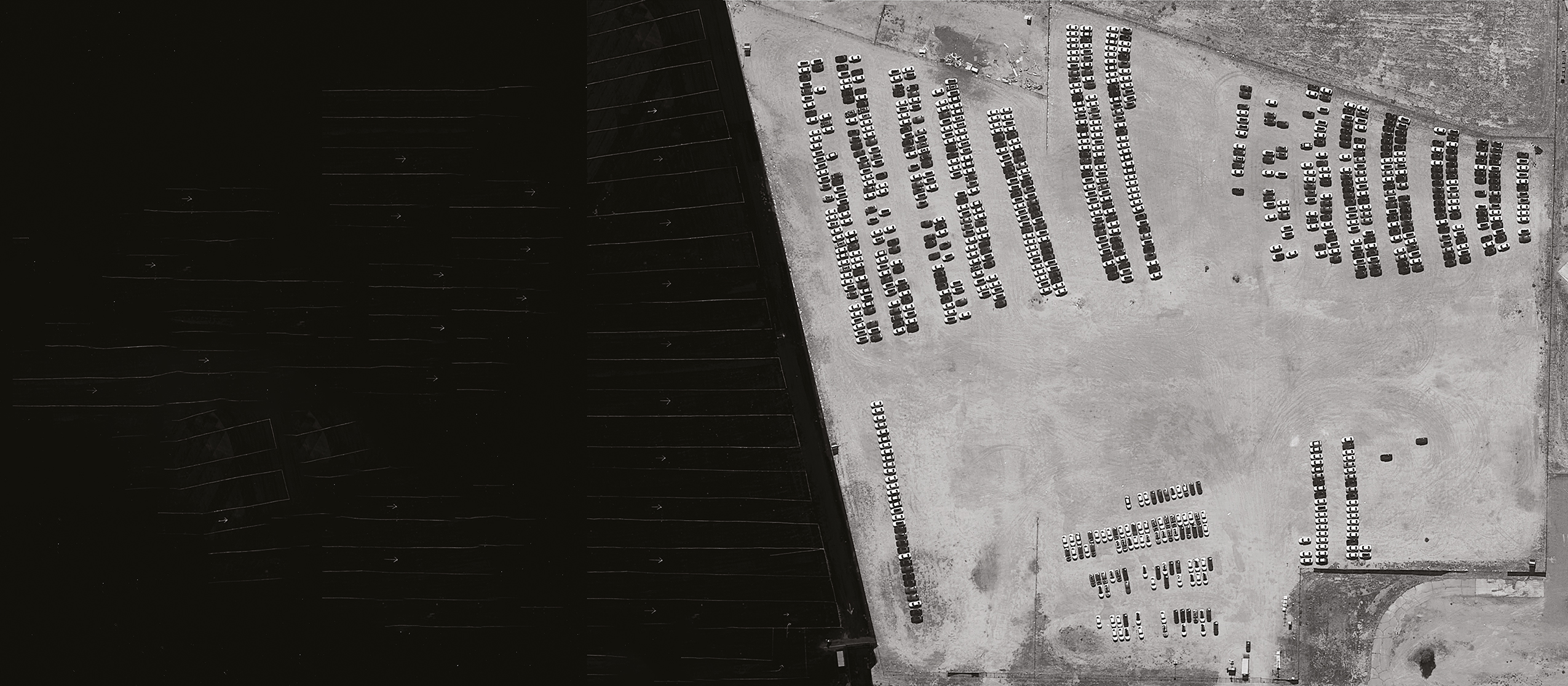

Asselin takes a bird’s-eye view on the scandal. True Colors’ second segment is filled with satellite images of decommissioned Dieselgate cars parked in “graveyards” across the US. The vehicles sit in their tens of thousands with a farm, a nuclear power station and an airport for scale. He assembles them in collages [pages 134–137] next to tiny circuit boards that housed the ‘defeat devices’. Pins, electrical grids and serial numbers are so small that they had to be captured with specialist cameras. These circuits echo the grids of cars pictured in the humongous car parks: “I liked the idea that such a small thing as this computer board can lead to thousands of cars parked in an airport.”

