From the series miss fotojapón, 1998-2022, by Juan Pablo Echeverri

Identidad Perdida [‘Lost Identity’] is a new show devoted to the work of Juan Pablo Echeverri, a Colombian artist who died suddenly last year of malaria.

Curated by Wolfgang Tillmans with some of Echeverri’s closest friends and family, it’s now open at Tillmans’ Between Bridges gallery in Berlin and is coming soon to the James Fuentes gallery in New York. The two-site exhibition gathers work made by Echeverri over the last three decades, and is both a tribute to the artist and a chance to get his work more widely seen – work that, says Tillmans, still hasn’t received its due. “In retrospect it has become clearer how important his work was, and how trailblazing,” he comments.

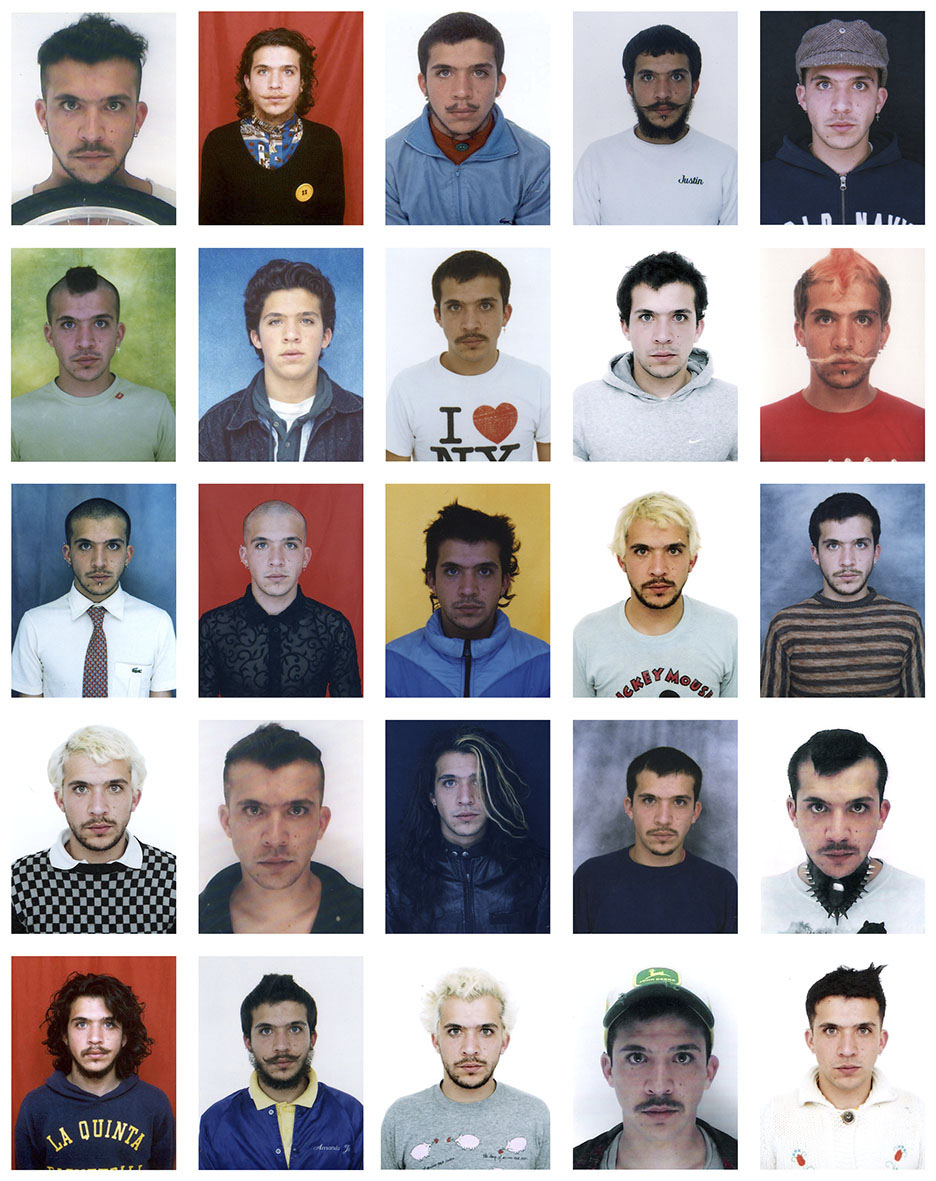

Tillmans met Echeverri by chance 10 years ago while preparing a solo show for la red cultural del Banco de la Republica en Colombia. One of Tillmans’ usual assistants couldn’t travel to Bogotá and recommended Echeverri in his place; the Colombian quickly became one of Tillmans’ friends, and part of his regular travelling team. Echeverri had already been working on one of his key series for over a decade when Tillmans encountered him. Titled miss fotojapón, it’s a collection of more than 8000 self-portraits taken every day in passport booths between 1998 and 2022.

“A passport photo is really a very crude approximation of our complex selves”

