© David Moore

Moore’s pictures of Midlands housing estates pioneered kitchen sink realism in colour. Revisiting them is a chance for archival control and new representation, he tells Louise Benson

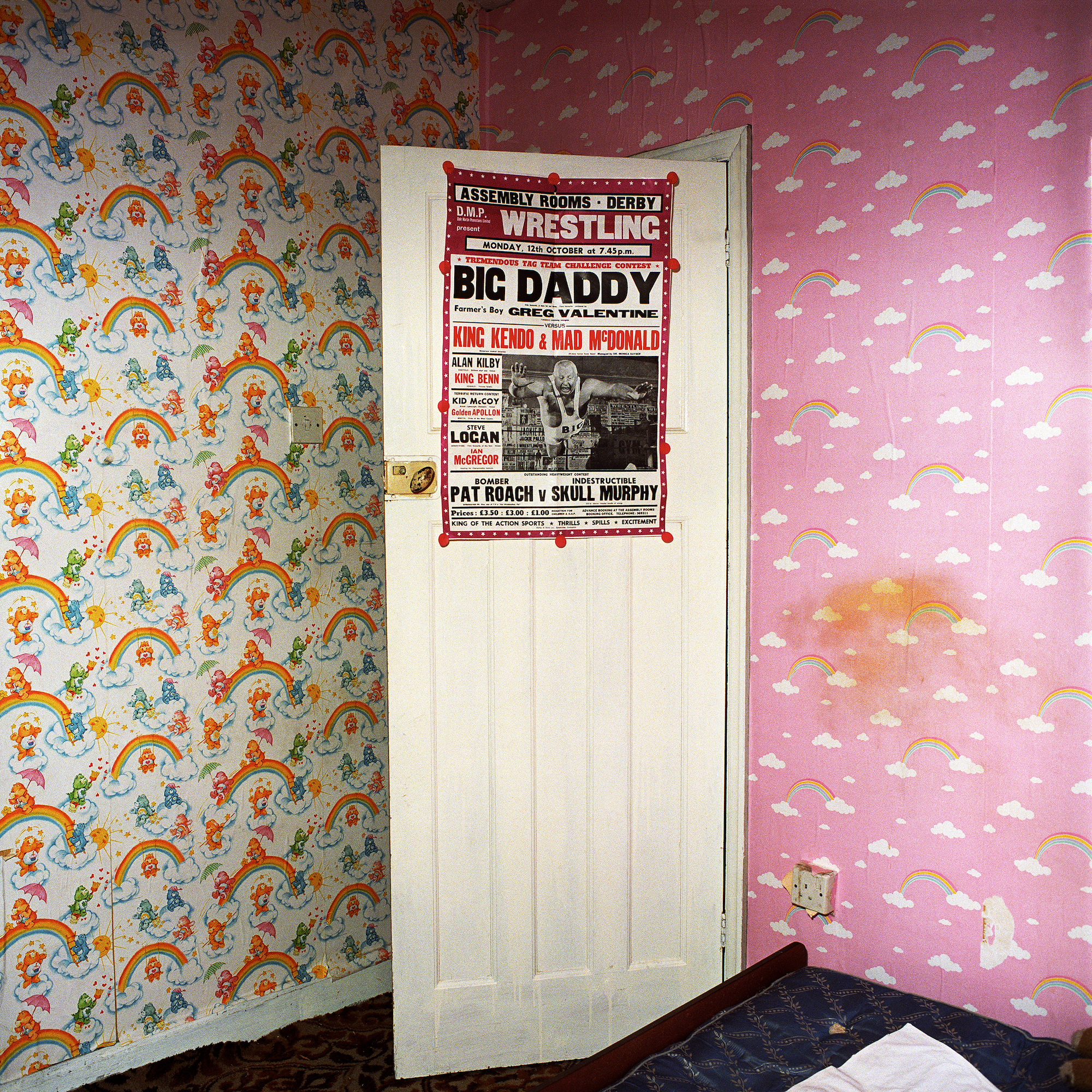

The first thing that hits you in David Moore’s Pictures from the Real World is the colours. Vivid blues, oranges and greens accentuated by the heavy flash that bounces off his subjects, inviting us into the homes of strangers. Could there be clues to their lives found in these furnishings and decorations, in the heavy cotton curtains and scratches on the wall?

It was during Moore’s time as a student in the 1980s that he first visited the Derby social housing estate where these pictures were taken, and the resulting series became his final year project at West Surrey College of Art and Design. It was to prove influential in the development of British colour photography of domestic interiors and family life, and is a project that Moore has since revisited in an unusual collaboration with his subjects.

Moore has long built a career as a documentarian of English life, scratching at its edges to reveal what might otherwise stay out of sight. He has an eye not only for stories from the margins, but for how they are told – questioning where they begin and end. He frames his images with as much of a view to what they omit as to what they contain. A hand holding a lit cigarette pushes into the edge of a shot, or the arm of a chair appears, hinting at what lies beyond. “There are endless narratives that are excluded,” he says. “Each photograph can only look in one direction.”

With Pictures from the Real World, Moore set out to make a documentary series that addressed issues of social inequity in an area that was familiar to him. He grew up in Derby in the Midlands and worked for a period for the DHSS (Department of Health and Social Services), where he would visit nearby social housing like that which he later encountered when working on the series. In both occupations, he found himself knocking on the doors of strangers. When it came to photographing this project, “I got a lot of rejections from people but I persisted,” he admits.

