All images © Henry Agudelo

This article first appeared in the Money+Power issue of British Journal of Photography. Sign up for an 1854 subscription to receive the magazine directly to your door.

Content Warning: This article contains imagery that readers may find upsetting

The veteran photojournalist has captured the wonders and horrors of Medellín for over 40 years. Here he reflects on documenting the conflict that continues to haunt the city

At around 10pm on an autumn evening in 1996, Henry Agudelo left the offices of Bogotá-based newspaper El Tiempo. Turning the corner, a sense of fear gripped him. Two cars rolled up beside the pavement in the dark, and he was bundled, hands bound, into the boot of a vehicle.

Over the course of several hours, the car and his kidnappers stopped at numerous ATMs. Each time they withdrew money from his credit card, he prayed he would be let off the torturous merry-go-round. Eventually, he was dumped at a bus stop. A week later, he discovered that the danger of being a photojournalist in 1990s Colombia was not just due to the threat of the country’s warring political groups – his kidnapping ordeal had been the work of a territorial colleague, bitter that Agudelo was earning more on assignments.

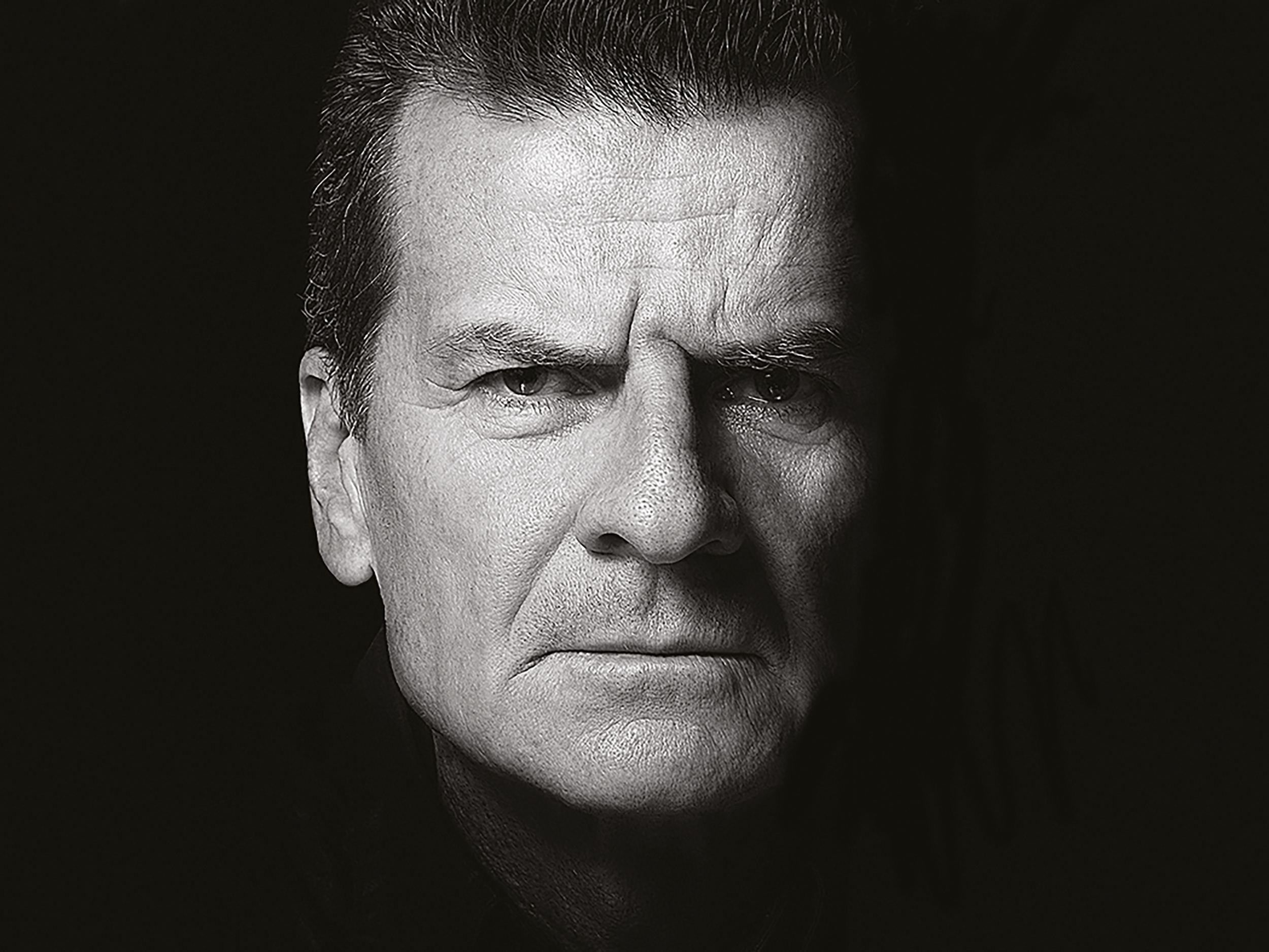

The 63-year-old photographer speaks without sentimentality, but his stories of the past have an audible weight. One of Colombia’s pre-eminent photojournalists, he has captured both the wonders and the horror of humanity within the country, leading journalist Robinson Usuga Henao to call him the ‘El ojo De Dios’ (the eye of god). It is a testament to the depth and breadth of his archive, much of which remains unpublished due to years of journalistic censorship.

