All images © Werner Bischof

The Swiss Magnum member is best known for his post-war photojournalism, but an unearthed archive of colour work may change and enrich his legacy. Rosalind Jana picks over Bischof’s new shades

Werner Bischof’s black-and-white photos reveal a sharp eye for texture and silhouette, and an acute sensitivity for a telling moment, no matter how devastating or surreal. The Swiss photographer and early Magnum member is best known for his post-war photojournalism, first in Europe and then further afield. By turns stark and hopeful, his images illuminated a changed world: the onward motion of daily life caught against a vast backdrop of destruction and renewal.

“Werner Bischof was always considered a classical black-and-white photographer of the 20th century,” explains the artist’s son, curator and director Marco Bischof. We are standing in the MASI Lugano, a graceful slab of a building overlooking Switzerland’s Lake Lugano. The museum is currently host to an exhibition titled Werner Bischof: Unseen Colour. Previously known for his monochrome work, recently Bischof’s archives have yielded a treasure trove of brightly-hued photographs – around a hundred of which are on display. “Now, with these pictures we have to reorientate the compass,” says Marco.

It was Marco who found the colour work. His father died when Marco was only four, in a tragic car accident in Peru in 1954, but left behind a vast archive. Several years ago Marco opened some boxes of glass-plate negatives, which revealed an entirely different side to Bischof’s work. They were shot using a Devin Tri-Color camera, a then-cutting-edge piece of technology that exposed three black-and-white glass negatives together.

Each had a different colour filter (red, green, and blue) which, when developed together in the dark room, yielded detailed and colourful images. The process later fell out of use but Marco worked with a team of processing specialists to scan and print these images, sometimes working on a particular shot up to twenty times to get the tones right.

