Photography by Megan Dalton.

This article is printed in the latest issue of British Journal of Photography: Performance. Sign up for an 1854 subscription to receive it at your door.

Inside a converted tractor shed with a tin roof, overlooking the moors of West Yorkshire, Yan Wang Preston connects to nature and embraces her roots

It is a blustery winter’s day in Todmorden, West Yorkshire. Still, it is mild for January, and the sun’s rays percolate through the clouds onto the purply green moorland below. As we wind up the hill towards her studio, Yan Wang Preston points here and there. “I’ve made work over that hill,” she says. “And around those black rocks there.” The taxi stops just before the concrete of the road gives way to holes and puddles, and we walk the rest of the way. On our approach to the large sandstone house, we are welcomed by the deep bark of a black Labrador called Marley. We sweep past, towards the tin-roof building next door: a converted tractor shed that is Preston’s studio.

Entering through a side door, a yeasty musk fills our nostrils. It is coming from the firewood that Preston collected the previous day, which was repurposed from whisky barrels. Through the short corridor, we enter the main space. It is warm from the burning stove, and light floods the room. A glass facade stretching the entire length of the building reveals an uninterrupted view across the valley. It is magnificent. “It’s a very close connection between me and the outside world,” says Preston. “I can see very far away to the windmills, I can hear the wind. And when it rains, it’s really loud. Then, I don’t listen to music because that is the music.” Right on cue, a rainbow beams across the vista.

Preston resides here with her husband and eight-year-old daughter. “It reminds me of the place I lived when I was a child, my daughter’s age,” says Preston, who was raised in China. “It was a very small town with a small river and small hills. I walked to school and, on my way, I’d collect butterflies, dragonflies and plants. I feel almost like I’m home, even though I’m here.”

The family moved to Todmorden four years ago, but Preston has been living in north England for nearly two decades. She was born in Henan Province to a family of doctors. Following in their footsteps, she gained a BA in clinical medicine at Fudan University, Shanghai, in 1999 and qualified as an anaesthetist soon after. It was in 2005 that she packed it all in to pursue photography, and moved to the UK. Since then, Preston has developed a research-led practice through which she explores nature and landscape to investigate cultural and national identity, migration and societal relations. Her first major project, Mother River (2010–2014) traced the Yangtze River to its source, photographing the surrounding environment at 100-metre intervals on a large format camera to gain an intimate understanding of contemporary China. For Forest (2010–2017), Preston investigated the journeys of ancient trees as they were uprooted and transplanted into urban environments, and the complexities behind that industry. In 2020, her focus turned to the UK. For one year, she walked to the same rhododendron bush in the south Pennines every other day. Preston became fascinated by the idea that the plant is a non-native, invasive species. She uses it as a metaphor to discuss post-colonialism and identity, giving it the title With Love. From an Invader (2020–2021).