It was 1985 when Moore first entered West Surrey College as a photography student, a period when the miners’ strikes were regularly in the news. He was taught by the likes of Paul Graham, Martin Parr and Jo Spence, British photographers who had each made a name for themselves with their own distinctive approaches to documenting the nation under Thatcherism. “It was a thrilling time to study photography,” Moore recalls. “There was a lot of excitement about colour photography. Documentary practice was in a place of excitement and tension all at the same time, and there was a lot of synergy between different methods of addressing societal issues.”

Pictures from the Real World reflected Moore’s growing interest in aligning his political and social observations in a creative form. “It wasn’t about making great photographs at that time. It was social curiosity as much as anything else,” he says. “I hoped to make a contribution to that genre.” He worked with the five families who invited him in, documenting them and their homes over a period of months. “I learnt about families doing their best, really like any other, with their ups and downs.”

“These pictures were made during an economic recession,” Moore explains. They were shot on a housing estate which many former workers from the nearby Derby Rolls Royce aero-engine plant called home. While the factory had moved out of town, it signified the wider deindustrialisation that was taking place across the north of England at the time. As a child, Moore remembers encountering a series of late-18th century Joseph Wright paintings in Derby Museum. These atmospheric images of flames and planetary models depict the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, reflecting a growing fascination with the possibilities of the machine. “I found these works very affecting,” Moore remarks. “And I think that there’s a sure connection between them and the work I would later make in the late 90’s around past industry.”

“Documentary practice borrows from cinema and fine art, and obviously all artists absorb what is around them”

In 2017, over 30 years after he first took the photographs in Pictures from the Real World, Moore returned to the same site and invited Lisa and John, a couple who had appeared in these images all those years ago, to reflect upon and readdress the pictures from their own perspective. The resulting conversations became The Lisa and John Slideshow, a 40-minute fictionalised play performed in London and Belfast in 2018. “The play is an attempt at revision, at renegotiating some sort of equitable representation for the subjects within the image, asserting their control over the archives of the work.”

“My house had cherry wallpaper in the kitchen…” Lisa reflects in the script, much of which is taken verbatim from the pair’s conversations with Moore. They also question the character of the photographer himself, and at one point Lisa declares: “David said he’d bring us the prints but he never did.” For Moore, this process of looking through the images with them enabled him to reanimate – and rewrite – photographs that were otherwise fixed and frozen in time. “[The play] admits that every document is a blend of fiction and fact,” he says. “Using words instead of images, Lisa and John were able to speak of things outside of the photograph, filling in those gaps, and shifting the context of the same photographs.”

The images that appear in Pictures from the Real World are unmistakably English, with their particular assembly of wallpaper, posters, birthday cards, and even the light switches and door handles fulfilling familiar eighties visual tropes. Does Moore see the series as being shaped by his own national identity? “Of course, but contemporary documentary practice has taken on various visual influences for years,” he says. “It borrows from cinema and fine art, and obviously all artists absorb what is around them. I try to make everything that I do as authentic as it can be to my own observations, regardless of what is going on unconsciously.”

It is a perspective that pervades another early series, completed the year before Moore began work on Pictures from the Real World. English Domestic Interiors compiles a study of the objects, decorations and ephemera encountered by Moore in the homes of close family, relatives and friends’ parents. “With the phrase ‘English Domestic Interiors’, I’m acknowledging a difference, perhaps, in some vernacular that may have disappeared,” Moore considers, before laughing: “I could have even called it ‘English Interiors of the East Midlands,’ which would have been taking it even further, but again it’s an attempt at authenticity.”

The households captured here represent a departure from the scenes shown in Pictures from the Real World. “They’re from a slightly different set of domestic circumstances, and they reflect much more my own background than do the interiors drawn from Pictures from the Real World in terms of social class,” he explains. China ornaments and glassware are highlighted by Moore’s flashbulb, sat primly on dark wooden dressers against floral wallpaper and fringed lampshades. “I remember going to my grandparents’ homes and being so fascinated by what was on display,” he says. “It was an exploratory reorientation for myself using places that are quite familiar to me.”

Moore describes English Domestic Interiors as a still life project. Objects sit alone in rooms empty of their owners, hinting at who might occupy these spaces without ever revealing them. “I was looking at how environments can offer metaphor and simile for society,” Moore says. This attunement, not only to our immediate surroundings, but how they are shaped by broader circumstances, runs throughout his work. His skill lies in burrowing below the surface to reveal the intricate networks that connect us geographically, socially, economically and politically, like uncovering the inner workings of an electronic toy.

This is rarely straightforward, and Moore continues to interrogate his own work and the stories he is telling. “People often feel that they need to take a conventional narrative form with documentary photography, and that can be restrictive,” he concludes. “Photography is much more interesting when it asks questions rather than tries to resolve a story.”

This article originally appeared in Scenic Views Issue 4, out now

David Moore’s work is featured in The English at Home: 20th Century Photographs from the Hyman Collection at the Centre for British Photography, London, until 28 May

David Moore, Connecting Works 1986-1994, is at Sion and Moore, London, until 27 May