“Commercials and propaganda are the most powerful tools these companies have to make their status quo live as long as possible. We need to stop the bullshit”

Volkswagen has paid £26billion in legal fees and payouts to customers, but few people have gone to prison. Martin Winterkorn, the chief executive at the time, faces charges of fraud and stock market manipulation. He has not been sentenced. Former head of development Heinz-Jakob Neusser is in a similar situation. One lowerranking executive, Oliver Schmidt, is already out of jail. He served less than four years inside. Asselin’s project includes scans of arrest warrants for Winterkorn, Neusser and others, issued in 2017 by Interpol, the international policing organisation. The men are wanted in the US, but Germany rarely extradites its citizens to countries outside Europe. Schmidt went to prison because he was arrested at Miami airport trying to flee the US.

The photographer says the documents “show the gravity” of the situation. It is rare that a top CEO becomes a fugitive of justice. Asselin spent three years researching True Colors, and wants to make sure people do not dismiss it as the ideas of a “leftist, long-haired” artist. (The 49-year-old has a beard and a resplendent ponytail.) But on a more basic level, Asselin just wants you to know who to blame. He says too many documentary photographers “trade in subtext”, while he prefers a more direct method using company names and specific information. “Of course we as artists need to use aesthetics, and [those are] fundamental to trigger reflection in people… But do they really highlight the complexity of the issue? I don’t think so.”

This matter is sometimes complicated by corporations like HSBC, Pictet and Carmignac sponsoring awards. Every year, BMW gives an artist €10,000 for its arts patronage programme. Asselin applied for the 2023 edition, seeking to explore “the connection between their cars and the environmental issues we face today”. He stresses that the competition was “fierce”, and does not question the integrity of the jury: “However, my proposal didn’t fly.” He had better luck with his 2017 project, Monsanto: A Photographic Investigation, which focused on the US chemicals manufacturer Monsanto. It won the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation First PhotoBook Award, and was shortlisted for the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize. The project showed contaminated sites in Anniston, Alabama, where Monsanto had a factory, and portraits of the town’s residents. Many are sick from the toxic water. Others grieve relatives who died of chemical exposure. In one image, the nearby Choccolocco Creek runs red.

Now, the car industry is going electric. Volkswagen’s current CEO Thomas Schäfer recently said its new cars would all be “zero emissions” in a decade. The European Union recently agreed to ban the sale of petrol and diesel cars from 2035. Karima Delli, president of the EU’s transport committee, hailed it “a historic vote” and “a victory for our planet and our populations”. Asselin is not so sure. “Calling something ‘zero emissions’ is a very colonialist take,” he says, pointing to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where hundreds of thousands of Congolese people mine for cobalt used in electric car batteries, often on poverty wages and under brutal working conditions. In his 2023 book Cobalt Red, Harvard academic Siddharth Kara says it amounts to modern-day slavery.

In Chile, the majestic Atacama Desert is being dug up for lithium, another important component. This uses vast amounts of water in an already parched landscape. The Natural Resources Defense Council, a charity, reports that this causes severe ecological damage, and is “violating” Indigenous communities. Both cobalt and lithium mining are, of course, heavy on carbon emissions.

Asselin does not provide a solution. That is not the point – besides, who can? He even stresses that cars are an important part of modern life if used sparingly. He drives, but does not own a vehicle. “This is not a work against cars,” he says. Instead, his aim is to expose greenwashing and its exponents. Automotive industry bosses take the world’s great ecosystems and repackage them in glossy brochures to shift units. At the same time, they carve those landscapes up and cheat emissions tests with near impunity. “Commercials and propaganda are the most powerful tools these companies have to make their status quo live as long as possible,” he says. “We need to stop the bullshit.”