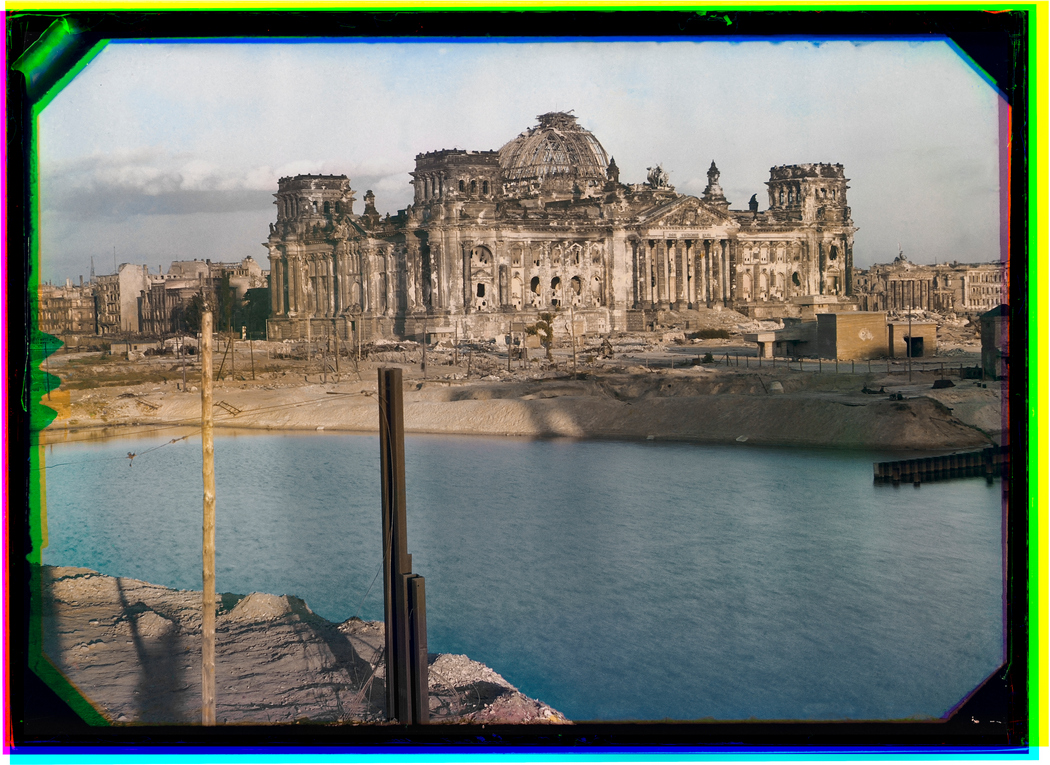

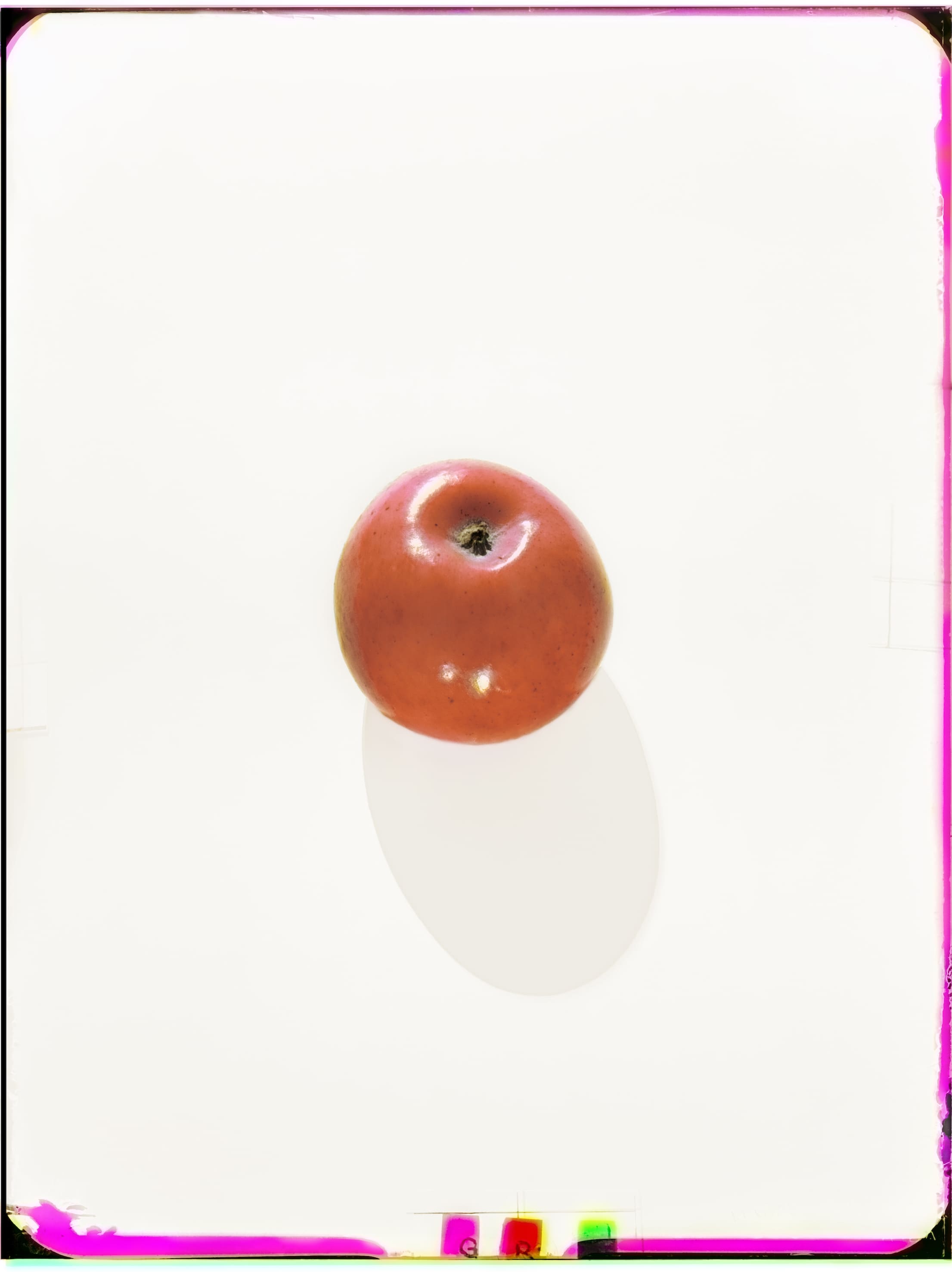

The Devin had been lent to Bischof by Zurich publishers Conzett & Huber and, during the Second World War, Bischof experimented with it in his studio, creating dreamlike images. In one photograph saturated tentacles of dye move through water, in another the whiskers on a white cat stand in sharp relief. One nude, reminiscent of Erwin Blumenfeld’s work, becomes a kaleidoscope of colour and shadow. When the war ended, Bischof took the camera with him as he travelled across Europe, capturing the aftermath of the battle and deprivation with this bulky piece of kit.