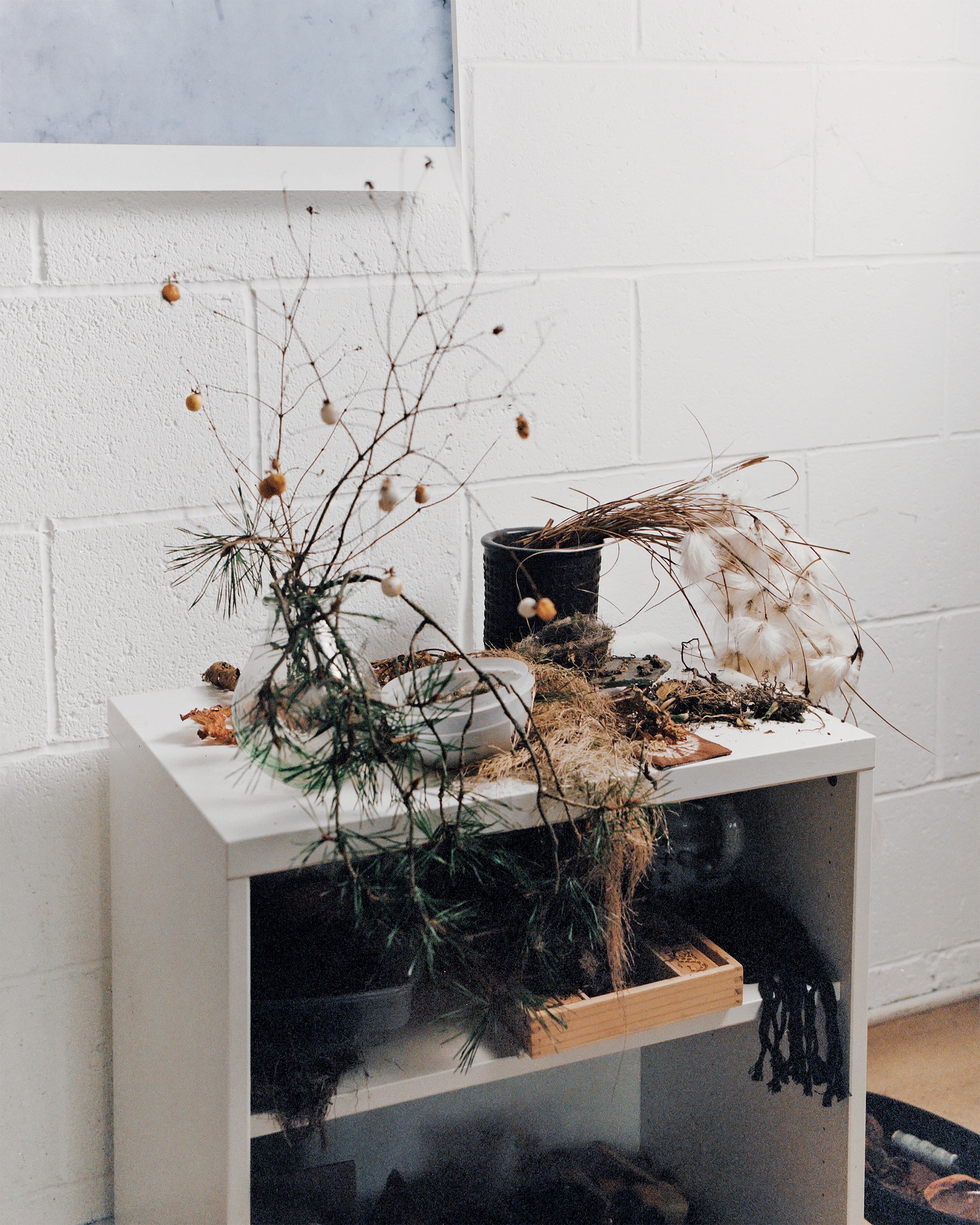

Selected prints from these past works decorate Preston’s studio walls. In the corner, two boxfuls of dusty pink stones, polished by the Yangtze River in Chongqing, remind her of her journey so far. The studio also houses Preston’s newest “collections”. Just as she did when she was a little girl, Preston fervently gathers anything that might inspire a future project. My eye darts around the space. There is a box of dried rhododendron petals; another filled with sheep’s wool gathered from surrounding fields. There is also a crate of fluffy white cotton. She plucks a tuft from each box and rolls the fibres in her hands. “I’m not sure what I’m going to do with these yet,” she remarks. Sculptural tree branches rest on the table at the back, next to a shelf stacked with grasses and dried plants. Some of these are arranged on another table under two studio lights, where Preston has been experimenting with still life. “Working with organic materials is exciting because you have to go with them or they just go off,” she says. “There’s only so much planning you can do, and I like the intuitive side of things.” Outside is a pile of tree trunks and a tangle of witch hazel cut from the garden. There is even an empty bird’s nest on the counter by the sink and a crumpled pile of metallic blue and pink balloons. “I drag things in…” she says.

“I started by cutting the world open, I ended up cutting myself open… Cutting myself open really means to become self-aware.”

Preston’s process has evolved from strict, self-imposed parameters to a much deeper intention to connect with nature, where she lets the subject lead. “Nature has always been there, but what I’m doing now is closer to botanical studies, with art and nature together,” she says.

The compulsive habit of collecting materials from the environment, and working with them in her studio, is key for her ongoing project, Autumn, Winter, Spring and Summer. For Autumn, Preston gathered the fallen leaves of a rhododendron bush, arranged them in neat formation and photographed them in sections. They are layered and printed in Shanghai on a six-metre-long silk scroll. Preston wears white gloves as she unpacks it from a fine, embroidered, green silk box with traditional Chinese clasps. As we unroll it, handling it slowly and delicately, like the wing of a butterfly, we move through a medley of browns, maroons, burnt oranges and lime greens. The fine silk is almost translucent.

There is also a book, a hefty tome. The cover brandishes a tiny glass capsule housing a single rhododendron flower bud. “They are aborted flower buds,” Preston explains. She found 75 in total, and photographed each one as she opened them. I leaf through the life-sized prints. At the end, a sentence reads: “I started by cutting the world open, I ended up cutting myself open.” After dedicating so much time to the pieces, picking, ruminating, picturing and printing, alone with her thoughts, the work became somewhat cathartic. ”Cutting myself open really means to become self-aware,” says Preston. “[I gained an understanding of] the reality that we live in; that yes, I can be a strong woman, but I’m still in a system.”

“I’m trained here [in the UK] as an artist, but my medical training is coming through too. It’s the first time I’ve embraced myself. It’s taken so long.”

This time last year, Preston worked on Winter. She gathered the rhododendron seedlings from a smaller bush and arranged them in a circle on the wintry ground. She set them on fire then photographed them in large format. The images capture a near-spiritual moment as the flames danced around the snow. It was ultimately an experiment – “the snow came again and half buried the seeds. It finished [the piece] for me,” says Preston, gazing at the series of 12 images taped to a section of the studio wall. “I learned so much from this. Opening up, working with nature rather than on it. The performative side of my work has always been there, but it was suppressed. Now it’s completely out, that’s the way I like to work.”

One particular work dominates the room. A human-sized image of a pile of crinkled petals collected over three months from a smaller rhododendron bush. They are arranged in a slim oval shape, in colours that oscillate between amber, maroon and pink. The paper is cut down the middle and sutured together, like surgical stitching, with black thread. “It scares me because it’s so violent,” Preston says. “This is the piece that is most challenging for me. I’ve done so many tests on different materials.” Speaking of Autumn, Winter, Spring and Summer, to which this last piece also belongs, Preston muses that this is her first “mature” body of work. “It’s the first piece where I am really bringing back my Chinese heritage,” she says. “It started with the long scroll. Then the shape of the fire – the circle within a square – is a very traditional Chinese composition. Then I started working with the suture stitch. I’m trained here [in the UK] as an artist, but my medical training is coming through too. It’s the first time I’ve embraced myself. It’s taken so long.”

Preston offers us scones and we drink builder’s tea under a picture of the late Queen. Opposite, postcard-sized traditional Chinese drawings and yellow Post-it notes adorned with English and Chinese scribbles are stuck to the pillar. Preston is also working on a project with the working title of English Garden, exploring the concept of a garden that is full of non-English flowers; more “non-native invasive species,” she says. Her face is animated as she describes her plans; she is brimming with ideas for future projects that will take her back to China for the first time since before the pandemic. Embracing her heritage, her identity and her past, Preston is heading into the year open and aware.