from the series Sun Dog © Ezio D’Agostino. All images courtesy the artist

This article first appeared in the Money+Power issue of British Journal of Photography. Sign up for an 1854 subscription to receive the magazine directly to your door.

Fascinated by the scientific and mythical implications of nuclear fusion experiments, D’Agostino traversed into the depths of ITER, the world’s largest power plant dedicated to harnessing solar energy. The result is a compelling portrait of one of the most expensive engineering experiments in human history.

Sandwiched between the national parks of Verdon and Luberon, about an hour’s drive north of Marseille, France, is the hulking home of ITER: the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor. Inside the plant’s sprawling facilities, a team of scientists from 35 nations pursue one of the most ambitious and complicated energy projects ever seen. The goal is to replicate a process that occurs naturally on the sun – whereby hydrogen nuclei collide and fuse into heavier helium atoms, releasing tremendous amounts of energy in the process. Should a stable means to harness the power of nuclear fusion emerge, a potential solution to our desperate energy needs could be on the horizon.

The experiment’s premise is “the Holy Grail for parts of the scientific community,” explains Ezio D’Agostino. “There’s very little toxic waste involved, and the required supply of hydrogen isotopes is potentially endless.” The Italian artist, who lives in nearby city Aix-en-Provence, has been photographing the site since 2019. D’Agostino’s personal work has already explored era-defining scientific questions. His NEOs project, published by Skinnerboox in 2019, pondered the moral and geopolitical implications of the looming asteroid mining industry. His work at ITER in fact stemmed from a creative commission by a Russian cybersecurity company, Kaspersky. A few years into the project, the Russian invasion of Ukraine dissolved the commission’s cross-border framework. But D’Agostino continued to research independently: “I’d already fallen down the black hole,” he laughs.

Interestingly, the ITER project itself appears immune to the twists and turns of contemporary geopolitics, however grave recent developments appear. Where sanctions are imposed and diplomatic ties unravel beyond the facility’s fences, international collaboration goes on unabated within, with Russian scientists working shoulder to shoulder with European and North American colleagues. The conventions of the outside world are here suspended, owing to the optimistic climate in which the project was dreamed up. Born in the 1980s from a delicate dialogue between US President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, ITER was “one of the first initiatives to establish cooperation between the East and the West,” D’Agostino states. It surely owes as much to money. Co-funded by the EU and six further member states, the project has generated jobs and constitutes big business for contractors. With so much already invested, to stop now would be unthinkable. By some estimates, the project’s initial budget of €6bn is thought to have multiplied tenfold – beset by a familiar catalogue of delays and technical problems.