miss fotojapon (1m x 1m #3) 1998-2022

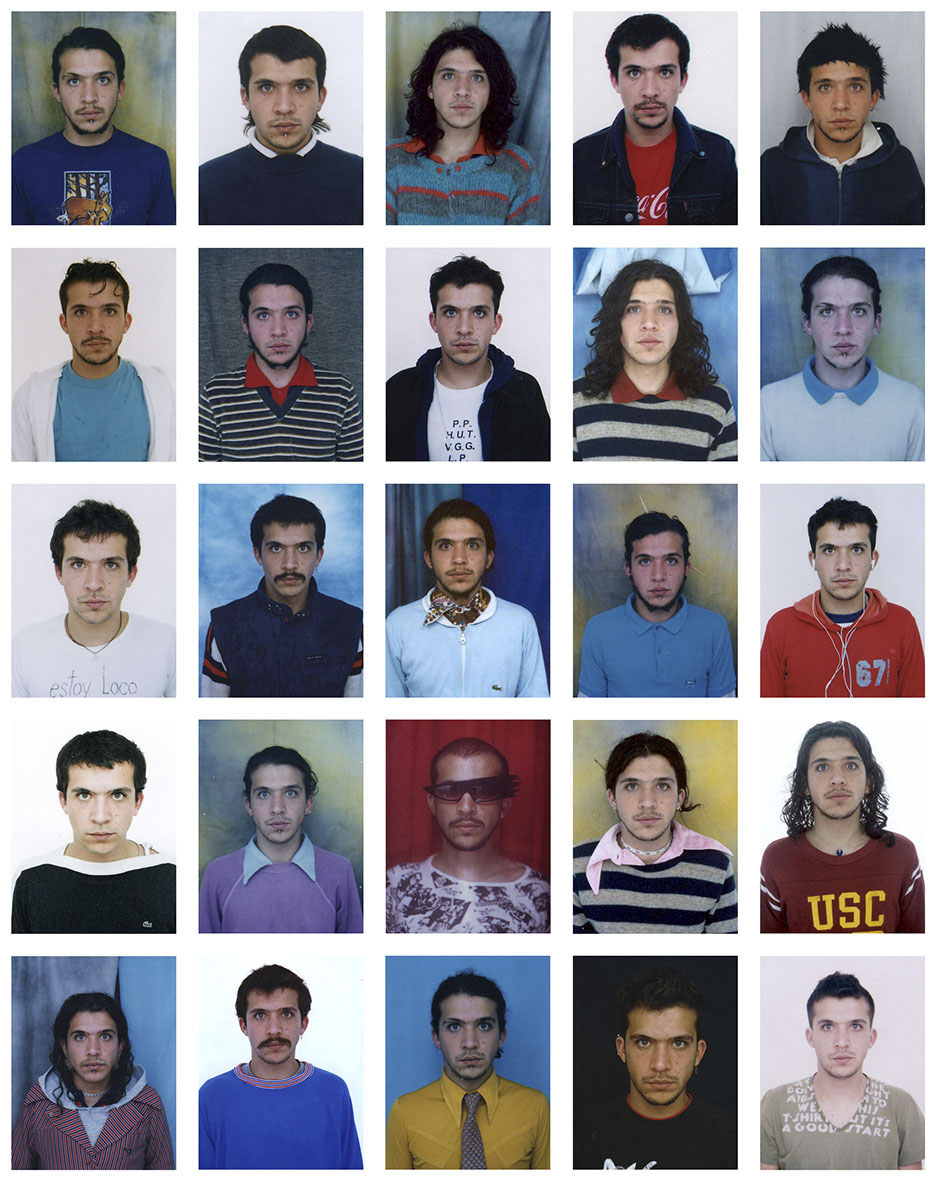

miss fotojapon (1m x 1m #4) 1998-2022

A political edge

“The technique sounds simple but then it’s executed for 20 years, and it accumulates such value, such a richness,” says Tillmans. “Some of them are full of character, some were obviously just part of his routine. In some he played, he put on the same jacket he wore 10 years ago, or 20 years ago. It is absolutely fascinating how many phases ultimately we all have. A passport photo is really a very crude approximation of our complex selves.”

Echeverri combined these autoportraits into large grids, ignoring chronology or strict typology in search of more complex investigation of the way photography and identity intersect. These grids have taken various forms over the years, but