“Fellow Magnum member Henri Cartier-Bresson once famously declared, ‘Photography in colour? It is something indigestible, the negation of all photography’s three-dimensional values’”

The photographs he shot with the Devin were largely destined for Du magazine, which Conzett & Huber used as a vehicle to demonstrate the power and possibilities of colour photography. Colour remained an unpopular choice, particularly among those who considered themselves serious photographers.

This was partly for practical reasons. Colour was harder to process and more expensive to print, both barriers in the fast-moving world of photojournalism. Colour also had a larger margin for error, the shades quickly tipping from realistic to garish. Added to that, cameras such as the Devin were large and heavy. Hauling them up onto a rooftop to capture a bird’s eye view of a destroyed bridge required a certain kind of grit.

For all these reasons colour was often relegated to the commercial realm, where other, more value-driven interpretations came into play. Colour was thought to be lacking in substance, better used to advertise things than reveal truths about them. These suspicions lingered for years. Fellow Magnum member Henri Cartier-Bresson once famously declared, “Photography in colour? It is something indigestible, the negation of all photography’s three-dimensional values”. As late as 1969, Walker Evans decried its vulgarity, writing “colour tends to corrupt photography and absolute colour corrupts it absolutely”. Even in 1980, theorist Roland Barthes expressed his reservations in Camera Lucida, calling it “an artifice, a cosmetic (like the kind used to paint corpses)”.

Looking at Bischof’s photographs suggests a different reading altogether. Black-and-white can distil, but it can also obscure or underplay. There is a new kind of awe and horror in viewing abandoned villages and gutted cities in vivid colour. Far from insubstantial, these photographs work to bridge a potential empathy gap. Everything feels more proximate: fabrics, farmyards, burnt out buildings, the grey and pink facial scars of a Dutch boy injured by a German booby-trap (Bischof’s diary noted “blue-violet burn marks from the shrapnel, a glass eye and a red mask”).

Colour brings an immediate recognition, conjuring a past that feels startlingly close.“It gives you a whole different feeling… a directness,” Marco Bischof says. “For example, the Reichstag is the most overwhelming. It looks like a monster.”

Werner Bischof: Unseen Colour is structured around three cameras Bischof used – the Devin Tri-Color, then a Rolleiflex, and a Leica. Each section reveals the ways in which technology inflects images. The Devin brings a larger-than-life precision, but its long exposure times weren’t suited to motion. Hands blur, and a man walking down the street becomes a fuzzy outline against tightly delineated bricks. People pose with an almost Victorian stiffness while the shutter slowly blinks.

The Rolleiflex 6×6 was softer but allowed for more spontaneous work, especially as Bischof’s travels expanded across Europe and into Asia, where he produced acclaimed reportage in India and Korea. In Japan, he found such a deep aesthetic affinity that he stayed for a year. The Leica was lightweight, crisp and reactive, his time in North and South America documented with refreshed emphasis on the play between colour, light and line. “He wanted to become a painter, and for a painter, colour is absolutely essential,” Marco adds.

The breadth of work testifies to Bischof’s restlessness as a photographer, his onward urge to expand the boundaries of his medium while refining his vision. The Devin photos are being shown uncropped, the coloured edges of their scans still visible. It is a fitting curatorial decision, revealing the layers of work that went into their creation and printing. Looking at them perhaps evokes the famous moment in The Wizard of Oz when everything flushes with technicolour, a door opening onto another world. But where Oz is a place of “artifice” (to return to Barthes), these images offer a fresh perspective and a direct glimpse into the past, revived in shocking colour.

Werner Bischof, Unseen Colour, is at Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana, Lugano, until 16 July