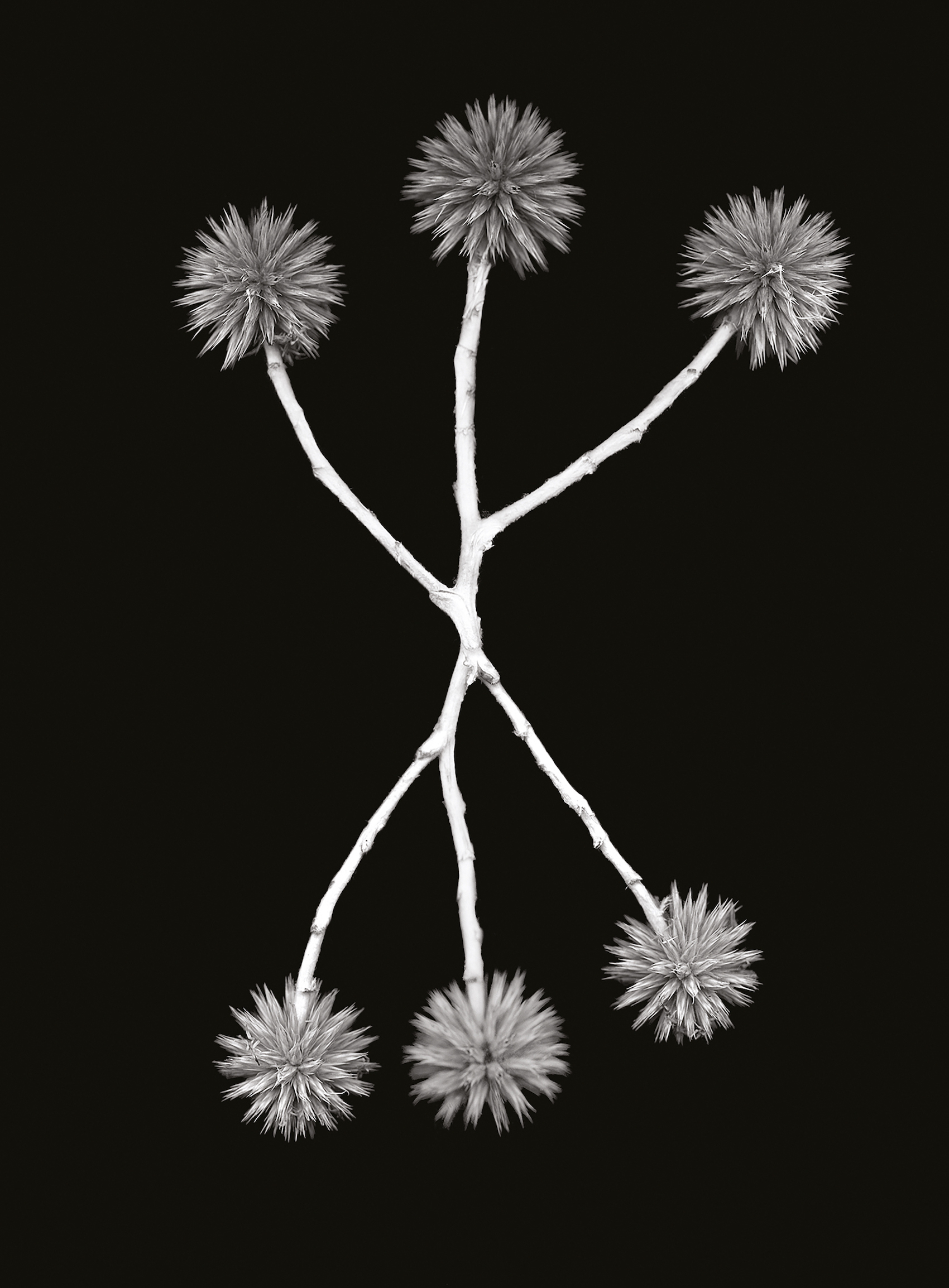

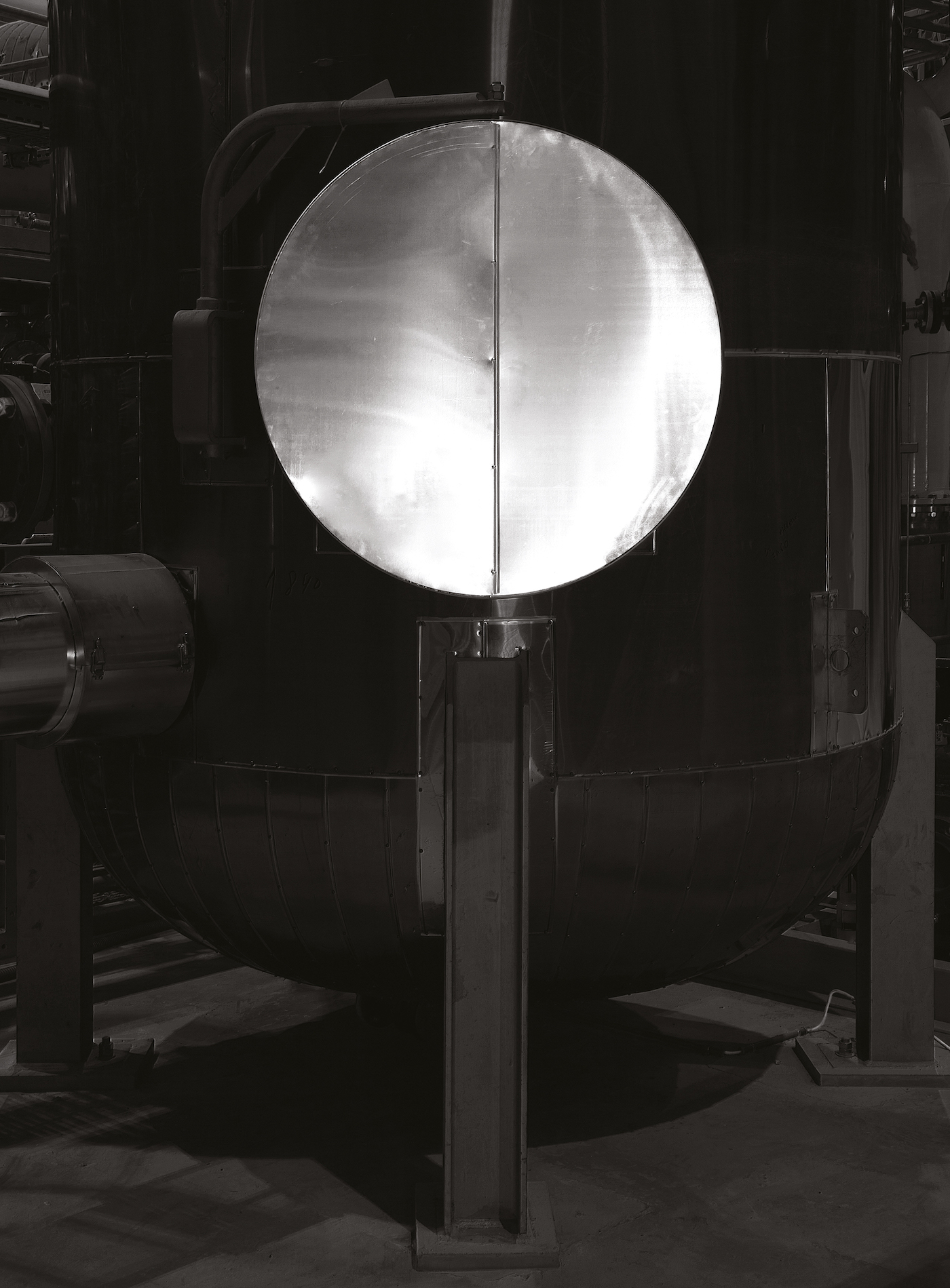

The preliminary results of D’Agostino’s explorations at ITER, where he is granted considerable behind-the scenes access, come together in a new body of work titled Sun Dog. Beyond probing at ITER’s political context, Sun Dog posits a further series of overlapping perspectives as to how we might think about the site. At times, the artist’s lens is almost archaeological – a discipline he studied before turning to photography. Through a photographic archive of architectural impressions and found objects from across the site, there’s a sense that these isolated details – deprived of their original contexts – might well have been exhumed in some future excavation campaign. In particular images, D’Agostino nods to the site’s contrasting temporalities, spanning the ancient stone on which it was built to the shorter lifespan of its man-made facilities, which are scheduled for disassembly in the 2060s.