three of them are on show at extra-large size at Between Bridges – each one measuring one metre square and including 400 portraits of the artist, 1200 images in total.

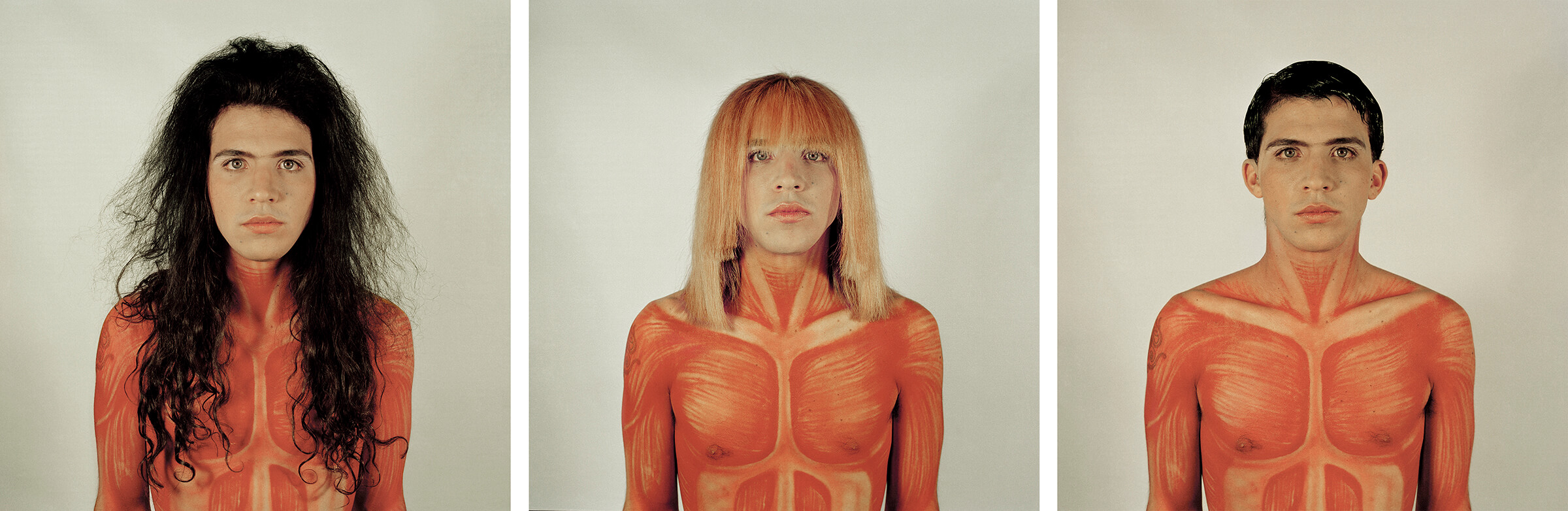

The title Identidad Perdida is lifted from a handwritten note Echeverri taped to his studio wall, and it serves as an insight into his oeuvre. As Tillmans points out, Echeverri “really never had any other subject matter than dress or taking on roles played by himself”, but that manifested in multiple ways, and took on a political edge. The exhibition includes a series of images titled MUTILady (2003), for example, documenting a performance in which Echeverri, airbrushed with an anatomical painting of the muscles beneath the skin, was photographed multiple times while a hairdresser cut and recut his hair.