Born in the poverty-stricken El Pesebre barrio in Medellín, Agudelo’s family had fled ‘La Violencia’, the period of civil-war between the 1940s and 60s which was largely fought in rural areas and pushed people into the city’s margins. It was a job opportunity as a darkroom technician at El Mundo, the first of the national newspapers Agudelo would work at, which gave him a route out. Interested in photography, he had asked to shadow senior reporter Pedro Nel Ospina at football matches and began involving himself, picking up commissions that others didn’t want to accept. In the late-80s, the news was dominated by Pablo Escobar and the drug-trade violence which was rapidly engulfing the city, with the ill-fated Comuna 13 district becoming a transit route for trafficking. But as a self-titled ‘peasant boy,’ Agudelo’s competitiveness within an elitist industry increasingly pushed him to find those difficult-to-capture images.

Agudelo’s early photographs document the horror of Escobar’s unhinged temper, opposed factions of rightwing paramilitaries (funded by wealthy landowners and businesses), radical leftist guerilla groups, and the chaos of government. The violence killed thousands of innocent people, not to mention the ‘disappeared,’ throughout the 1970s to 1990s. His archive includes photographs of young military personnel filling in to placate the 1985 attack on the Supreme Court of Colombia, in which members of the leftist M-19 guerrilla group took over the Palace of Justice in Bogotá. Another series documents the horror of the Mapiripán massacre of 1997. Agudelo arrived as charred bodies still smouldered. Paramilitaries had terrorised the village and executed ‘presumed’ guerillas, children among them.

The faces of violence

Photographing these scenes shaped Agudelo’s visual language. “I felt a terrible anxiety to achieve a single photograph that could reveal the scale of the drama that had taken place,” he says. “I wanted an image so powerful it competed with the text [in the newspaper].” His earlier photographs often honed in on the human faces of tragedy, an intense focus on pain and suffering. The camera gave him a licence to be there. “I appeared on the scene without being the protagonist of it,” he says. Shooting on an analogue 35mm, he was forced to think more; to be precious with his film.

Agudelo still follows the legacy of the conflict today. From his son’s bedroom he can see Comuna 13, where he grew up. The neighbourhood was a guerilla stronghold until 2002’s Operation Orion – a military offensive that with the ostensible aim of removing rebels groups, but which also saw the death and forcible disappearance of civilians in the area. Just a few miles away is a great scar in the hills that marks La Escombrera. The landfill is thought to be a mass grave for over 300 people who vanished during the military attack. Agudelo’s work is concerned with filling in those silences and searching for justice, using his northern star ‘hacer visible lo invisible’ (to make the invisible visible) as a guide.

In one photograph, a small boy peers from behind a photograph of his missing father, a policeman presumed killed by Colombia’s largest rebel group, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in 1993. The portrait captures the child’s faith in the image, all images, to prevent collective memory being extinguished. The family had joined a social movement, La Asociación Caminos de Esperanza Madres de La Candelaria, which holds a vigil every Wednesday at a church for victims of the conflict. Agudelo keeps in close contact with his subjects, whose lives he feels a great affinity towards.

“I see more and more of a country immersed and enclosed in a few who want to exploit us socially, economically, politically. I see the young people of Colombia without a future”

A few years ago he heard news that the once little boy had lost himself within the folds of a criminal gang, never knowing the fate of his long-lost parent. When something is too overwhelming to remember, as humans our tendency can be to try to forget. “In Medellín, we like to forget, or even have to forget,” he says, “because it is a matter of survival.” A photograph, for Agudelo, is a fight against oblivion.

His series Indelible Marks (2017) is an example of this mission to memorialise. Working with a morgue, Agudelo photographs portions of skin of unknown deceased. He records their prominent features – such as tattoos and scars; marks that announce the individual despite the anonymity of death – so that their remains might one day be named. With a bittersweet happiness, Agudelo recounts how one photograph helped the family of a vanished transgender sex worker to identify their remains years later. Harrowing but compelling, the series continues to illustrate the painstaking journey of collective healing.

The conflict in Colombia is ongoing. It still stirs in Afro-Colombian region Chocó, where cocaine production is rapidly increasing, and in southern states near Bogotá. In January 2023, the government’s human rights ombudsman revealed that 215 activists and social leaders were killed across the country in 2022 – the highest toll ever recorded.

“I see more and more of a country immersed and enclosed in a few who want to exploit us socially, economically, politically,” Agudelo says, sadly. “I see the young people of our country without a future.” According to Agudelo, many Colombian photojournalists have not kept their archives, appalled by the memories they hold. But Agudelo has chosen to hold on to his. “My legacy to young people today is that they identify themselves with what was done in the past,” he says, “and know there is still a way to solve all this.”