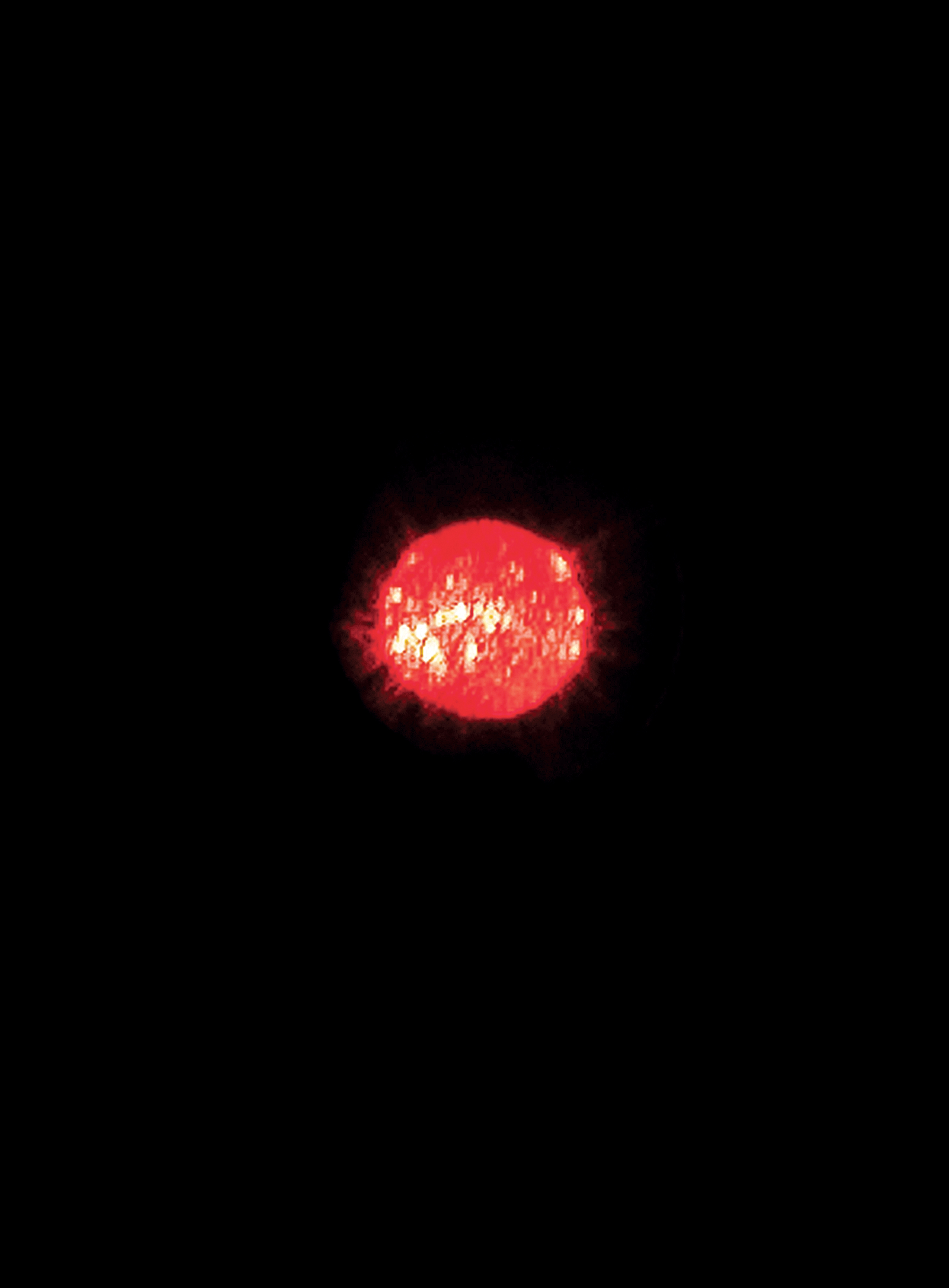

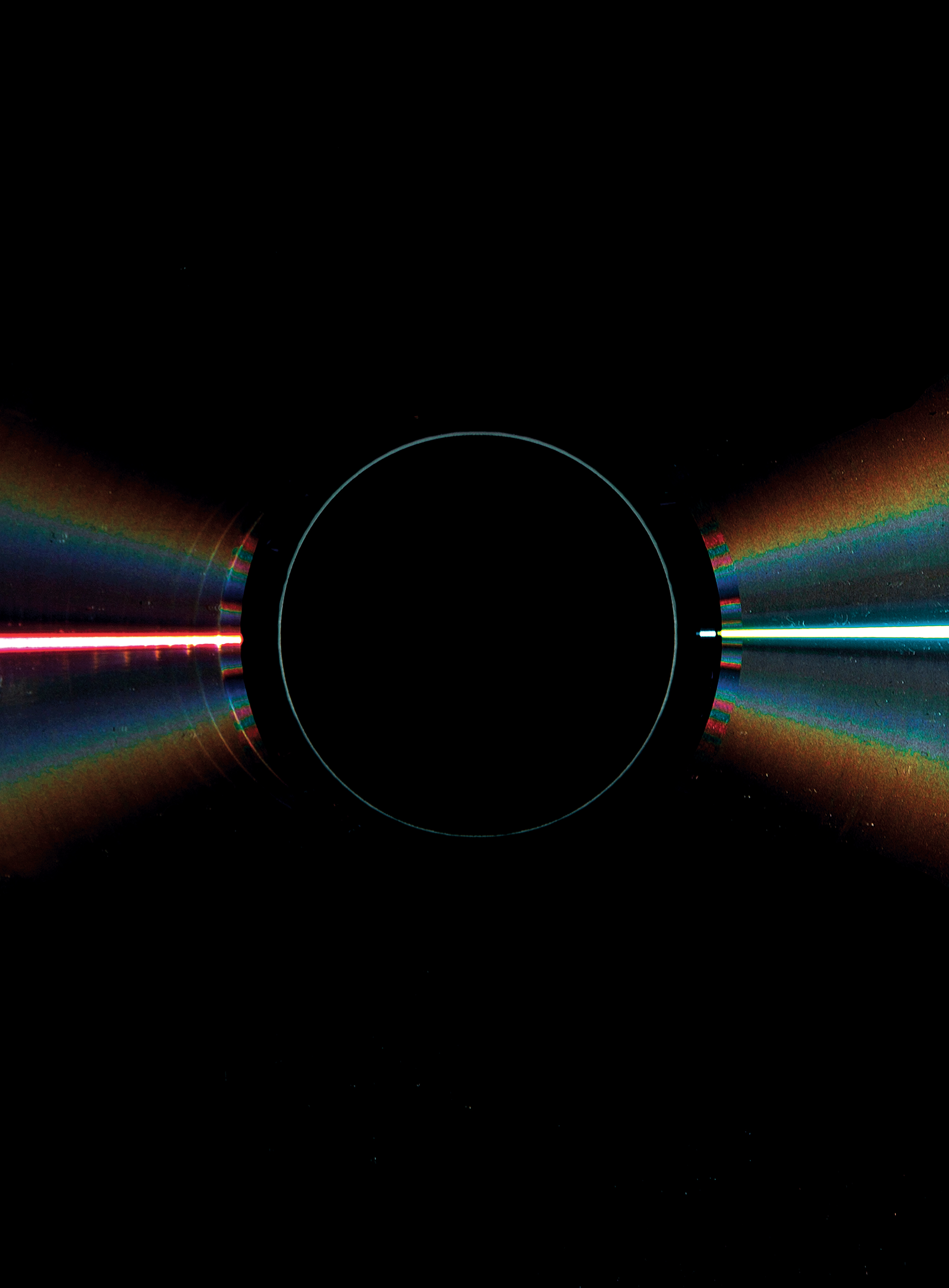

In other instances, D’Agostino’s approach is distinctly pseudoscientific. In meteorology, the term ‘sun dog’ refers to an atmospheric optical phenomenon, in which a bright spot appears on one or both sides of the sun. ITER’s primary objective is to create a kind of second sun on Earth. In an attempt to emulate this, D’Agostino runs a series of DIY studio experiments. One such “visual study of the wavelengths of sunlight” is in fact a cropped image of a CD, its surfaces glistening a colourful spectrum. These playful efforts to create a ‘real’ image of the sun are a reminder of limitations, the camera’s and otherwise. How can we recreate something we can barely even look at – an ’unwatchable star’? D’Agostino’s photo-based trials become a metaphor for the pitfalls of the wider ITER experiment, which some scientists have condemned to near-certain failure.

“Notions of time, life and death are linked to the apparition of the sun in almost every human civilisation. So, when you speak about power, [the sun is] one of the most patriarchal images we have.”

The project’s images are clinical, abstract and futuristic. Wrought largely in cold black-and-white, but punctuated by glimpses of colour, they echo the polished, otherworldly surfaces of a dystopian sci-fi movie. When set alongside other images, each photograph takes on equal weight and status; it is hard to gauge the scale or function of the scenes we are met with. They are devoid of obvious meaning, especially for the scientifically uninitiated. D’Agostino enjoys this cryptic puzzle, which is enhanced by his use of captions. The artist showed the images to a physicist, who then described their contents.

In doing so, D’Agostino abdicates responsibility for ascribing each with meaning. While this game offers answers to the images’ many mysteries, it also begs questions: What makes the scientist’s appraisal of the image more pertinent than its author’s categorisations? And, more broadly, why do we maintain blind faith in scientific thought, without ever really probing it?