On the one hand it’s a playful comment on hairstyles and subculture but on the other it cuts deeper, the title merging ‘lady’ with ‘motilar’ [‘to crop’], ‘mutation’ and ‘mutilation’, at a time when Colombians faced intense violence from paramilitary groups. “This work didn’t take place in a safe society,” comments Tillmans. “It came out of a society that was in a state of war, which is difficult [to understand] for Europeans, for anybody who hasn’t lived in a state of instability and threat.

“All this expression with identity in public came at personal risk,” he adds. “The freedom that he chose to express was, I think, a direct response to the restriction of the time in Colombia. [These works] are about everyday observations of society at large, but at the same time they have a South American or Latin American detail and tone. I think they have the most to do with authority.”

“All this expression with identity in public came at personal risk”

As Tillmans adds, Echeverri was also exploring gay identity in a strongly Catholic society, and that added another layer of complexity to his work. futuroSEXtraños (2016) shows him acting out profile pictures found on gay dating apps, for example, which were silhouetted because their owners felt unable to show their faces. MascuLady (2006) mimics the street signs popular with barbershops in the Americas, meanwhile, displaying a set menu of looks from which customers can select. And a series of music videos, Around the World in 80 Gays (2007–15), shows Echeverri lip-synching to a variety of pop songs.

Shot in various countries, these pop-pastiches suggest knowing or not knowing the social conventions, and the politics of following an example – or going off-script, or even refusing an order. “They are hilarious and at the same time uncomfortably close,” says Tillmans. “They jump from a Tokyo subway, or a Mexican wedding, or whatever city seen as the background, with all the cultural misunderstandings that can happen with such a superficial immersion.”

Echeverri’s work shows an acute sensitivity to photography and its social uses, from the ID-photos suggested by passport booths, to the rise of online posturing; he was fascinated by developments in communication, says Tillmans, and by the increasing penetration of visual culture, and consumer culture, into our lives (while simultaneously “in love with Hello Kitty, Mickey Mouse, all the rest of it, with a deep understanding of the absurdity and tragedy of it all”). And that’s key because, while Identidad Perdida is a stand-alone show, it’s also part of an ongoing programme at Between Bridges titled THESES ON HOPE.

MascuLady (2006)

“They are hilarious and at the same time uncomfortably close”

MUTILady, 2003 / 2023

Following Cuban scholar José Esteban Muñoz’s work Cruising Utopia (2009), and encompassing artists from a wide range of practices, this programme explores “minority and disidentificatory performance in their world-making capacity”; the idea is to look at art’s “anticipatory potential”, and at artists’ ability to create potential futures, in response to devastating presents. It’s an interesting framework for Echeverri’s work, because these themes seem so relevant to it and yet photography appears such a difficult medium with which to explore them, I suggest, a medium literally focused on the present moment. Tillmans both agrees and disagrees.

“Personally, as an artist working primarily with photography, I speak about the present,” he says. “I think the most we can do is sharpen our senses to understand the now. But the future is created out of the here and now. We constantly disregard the fact that the future is being forged right now – what happens today has consequences tomorrow. When we think about history, we always think of it as something bigger that happens somehow in a different mechanism, we zoom forward in time. But there are individual daily steps that cause our liberation, or catastrophe, or whatever.

“So hopefully by sharpening my senses, by drawing attention to markers of how time inscribes itself into our world, by reading the surface of the world and becoming more literate in reading the world, I hope to contribute to being able to read the future,” he continues. “I hope to be more aware and alert, not necessarily in an alarmed way, in an excited way.”

Juan Pablo Echeverri: Identidad Perdida is at Between Bridges, Berlin, until 29 July, and at James Fuentes, New York, from 7 June until 29 July