When D’Agostino moves around ITER, the images he produces are rarely rooted in nuclear know-how. It is precisely his status as an outsider that opens the door to new interpretations of the site. He often describes it in religious or spiritual terms – as akin to visiting a cathedral, or “the construction of a solar temple”. “Notions of time, life and death are linked to the apparition of the sun in almost every human civilisation,” he explains, “so when you speak about power, [the sun is] one of the most patriarchal images we have.” Religious undertones are enhanced by the ritualistic choreography of his visits to the reactor, requiring a precise uniform and the symbolic act of foot-washing before entry. He recalls a succession of the plant’s giant doors opening incredibly slowly, as well as the darkness and sacred silence of the place. “It’s so enormous that when you’re there with your camera, trying to evoke ITER in one image is impossible,” he explains. “That’s why I work in fragments; to put together some pieces and leave the viewer to reconstruct the puzzle.”

Might ITER, though, become another case of Icarus flying too close to the sun? In D’Agostino’s reflections, an acknowledgement of human hubris is inevitable. That this is merely an experiment is crucial; the trials will yield no energy, and the project has no planned commercial output. It is instead thought of as a vital in-between step – or to critics, the most costly science experiment in human history.

The artist, though, is more measured, opting to observe first and judge later. “I don’t know if I’m critical per se. I’m a photographer, not a scientist. I know my place! But the money put into the ITER project could surely solve a lot of our energy problems. While there isn’t any kind of public discussion about it, I just want to pose some questions.”